March 27: It is the amateur’s mistake to think one must journey to the photographic subject. It is in front of you already.

March 27: It is the amateur’s mistake to think one must journey to the photographic subject. It is in front of you already.

Schweizer Kameramuseum, Le Musée suisse de l’appareil photographique, Grande Place 99, 1800 Vevey, Switzerland presents Me: Here Now, by Corinne Vionnet, or should one say the exhibition is a collaboration between Vionnet and several thousand others? Those thousands have traveled far to make the pictures, while the artist herself has produced the exhibited work from internet downloads.

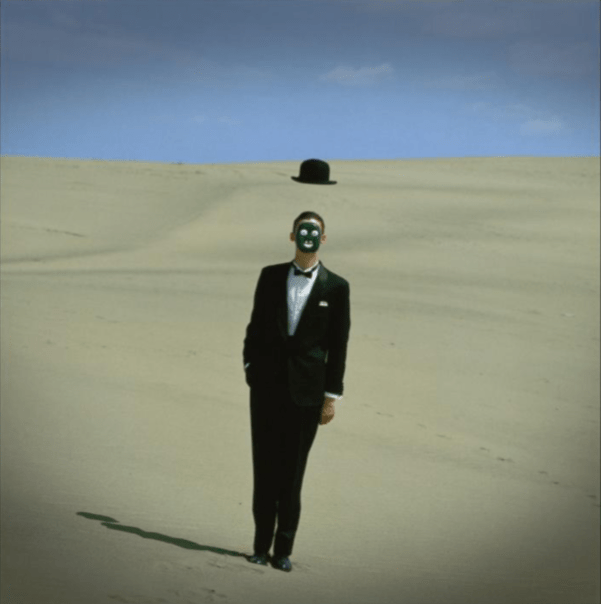

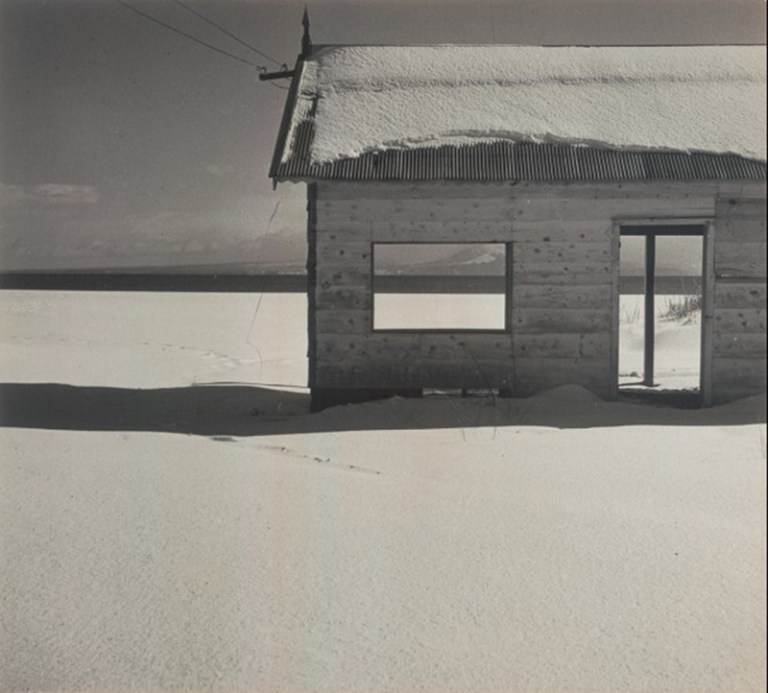

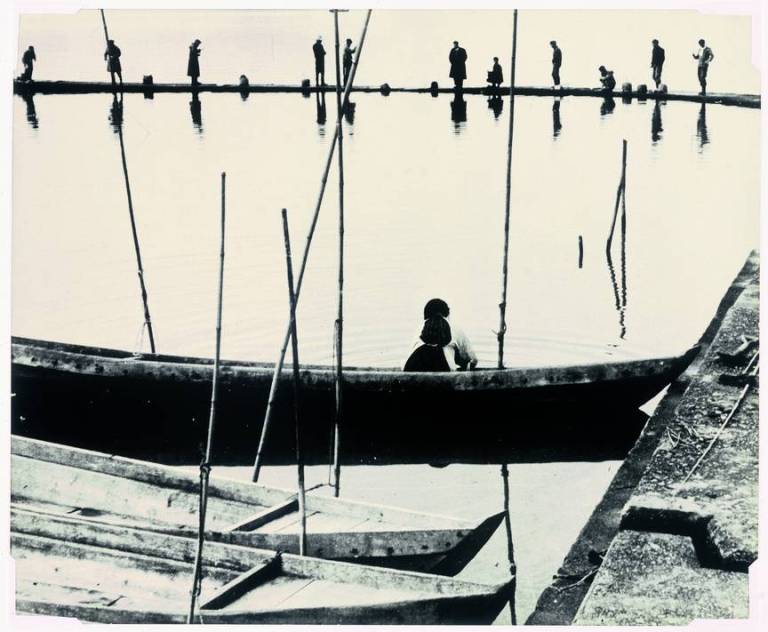

Shoji Ueda was born on this date in 1913 in Sakai (now Sakaiminato) in Japan, from which place he never strayed far. His photography was done largely amongst the dunes outside his door, or indoors.

Vionnet deals with that phenomenon of the tourist snapshot of the famous monument. To photograph, say, the Parthenon or the Eiffel Tower is just what one does after having journeyed to see it, and so it has been since the advent of photography.

For this exhibition, she produces photographs, video captures, of the tourists immortalising their memories of Sacré-Coeur.

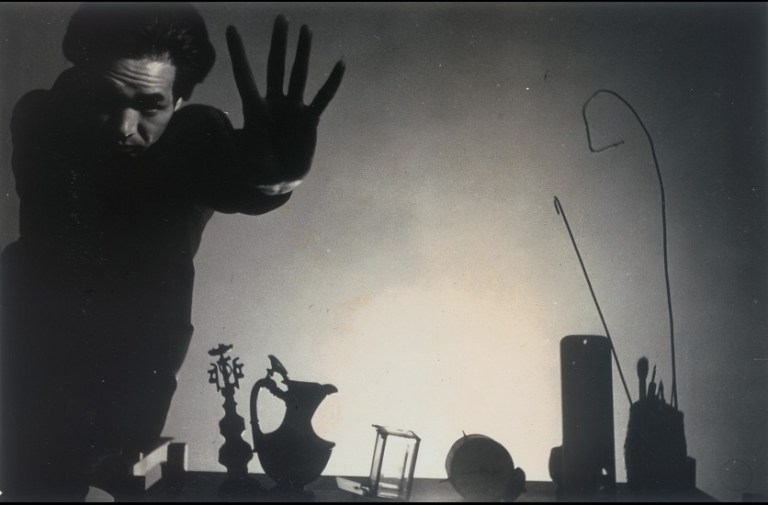

