Does a photograph sleep? Does it wake us?

Does a photograph sleep? Does it wake us?

Having a bit of time to spend in Albury, I dropped into the Murray Art Museum Albury (MAMA) and there encountered an exhibition that, while it contained no photographs, still provoked ideas about my favourite medium. Titled Zzzzz: Sleep, Somnambulism, Madness it continues until Sunday 18 August and was curated by Gertrude Contemporary gallery artistic director, Mark Feary, as part of the Melbourne International Festival where the show originally appeared last year, and rearranged for MAMA with their assistance.

Significant to my photographic take on this exhibition, Feary has worked in curatorial and programming roles at Australian Centre for Photography, Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography and the Centre for Contemporary Photography, Melbourne, among other appointments.

The sleeping figure has been a favoured subject in Western art, especially since a sleeping model presents a static pose that makes sustained drawing or painting easier, and accommodated the extended exposure times of early photography too; most famously in Hippolyte Bayard’s despondent Self Portrait as a Drowned Man of 1840. There are some sleepers here, but also dreamers, insomniacs and the psychotic.

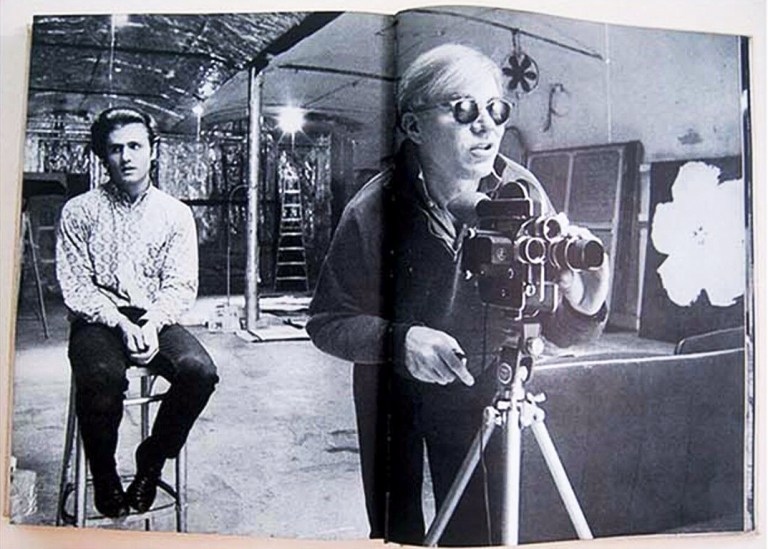

Almost predictable, but gratifying, is the inclusion in the show of one of twentieth-century art’s most-noted slumberers, John Giorno, in Andy Warhol‘s Sleep (1963). In an action repeated with still cameras before and since, Warhol trained his 16mm Bolex movie camera on the supine figure of his lover. Being awake while your companion is asleep suspends the activity of the relationship; while you are physically with them, they are absent in unconsciousness, and you are actually alone, but with time to indulge an examination of their physical appearance, attracted or repulsed, depending on the stage at which the relationship stands.

Due to the limited 30-minute magazine capacity of the Bolex, Sleep is not in fact a single 8-hour continuous take, but a montage of several made over a series of nights that add up to 5 hours, 21 minutes. The fact that the subject is barely moving makes this ‘anti-movie’ equivalent to the process Warhol might have undertaken with a still camera. However, the viewer must either persist and wait for the scene changes, or return every half an hour over the day in order to catch them.

