September 23: The category ‘classic photo’ is a popular, recurrent hashtag in social media. It refers more specifically to images of France from the period 1930-1960.

September 23: The category ‘classic photo’ is a popular, recurrent hashtag in social media. It refers more specifically to images of France from the period 1930-1960.

These pictures evoke un je-ne-sais-quoi, a longing and a romance. They appeal to current generations as much as to any who remember, or yearn for a visit to that country. The term ‘classic’ represents notions of a ‘past perfect’ to us now as much as did the classical world itself in the 18th and 19th century, inspiring the Grand Tour and much early photography.

The spirit of these images is not coincidental nor unintended, nor is it to be mistaken for a factual representation of France. In them we can distinguish the subjective nature of ‘documentary’ photographs, a narrative realism rather than direct transcription, but one that retains a reportorial intention.

The photographers who produced these pictures were doing it commercially. Few would have regarded their work as ‘artistic’ but rather as documentary, or editorial. Their pictures sold to the picture press, the illustrated magazines that thrived during this period in France, pioneered by L’Illustration (1843–1944, 1945–1957) the first French newspaper to print a photograph (1891) and the first colour photograph (1907), and others including Documents, a Surrealist art magazine (1929–30) edited by Georges Bataille, the popular Vu (1928–1940), Le Monde illustré (which published photographs after 1914 until closing in 1940). More appeared post-war, including Le Monde illustré (which resumed publishing until 1956), Réalités (1946-1978), Paris Match (founded 1949) which had a circulation of 1,800,000 copies in 1958, overlapping with the uptake of television in France from the late 1950s which as in most countries, superseded the picture magazine.

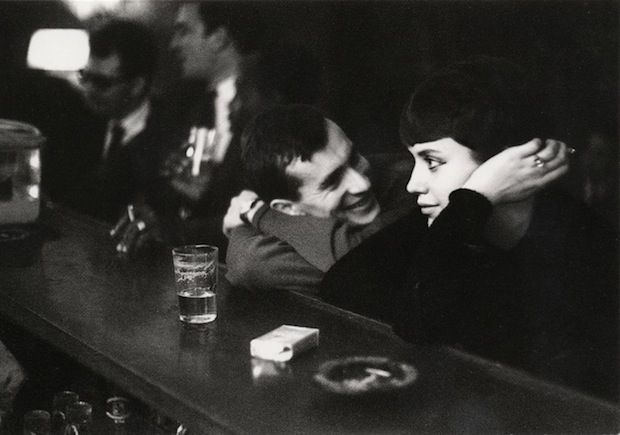

These photojournalists found a ready market internationally in magazines such as Life and Picture Post which, for example, published in its entirety Doiseau’s series (commissioned in 1948 by Life) Le regard oblique revealing Parisians’ reactions to a slightly risqué painting of a cheeky nude as they were photographed from inside the window of the Romi Art Gallery, while Life‘s issue of 12 June 1950, devoted pages to his imagery of kissing French couples.

The imagery they produced has been labelled ‘humanist photography’ about which you may read more in this Wikipedia entry that I wrote in February 2016. In brief, this was a photographic paradigm that can be seen developing in French photography before WW2, with Kertesz and Brassaï, and which resolves into a national self-image after liberation. As Willy Ronis, one of its best known practitioners beside Doisneau, Izis and Cartier-Bresson, recalls:

This atmosphere of what I would call feeling, which is strongly imprinted in my photographic choices of the time, it was not simply due to my character and my sensitivity, it was equally present in the ambience of the moment, since we had rediscovered liberty, and we felt very united. There was no longer the fear that existed during the Occupation, of not knowing what your neighbour was thinking, for sometimes it was dangerous to speak to your neighbour, because every so often there were denunciations…and then all of a sudden [after the Liberation] there was a free press, the occupation force were gone. It was over and we were all together again. […]. That changed everything.

The structure of French society, depleted by 1,450,000 at the end of the war, was not only rebuilding, but changing, bringing new respect for the worker, la classe ouvrière who had formed the backbone of the Resistance.

