April 18: What, and who, makes a great photographers’ gallery?

April 18: What, and who, makes a great photographers’ gallery?

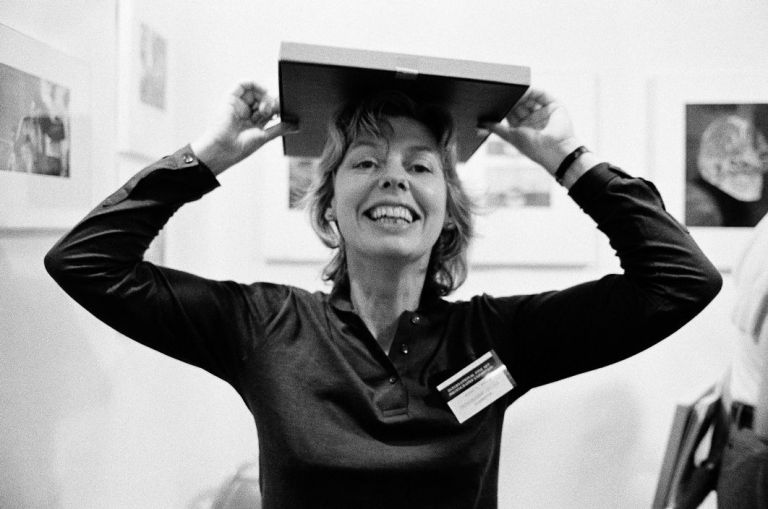

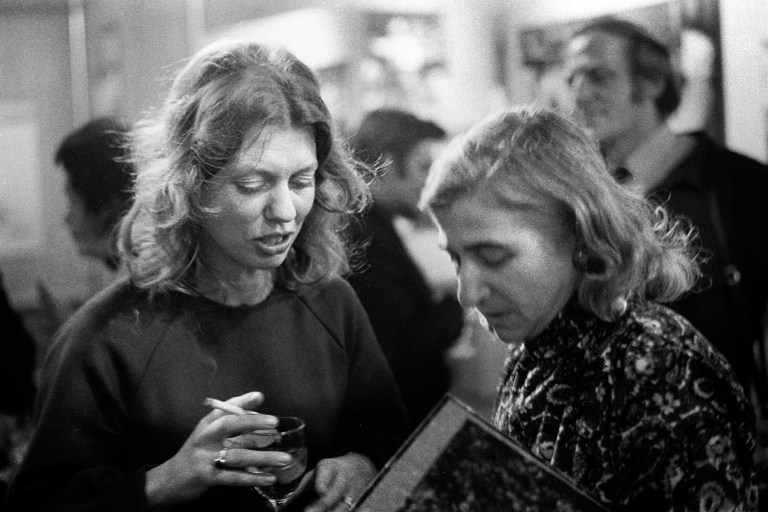

I’ve just started a Wikipedia biography of Sue Davies (*1933, April 14) who died today after a long illness, ending a story that strikes me as notable in the annals of our medium; her founding of The Photographers Gallery in London on 14 January 1971 was an act of courage, backed by the re-mortgage of her own house in which she lived with her husband the jazz musician John R. T. Davies, and their three daughters.

The UK, with its long history dating to the origins of the medium, was reluctant after WW2 to revive its recognition of photography as art, or at least as worthy of exhibition in a dedicated gallery; there were none! The United States, postwar, already had galleries which showed photography exclusively by the 1950s, including another started by a courageous woman, Helen Gee, in 1954, and by the 1970s had a thriving scene, particularly in New York, and had a photography department in the Museum of Modern Art founded by Beaumont Newhall in 1940.

The effect of this was felt in a flood of American work appearing in, and being purchased by, galleries around the world; a corresponding impression amongst world photographers and students of photography that they should look to the USA for inspiration and legitimisation; and a resultant American monopoly of the medium that lasted into the 1990s.

In Australia, this was most clearly an influence on our Photographers Gallery in Prahran (related only in name to Sue Davies’ establishment) whose American-born director Bill Heimerman, between 1976 and 1978, showed in order of appearance, Paul Caponigro, Brett Weston, Wynn Bullock, Boone Morrison, Aaron Siskind, William Clift, Ralph Gibson, Emmet Gowin, Ralph Gibson colour work, Jerry Uelsmann, Harry Callahan, Robert Cumming and Eliot Porter.