Each of them is producing, and often sharing in the same moment via social media, a view identical with every other, though unique for the individual. They are rendered anonymous; each just one in thousands thronging the site in Montmartre every day, their face concealed behind their mobile phone or camera and any identifying detail further obscured in a haze of pixellation in Vionnet’s blown-up grabs from the monochrome video on a screen which shimmers with magenta and cyan artefacts and aberrations. Each becomes a cyclops, a collective of one-eyed witnesses, whose monocular devices will flatten, miniaturise and simplify the scene in front of them, so that they can carry it away as an icon, and broadcast it as a consumer acquisition.

Before this, those who could afford such an extravagance as travel, especially to undertake the Grand Tour, would make a drawing or watercolour. His failure to use one device made to assist in producing such drawings, the camera lucida, was the prompt that Henry Fox Talbot (1800–1877) needed for his invention of photography, and the other inventor of photography Jacques Mandé Daguerre (1787–1851), had prior experience in producing dioramas that were a virtual reality version of travel, for those who could not afford the real thing.

It is rather odd that so many people are traveling in order to take almost exactly the same picture of the same thing and especially so when they and everyone else knows exactly what it looks like. Vionnet multiplies this conundrum. She has piled hundreds of these impression, gleaned from Instagram and other social media, upon one another, to make a kind of meta-postcard.

