December 14: Context

Did museums cause the shift to a new understanding of photography as art in the 1960s and 1970s?

Did museums cause the shift to a new understanding of photography as art in the 1960s and 1970s?

Most of Australia’s state libraries and museums had, and have, photographic imagery held for its historic, educative value, such as the Melbourne Public Library’s Pictures Collection (of paintings, drawings, prints, cartoons, photographs and sculpture) started in 1859. But it was not until the late 1960s that museums in Australia began to see photography as collectible art.

The first was the National Gallery of Victoria. Its Department of Photography had been established in April 1967 and was run part-time by photographers, including fashion photographer Athol Shmith, photojournalist Les Gray and Chairman, advertising photographer Dacre Stubbs, who along with sculptor Lenton Parr, then Head of Art and Design at Prahran College, oversaw the purchase of the photography collection’s first work, Australian photojournalist David Moore‘s 1948 Surrey Hills street (purchased through the Kodak (Australasia) Pty Ltd Fund) and in 1971 the acquisition of their first international work František Drtikol‘s Nude (1939), mounted the Gallery’s first solo photographer’s exhibition by Mark Strizic in 1968 and acquired prints by 21-year-old photographer Carol Jerrems; her Alphabet assignment for her Prahran College lecturer Athol Shmith!

In 1972 Jennie Boddington was appointed its Curator (as ‘Assistant Curator’ to the Director Eric Westbrook), and two years later the Art Gallery of New South Wales followed suit with the appointment of Gael Newton, but the National Gallery of Australia was not to have a Curator of Photography until New Zealand-born photographer Ian North was appointed in 1980 when its building was finished.

To choose Boddington as curator was remarkable; she was a filmmaker, not a photographer nor a photo historian, identified in a 1984 Metro Magazine interview by Rosa Safransky as “one of the few women to make a living as a documentary filmmaker in Australia since the Second World War”. That was quite an achievement; though women directed and produced commercial feature (fiction) films throughout the silent and early sound periods in Australia, there was a decline in women’s participation after that due to reduced production of Australian films generally (very few Australian feature films produced 1940s–1969) and the increasing preference by the public for Hollywood productions. The local industry did not return to health until the 1970s, when most Australian features were funded by the Australian Film Commission (established 1975) and its state government counterparts, and in the 1980s when private financing increased with Division 10BA (1981) of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 allowing investors a 150% tax concession on their investment at risk.

The rescue had come too late for Boddington, who after marrying early and having a son, had entered the industry by first writing film reviews then via a job as a wardrobe assistant in the 1940s. She then trained and worked in the Commonwealth Film Unit. After her divorce in 1950 she made her own way for six years scripting, editing and directing training films for the GPO and, after the advent of television in Australia, with the ABC, before marrying cinematographer Adrian Boddington and having three more children, working under her maiden name Blackwood to produce 15 films, several of which were AFI prizewinners.

They were documentaries with subjects ranging from telephone services through the eyes of a schoolboy doing a school project; to apples for export; the story of three of the million migrants into Australia after the end of the war; Anzac, pioneering in its use of the rostrum camera; a film on the taboo subject of breast cancer, innovative in being presented as a soap opera; another on the Port of Melbourne; a bio of Sir John Monash; and others.

In 1967, Boddington decided to retire from the partnership to spend more time with her children, who before had to be looked after by domestic help, and planned to work on a novel, but her husband died in 1970. To support her three children, she moved back to Sydney where she found only part time work so returned to Melbourne.

