November 1: An archive, no matter how big, is of little use if its contents remain unidentified and undescribed.

November 1: An archive, no matter how big, is of little use if its contents remain unidentified and undescribed.

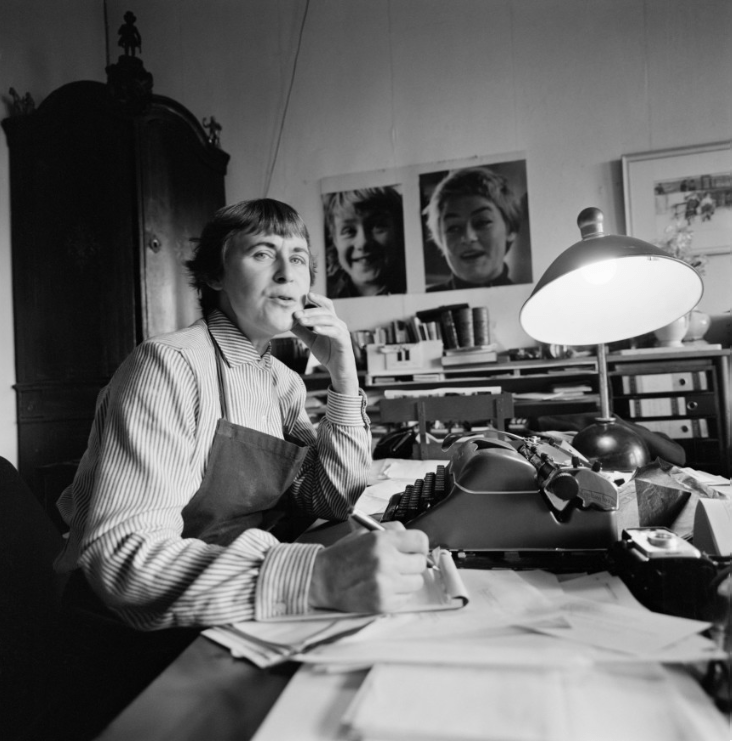

One of the Netherlands most prolific and best known photographers Casparus (Cas) Bernardus Oorthuys, was born in 1908 on this date November 1, in Leiden. He worked before WW2 producing photography and graphics for communist and anti-fascist organisations, and during the war helped forge identity papers and photographed clandestinely for the Underground Camera to document the activities of the German occupiers, and also the awful Hongerwinter, the Dutch Famine of 1944/45. During the postwar recovery he recorded the Nuremberg war crimes trials and the rebuilding of his homeland. At the end of his career he left 500,000 pictures.

His huge archive was faithfully maintained after Oorthuys’ death in 1975 by his wife Lydia who until she was in her seventies sold its imagery to a variety of clients. In December 1998 she was interviewed in the elderly citizens home into which she had just moved. She met Oorthuys in the thirties, when she was seventeen.

I was drinking a glass of wine on a terrace with my sister. Cas came along in a funny green suit. An attractive man. His bike was lumbered with tripods and lamps. He knew my sister well. She worked as a copy-editor for de Waarheid. He often helped with the layout at night. That meeting was the first. Shortly after that I asked if he could make my portrait. Then we hit it off.

In 1939 Oorthuys had divorced Sini Broerse, with whom he had two children, and married Lydia on 3 April 1940, just before the war broke out in May. She describes Oorthuys as ‘a nice man’ but very serious because he had been raised in a strict, orthodox manner by a father who was a Calvinist minister. He had turned away from religion in his youth while studying architecture in Haarlem and with his fellow student Nico de Haas he had become a long-haired member of the free-thinking Dutch Association of Abstinent Students (NBAS), but, she said, “he would lighten up after a drink”.

