September 21: In discussing a painting we may speak of facture, which might translate as its ‘making‘, the direction, density and lubricity of applications of paint by the brush which, whether overt or subtle, are layered on, or in, the canvas or board to be inspected and appreciated forever.

September 21: In discussing a painting we may speak of facture, which might translate as its ‘making‘, the direction, density and lubricity of applications of paint by the brush which, whether overt or subtle, are layered on, or in, the canvas or board to be inspected and appreciated forever.

A sculptor’s materials are carefully selected for their suitability to the idea, whether they be a row of bricks on a gallery floor, chiselled and polished marble, or bronze cast seamlessly, from a wax over wood and wire armature, in a complex, hazardous process that transforms the malleable, fragile substance into hard metal that reproduces detail as fine as a fingerprint.

But where is the ‘surface’ in photography? When printed, is it the paper? Does that surface betray anything of the ‘making’ of the photograph; its facture? The principle of the latent image, which is ephemeral and fleeting, would apparently deny any such possibility. The image is seen and ‘captured’ as evanescent light transmitted momentarily onto a chemical or electronic receptor to ‘develop’ the seen image later through processing. Light has been traced, but what is preserved is the frame surrounding the photographer’s eye.

Photographer Paolo Ventura (*1968) from Italy, engages with the paradox of the ‘photographic surface’, doing so from an impulse somewhat different from the fin-de-siècle Pictorialists, who as the name of this international trend implies, sought to make photographs into ‘pictures’, in the sense implied in the origin of ‘picture’ in late Middle English from the Latin pictura; ‘painted’ (from the verb pingere).

Theirs was a desire succinctly expressed by A. H. Hall in his 1896 book Artistic Landscape Photography (London; Percy Lunn & Co. Ltd., pp.26-7);

In the early days of photography a photographer never thought it worth his while to point his camera to any object that had not some particular interest connected with it […] Whereas in former times the photographer’s aim was to produce a representation or a portrait of a particular scene, that of the modern photographer is to produce a picture.

Pictorialists desiring a ‘painterly’ appearance resorted to the revival and reinvention of the bromoil, carbon print and gum bichromate, all derived from Alphonse Louis Poitevin‘s discovery of the light–sensitive properties of bichromated gelatin in the 1850s, and platinum prints (made first by John Herschel and Robert Hunt in 1832 and patented in 1873), that enabled, or required, the interference by the photographer in ‘making’ the print. However, the process was quite the reverse of painting since it requires the printer to rub back selectively into the pigmented emulsion to retrieve details, or to decide to leave them obscured.