These views of the monument might considered the converse of the ‘selfie’ and nowadays they are usually combined; the Colusseum appears with the tourist photographers face looming in front of it, thanks to that ludicrous device, the selfie-stick, a kind of Wand of Onanism on which perches the phone to broadcast to the world, Veni, vidi; “I was here, I saw it;” “See me seeing myself see it, see me;” “In exchange for that airline ticket, this is what I got.”

Shoji Ueda’s pictures on the other hand, mostly consist of nothing, just sand. Here, in one photograph, is his oldest son holding what looks like a snapshot of his wife, but which turns out to be actually his wife, Norie Shiraishi, far away on the dunes, enclosed inside a little frame that the youth holds up—a fact we can confirm only because we can see her legs extend below the frame, so convincing is the illusion.

When I was young, I used to tell myself I should go to the dunes when at a loss for a theme. The vast dunes that lay before me like the body of a naked woman presented a world of typical simplification of sand, air and water.

He personifies the dunes as a woman, but not just any woman, but as his wife; she who supported him in his photographic endeavours. When, having lost his beloved wife in 1983, Ueda’s second son Mitsuru, an artistic director in an advertising firm suggested he accept a commission for a catalogue for fashion brand Takeo Kikuchi, he returned to the the dunes.

He then began undertaking numerous fashion shoots, most notably for BRUTUS magazine’s fashion pages (1985) as well as advertising shots for agnès b and Kindware (1986, 1989 respectively), compiled later into the series Mode in the Dunes. It gave Ueda a focus in his grieving and revived his creative drive.

- Shoji Ueda (1983/2011) from Sand dune mode, 2011 colourised digital print, 24.5 x 24.1 cm from 1983 negative.

His is the same trick as is used by further thousands of tourists, the more ‘creative’ ones, who when they encounter the Pisa Cathedral tower, ask their travel partner to kneel on the grass, between them and the monument, and to hold up their arms so that they appear to be bravely preventing its collapse, or to be deliberately pushing it over.

Its all done through through that fatal ‘flaw’ of the camera, its flattening effect, that makes telephone poles grow out of people’s heads; its two dimensional translation of three-dimensional reality, dictated by its monocular vision, assisted by the effect of depth of field that equally focuses things distant and close.

Equally flattening is the effect of Vionnet’s superimpositions, despite that they are a conglomeration of multiple views, all slightly different and some radically so, because in layering them she has aligned the main outline of the monument itself, so that surrounding it the anomalies of the variation in the legion of viewpoints are obliterated, mingled in a foam or mist of repetition.

One might expect a kind of Cubist rendition of the subject since it is seen from multiple viewpoints at once, but that is only apparent in Vionnet’s montage of snapshots of the simple form of the Kaaba (ٱلْـكَـعْـبَـة), “The Cube” in the Hejazi city of Mecca (above), that such a sensation is apparent, in a kind of rotation, like the Ṭawāf (طَـوَاف) made seven times around the Kaaba in a counter-clockwise direction that is completed every year by nearly two million devout Muslims from all over the world during their Haj pilgrimage. Because the Kaaba in its plaza is surrounded by arches, the views from extreme and even opposite angles merge more homogeneously to set in motion a giddying rotational perspective, the viewer being swept up in the circumambulation.

Repetition is a theme too in Ueda’s imagery; his most famous, and quite early image made at the beginning of WW2 in the dunes being a frieze in which four girls appear, evenly spaced and posed to present a wordless narrative. Architect Shin Takamatsu (*1948) in building in 1995 the Shoji Ueda Museum of Photography in Tottori, in memory of Ueda, drew inspiration from the figures in Four Girls and transposed them into the four exhibition spaces of the building that protrude above the horizon of the roofline (see above), one split with a slit window to represent the sitting girl.

