“I am never satisfied that I have handled a subject properly until I have contradicted myself at least three times.”

“I am never satisfied that I have handled a subject properly until I have contradicted myself at least three times.”

So proclaimed the influential English critic John Ruskin, born on this date in 1819 (†1900), who at first regarded photography a valuable artistic aid and used the medium himself but by the end of the 1860s, dismissed it as mechanical and incapable of being art at all.

He first became aware of its potential in researching for his book The Stones of Venice 1845 when he was in Venice. There, Ruskin remembers in his autobiography Praeterita (1885–89), he found…

a French artist producing exquisitely bright small plates which contained, under a lens, the Grand Canal or St Mark’s Palace as if a magician had reduced the reality to be carried away into an enchanted land. The little gems of pictures cost a Napoleon each; but with 200 francs I bought the Grand Canal from the Salute to the Rialto; and packed it away in thoughtless triumph.

In a letter to his father from Venice on 7 October 1845 he had written even more glowingly of the new medium;

Daguerreotypes taken by this vivid sunlight are glorious things. It is very nearly the same thing as carrying off the palace itself: every chip of stone and stain is there, and of course there is no mistake about proportions. . . It is a noble invention – say what they will of it – and anyone who has worked and blundered and stammered as I have done for four days, and then sees the thing he has been trying to do so long in vain done perfectly and faultlessly in half a minute won’t abuse it afterwards.

In both cases he appreciates the power of being able to ‘carry away’ a palace ‘to an enchanted land’. Furthermore, in another letter home on 15 October 1845, any doubt about the machine-made nature of such images being a fault is denied. Instead, he writes

…among all the mechanical poison that this terrible 19th. century has poured upon men it has given us at any rate one antidote – the daguerreotype. It’s a most blessed invention, that’s what it is.

His reliance on what he ‘carried away’ for his drawings of architecture is clear. The drawing and steel etching were made, copied, from the daguerreotypes that he commissioned or had made for him by his manservant, or which he eventually started taking himself. For the naysayers amongst art historians who cannot believe that great artists would use a lens in making art, the fact hat he copied them in making his drawings and watercolours can be verified; daguerreotypes reverse the subject like a mirror (unless a mirror was used in making them, as was sometimes done), and Ruskin’s pictures repeat this reversal which he would not had he worked from the original subject.

Ruskin was a well-practiced and obsessive artist, motivated in his early work by a need to impress his parents (who were very close and traveled with him in Europe). Using and making daguerreotypes may have influenced his move from the style (left, below) of Samuel Prout (1783–1852), one of the masters of British watercolour architectural painting, to a more ‘truthful’ style of painting based on intense observation of nature, and one which influenced the young Pre-Raphaelites whom he championed.

Ruskin visited Venice in 1845 as he worked on the second volume of the five-volume Modern Painters, his The Seven Lamps of Architecture (1849) and the three volumes of The Stones of Venice (1851-53). Venice, which he saw as degenerate and in the process of physical decay, for him represented a moral and social lesson about the relation of art to the society that produced it.

Modern Painters is mainly a defence of J.M.W. Turner whose works he catalogued after the great English artist died and of whom Ruskin, though never considering himself an ‘artist’, became a devotee, taking from him an interest in atmospheric effects and a quite radical realism in his accounts, visual and textual, of the way we see, in the watercolour below manifested as broken passages and variation between tight detail and broad impression.

His concerns reflect shifts in contemporary discourse on visual perception: a complex matrix of ‘truth to nature’, aesthetics, the mechanics of the daguerreotype, and the role of artistic license.

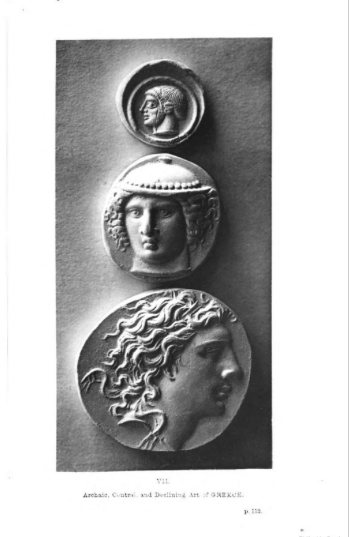

Apart from his publication of them as illustrations (in the form of engraved copies and collotypes) in his numerous books, his collection of daguerreotypes was thought long lost. He adopted the Collotype early, using this dichromate-based photographic process, invented by Alphonse Poitevin in 1856, to illustrate his Aratra Pentelici. Six Lectures on the Elements of Sculpture published in 1872. The beautiful screen-less technique was used for large volume mechanical printing before the advent of offset lithography.