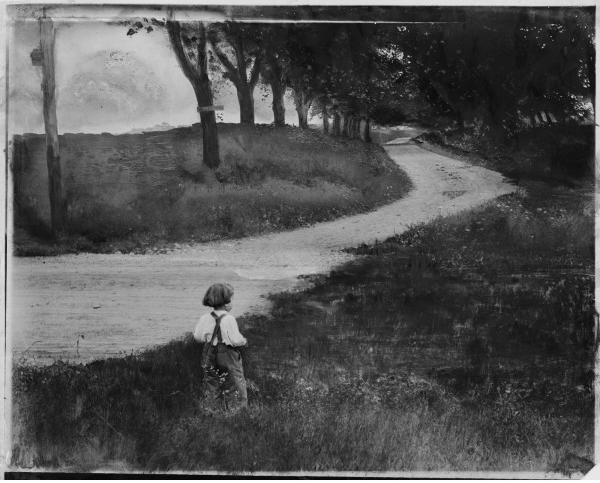

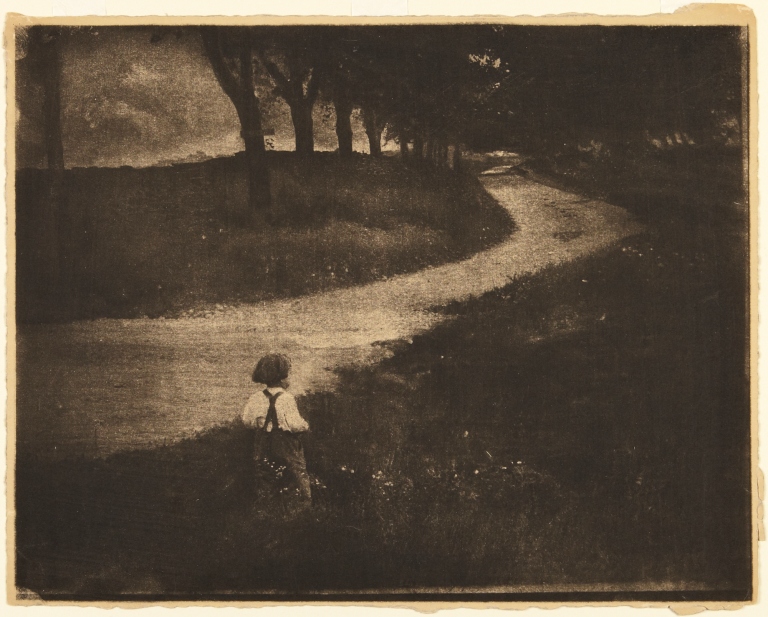

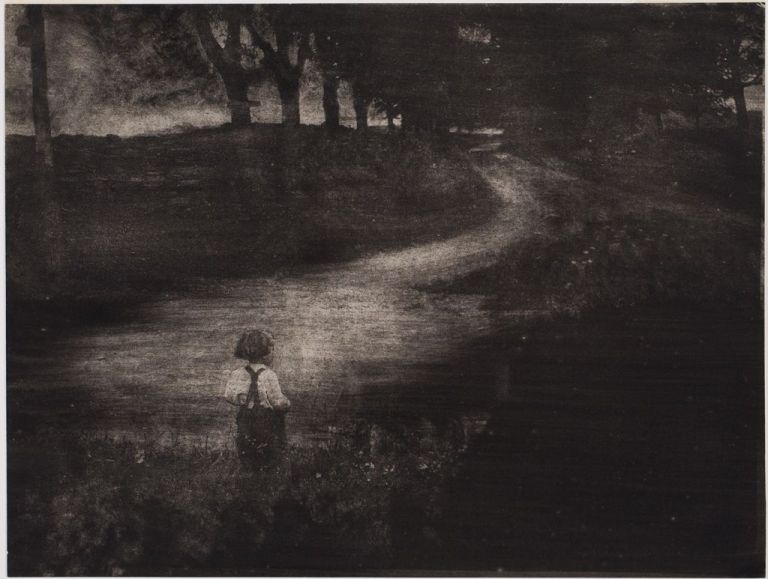

Gertrude Käsebier (1852 -1934) provides a typical example. The manipulation of the original negative through these printing techniques produced ‘unique’ prints, unable to be repeated exactly, just like a painting from a sketch. The ingredients of her Road to Rome of 1903, are a country road and a small boy, seen here with his aunt in a platinum print.

![Gertrude Käsebier Hermine Kõsebier Turner and her Nephew Charles [Family - sale catalogue, 2007] 1903 (ca) Platinum print 5 3:4 x 8 1:8 in (14.6 x 20.6 cm)](https://onthisdateinphotography.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/gertrude-kc3a4sebier-hermine-kc3b5sebier-turner-and-her-nephew-charles-family-sale-catalogue-2007-1903-ca-platinum-print-5-34-x-8-18-in-14-6-x-20-6-cm.jpg?w=768)

The boy is set in ever more moody Symbolist evocations of his future (“all roads lead to Rome”) through her heavy manipulations of another shot from the same time, in a variety of techniques including painting on a sharply focussed straight gelatin silver print through a platinum version, to a series of gum bichromate renderings in ochre- and umber-coloured pigment.

It is easier to obtain images of such one-off Pictorialist prints in various ‘states’ and media such as these by Käsebier above because she was American and an associate of Alfred Stieglitz, exhibiting at his Gallery 291.

However it should be acknowledged that such prominence does not mean that the American Pictorialists are exclusively the best, nor were they the trend-setters. It was an international style and in Italy, the home of Paolo Ventura whose show at The Edwynn Houk Gallery 745 Fifth Avenue New York Ny 10151 is opening today and runs until 11 November 2017, Italian Pictorialists including Griva (1882 – 1962), above, the earlier Guido Rey (1861–1935) and Cesare Schiapparelli (1859-1940), Enrico Grosso, Luigi Cavadini (1878-1962) amongst others, competed as equals with other virtuoso European and American photographers participating at the various international Salons of artistic photography.