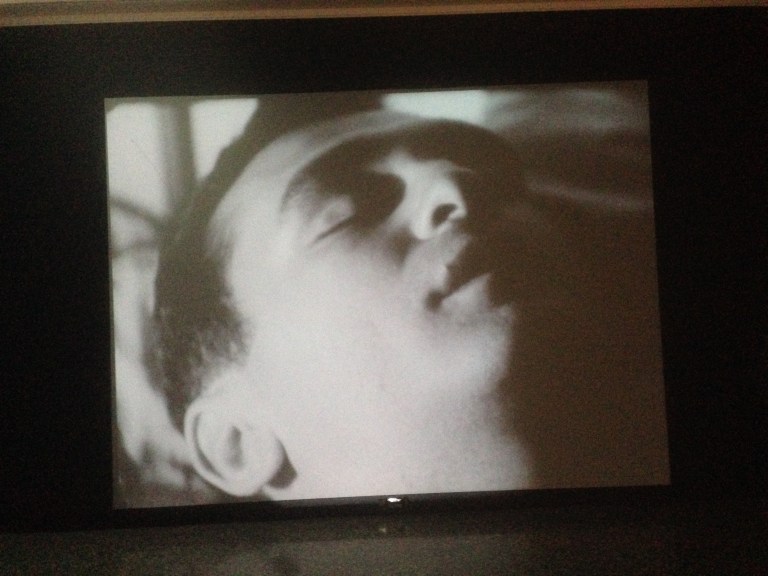

The satisfaction is in watching Andy’s camera being aroused by what it sees as it lingers on one nipple rising and falling with the subject’s breathing, before pale buttocks that fill the frame are exchanged for a chiseled profile and then even a view from above the forehead and along the inverted, and so strikingly phallic, nose of the dormant lover. Do we imagine we see ‘Rapid-Eye-Movement’ or are they the spasms of a lid deliberately held shut? It’s hard to be certain from the grey video copy of the grainy original film; is he really asleep or actually complicit in this self-conscious Pop Art hype? Will he change position? How long must I watch? Is anyone watching me, standing motionless, as I watch? The series of relentlessly long, 30 minute scenes allow the viewer’s mind to wander and provoke such random thoughts.

That’s the difference in watching these barely moving scenes compared to contemplating even the most moving of stills; you endure with a Sisyphean patience before it dawns that you would not do this with a photograph except when it is in the developer tray. We don’t watch photographs, we look at them, but this is an exercise in watching someone else, through their camera, looking.

Nearby is Sleep Symphony in which clinical observation replaces eroticised ogling, though it is in part inspired by, or at least nods to Warhol’s Sleep in being a 45-minute real-time recording of sleeping figures, made possible with digital video technologies unavailable to the 1960s Pop artist.

Murray-Leslie and Melissa Logan of the international collaborative group Chicks on Speed (who don’t play guitars) undertook a residency at SymbioticA, in the Sleep Department of the University of Western Australia. They collaborated with Shannon Williamson, a fellow artist-in-residence with previous experience in the laboratory and who was undertaking her own ongoing sleep study. They discussed the different cycles of sleep, and the values, parameters and types of data they could collect from the sleep studies.

Murray-Leslie and Melissa Logan slept in the laboratory in costume thus “performing” in the sleep department while asleep. Meanwhile Shannon Williamson collected the data which was then synthesised into sound and visual effect algorithms. Murray -Leslie explains that in the gallery;

“people could come and watch us asleep and the music and visual art we were making whilst asleep…creating the Sleep Symphony”

Opposite, across the darkened gallery and high on the wall is a clock. All ordinary working clocks to the casual glance seem as static as one in a photograph; they display a time which may, or may not, synchronise with the clock in your head—then they’ll show another time as you look back.

They are ‘clockwork’, not metaphysical nor human, and the time clocks measure is contingent. It seems to stretch or contract depending on where you find them; at work, or at the station; and depending on your mental state, whether expectant, impatient, bored, frantic or late. Any photographer of the old school is familiar with the face of their GraLab timer glowing greenly in the dark, prompting as sheets of film are marshalled in procession through baths of chemistry before they reveal what was made latent in that fraction of a second of their exposure.