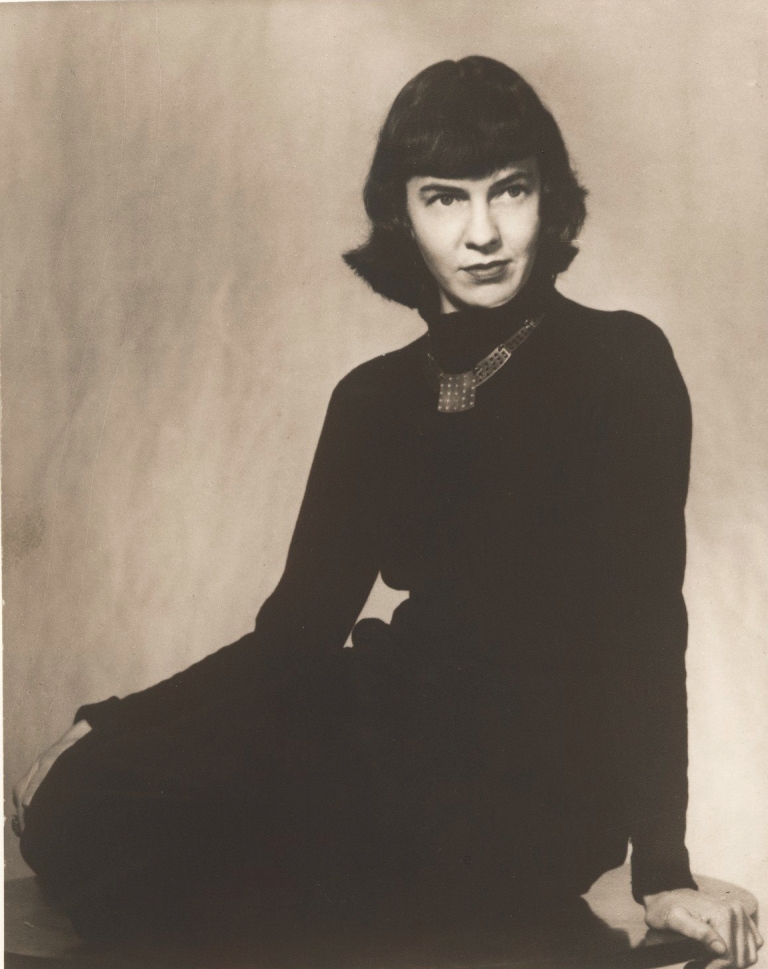

A friend was Erwin Rado, a member of the Melbourne Film Society in 1952 when he took the portrait (above) of Jennie. Was it his recommendation as the festival’s first paid director that caused her to apply, and helped her get the job? Whatever the reasons behind her selection for the position from 53 applicants (as noted in the Minutes of the NGV Photographic Subcommittee of May 16, 1972), when others such as Gael Newton might have been more qualified, Boddington did bring with her an admiration for the documentary image, and a scriptwriter’s pragmatic ability to research and write.

As I’ve noted in the biography I wrote for Wikipedia, Boddington proved quite astute in her choice of shows for the teething NGV photography department. Her selections were not restricted only to ‘art’ photography but were inclusive of that which was of value as a medium of communication.

Historical context is needed to understand what Boddington faced as a newcomer to the scene. Lindsey Stewart writing in Hannavay’s Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Photography notes that in 1968 interest in historical photography as a collectible was only just emerging, and that it wasn’t until 1971 that Sothebys had started holding regular auctions of them. In her thesis Writing photographic history in Australia : towards a critical account, Anne-Marie Willis (currently Professor at German University in Cairo) identifies this dilemma for any curator who would challenge the orthodox Beaumont Newhall-style photo history limited to images that are distinctively photographic, aesthetic, and “Straight”; she would open a Pandora’s box full of photographs pervasive across so many fields, of such limitless subject matters, and crossing so many disciplines that their histories in photography would be obscured. The concern was that photography, newly crossing the threshold of the museum, was in danger of being limited by a high art interest to form and print quality. That she was aware of this is evident in Boddington’s 27 February 1975 letter to the of the Australian Centre for Photography (est. 1973) complaining to its inaugural Director Graham Howe (appointed January, 1974) that ACP’s first major exhibition had “an element of speciousness…it is self-conscious to an unfortunate degree of its “Art” content, and this is death to the vitality of photography.”

To start with Boddington devoted several exhibitions to contemporary Australian photographers, well known and the recently discovered, giving equal billing to male and female artists; among whom were Micky Allan, Jon Rhodes, Carol Jerrems, Jillian Gibb, Ruth Maddison, Anthony Green, Merryle Johnson and David Stephenson. Her debut of Geelong landscape photographer Laurie Wilson was overblown, but her recognition in 1975 of the Prahran student Bill Henson with a solo, his first, Of Tender Years, was prescient.

