Eva Besnyö, who died on this date in 2003, certainly figures amongst the great women of Dutch photography, but discussion of her inevitably turns to the question of whether she developed a personal ‘style’.

Eva Besnyö, who died on this date in 2003, certainly figures amongst the great women of Dutch photography, but discussion of her inevitably turns to the question of whether she developed a personal ‘style’.

That question cannot be considered without an understanding of her determination to be a photographer at a time that it was a difficult profession for a woman to enter.

Despite her enlightened upbringing in a liberal Jewish Hungarian family, she opposed her father’s wish that she enter higher education like her two sisters, one in political science and the other in German literature. Eva’s father, Bela Blumengrund, a lawyer for Hungarian feminist and women’s movements, in order to avoid anti-semitism then rife in Hungry, changed the family name to Besnyö. In about 1925 Eva is given a Kodak Brownie and she decided on a photographic career. The support of her sisters in her bid for emancipation and independence is evident in the symbolism of this shadow play between the siblings on the cobblestones of Budapest. Even so early, she conceives of an innovative image expressive of human relationships.

With her father’s gift of a new Rolleiflex she represents herself in this 1929 self-portrait in a middle-class, but not ostentatiously furnished, bedroom. And with her father’s blessing she entered the studio of photographer Jószef Pécsi (1889–1956) in Budapest. Then, just twenty years old in 1930, after participating in the Book and Advertising exhibition in the Museum for Arts and Craft with other apprentices of Pécsi and obtaining her “journeyman” certificate, Besnyö escaped the stifling fascism of Hungary, and arrived in Berlin.

There she is exposed to modernist and experimental art and photography through the artist György Kepes (1906—2001), who also migrated from Hungary that year, and fellow countryman László Moholy-Nagy (1895—1946) who had arrived ten years earlier and who collaborated with Kepes in his studio.

I came to Berlin and as the lights went on … That was actually the most important year in my life. (Eva Besnyö Interview 1991)

Her embrace of modernism and the influence of these artists is reflected in her high-angle portrait of Kepes, a near contemporary at four years older. The inclusion of the newspaper adds a collage-like element.

A comparison of street scenes captured from above by the two photographers reveals the readiness with which Besnyö adopted the Bauhaus aesthetic; she takes full advantage of abstracted silhouettes generated by the the long shadows, while Kepes’ interest is on graphic structures of the street, such as the tram lines and lamp, and his lone cyclist plays a secondary role as a point in space.

She found work as assistant to the art historian and photographer Dr Peter Weller (*1897) in the Berlin metropolis, rejoiced in its democratic lifestyle and explored its building sites to photograph workers, and the Wannsee with its swimmers.

While Besnyö was open to artistic experiments, she also made documentary images; her most famous photo from that time being that of summer 1931, made in Hungary at Lake Balaton of a young gypsy with his battered cello, which has come to be used so often since as an icon of the vagabond existence.

For a few months 1930/31 Eva worked as a volunteer with the Berlin advertising photographer René Ahrlé (1893—1976), in his studio in Nurnbergerstrase 7, before returning to Dr. Peter Weller’s Nollendorfplatz studio where this disorienting double portrait was made in a mirror on the studio floor. Usually this is presented cropped, but the inclusion of the male figure in the full frame is prophetic, as we may see now how it inverts the ‘glass ceiling’.

She rents a studio with a darkroom in Nachodstrasse 25 and at last begins business on her own as a photographer trading as Neofot and selling to the press agent Klinsky in Amsterdam.

It is at this point, at the beginning of her twenties, that Besnyö has recognised her strengths; her modernism and her abilities in documentary photography. For the rest of her career these are threads that she follows as they cross and interweave. In the words of American and close contemporary Lee Miller (1907—1977);

It seems to me that women have a bigger chance at success in photography than men… Women are quicker and more adaptable than men.

Besnyö’s stay in Berlin was cut short by a rising sense of dread with the ascent of the Nazis and increasing anti-Semitic sentiments; after a brief sojourn in Hungary with new boyfriend the cameraman John Fernhout (who married her in 1933), she made a timely escape to Amsterdam in autumn 1932. There she quickly made Dutch friends and enjoyed the support of the circle of Fernhout’s mother the painter Charley Toorop; filmmaker Joris Ivens, designer Gerrit Rietveld.

Toorop often used Besnyö’s photographs as reference, as can be confirmed in these details, and surmised from the inconsistent lighting of faces in Toorop’s De maaltijd der vrienden, above.

Besnyö actively promoted herself and held her first solo exhibition in 1933 at the renowned Kunstzaal Van Lier at the Rokin in Amsterdam established in 1927 by Carel van Lier (*1897) who was to die in the Mühlenberg concentration camp in March 1945. From that year, at 23, she was amongst the vanguard of Netherlandish photographers, with the older Piet Zwart (1885—1977) and Paul Schuitema (1897—1973), and contemporaries Cas Oorthuys (1908—1975), Carel Blazer (1911—1980) and Emmy Andriesse (1914—1953).