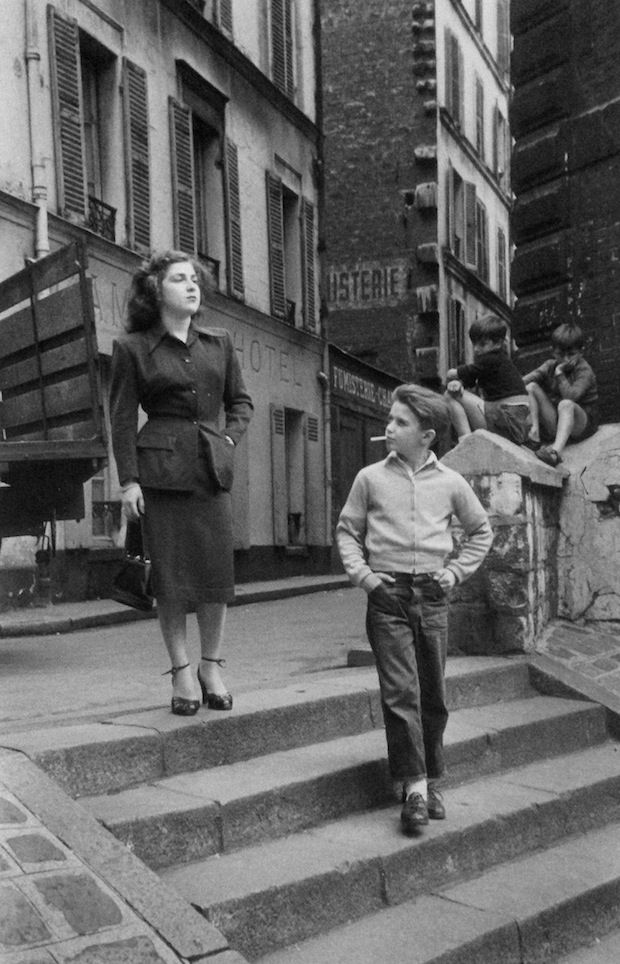

Though life was hard and housing difficult to find, with Paris being flooded by a rural exodus and by postwar refugees, the new sense of optimism and solidarity amongst a classe populaire (the ‘little man’) was promoted by the predominantly leftist, often communist, humanist photographers as an agreeably and distinctively French demographic.

- Paul Almasy (c.1945-50) Poultry Farm in rural France.

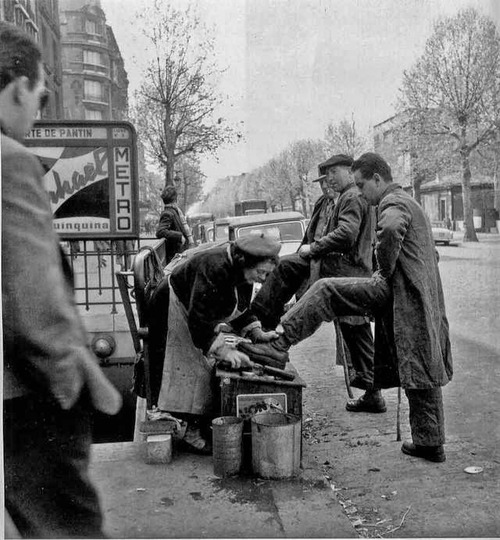

They are the definitive street photographers. It was on the street, in the bistrot and bars, fairs and markets of Paris, amongst its distinctive settings and landmarks, and in the rundown banlieues and makeshift bidonvilles, that they found their favourite human subjects; workers, families, lovers and children, and the homeless clochards, enacting what the writer Pierre Mac Orlan (1882-1970) called the fantastique social de la rue, the everyday theatre of the street.

Paul Almasy (*1906) who died this on this date in 2003 subscribed to the paradigm of the humanist photograph and applied its principles and approaches, its ‘style’, not only in France, but to his own native country Hungary and he continued to embrace it in images he made around the world in work he did for the United Nations.

He settled in France in 1938, two years after fellow countryman André Kertesz had left for the USA, and from there travelled the world, always with the City of Light as his home base.

His extensive oeuvre includes humorous images, like the one above, which are reminiscent of Henri Cartier-Bresson’s wry observations or Robert Doisneau’s often contrived or restaged situations. Here it has been a matter of anticipation as the bill poster reaches his paste-brush into the corner and thus appears to imitate the graceful leap of the showgirl skater.

Employing the billboard as a foil to, or a commentary on, the activity on the street appears as early as 1932 in Cartier-Bresson’s famous Derrière la gare Saint-Lazare and shortly after, in André Kertesz’s 1934 more formalist setting of figures against a wall of Dubonnet posters.

Born and growing up in Budapest, Almasy received a degree in political science in Germany and Austria between 1924 and 1928 in preparation for a diplomatic career but was attracted to journalism, accepting a first mission as correspondent in 1925 in Morocco during the revolt of Abd el-Crimea insurgents. He was reporter in Rome from 1929 to 1931 for the German press agency Wehr.

After first using the camera in 1935 he was impressed with its power to illustrate his articles. In 1935, in order to illustrate his articles, he produced the first photographs as part of a South American campaign. In the following years, Almásy crossed the Sahara in 1936 for the Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung by car, and to the end of the 1930s continued traveling around Africa, wielding his Leica and Rollei, to Morocco, Niger, Benin, Togo, South Africa, Djibouti, Zanzibar, Réunion, Madagascar, the Ivory Coast, Mozambique, Namibia and the Belgian Congo.