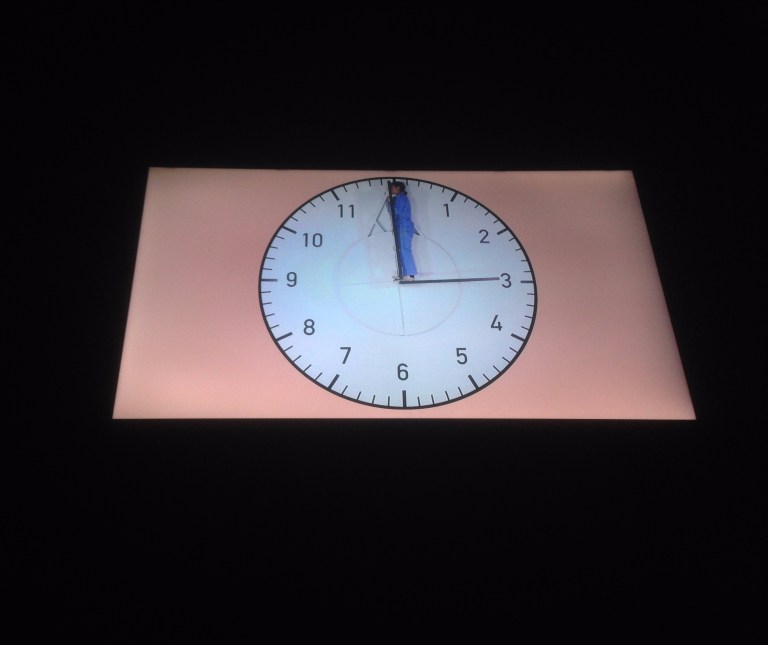

By joining her human body to machine time, and by deliberately depriving herself of sleep, Kate Mitchell (*1982) sets herself a formidable task of endurance on the hands of Tyrant Time, clinging to them as they creep through 24 interminable hours.

“I physically have to go through the situation of ‘What does it feel like to be in that situation?’ Over time those things are revealed, so at 3am I’m hysterical and crying – I’m beside myself with this idiotic thing that I’ve put myself into. And then the next hour is the most serene experience.”

The video projection overlooks the rest of the exhibition and is mounted just beside the entrance so that it is not seen immediately, of mistaken at a glance for just another wall clock, and given its slow pace, it lends itself to being represented as a series of stills, but even more than the Warhol, it rewards a long engagement.

Unlike Harold Lloyd‘s, Mitchell’s situation is too monotonous a performance to be played for laughs, and is more akin to that of the desperate underworld workers of Fritz Lang’s 1927 Metropolis. The hour hand is a grim steel bar, while the minute hand is a ladder on which Mitchell perches, reclines or hangs, sometimes precariously, and it is a spartan support rarely comfortably enough to allow a few minutes rest before it once again turns to a position where clinging to it requires agile effort. As the title implies, she is not just on time but In Time.

A separate booth shows a work by Barbora Kleinhamplová (1984) Sleepers’ Manifesto which is presented in two forms; a video projection and video of a three-act play with six actors that can be viewed separately in the gallery foyer.