The years following led to few and poorly paid jobs, and her work became political due to the circumstances, however amongst these, were commissions to make architectural photographs with which she had great success because of her ability to use the New Vision to convey the idea of functionalism.

![Eva Besnyö Untitled [Summer house in Groet, North Holland. Architects Merkelbach & Karsten] 1934 18.2 x 24.2 cm Collection Iara Brusse, Amsterdam](https://onthisdateinphotography.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/eva-besnyc3b6-untitled-summer-house-in-groet-north-holland-architects-merkelbach-karsten-1934-18-2-x-24-2-cm-collection-iara-brusse-amsterdam.jpg?w=768)

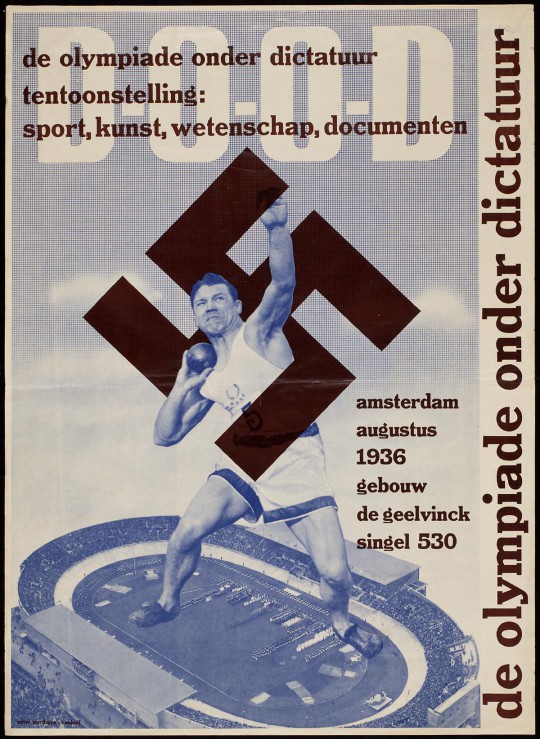

In the second half of the 1930s, Besnyö engages actively in politics, participating in 1936 in an anti-Nazi-Olympics exhibition DOOD; (i.e. ‘De onder Diktatur Olympiad’ – ‘The Olympics Under the Dictator’).

The following year, she curates the international exhibition foto ’37 held at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, becomes a member of the Bond van Kunstenaars ter Verdediging van de Kulturele Rechten (BKVK, Artists’ Association to Defend Cultural Rights), and starts a relationship with graphic designer Wim Brusse (1910—1978).

After the German invasion of the Netherlands and this institution of their Journalism Decree of May 1941, Eva can no longer publish under her own name because of her Jewish background, so contributes to periodicals under the name of Wim Brusse and makes portrait photographs for a living. She then goes underground to forge passports for the illegal group Persoons Bewijzen Centrale (PBC, Identification Centre).

These are experiences which contribute to her separation and eventual divorce from Fernhout (who had migrated to the USA) and a greater humanism in her neorealistic photography after the war. Mother of two children (Berthus, born 1945, and Iara, 1948), she has experienced the conflicting demands of motherhood and profession.

The feminist emphasis in her work of this period brings her inclusion in Edward Steichen‘s survey of European photography at MoMA, and his world-touring exhibition The Family of Man (1955) and in the 1970s, she is committed in the Dutch Marxist feminist movement Dolle Mina, participating, not only as a photographer but as an activist, in the street performances which mix humour and provocation in a festive atmosphere.

From experiences that she shared with her friends, with Charley Toorop, with companions and the wives of men around her: of risky contraception, illegal abortions, child care on top of a professional career and the double social standards weighted toward the advantage of men, Besnyö chooses to broadcast the actions of the group and to campaign, through her portraits of them, for women entering professions previously dominated by men.

To search for an aesthetic ‘style’ in Besnyö’s oeuvre, and amongst her 3,225 images held in the collection of the Maria Austria Instituut Amsterdam, is to overlook her subjectivism, a characteristic of feminist imagery which leads into the ‘multiplicity of styles’, or more properly an abandonment of patriarchal art history’s ‘march of styles’, by postmodernism, in which mere aesthetics are malleable, pressed into the service of an expression of women’s, and the human, experience.

In my early days, form was more important to me than a theme and it slowly reversed until the feminist movement. Suddenly, the theme had become more important than the form. Then the form got the upper hand. Form is essential to me. […] I hope I have now found the perfect balance between form and content.

Eva Besnyö, interviewed in 1991

4 thoughts on “December 12: Liberation”