It is almost twelve years since Ken and Jenny Jacobson noticed in the catalogue of the provincial auction house of Farmers’ & Kidd’s in Penrith, Cumbria a listing for a mahogany box with ‘photographs on metal’ of ‘buildings’ and ‘stonework’, their value £80–120. With some background research they shrewdly recognised the 121 daguerreotypes and fourteen salt paper prints as being his forgotten collection documented in Ruskin’s manuscript ‘Coin Book’, a numerical but incomplete listing of his daguerreotype collection held in the Ruskin Library in Lancaster. The numbering in the ‘Coin Book’ correlated with those numbers found on the daguerreotypes for auction. After two minutes, the Jacobsons secured the winning bid of £75,000 [their book Carrying Off the Palaces – John Ruskin’s Lost Daguerreotypes was published by Bernard Quaritch Ltd, London, in 2015].

In all, Ruskin owned at least 233 daguerreotypes, mostly of architectural views and details in Venice and views in the Alps and north-western France, and though modest in comparison with others’ collections, Ruskin put his to best use in his lectures, exhibitions and books…and, comparisons prove, as the primary source for much of his imagery.

When in 1859 he visited Freiburg, he made the following daguerreotypes which are the source of a watercolour sketch (at top, below) in which he now incorporates the setting of the buildings and places more emphasis on their architectural and structural relation with each other.

In his writings Ruskin recommended photography to document architecture. He was an active and influential member of the Architectural Photographic Association, formed in April 1857. Even though by the mid-1850s the wet collodion process had become predominant, Ruskin continued to make daguerreotypes until 1858.

However, despite its veracity that was central to his support of Pre-Raphaelite and landscape aesthetics, Ruskin started to revise his high opinion of photography. Was this as a response to the negative-based calotype, which was less precise in its rendering? Was there something about lens-based media that could not achieve the suggestiveness of forms seen in Turner, where the viewer feels that they are seeing more detail than was actually painted?

It was around this time, in 1856, that he becomes ambivalent, identifying artistic affect in some photographs and precision of form in others, but in the same breath complaining of their infidelity in rendering tonality;

Photographs never look entirely clear and sharp; but because clearness is supposed a merit in them, they are usually taken from very clearly marked and un-Turnerian subjects; and such results as are misty and faint, though often those which contain the most subtle renderings of nature, are thrown away, and the clear ones only are preserved. Those clear ones depend for much of their force on the faults of the process. Photography either exaggerates shadows or loses detail in the lights, and, in many ways . . . misses certain of the subtleties of natural effect (which are often the things that Turner has chiefly aimed at), while it renders subtleties of form which no human hand could achieve

Lady Elizabeth Eastlake (1809–1893), his contemporary, in her famous essay ‘Photography’ in The London Quarterly Review, No. 101, April 1857, pp. 442-468, echoes such reservations more concisely; she considers that artistic representations require “artistic feeling” to selectively emphasise what was significant, but that photography

for all that requires mere manual correctness, and mere manual slavery, without any employment of the artistic feeling, she is the proper and therefore the perfect medium.

Charles Baudelaire (1821–1867) in his 1859 Salon review more sternly warns that if photography;

…be allowed to encroach upon the domain of the impalpable and the imaginary, upon anything whose value depends solely upon the addition of a man’s soul, then it will be so much the worse for us!

Ruskin demonstrates reasons for his hesitations about photography through this illustration which is repeated more than once in his publications.

The other day I sketched the towers of the Swiss Fribourg hastily from the Hotel de Zahringen. It was a misty morning with broken sunshine, and the towers were seen by flickering light through broken clouds, dark blue mist filling the hollow of the valley behind them. I have engraved the sketch on the opposite page, adding a few details, and exaggerating the exaggerations; for in drawing from nature, even at speed, I am not in the habit of exaggerating enough to illustrate what I mean. The next day, on a clear and calm forenoon, I daguerreotyped the towers, with the result given on the next plate (25 Fig. 2); and this unexaggerated statement, with its details properly painted, would not only be the more right, but infinitely the grander of the two. But the first sketch nevertheless conveys, in some respects, a truer idea of Fribourg than any other, and has, therefore, a certain use. For instance, the wall going up behind the main tower is seen in my drawing to bend very distinctly, following the different slopes of the hill. In the daguerreotype this bend is hardly perceptible. And yet the notablest thing in the town of Fribourg is, that all its walls have got flexible spines, and creep up and down the precipices more in the manner of cats than walls ; and there is a general sense of height, strength and grace, about its belts of tower and rampart, which clings even to every separate and less graceful piece of them when seen on the spot; so that the hasty sketch, expressing this, has a certain veracity wanting altogether in the daguerreotype.

