April 23: In face of the increasing overlap of video and still image, the contemporary photographer might constructively question the conventions of their medium.

April 23: In face of the increasing overlap of video and still image, the contemporary photographer might constructively question the conventions of their medium.

Camberwell Space at Camberwell College of Arts in Peckham Road, London, today opens Moving the Image: photography and its actions, curated by Duncan Wooldridge (*1981), and running until June 1, 2019.

Wooldridge has long meditated on the nature of the photograph through his artworks themselves, such as Expose (2006), a visual oxymoron; a transparent 35mm film cassette loaded with exposed and developed film. Other works highlight its relation to art and its reproduction through photography. He lectures in the medium at the Camberwell College of Arts and has also produced essays and curatorial projects including the provocative Anti-Photography of 2011 and a survey in 2014 of John Hilliard‘s own investigations into photography, by photography. The exhibition catalogue contains his comprehensive essay outlining the rationale for his choice of photographers for Moving the Image, but for my purposes, there is one image that encapsulates many of the ideas behind this selection of works.

Corinne Vionnet‘s Automated Matterhorn, 2013- 17, is an example of the way that the camera has been developed to automatically collect images, moving the agency from the hands of the photographer if, indeed, we can say there even is one.

The pictures in her series come from a web cam. That the originals, before Vionnet ‘captured’ them, could be viewed in almost real time remotely via the web, that they existed simultaneously and virtually anywhere and everywhere, entails an exponential relocation; that is another manifestation of the ‘moving’.

Vionnet’s Matterhorns furthermore introduce some curious ambivalence around the term used by Wooldridge in his catalogue essay—’static’. Usually it means ‘still’ in the sense that photographs are ‘stills’, and in the German stille, are silent. And yet ‘static’ also means ‘noise’ or interference, especially that generated in transmission, of radio waves or digital data, and whether of sound or vision. This is what we see in Vionnet’s representations of a view, from the east, of the peak that straddles the Italian and Swiss borders. Its distinctive profile is familiar as the logo for a distinctively shaped chocolate bar, and from numbers of epic mountaineering movies. The web camera’s fixation on the peak has ‘burnt’ the image of the static form into its sensor so that it produces static in its shape even when the mountain is obscured by clouds and fog.

Repetition moves an image from one material presence to another. It may be by distance transmission as in the case of Vionnet’s Matterhorn, or by propagation, which is how David Horvitz‘ Mood Disorder rematerialises. The image is a cliché self portrait of the artist with his head in his hands with the foam of crashing waves hanging in the air above him. The pose, he says, reprises Dutch/American conceptual artist Bas Jan Ader‘s I’m too sad to tell you of 1970–71.

Horowitz uploaded his picture on Wikimedia Commons, and linked a Wikipedia page on mood disorders to it so that it appeared in the article. The image was picked up by others and began to circulate widely in the form of a copyright-free ‘stock photo’, appearing on over a hundred websites as an illustration in articles on mental health. Taking copies of these uses of his picture which he discovered through a reverse image search, in 2015 Horowitz constructed a 72-page book Mood Disorder, with a text by author Ed Steck (The Garden: Synthetic Environment For Analysis And Simulation and An Interface for a Fractal Landscape), co-published by Chert and Motto Books, Berlin.

Editors on Wikipedia became suspicious of Horowitz’ purpose in uploading the image and online discussions began that considered it self-promotion and Horowitz was banned from editing Wikipedia and the image removed. However, it continued, and presumably continues, to circulate.

The fugitive quality, and the atomised oscillation, of Vionnet’s imagery resonates in two photo-collages by Edouard Taufenbach (*1988, France), L’inconnu du Lac, and Au Jardin, both 2018. His photographs are second-hand, of unknown origin, and thus already dis-placed, and at a re-move from the actual photographer (my hyphens point to the idea of Moving the Image). Not only that, but the photographs are not in Taufenbach’s possession but are from a collection of anonymous images that the director Sébastien Lifshitz has gathered over several decades. These provided Taufenbach with a source of vernacular photography more coherent, stronger and rarer than those he had so far appropriated. These two photographs of leisure, pleasure and homoerotic desire, celebrate the freedom of the body in intimacy and in contact with nature, especially at the water’s edge.

For Au Jardin Taufenbach sliced 45 repeated parts from copies of his selected image of a pale, slight young man seated in hard sunlight on a stone amongst the pebbles of a garden. There is an adamantine urgency in his intense gaze that is locked on the camera lens. Of that we are provided a repeated view, not unlike that which we would experience in a stereo pair, but for emphasis here rather than 3D effect. His doubled face is bracketed by repeats of his shoulders. His chest and crotch are also duplicated. The hand he places firmly on a thigh that thrusts toward the camera is given six iterations. The bulges of flesh at his knees we see four times. A notable effect of the experiment is that though elements of the garden, the ‘ground’, are also repeated like the figure, unlike the figure they become but abstract pattern.

That speaks to the way Taufenbach emphasises human visual cognition. His images replicate the saccades (French for ‘jerks’) that our eyes exercise as they scan a scene. They are not consciously registered, but build comprehension of the image in stages. Even if the image is a ‘still’, the eyes do not regard it statically but rove around, fixing on specific stimuli and connecting them, so that to the eye the image is constantly moving. Taufenbach’s slices and repetitions replicate a physical process that is the basis of visual cognition, as if directed by the very desire that motivated the original, unknown photographer.