Ventura describes his working process;

…the process I use for all of my work […] consists of re-creating the story I want to tell using models and built environments. The use of models allows me the freedom to create anything I want–to make images exactly as I imagine them.

My work is divided into three phases. The first is total freedom; this is when I am able to imagine what it is I want to represent. During this time I often sit down and sketch what I see in my mind in order to give shape to a blank canvas.

The second phase is the creation of the set – a manual activity. I can take from one day to one month to build a set depending on the complexity of the scene. Not just the technical complexity of the building it, but getting the feeling of the scene just right.

The third phase is the actual creation of the photograph. I start by taking a Polaroid and adjusting details of the set until it’s absolutely perfect. I often carry a Polaroid around in my pocket for a day or more to think about it. Once I am completely happy with the image I shoot film. This is the most important and the least important ‘act’ of the process.

I use photographs because what people see in photographs they believe is real – even if they know it is a model. When you go to see a film you know its a setup, but you cry, you get excited, you are deeply touched. People want both believe what they see on film.

Though his imagery is constructed, he has a different purpose in mind from that of the Pictorialists. His imagery derives from his childhood experience of “a father not going to an office, but staying at home, drawing…it authorised me just to think, to be fantastical, creative, not just for fun, but for work. It was really a magical youth.”

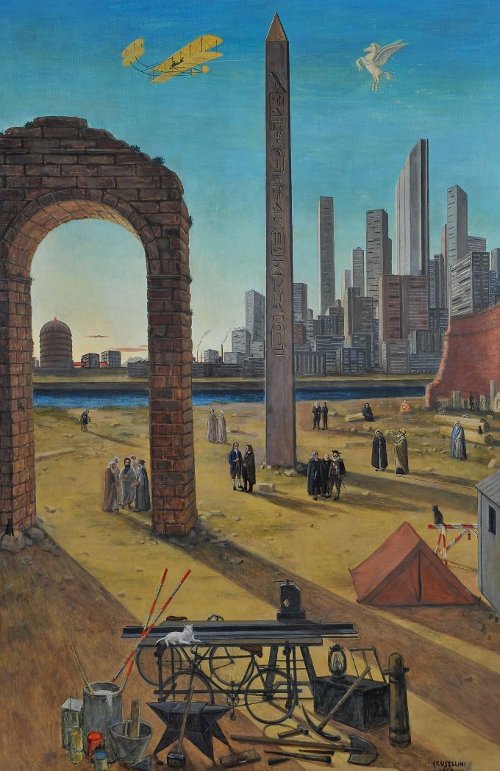

He was the son of a celebrated Italian children’s book illustrator of the 1960s and 1970s and, perhaps through his father, taps into Italian mid-twentieth-century Pittura Metafisica artists such as Carlo Carrà (1881-1966) and Gianfilippo Usellini (1903–1971), and fifteenth-century early Renaissance painting, particularly that of Piero della Francesca (c. 1415 –1492), and through them, I would argue, can be compared to Ben Shahn (1898–1969).