Australian woman curator Jennie Boddington, inaugural director of the photography department at the newly (1968) re-housed National Gallery of Victoria; Alison Carroll and Ian North of the Art Gallery of South Australia (which had begun to collect photography as a distinct discipline from the mid-1920’s, its building expanded in 1962, refurbished 1979); and David Moore and Wes Stacey at the Australian Centre for Photography (est. 1973); all purchased from Heimerman’s Photographers’ Gallery, with special interest in American and European works. It was these sales of US photography, in contrast to the Australian works marketed for much less, that contributed significantly to the standing and survival of our Australian Photographers Gallery, particularly in its early years of the 1970s and 1980s.

The later-established Church Street Photographic Centre was opened by Joyce Evans in 1976 as a specialist photography gallery and bookshop, the third commercial photographic gallery in 1970s Melbourne to open after Brummels (1972) and The Photographers Gallery (1973). Evans also showcased, and competed with Heimerman to sell to the same public institutions, international photography, mostly Americans including Berenice Abbott, Imogen Cunningham, Elliott Erwitt, Robert Frank, Les Krims, Martin Lacis, James Newberry, Arnold Newman, Bill Owens, W. Eugene Smith, Alfred Stieglitz, Paul Strand, Jerry Uelsmann, Brett Weston, and Minor White, along with Australian works which again fetched lower prices.

England’s 1970s was a dismal period set between Harold Wilson’s ‘swinging sixties’ and Margaret Thatcher’s socially divisive eighties, though optimistic for women. Germaine Greer’s Female Eunuch (1970), the publishing house ‘Virago’, Jill Tweedie and others on the Guardian’s Women’s Page gave vent to female dissent and desire for a more adventurous way of life, with more women entering universities and colleges and their working conditions improving under the Labour government’s 1970 Equal Pay Act and Sex Discrimination Act (1975), with the Domestic Violence and Matrimonial Proceedings Act of 1976 promising women greater protection against violent partners, while divorces increased.

Against an economic background of increasing austerity, The Photographers’ Gallery was decidedly not-for-profit and Davies registered it as a charity. As such, it could largely set its own agenda, but still had to pay the rent and cover costs, which it did partly through admissions of an audience of 20,000 in its first year. Fortunately support for British photography came from Arts Council when Barry Lane was appointed their first photography officer in 1973 and increased access to financial support for photographic initiatives.

Nevertheless, prior to that, alongside valiant efforts to raise money, such as Sue’s Rent Party! Raise the Roof to Raise the Rent! in February 1972, compromises had to be made to get by. Initial exhibitions showcased American, not British, photographers; The Concerned Photographer curated (with many of the images dating back to The Family of Man), by Cornell Capa featured his brother Robert Capa, who like him had migrated to the US, Fortune photographer Dan Weiner, Leonard Freed and Lewis Hine, while their fellow exhibitors David (Chim) Seymour and Werner Bischoff both worked for LIFE; and that was followed by an Edward Weston show before English practitioners started to feature, and mainly in themed, rather than solo, shows.

An exception was David Hamilton who featured in three shows, the touring exhibition and book Vier Meister der Erotischen Fotografie (‘Four Masters of Erotic Photography’), originating from Cologne’s Photokina in 1970, Dreams of Young Girls in December 1971, and The Sisters & La Danse at the end of 1973. The nakedness of this emperor of photography, who later committed suicide after being accused by one of his models of raping her at age 13, was exposed in a review by the critic and photojournalist Euan Duff (*1939) who wrote in The Guardian in 1973:

In the area all around the Photographers’ Gallery are shops where you can buy explicit and inartistic photographs of teenage girls in sexual situations. Inside the gallery David Hamilton provides us with large colour photographs of teenage girls in sexual situations: the difference lies in their gross sentimentality. The models look to be between 13 and 17 years old and some are seen half clothed in open legged positions with their genitals only just covered, whilst others touch and caress each other. The lesbian overtones are strong; the photographs use the most cliché pictorial symbolism, exploiting soft focus, pastel colours, country landscapes and old houses, old fashioned clothes and even white doves to give a phoney impression of health-food ad naturalness; they are a sort of wholemeal stoneground pornography. They are also very popular, maybe because they don’t provoke guilt the way dirty pictures do. But they are artistically dishonest because they show girls who appear to be innocently preoccupied with themselves, but who are in fact models in contrived situations exhibiting themselves to titillate voyeur interest in the sexuality of immature girls.