Taufenbach might have easily produced his montages with digital means, but chooses a laborious collage process instead, precisely cutting and pasting the tiny slices on sheets of Canson drawing paper. If photography were not eminently repeatable, as it has been since the development by Henry Fox Talbot of the negative/positive process, then its repetition would require such re-making as Taufenbach undertakes, and that is also true of the ‘proto-photographic’ photogram or the rare luminogram which is the medium of choice of another exhibitor, Steff Jamieson (*1988, U.K.)

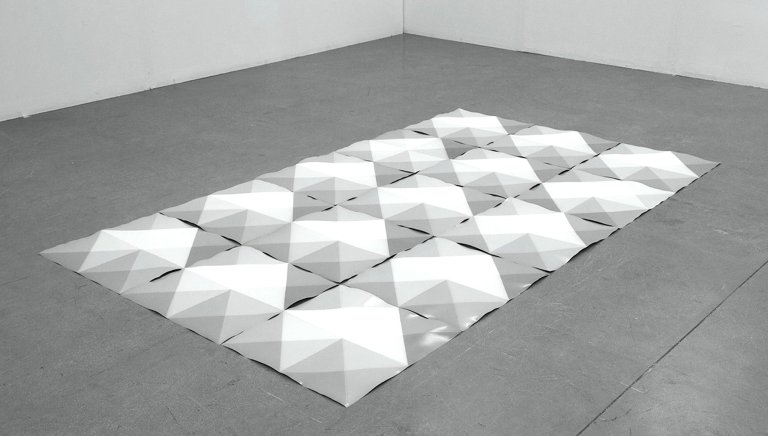

Jamieson’s Habitual Labour II is especially apposite to the thesis of this exhibition, both in its title, which indicates the repetition and the manual work involved. By strategically folding square sheets of photographic paper in a consistent sequence and then exposing each with precisely timed durations through the folds, a multiplication formula emerges. Unfolding the work on the floor and leaving the folds made still apparent, a tessellation of units, not unlike a hand-laid Carl Andre sculpture, asserts its mathematical sculptural physicality, but retains traces of a photographic illusionism.

In the installation, in front of Triangle (Adjusted to Fit) a photograph of mid-century American minimalist works which Louise Lawler, has stretched to fit the Camberwell Space gallery, Jamieson’s work underscores Lawler’s’s distortion of other cubic forms (Donald Judd’s wall sculpture and Sol Lewitt’s floor work) and triangle (Frank Stella); a photo-operative and gestural ‘moving’. Also, the motive elasticity of both Lawler’s and Jamieson’s works is achieved through time, in the exposures and placing of the photogram and the blurring of the art lover’s foot.

It is the masterful curatorship of this exhibition that makes connection both between images by quite different artists, and the adjacency of selected works by single artists, that leads to novel understandings of ‘moving’.

Like Lawler, John MacLean uses digital tools to manipulate elements in his 2019 series Outthinking the Rectangle; images drawn from apparently mundane observations of the urban real. Wooldridge has paired Slip and Ladder so that the cut-and-paste dis-placement and suspension of the blank painted rectangle in the first seems to transfer to its companion image in which, as for several for in his series, MacLean, as illusionist or geometer, makes the white margin of the print ambiguous. Along the way, between these paired images, the rectangle, seen at an angle, shifts from perspectival form into a flat rhombus, then, at almost the same diagrammatic scale, is transformed into one plane of a solid cube against which a ladder stands that ascends into solid blackness or descends into a white abstract void. In the exhibition the rectangles of Taisuke Koyama‘s UNTITLED (RN) hang opposite, seemingly endless flowing rolling copies of his video of light on moving water, rendered in the digital language of RGB.

Moving The Image thus presents contemporary photography in a state of flux that belies the binary distinction of moving or still by conceiving of it as a result of processes of production and pathways of dissemination that challenge conceits of authorial ‘artistry’, yet through action, performance, or interference, also deny its ‘innocence’ as an immutable document.

That understanding hovers over the exhibition between a video and an altered photograph, both by Clare Strand. Her peepshow Material (2015) reveals a video of sunlit dust motes circulated by Brownian motion in the air in her bedroom; microscopic dust which is the bane of the photographer when it is magnified through their processes. In digital photography its re-moval (again the hyphen) is much simpler than the laborious ‘spotting’ with dye and fine brush on a silver gelatin print, and is merely a matter of directing the retouch tool, which appears as a small circle on the screen, over the offending mark so that ‘smart’ software obliterates it from any future print. Strand perversely repeats this digital process on a conventional bromide print by attacking each spot with a hammer and punch and in the process obliterates the image.

There is a resonance in the presence of the video seen through a circular spy hole and the round punch holes that pepper her print, just as there is a resonant relation between the 21 works displayed to enlighten the notions of Moving the Image.

Apart from the above, artists in the exhibition also include: Lou Cantor, Liz Deschenes, Discipula collective, Kensuke Koike, Salvo collective, Dayanita Singh, and Dafna Talmor and includes a special performance of Sarah Pickering’s Reverse Pickpocket and Pickpocket Workshop, originally commissioned for Manifesta 11, Zurich, in 2016.

The exhibition was accompanied by a teaching symposium on 17 April 2019 at Camberwell College of Arts exploring current and future practices in teaching and learning in fine art photography with keynote presentations by Duncan Wooldridge (Camberwell BA Fine Art Photography Course Leader) and writer and curator Emma Lewis (assistant curator at Tate Modern), alongside a variety of short workshops.