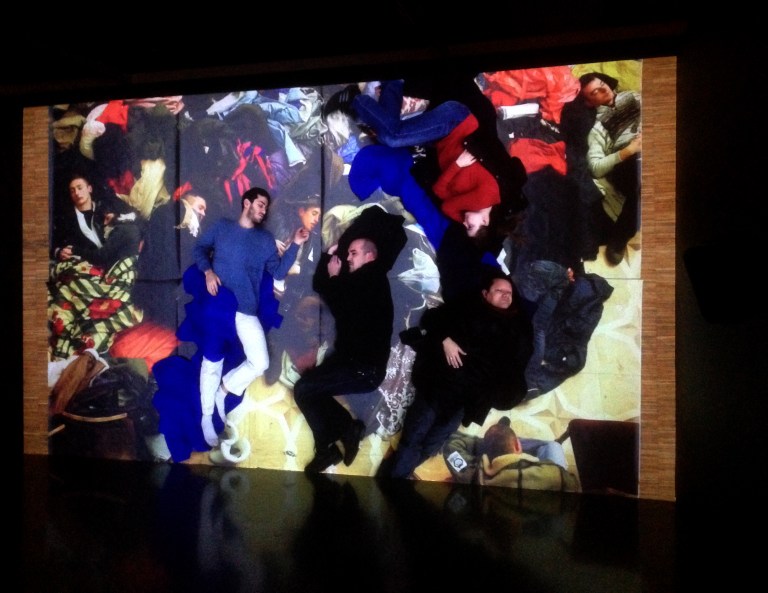

The work is controversial in that it commandeers a press photograph by fellow Czech Filip Singer (*1980) who is not credited on the wall notice, and who could be said to be the ‘sleeping’ collaborator, along with theoretician Tereza Stejskalová who assisted in the production of the companion works shown at MAMA.

Singer’s photojournalistic image, an elevated view of Euromaidan protesters sleeping on the floor of the Kiev hall, has been reproduced life-size as a multi-sheet patchwork that fills the screen. Uncannily, Singer’s photograph speaks; each of four actors lying on the mural-scale print rouses in turn to recite their monologue, not haranguing, but in a drowsy, hypnotic voice quite at odds with the urgency of their words. They protest against the erosion by late-capitalist economic pressures on our sleep that steal free time and demand unrelenting engagement and presence. The spoken manifesto insists that sleeping be valued more than such enforced wakefulness, and not be despised as a suspicious, subversive act:

“Sleep has been stolen from us;” “We are forced into ‘Sleep mode’ in which machines exist—neither turned on nor off;” “Sleep has become a type of revolt;” “We are alone in sleep although we share this state with everyone;” “The duty of society is not to keep us awake, but to protect our sleeping bodies;” “Give us back our sleep.”

Their speech is didactically illustrated, as in a Powerpoint show, with further superimposed images, gleaned from the internet, of workers sleeping in makeshift beds, hidden or stealing slumber at their workstations in factories, offices and building sites. The sleeping students seen beneath and around the actors meanwhile, have just (in the December prior to the creation of this artwork) occupied the Kiev Town Hall in protest over the crisis in Ukraine politics that later led to escalating hostility from Putin’s Russia; military intervention and annexation of Crimea and the beginning of war in Donbass.

Is it legitimate to employ Filip Singer’s photograph so soon after it was news, and those of other, anonymous photographers, in this manner, and for different political purpose? That sleep, or the lack of it, is a major political, societal and health issue there is no doubt, and it increasing affects people across the globe as the poorly regulated gig economy is imposed, especially on the disadvantaged and younger demographics. For Kleinhamplová, recruiting an image from the Euromaidan protests, serves her artistic investigation of a more urgent, broader struggle between contemporary political and economic institutions and the various publics they are meant to serve.

Sleepers’ Manifesto, first shown at New Museum, New York in 2014, subsequently has been much examined and debated as ‘agitprop’. It was also included soon after its production in October 2014 in an exhibition that was held at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna amongst the discussions, workshops and a joint publication of students from the Academy of Fine Arts Prague, the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna and the Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design in Prague, around Mario Perniola‘s book Art and Its Shadow. Sleepers’ Manifesto continues to attract attention and was featured during March this year in Eyelids Mirrored Within at Tenderpixel, London, amongst recent works by Czech and Hungarian artists for whom dreams represent resistance and freedom.

Kleinhamplová is the founder (together with artist Eva Koťátková) of the Institute of Anxiety and her collaborations encompass different disciplines and professions using group interactions of actors and non-actors to examine and test what constitutes a functioning society, and what is the role of an individual is within its systems; thinking that has resulted in her 2014 book Kdo je to umělec? (‘Who is an artist?’) co-authored with Tereza Stejskalová (published in Prague by Akademie výtvarných umění).

There is much depth amongst this selection of works, and the others selected by Gertrude Contemporary’s Mark Feary with MAMA, some dreamy, some fearsome, and together they provoke new thoughts about the dormant state and the apparently static image.

2 thoughts on “July 9: Sleepy?”