Duff’s response is consistent with own work which was earnestly socialist; photojournalism in which he documented How We Are (the title of his 1971 book) and the Workless (his 1975 book). Critic John Berger wrote of How We Are:

“I can think of no comparable contemporary English work of literature or visual art which so gently, so persistently and so finally brings one face-to-face with the wretchedness of the kind of society in which we live: a society in which every personal meaning achieved by an individual is pitted against corporate meaninglessness; in which every personal need, expressed in terms of what is socially available, is in agonizing conflict with the origins of that need in the soul.”

Though he never exhibited at The Photographers’ Gallery, Duff’s work is more typical of what was happening in British photography of the era, though there is a sense that in the early shows there, Davies was casting around for a sense of what that was, while at the same time showing what would bring funding; exhibitions then are remarkably more wide ranging and inclusive in their content than shows there today and included The Financial Times Industrial Photographic Awards; J. H. Lartigue: Photos from 1909 till Today; 37 Sepia Prints of John Thompson’s Street Life in London, 1870; An Olivetti Exhibition: On the Many Uses of Photography in their Industry; Scoop, Scandal and Strife: A History of Newspaper Photography, to list a sample of 1971 exhibitions, shows which reflect expedience and the interests of the Gallery’s directors.

An exhibition of young photographers followed in April, all men, with a mix of colour still life and B&W street photography à la Tony Ray-Jones, but its names, Mark Edwards, Meira Hand, Roger Birt, Sylvester Jacobs, Tim Stevens, Bob Mazzer and Mark Trompeteler, apart from Norman Parkinson, are now unfamiliar.