It was only after more travel in Latin America that he settled definitively in France in 1938. Other humanist street photographers of Paris supplemented their income with work in other types of photography such as portraiture, fashion and industrial photography, but Almasy’s efforts were a part of his established career as a journalist, and seasoned photojournalist, and supported by his knowledge of politics and current affairs.

Hired by the Swiss publisher Ringler & Cie he wrote and took pictures for them 1940–3 from France, Belgium and the Netherlands. After the war, though the numbers of his pictures of Paris increase, he also traveled widely elsewhere, including to Indochina in 1950 where the French were fighting the Viet Minh until 1954.

From 1952, Almásy worked on behalf of UN institutions like UNICEF, WHO and UNESCO, for which he traveled as an accredited employee. In 1957 Almasy returned to Africa, this time visiting Zaire, Mozambique and Zanzibar. There he photographed the Bayaka (pygmy) peoples, camping in his car in order to be close to them and to witness their nocturnal lives.

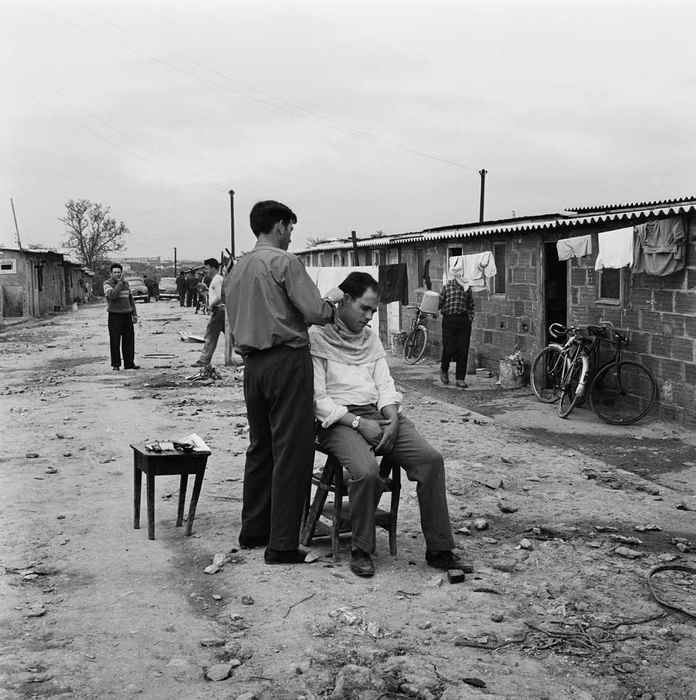

Clearly his background ensured that he was alert in Paris to signs of political activity in the street and to the social changes around him, especially in the effect of migrant workers during this time of frenetic rebuilding, in his visits to depressed banlieues and bidonvilles.

While he also circulated in high society Almasy continued to relate to the classe populaire of any country “people like you and me,” but also, but also of all classes, ethnic and socially marginal groups, people from upper and lower classes. He became known to, among others, Otto von Habsburg and Baron Rothschild, and interviewed, photographed and reported on such important figures of the time as Begin, Khrushchev, Eisenhower, Charles de Gaulle, Mussolini, Pandit Nehru and the Shah of Persia, Rezah Pahlevi.

Almásy portraits of creative arts personalities, such as Alberto Giacometti, André Breton, Colette, Jean Cocteau, Jacques Prévert, Man Ray, Romy Schneider, Alain Delon and Yves Saint Laurent are notable.

From 1972–1989 Alamsy held professorships in journalism in Paris at the Sorbonne and at the Centre de perfectionnement aux affaires de Paris. Nevertheless, his summation of his capabilities as a photographer is modest;

It was always coincidence that decided everything, I never searched – my camera was the viewfinder, I was just the finder.

You’ve not heard of Paul Almasy before? Little wonder. It has proven difficult to obtain examples of his archive for this article. 120,000 negatives are in the hands of AKG and cataloguing of them has yet to be completed. In 1995, Paul Almásy sold his colour photographs to Corbis. What has been published in the last few years shows, however, that much work by a great photographer is lost to us.

What is the appeal of humanist photography? Is it that in this era of ‘false news’ that we value its optimistic perspective, its concentration on a simpler everyday, its remembrance of le temps perdu, its large families and honest workers? Is it the wry but respectful humour set against recognisable urban landmarks?

Does just being in monochrome make them ‘classic’? Clearly not, because immediately following, in the 1960s, came more cynical, more aggressive photographers of American and Japanese, rather than European, subjects for which their use of contrasty black and white transmits a contrary and caustic tone; brash iconoclasts like Diane Arbus, Robert Frank and William Klein; or those with a more oblique, perplexing take on the street photograph, like Lee Friedlander and Gary Winogrand.

Given those developments, and the conditions of our information-hungry, pessimistic, divided and distrustful society is it possible to ever retrieve genuine humanism in photography?

That it so invokes our nostalgia answers that question; non!

2 thoughts on “September 23: Nostalgie”