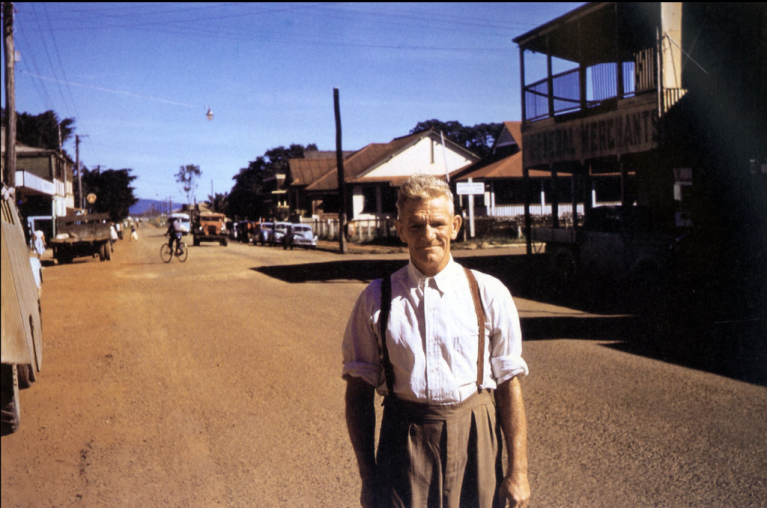

She included early Australian photography in the program and when his descendants brought Fred Kruger‘s prints and glass plates to her she not only gave them wall space in 1983 but wrote a catalogue that still stands as an authority on an important pioneer. Others on whom she wrote catalogue essays included J.W. Lindt, Herbert Ponting and Russell Hurley. When she discovered Russell Drysdale‘s use of colour photography as an aide-mémoire, in her 1987 book she reveals Drysdale’s expressive stylisation in interpretation of colour, subject matter and specific locations was derived from the previously unknown photographic imagery.

In 1974, John Szarkowski, Curator of Photography at the Museum of Modern Art in New York visited Australia, supported by a grant from our Visual Arts Board, to consult with the first Executive Committee of the ACP. Szarkowski’s position prioritised art photography over photojournalism, documentary, activist and conceptualist uses of the medium and, as Patrick McCaughey noted at the time, and Anne Marsh in 2010, his desire was to see art photography elevated from its realist, documentary representation of society.

When Boddington toured Europe, London and America in 1975 she of course met with Szarkowski, who influenced her decision to make acquisition of important overseas material a priority. Even her limited budget enabled the purchase of six Ralph Gibsons from his his 1977 show at Bill Heimerman‘s The Photographers Gallery, also 18 by William Clift shown there that year, five Harry Callahan works and four Robert Besanko‘s in 1978. But clearly budgetary restraints—or missed opportunity—meant that thereafter she bought only four from Franco Fontana‘s show there in 1979 while the ANG bought eight, and one each from Ian Lobb‘s and Lisette Model‘s but passing up Larry Clark, John Divola, Edouard Boubat, Emmett Gowin, Eliot Porter and William Eggleston, while the ANG and AGNSW scooped up bargains that were never to be repeated!