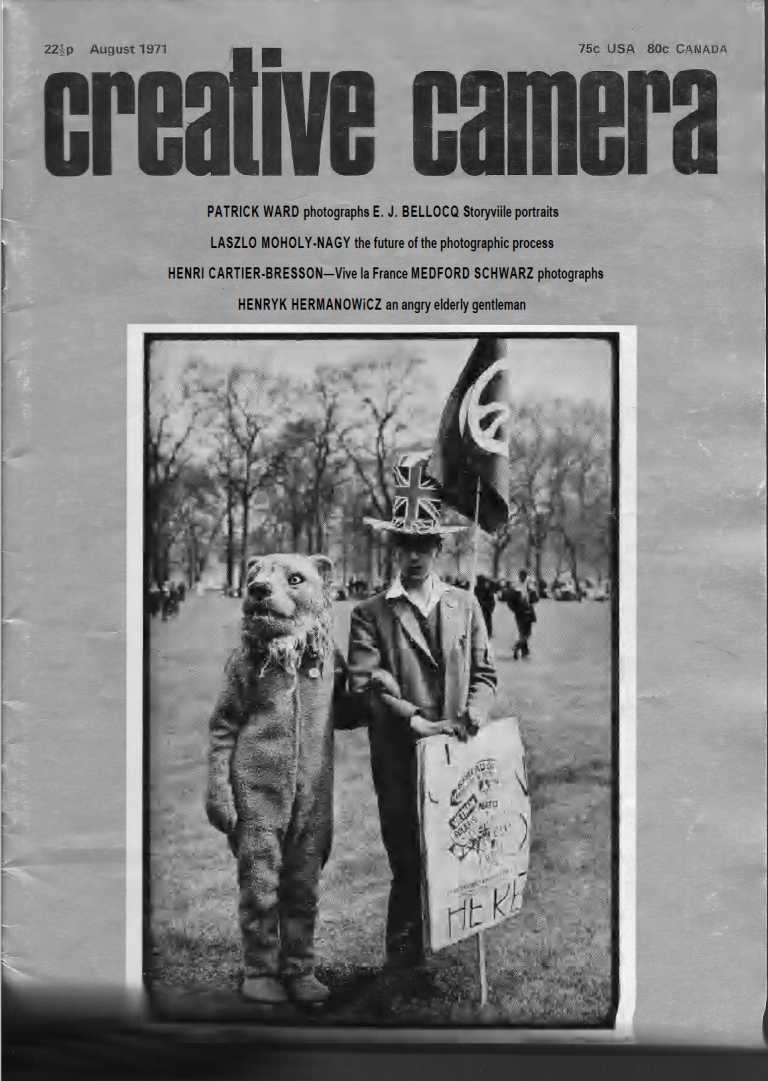

Duff’s How We Are was a feature in the October 1971 edition of Creative Camera, which earlier reviewed The Concerned Photographer at The Photographers’ Gallery. The magazine expressed no confusion about what constituted significant photography, and had done since Bill Jay became editor in November 1964 of its earlier incarnation as Camera Owner, and courted an audience of more serious photographers. Whether they were practitioners of fine art or documentary, whether British, American or European, historical or contemporary, the names on its pages are still well known in photo-history, even though it too suffered financially — editorials throughout the early seventies regularly plead with its readers to subscribe or to pay their subscriptions on time.

The list of all those featured in Creative Camera through 1971, the year the Gallery opened, reads like a ‘Who’s Who’ of the era: Keith Jacobson, Tony Ray-Jones, Ken Graves, Brett Weston, David Hockney, Susan Carver, Michael McQueen, The Concerned Photographer, David Leigh-Smith, Linda Connor, David Hurn on the Arts Council Exhibition, Bruce Davidson, Alan F. Blumenthal, Geoff Howard, Don McCullin, Ron McCormick, John Miles, Ulf Sjostedt, Wynn Bullock, Derek Boshier, Larry Herman, Jacques Henri Lartigue, Mark Edwards, Paul Martin, Imogen Cunningham, Margaret Harker, Christine Pearcey, Patrick Ward, E. J. Bellocq, Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Medford Schwarz, Henryk Hermanowic, Lee Friediander, John Benton-Harris, Helmut Gernsheim on Hill and Adamson, Howard Selina, Ruth Bernhard, Marketa Luskacova, Andrew Lanyon, Ralph Gibson, Richard Kalvar, Guy Borremans, Robert Demachy, Bert Hardy, Homer Sykes, Philip Sayer, Daniel Kaufman.

That said, though the audience overlapped, the economies of scale in running the Gallery were definitively different than if publishing a magazine, and by 1973 The Photographers Gallery has defined itself, its audience and its exhibitors. In 1977 The Guardian‘s Alex Hamilton did a profile on Sue Davies and noted that the cost of running the Gallery then was £57,000 with £26,000 coming from the Arts Council, and the rest made up in book sales and commissions on 500 print sales over the previous 18 months. Still, even by 1978, when the News-Journal of Mansfield, Ohio surveyed the photography scene in the UK, it concluded that “for the English, art equals painting,” and that “even the Tate draws an uneasy distinction between photography produced by photographers and that produced by artists, and only collects the latter,” but that The Photographers’ Gallery nevertheless was drawing big attendance numbers, all due to a woman who, as The Observer put it, “worked like a demon….[and…as a result it is now perfectly possible that she has founded, single-handed, what may become the photographic equivalent of the National Gallery.” She was a hard act to follow.

However, even as early as 1994, when Davies’ (less ‘legendary’) successor had left after two years and its board members were falling into opposing camps or resigning, its continuation was being called into question. The Barbican was then showing the huge Val Williams curated Who’s Looking at the Family? a distinctly British response to Peter Galassi’s Pleasures and Terrors of Domestic Comfort (MoMA 1991) incorporating a greater European perspective and extending the range of photographic genres, particularly “Outsider” and “Found Photography”.

As (American) David Levinthal‘s cowboys hung on the Photographers’ Gallery walls, in a Guardian article Mike Ellison asked prominent commentators in the discipline “The Photographers’ Gallery was set up in the seventies to promote photography as an art… But is that still necessary?” to which an unnamed ‘former employee’ answered that everyone wanted it to be all things to all people, with no real idea of what photography was all about. Frances Hodgson (formerly manager of the Gallery’s Print Room, but who in 1994 ran Zwemmer Fine Photographs, a Dutch fine art publisher) was more forthright;

“The Photographers Gallery has done what it set out to do, to stimulate an interest in the art form. Now every college has a photography course, galleries exist and flourish. Why not shut it down? It’s a moribund institution.”

