Occasionally photographers, unknown to each other, will chance upon the same scene. It is instructive to consider such coincidences.

Occasionally photographers, unknown to each other, will chance upon the same scene. It is instructive to consider such coincidences.

Prompted by a newsletter from l’Oeil de la Photographie (well worth subscribing) I followed up their article on an exhibition that, Galerie Argentic, of 43 rue Daubenton, Paris has been working on for several years.

They have collected, especially for their exhibition Paris des Photographes (running tomorrow to March 7, 2020) fifty pieces representing Paris and its inhabitants from the XIXth century until today, including Martin Argyroglo, Eugène Atget, Edouard Baldus, Hippolyte Bayard, Marcel Bovis, Brassaï, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Claude Dityvon, Robert Doisneau, Jean-Claude Gautrand, Hubert Grooteclaes, Lucien Hervé, Izis, André Kertesz, William Klein, Gordon Parks, Janine Niepce, René-Jacques, Willy Ronis, Roger Schall, the Séeberger brothers, Yvette Troispoux, François Tuefferd, and Nicolas Yantchevsky. Most of it is a glorious trove of Humanist photography, some rarely seen.

Amongst the pictures was one, the subject of which struck me as familiar from a more famous image.

Gordon Parks, who in 1948 became the first black photojournalist to work for LIFE magazine was on staff until 1968, and a contributor until 1972, and during 1951-1953, completed two years in their Paris bureau.

He wandered into the Quartier Latin and down one of the oldest streets of the city, rue Mouffetard (left), a busy street market, and market street, and photographed it from beside the Gendarmerie looking north, across rue Ortolan. The Neolithic way which became a Roman road is named, it is said, from mouffette (skunk) for the odours of the once pristine stream the Bièvre which rises in the Verrières-le-Buisson, Île-de-France south east of Paris and ran under the south end of rue Bazeilles (formerly part of rue Mouffetard) and into Square Adanson (behind us in Parks’ photo) where a daguerreotype laboratory once added to the effluent coming from an area east along the river that was heavily industrialised with mills, tanneries, butcher shops and dye-makers built along its banks and all compounding the legendary smell.

Parks’ picture of the crowded street was made in bright sunshine.

It was perhaps on another excursion, in less crowded and much cooler conditions that, outside number 129, he encountered a man playing an accordion. We can make out in this sombre, low-key image a scarf-wrapped fruit seller at her barrow behind him and two children on the pavement.