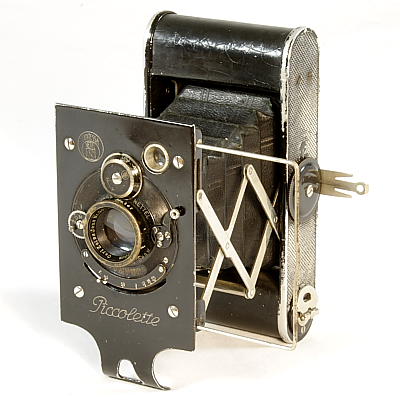

Ueda discovered photography in 1923, at age 10, when his neighbor, a young man, showed him how he printed photographs in his living room converted into a dark room by covering a light with a red cloth. Ueda was enchanted by seeing an image materialise on a blank sheet of paper.

However it was not until 1929 that his father Tsunejuro Ueda relented on his ambition to have his only son take over his business making Geta (Japanese sandals), accepted the boy’s love of the medium, and bought him a decent camera.

After graduating in 1931 from High School, Ueda joined Yonago Shayukai (Yonago Photography Circle), and was inspired by a special issue of The Studio magazine o that year featuring ‘Modern Photography’; European avant-garde photography was a strong stimulus, but something that he did not slavishly follow.

His picture A Boy on the Beach won him his first award, Camera magazine’s monthly prize for December. In 1932 his training in photography began in the photo studio of Mimatsu Department Store in Hibiya, Tokyo and he then enrolled at the Oriental School of Photography for three months.

On return to Tottori, his education had equipped him to open his own photo studio. In August, a landscape won him a commendation from Nihon Koga Kyokai (the Japan Photographic Society) and he joined the association, and locally set up a local photographers circle, the Nihonkai Club (Japan Sea Club), in his home town of Tottori and began a campaign of entering monthly contests of photographic magazines such as Asahi Camera and Photographic Salon.

WW2 took its toll on the civilian population and for Ueda there was no exception; called up for military service at the Hikari Navy Yard in Yamaguchi Prefecture, he was immediately sent back to his hometown due to his poor health due to malnutrition.

After the end of the war in the summer, Ueda was inspired to return to photography after seeing an article in the Osaka Asahi Shimbun announcing a public contest for acceptance into the Asahi Shashin Tenrankai (Asahi Photograph Exhibition).

He joined Ginryusha, a photographers group, together with Yoichi Midorikawa in 1947 and in 1949, with Ken Domon and Midorikawa, he participated in a competitive photo session at Tottori Sand Dunes for an editorial project conceived by Kineo Kuwabara , then the editor in chief of Camera, which he published in the September issue of the magazine, following it up with Ueda’s photo series, My Family, in its October issue.

He joined Ginryusha, a photographers group, together with Yoichi Midorikawa in 1947 and in 1949, with Ken Domon and Midorikawa, he participated in a competitive photo session at Tottori Sand Dunes for an editorial project conceived by Kineo Kuwabara , then the editor in chief of Camera, which he published in the September issue of the magazine, following it up with Ueda’s photo series, My Family, in its October issue.

In 1954, Shoji Ueda won the Nika Prize, in 1958, his works were selected by Edward Steichen for an exhibition at MoMA. These were recognitions that Ueda had entered the mainstream.

Many label his work as surreal, but he preferred the term ‘surreal-like’, emphasising that it was iconoclastic or deliberately provocative in the Japanese context.

His characteristic use, as props, of hats and umbrellas would seem to invoke René Magritte (1898–1967) who had started painting scenes with figures wearing bowler hats between 1926 and 1930, though he did not paint another until 1938, the year after Ueda’s image.

There is no doubt that the photographer was inspired by the Belgian surrealist and by Yves Tanguy, whose unearthly plains harbour unfamiliar objects in a moonlike light. Ueda’s studio shot pays homage to Tanguy, but also recreates the experience of the dunes.

This is my studio. You can not find a more perfect background, the horizon stretches to infinity. The dune is an almost natural photographic landscape. It is nature but reduced to a single background.

His last series, Illusion (1987 – 1992), produced when he was in his seventies, differs considerably from his signature style, being in colour, and returns to his studio experiments of the 1950s, and as he did there, he recreates within four walls, using double exposure that imports into the studio that numinous background,

Though he did journey to Europe in order to supervise the hanging of an exhibition in 1970, he did not travel, and the unique individuality of his imagery despite his working only locally, is a reminder that good photography is measured by originality, rather than by kilometres.

4 thoughts on “March 27: Pilgrimage”