January 14: Photography as resistance is the subject of this post.

January 14: Photography as resistance is the subject of this post.

Emmy Andriesse, born on this date in 1914, is best known for her photos of Amsterdam, the city in which she spent most of her tragically short 39 years, during the Dutch Hongerwinter famine of 1944-1945.

Other documentary photographers born this day are Randolph Bezzant Holmes (in 1888) and Giorgio Lotti (1937).

As a social documentary photographer Emmy Andriesse was a humanist. Nearly all of her wartime photographs are in effect street portraits. Her subjects usually face the lens and are aware of her presence as a photographer, and this interaction is a distinctive sign of her empathy.

Andriesse received training in photography as part the experimental design course taught by socialist graphic artist Paul Schuitema (1897–1973), and exponent of the ‘New Photography’ Gerrit Kiljan (1891–1968), at the Academy of Art in The Hague. With other students of Paul Schuitema, Andriesse lived in a communal home in Voorburg. From second year she was so passionate about photography that she became known as ‘Emma Leica’ though as she became more serious she switched to a Rolleiflex.

With the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War she joined the Aid to Spain Committee and through it, in 1936, the photographic and film department of the anti-fascist Union of Cultural Rights. Thus Andriesse came into contact with young, socially concerned reportage photographers such as Eva Besnyö (1910–2003), Cas Oorthuys (1908–1975) and Carel Blazer (1911–1980).

Mirelle Thijsen writes that before the war, photographers were permitted into their own division of Nederlandsche Vereniging voor Ambachtsen Nijverheidskunst (the Dutch Society for Craftsmanship and Applied Art, VANK founded in 1904) during its last years, from 1939 to the dissolution of the society in 1941. Those who joined were Carel Blazer, Emmy Andriesse, Eva Besnyö, Wim Brusse (1910–1978), Jan Kamman (1898–1983), Cas Oorthuys, Claar Pronk (1915–1996), and Lex Metz (1913–1986).

In 1937, she was young, independent and a professional embarking on a career in children’s portraiture to fashion, advertising and news photography in what was a prosperous country. Her first exhibited work was In Jordaan, a social documentary on the working class district of Amsterdam shot on 35mm (see above), shown at ‘Photo’ 37 ‘in the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam and was well received by critics.

In 1937, she was young, independent and a professional embarking on a career in children’s portraiture to fashion, advertising and news photography in what was a prosperous country. Her first exhibited work was In Jordaan, a social documentary on the working class district of Amsterdam shot on 35mm (see above), shown at ‘Photo’ 37 ‘in the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam and was well received by critics.

For naturalist and poet Rinke Tolman (1891-1983) she took photographs for his Zes maanden op speurtocht (‘Six months of searching’).

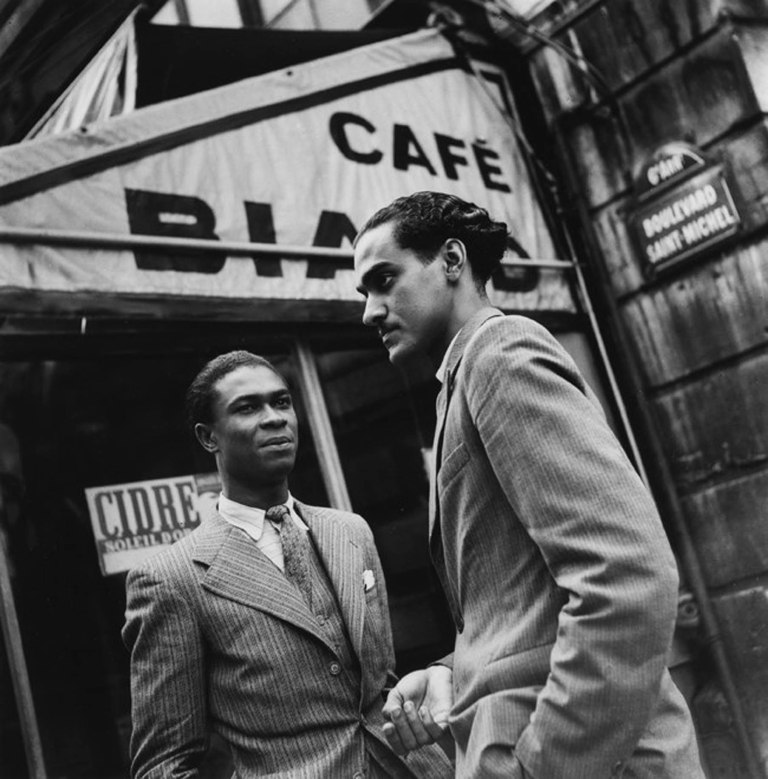

On assignment that year in Paris she photographed foreign students following the formal dictates of the ‘New Photography’ in which compositions are radically tilted, and angles of view are unconventional. Here she has moved to the medium format as her camera of choice, which she continues to use.

In 1941 she married fellow student Dick Elffers (1910–1990), a Protestant, who became an important graphic designer, but even so as a Dutch woman of Jewish heritage she found herself forbidden to work due to the German Berufsverbot (Professional Ban) directed at Jews, then had to wear the yellow star. In 1943 she was forced into hiding until 1944 when anthropologist Arie Froe (1907–1992) helped her to forge an authentic-looking identity card so that she could venture out to tae photographs once more.