John Stathatos editor and founder of Untitled: A review of contemporary art and shortlisted for the director role after Davies retired, remarked;

“When Sue Davies started it, there was nowhere else. Now some members of the board have reached the Zimmer frame stage, though any institution is going to fossilise after a decade without change”

The deputy director Ian Jindal pointed to the artists showing at The New Contemporaries; “..more than half of them were using photographic practices without calling themselves photographers.”

Martin Parr added;

“The wider issue is to do with the status of photography in this country. We are a beleaguered minority and now we’ve started to squabble amongst ourselves”

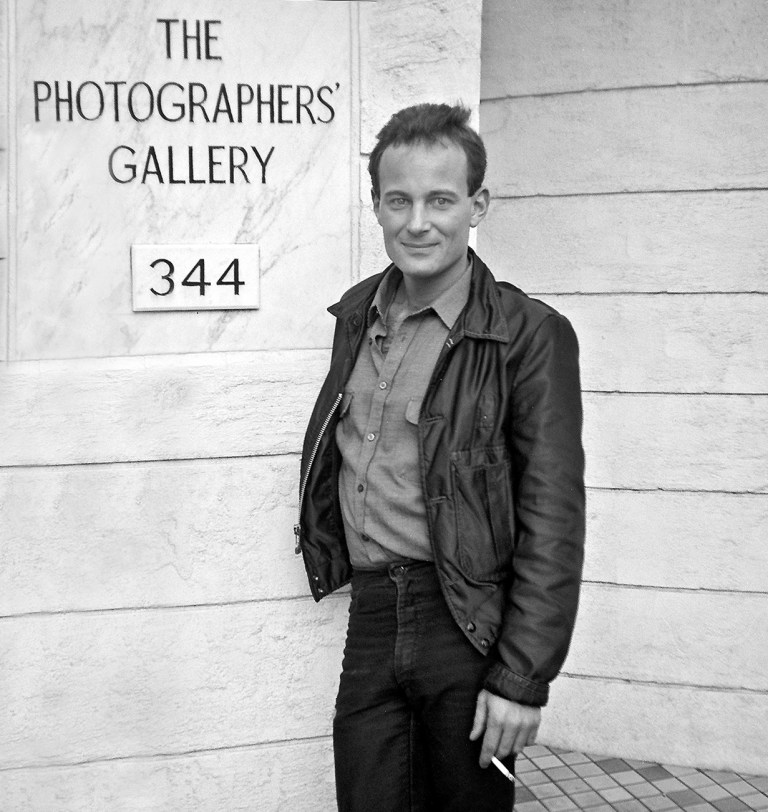

The Photographers’ Gallery however survives. In May 2012 it moved to a an architect-designed venue in Ramillies Street, in the heart of the West end and at the gateway to Soho housed over three floors of exhibition space, education studio for events, talks, courses and learning activities and retaining its café and bookshop.

Before the full story of Sue Davies and the phenomenon she started is lost, it has to be drawn out from those remaining who knew her, so that a legendary example of success can be preserved.

Thanks for this fabulous account James –

Hoping this finds you well, the evidence suggests you are coping well! For myself I’m up to my neck juggling work video conferencing and home schooling…

Best wishes

Daniel

Professor Daniel Palmer

Associate Dean, Research and Innovation

School of Art

RMIT University

Building 24, Level 2, Room 1A

124 La Trobe Street Melbourne VIC 3000

E: daniel.palmer@rmit.edu.au

T: +61 3 9925 4769

RMIT University acknowledges the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin Nations as the traditional owners of the land on which the University stands, and respectfully recognises Elders both past and present.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Daniel for taking time to comment so kindly…I can see professors, tertiary lecturers and secondary teachers having huge demands made of them, and so are parents, who might now appreciate how hard teachers work! For me, the physical isolation is habitual, by choice, so I’m experiencing no big difference, while others are truly suffering…awful for those who have lost work! I visited The Photographers Gallery twice, once in 1991 when Sue herself looked at my photos, and again in 2012 (to find it not yet reopened)…what a remarkable example was Sue Davies…no doubt she made mistakes, but had the guts to start something big against some not inconsiderable resistance!

LikeLike

Thanks for this James – I took many groups of students to TPG between 1995 and 2017 – there was always something useful (and often controversial) for the students to take away. I hope it survives this year and continues for many more decades – we’ll perhaps see how valued photography actually is in Britain if it does.

LikeLiked by 1 person