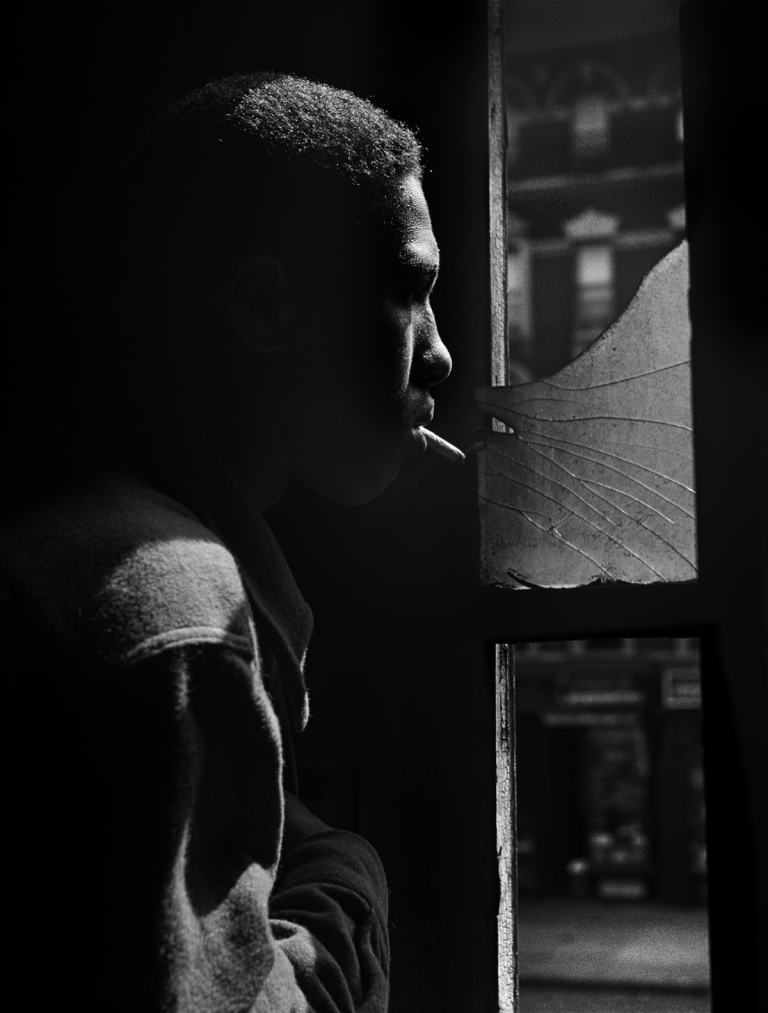

His camera, evidently a twin-lens reflex, is at the level of the man’s shoulder and perhaps Parks moved in so close because the man couldn’t see him; he is blind, as is indicated by the cane resting across the accordion case on which he sits, its white standing out as the brightest highlight in a scene which is top lit by the overcast light slipping into the narrow alley. Between his legs the accordionist clutches a small, open leather case to receive alms from the passers-by, and to prevent the theft of his money by those less charitable. Parks’ title for the image is simply Mendiant, Paris (‘Beggar, Paris’).

Moving out onto the street he shot another frame from the other side of the same subject, who, apart from playing his instrument, hasn’t budged. He seems still unaware of the photographer who captures the moment when a tiny, white-haired woman, rugged-up in a fur-collared coat and carrying a milk pail, pauses to toss a coin into his open case. Her hand is blurred, but we see plenty of detail; the chequered pattern of the lid and the stitching of its handle, the man’s old but brightly polished shoes with soles barely worn, his eroded and stained fingernails, the dirt on his baggy pants-cuffs, the chipped paint of the end of his otherwise very white cane, the encrusted texture of the pavement and the faux woodgrain of the wall behind him. One can read the brand, picked out in rhinestones, of the good quality but twenty-year-old accordion by French-Italian manufacturer Fratelli-Crosio.

Should we read Park’s photograph of a blind man as exploitative? He’d known poverty and hardship; and his biography is a classic story of rags-to-riches, thanks to a chance discovery of a discarded LIFE magazine prompting his pawn-shop purchase of a Voigtlander ‘Brilliant’ in 1942. It was the film-noir drama in the picture story “Harlem Gang Leader” that got him published in LIFE in Nov. 1, 1948 and shot him to fame.

He loved Paris and spent the two years there in the company of his family on a big salary and generous expense account, meeting the big names of Parisian culture, but the stories he was asked to do were fashion, or merely repeated cliché American perceptions of the French. He was itching to get back to his projects fuelled by his black consciousness.

The Causey family, after they appeared in his story on the 1955 bus boycott in Montgomery and racial tensions in Alabama, were chased out of their home as a consequence. They were not the only family for whom Parks got compensation to set them up again. We can conclude that his conscience over the blind man was clear.

It is Robert Doisneau’s picture of the same subject that I recognised in Parks’ photos, and it is a more famous image. Where Parks is interested in getting a good story, Doisneau likes to make a parable (in its non-religious sense of ‘discourse’ or ‘allegory’ from Latin parabola ‘comparison’), of love, lust, cheating, pride, death or folly, through often elaborate juxtaposition. In the case of a blind musician, his composition prompts us to meditate on unseeing and, being the moral of a photograph, it is one of his finest.

From his stance well out on the crowded street, Doisneau shows us the accordionist perhaps a year younger and in a balmier season for which he has dressed more lightly. The angle sets him on a stage of kerbstones and we, the audience of this dumbshow, are aware straight away that he is ignored—no charity here—unregistered by all but two people; artist who draws him discreetly, in steadfast concentration, from behind; and the unseen photographer.

His eyes are black pools in a stark skull, and directly above, the ‘No Entry’ sign weighs in on his sightlessness which cannot register the shaft of emerging sunlight light that falls towards, but does not reach, him. Doisneau thrusts the face of the woman beside him hard against the edge of the frame, and people behind him jostle against each other, staring at…something unseen.

Only an Atget photograph from fifty years before can satisfy our curiosity about what that something might be…

The blind man’s corner is at left, and we see it from the even narrower rue Daubenton (where, in another coincidence Galerie Argentic, at 43, in which you can see Parks’ picture, happens to be located). In the lane, on narrow tables and shelves on the wall is a fish stall with morues, lottes, maquereau, sole, merlans, l’aiglefins and raies stacked upon them, while wrapping paper flutters on a hook. The boulangerie behind the musician in Atget’s time sold fire-wood and coal. As usual, Atget manages that even in the popular market, no-one is seen.

Now, in this Google Streetview there is nary a clue of our tableau to be seen but the kerbstones and cobbles. The panelling and awnings have been torn from the corner, the crowds are dispersed at this early hour, and scattered individuals—tourists—are more occupied with their phones than with shopping.

The music is gone.

Stagnation is everywhere James…

LikeLike