Thus in 1944 she found herself amidst the events leading to the Second World War, which was to radically affect her country. She joined with Besnyö, Oorthuys, Blazer and others in De Ondergedoken Camera (The Underground Camera) whose aim was to document the war and the activities of German soldiers, and whose photographs helped to identify collaborators and war criminals after the war. Inevitably, her subject matter was human suffering.

I remember the story a Dutch friend, then a very successful engineer in Australia, told be about his experience, as a boy in the Netherlands during the famine, of helping to kill a horse for food, with a sledgehammer. The privations of course were much worse for the minorities, particularly the Jews, during the German occupation of Holland.

In 2008 the Dutch Jewish History Museum purchased photographs from the Special Collections Department of the Leiden University Library from which they mounted an exhibition of Andriesse’s images of the Hongerwinter.

Andriesse documented the pillaging and dilapidation of the Jewish districts after the deportations, people who like her were not allowed to get employment selling their possessions, and the starvation of the remaining people, concentrating her attention particularly on the children and elderly. Her unwavering camera belies the necessarily clandestine nature of her photography, though it is clear from the two photographs of the boy outside a grocery (above, and below) that she took her time when she could, and collaborated with her subjects in making her most poignant images.

To have photographed starving children must have been especially painful; sometime in 1945 her first son had drowned at the age of two.

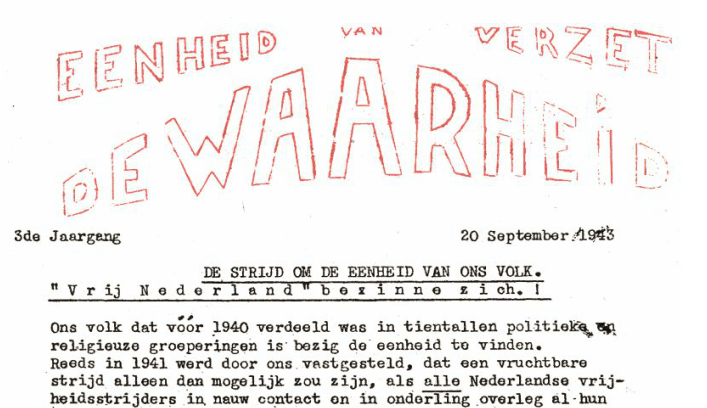

On the wall in the picture above of people warming themselves in the sun is painted grafitti ‘Leest De Waarheid’ (‘Read The Truth‘). This was the name of a mimeographed newspaper published in the Netherlands from 1943 by the Communist Party of the Netherlands (CPN) and distributed illegally, with at least 1,500 workers on the paper arrested and interned, and many paying with their lives (see research by Lydia E. Winkel). It fiercely fought anti-semitism.

The words have caught Andriesse’s eye and effectively serve to title her photograph. The aimlessly dawdling girl in the foreground sets a tone of melancholy while in the background a boy bends to get full advantage of the sunshine through his winter clothes and unwillingly idle men range themselves along the wall and catch up with news.

Also as part of the resistance, the newspaper De Vrije Katheder (The Free Lectern) distributed a pamphlet er moet veel strijd gestreden zijn (There Needs to Be Much Fight, 1945), an exceptional publication that made use photographs made by Andriesse, Oorthuys and Blazer amongst others.

Following the Liberation, on 1 September 1945, the Vereniging van Beoefenaars der Gebonden Kunsten (Association of Practitioners of Applied Arts, GKf ) was established and was an inspiration for a new generation of artists, promoting professionalism with a strong sense of solidarity due to the fact that many already knew each other before the war and that some shared a common history during the resistance. Among the first members of the photography division was Emmy Andriesse.

At the same time as documenting the celebration of the end of the war, she made poignant pictures of the plundered homes and desolate ruins in Amsterdam’s Jewish quarter.

In the postwar period she returned to fashion photography and magazine photography, and in 1946 she was the mother of a son again. However, determined and ambitious, she bucked convention and continued to work, leaving care of her child largely to friends and resigned herself to being a ‘Sunday Mother’.

Her major projects included a series of portraits of artists in their studios commissioned by the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam in 1948 – 1949, after which they commissioned another book on Van Gogh, which she was unable to complete before her death from cancer in 1953. It was published posthumously. She mentored Ed van der Elsken and wisely encouraged the young photographer to seek work in Paris.

An exhibition Photographie at the Stedelijk Museum in 1952 displayed works by the four protagonists of the post-war documentary humanism: Emmy Andriesse, Eva Besnyö, Carel Blazer and Cas Oorthuys and showed their applied work as well. It was a tribute to the GKf photographers and it drew the attention of overseas critics and international exhibitions of their work followed, including Edward Steichen‘s Post-War European Photography (1953) and The Family of Man (1955) which contributed to the group’s, and Emmy Andriesse’s international recognition, which, tragically, has come since her death.

Just as a reminder that resistance has not ceased, and cannot in our own era, Sayraphim Lothian, who was once my student, is issuing a book (currently for pre-order) Guerrilla Kindness and Other Acts of Creative Resistance (Booko gives a range of purchase options for Australian readers).

One thought on “January 14: Resistance”