Ruskin’s emerging belief was that the infallibility of the photograph was ‘impious’, as what he admired in painting, fastidious naturalism, he came to despise in photography. To understand that, it should be seen in relation to his conviction that a painting, while it should try to perfectly copy nature, is and should always be, ‘imperfect’ in order to emphasise that it could never compete with reality, to “make itself poor to exalt its theme”;

You may think that a bird’s nest by William Hunt is better than a real bird’s nest. But it would be better for us that all the pictures in the world perished, than that birds should cease to build nests, And it is precisely in its expression of this inferiority that the drawing itself becomes valuable. It is because a photograph cannot condemn itself that it is worthless. The glory of a great picture is its shame; and the charm of it in expressing pleasure of a loving heart that there is something better than pictures.

William “Bird’s Nest” Henry Hunt (1790 – 1864), the English watercolour painter to whom he refers is not William Holman Hunt (1827 – 1910), one of the founders of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood whom Ruskin also championed, but in their case too, Ruskin is ambivalent about the value of photography, urging them to…

adhere to their principles and paint nature as it is around them, with the help of modern science…they will…found a new and noble school in England.

That what he meant by ‘modern science’ was photography is especially made clear in another of his texts of 1851, in which Ruskin regretted that

artists in general do not think it worth their while to perpetuate some of the beautiful effects which the Daguerreotype alone can seize.

But in his Edinburgh lectures of 1853 he recants and issues a complete denial of any notion that the Brotherhood worked from photographs;

When…it began to be forced upon men’s unwilling belief that the style of the Pre – Raphaelites was true and was according to nature, the last forgery invented respecting them is, that they copy photographs. You observe how completely this last piece of malice defeats the rest. It admits they are true to nature, though only that it may deprive them of all merit of being so. But it may itself be at once refuted by the bold challenge to their opponents to produce a Pre-Raphaelite picture, or anything like one, themselves copying a photograph. Pre-Raphaelitism has but one principle, that of absolute, uncompromising truth in all that it does, obtained by working everything, down to the most minute detail from nature and from nature only

William Bell Scott (1811–1890), the painter, poet friend of Rossetti, insisted however that;

the seed of the flower of Pre-Raphaelitism was photography. History, genre, medievalism or any poetry were allowable as subject but the execution was to be like the binocular representations of leaves that the stereoscope was then beginning to show.

Though you will find it rarely mentioned in the ever-popular publications on the Pre-Raphaelites, they embraced the camera image as a means to gather the intense visual data on which they depended for their realist imagery. A good example is John Everett Millais (1829 – 1896), whom Ruskin vigorously supported but came to loathe because of his marrying Effie only a year after she had filed her suit of nullity against Ruskin on grounds of “non-consummation” in April 1854.

Loath too are historians of painting to admit the ‘infidelity’ of artists using optical aids (witness their furore after David Hockney suggested such blasphemy), but there are numerous evidences of each of Millais’ fellow Pre-Raphaelites using the medium; Holman Hunt clearly consulted photographs made by James Graham (1806–1869) on their trip to the Holy Land in 1854; Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828–1882) owned many photographs of Jane Morris and on two well documented occasions he painted over photographs, Ford Madox Brown (1821–1893) had daguerreotypes made ‘to save time’; Edward Burne-Jones (1833–1898) and William Morris (1834–1896) posed a model in a suit of armour, ‘to be photographed in various positions’; in commissioning photos by Beatrix Potter’s father Rupert Potter (1832–1914), Millais can be seen to rely heavily on them as reference (below);

Though he warns against slavishly copying the falsity of its tonal rendition with blank skies and black shadows, ultimately, Ruskin’s argument with photography is ideological, religious even, rather than technical. Clearly still in love with its veracity, his condemnation centres on it as just another “mechanical poison that this terrible 19th century has poured upon men”, part of the industrialisation of the country that he saw destroying the divine glories of nature. His sentiment became increasingly vehement as he became more affected by the mental instability that intensified in his later years.

He regarded the photographer as unable to generate artistic ‘suggestion’ or to interpret the subject. He would no doubt have felt vindicated to see the attempts of the Pictorialists who succeeded him to fail in their attempts to make photography like painting. He may have been more enthusiastic about the f64 Group and their truth to medium, but while he might understand our current obsession with the ‘misty and faint‘, wouldn’t he be utterly puzzled by contemporary fine art photography? We cannot tell and it is futile to guess. His own photographs and his mind are fixed in the nineteenth century.

An amazing piece James – some time ago I encountered a similar thread of Ruskin’s love of photography and then his change of heart … your research and writing has given the topic the full measure that it deserves…

LikeLike

Thank you Vicki and Doug for your kind comments. Your Photobook Compendium looks to be a valuable contribution to cross-Tasman photobook scholarship. I’ll make sure news of it gets around!

LikeLike