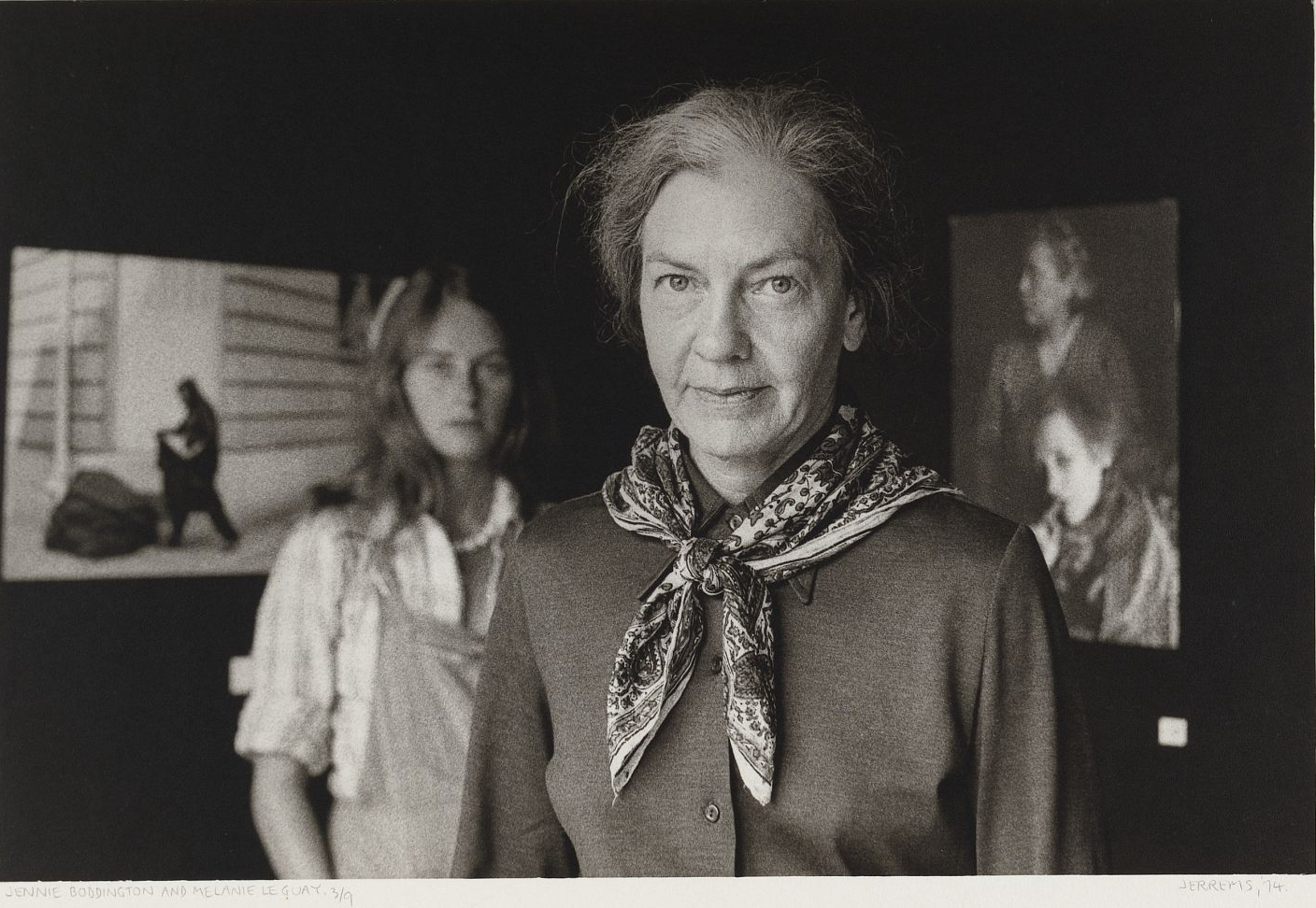

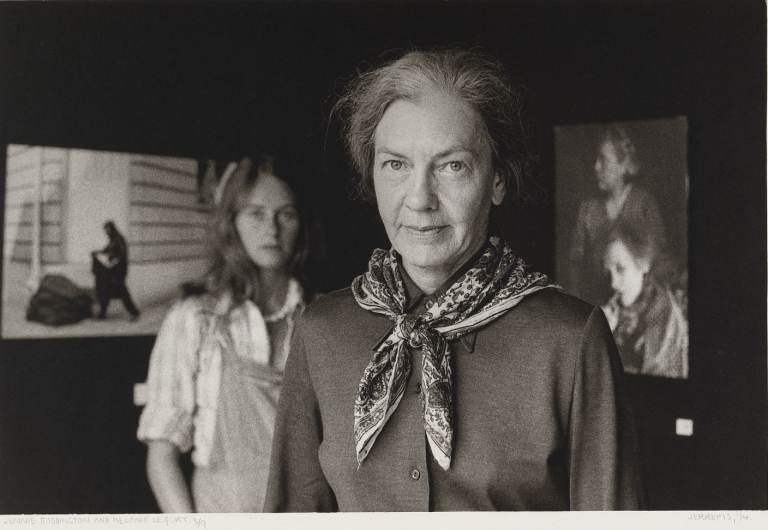

She had staged important shows of international work—at the Henri Cartier-Bresson exhibition she organised at the National Gallery of Victoria in 1974, Boddington was photographed with Melanie Le Guay by Carol Jerrems for the latter’s A Book About Australian Women which was published that year. Boddington’s indulgent, even motherly, but watchful regard is apparent in Jerrems shots from that session, which also use the Bresson images on the gallery wall as a visual commentary. The first international shows by David Goldblatt (1975) and the equally controversial Czech Jan Saudek (1977) were at the NGV, which purchased their works. All three shows are ones that I remember as being the most important that I saw in my student years.

A sense of context is important in evaluating this critical time in the course of Australian photo history and without it, it is easy to be critical of the main players such as Jennie Boddington. In her case she faced plenty of flack. I remember her visit at Athol’s invitation to Prahran College (he was still on her advisory board). Talking with students she encountered objections over her choice of the sort of photography to show (some may have been somewhat jealous at Henson’s good luck) and exacerbated it by arguing that all of us should get some industrial experience (of the kind she had) before thinking about exhibiting. But really we were all arguing the same thing—that photography in the gallery should not be restricted to what was considered ‘art’.

On meeting her on another occasion in the early ’80s at her Richmond home and sitting at her dining room table beneath an apocalyptic Peter Booth painting, one could not be unimpressed by her enthusiasm for her work and her knowledgeability, and sympathise with her resentment at the criticism she received, mostly from men.

Yes, she stayed on too long—two decades—at the NGV, but she is, amongst our other curators, in good company in that regard; there is too little circulation amongst the public galleries still. Perhaps she became complacent, tending to neglect the local scene in pursuit of international work but without the money to make it worthwhile. In evaluating Boddington and her legacy, it is worth reading what Marcus Bunyan and Toby Meagher, have to say.

Great piece, thanks James.

LikeLiked by 1 person