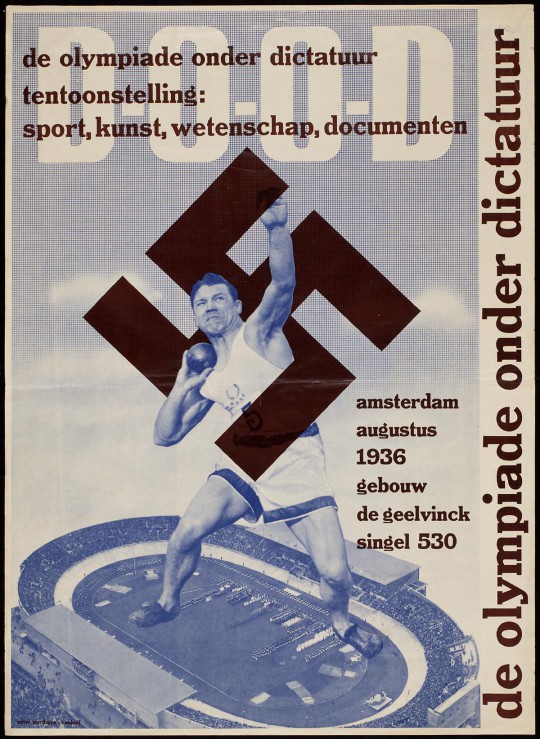

During the war Oorthuys became involved in the Personal Identification Centre established in 1942 and made passport photos for fake ID cards, while earning a meagre living on an assignment from publishing company Contact for a book about agriculture. In May 1944, when he took ration cards to the architect J.J. van der Linden and others in hiding, he was arrested by the Germans and ended up in camp Amersfoort. Unexpectedly, he was released again in August, presumably at the interposition of Nico de Haas who, despite having been with Oorthuys one of the founders in 1936 of the ‘photo and film’ group of the Association for the Defense of Cultural Law (BKVK) in preparation of the anti-fascist exhibition De Olympiade Onder Dictatuur (DOOD), had quickly worked up to become a prominent Dutch SS man after the German invasion.

On release Oorthuys connected with De Ondergedoken (‘Underground’) Camera, formed around Dolle Dinsdag on the initiative of the German emigrant Fritz Kahlenberg and the former soldier Tony van Renterghem; ‘Underground’ because the Nazi occupiers declared a complete ban on “photographing, filming, drawing, and displaying persons and things in any other way outside of domestic spaces” from November 20, 1944. The aim was initially to document the Allies’ liberation which was longer in coming than hoped, and instead they recorded a severe winter of hunger and resistance in photos that have become the image of the German occupation, especially Cas Oorthuys’ picture of a woman with a piece of bread in close-up.

A variation (above) was published on the cover of Amsterdam tijdens den hongerwinter (‘Amsterdam During the Winter of Hunger’) published by Contact / De Bezige Bij, in 1947, while the now more famous image from this series reached an audience of 9 million through the 1955 exhibition and publication The Family of Man, about which I have recently been blogging.

Polish poet Witold Wirpsza (1918—1985) describes it best, in his 1962 ‘Commentary on the Photographs’, in homage to The Family of Man;

Were the wedding band gold, she’d have sold it long ago.

Just a couple months back the nails were still well kept,

Now they’re black at the edges. The eyes are sunken,

If still open wide enough to express sadness.

A hungry person has a right to sadness. She avails herself of this right.

This woman will go and eat. She’ll eat the crust of bread and

Go on eating, more and more voraciously, doing so with the help

Of the movement of her jaws and, in swallowing, the bump in the throat;

In this manner the things (one mustn’t forget the voraciousness) will make their way from oral cavity

To stomach (ravenousness). She’ll go and eat. After eating the bread

The dirt from under her fingernails will end up in her stomach. She’ll go on

Eating.

After the war Oorthuys had maintained the left-wing convictions that had prompted his joining the worker-photographer movement Vereeniging van Arbeiders-Fotografen in 1932, and with his equally idealistic friends Carel Blazer, Eva Besnyö, and Emmy Andriesse, formed the Vereniging van Beoefenaars der Gebonden Kunsten, the GKf, on September 1, 1945.

Lydia and Oorthuys had three children, sisters Fenna and Hanna, the youngest a son, Frank, born in 1960, and photography became a family concern; during the summer holidays they traveled to make photo pocketbooks on different countries;

We went as a whole family, to the Ardennes or to the Riviera. If he had to travel alone, he left with difficulty, but once he got going he always wanted to stay there, saying: ‘If only we could start a business in Paris’. He could not make that leap, but always toyed with the thought. Oorthuys was not good with foreign language. That is also a reason why we never started living abroad. He was shy in a certain way. He admired Henri Cartier-Bresson but could not strike up the courage to visit him. In the fifties and sixties, publicity photographs by Cas were hung in the trains, which made him really famous. Then he was sometimes stopped in the street: ‘Are you Cas Oorthuys, the photographer?’

The Oorthuys archive consists of more than 550 000 negatives.

Cas was pretty businesslike. If you can think of it he had done an assignment on it…If he had a client on the phone he could hardly say no. Then he usually defensively said: “I ask a lot of money”; that didn’t matter, they wanted him anyway. Especially at the end it became too much for him. Cas also had difficulty with criticism. He was easily annoyed and always immediately in the defence […] I know how to judge photos, but I’ve always been involved with one man, with one archive. And colour, I do not like that at all. We had little money for ages. I found payment delightful. As soon as the money was in, I paid the bills; always the private ones first. When Cas saw the statements a few days later, he would say with such a sad dog look: ‘Where did the money go? You never let me be rich for a day.

Customers who came to view the archive were different, especially those who left the engine running at the door while rifling through the contact books in a way that made you feel inadequate. Others became friends for life. I had many short nights. No one ever made appointments; when they saw lights light on in the evening, they just called in. Photography was not the most important thing for Oorthuys. He would rather take a walk, looking for fun things on the Waterlooplein. He would have preferred to become an architect. He took pictures for fun, to make something beautiful. He needed to keep the archive up to date and just wanted to photograph everything. He always took too many. When twelve photographs were requested for a calendar, he made at least 300. He could never wait for anything. It was always: walking, walking, walking and just photographing. And then suddenly he would say: ‘I have it’.

Lydia was only 55 when Oorthuys died but continued working in the archive, but in her early seventies realised that most people of her age were already retired, so gave in to Flip Bool‘s continual, but gentle requests, and gave the whole collection to Nederlands Fotomuseum. She took up a disposable camera to document the renovation of the family’s dyke house in Brakel and found she too enjoyed photography.

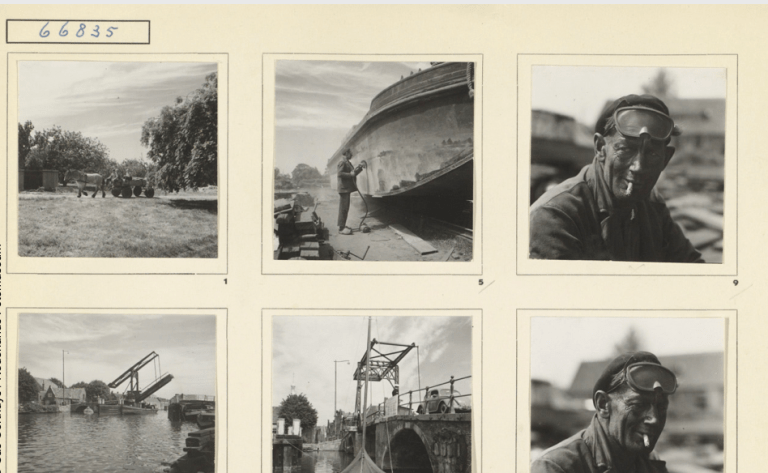

On September 15, 2018 a long-awaited major retrospective This Is Cas: Vintage Photography Cas Oorthuys opened at the Nederlands Fotomuseum. The institution is currently running a project Captions for Cas aimed at preserving, digitising and describing his archive. In 447 albums are contact prints of almost all black and white and some colour negatives and transparencies organised by topic, but need to be identified so that the entire archive can be accessed digitally by the public.

The information about the photographed subject is unfortunately minimal. Occasionally, subject and date were noted, but a description of the individual images missing. The Museum is looking for specific knowledge of certain countries, regions, cities, crafts and industry in the period 1935-1975. By signing up for the project you can share your knowledge with Captions for Cas. The archive spans an important part of the twentieth-century history doing which industries have disappeared, processes have been updated, production shifted to other countries and cities like Rotterdam radically changed, so the albums of contact sheets are a journey through time.

You can join the project (which requires a knowledge of Dutch) here.