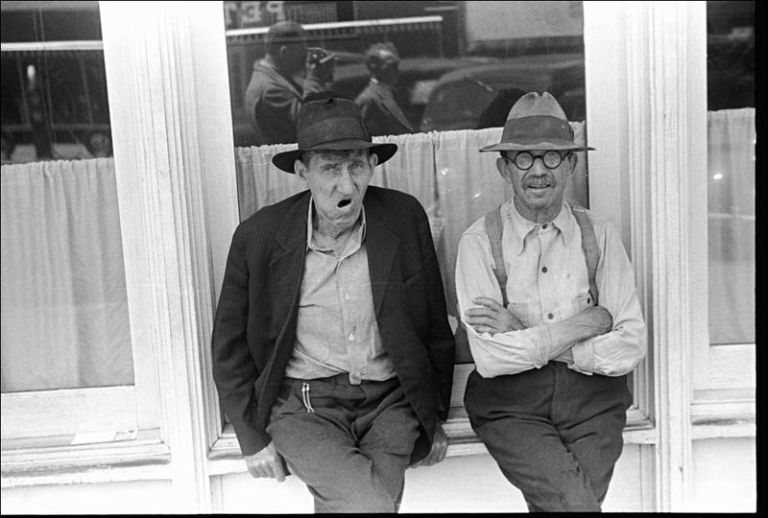

Ben Shahn claimed that he had “never taken a picture for photography’s sake, but always for my own use” and that photography “is a mind, an eye, but not an art”. In fact, he left over 5000 photographic prints when he died, having learned the medium from Walker Evans, with whom he shared a studio in Greenwich Village in the early 1930s. He asked his brother to buy him a second-hand Leica and with it took pictures of immigrants, unemployed workers and homeless people on the Lower East Side and other parts of Manhattan, and prisoners in the state of New York. He documented artists’ strikes and parades, this being during his most active period politically. From 1935 to 1938 Shahn photographed for the RA/FSA, contributing to their campaign to publicise the plight of the rural poor.

His pictures were left out of his “artistic estate” by appraisers, who deemed the pictures worthless and fortunately Harvard University mounted a first showing of them in 1969 prompting his grateful widow to donated his entire photographic collection to Harvard’s Fogg Museum in 1970. They provide us with an insight into the role of photographs in his painting and they way they inform his compelling social realism.

A strategy he used in order to get realistic portrayals of social conditions was to attach a right-angle eyepiece to his rangefinder Leica, originally designed to facilitate copy-stand photography but which many street photographers employed for candid shots. He depicts himself using it in the above rather Thurberesque cartoon dedicated to ‘Roy’ (Stryker) who, during the Great Depression, headed the Information Division of the Farm Security Administration (FSA) and deployed its documentary photographers, and who, Shahn’s inscription continues, “made it possible for me to work uninterrupted for 3 years…”

In his 20s, to free himself from his academic training in New York, Ben Shahn had spent a month in Italy and four months in Paris, with shorter periods in North Africa, visiting museums, talking with other artists and eagerly painting and reading as he went. In particular he was impressed in Italy by the vivid language of murals, and especially those of Piero della Francesca who is also a favourite of Paolo Ventura.

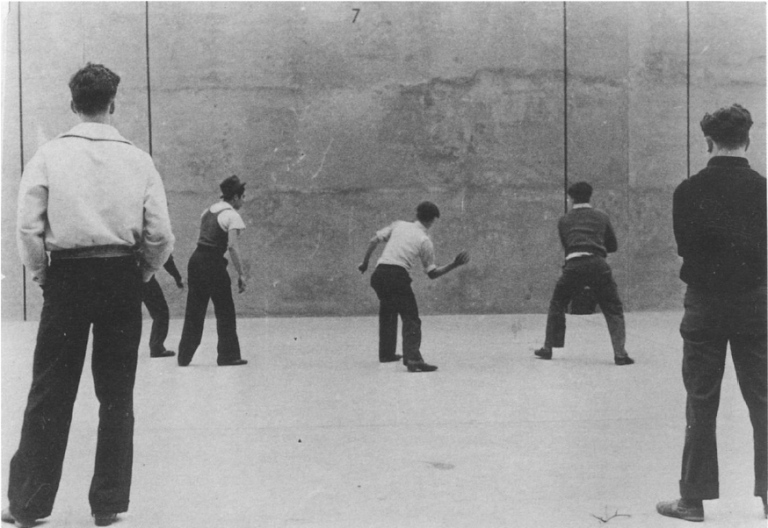

His untitled photograph of handball players was made around 1933 just after he took up photography and before his period as a FSA photographer. It has striking symmetry rarely achieved amongst the random events of the street.

To make the painting of the scene six years later, Shahn transcribes the positions of the handball players including the photographic accident of a tensed arm and leg that sprouts from the bomber jacket of the man at left, but he spreads the men away from each other and expands the frame to break the symmetry and to include a brownstone over the top of the wall, and to encompass also a billboard at left. Gestures and poses are exaggerated and a hand is added to the figure at right which is cropped in the photograph. The line markings on the wall are made to converge to further stretch the space. In a 1957 interview, Shahn described his painting as being about “social relationships”.

Following Shahn’s 1947 retrospective at MoMA and his representation of the USA at the 1954 Venice Biennale, criticism of him became negative. Clement Greenberg, though admitting that Handball had exerted a “shock”, as an ex-Trotskyite reacted against Shahn’s socialist agenda as “essentially beside the point as far as ambitious present-day painting is concerned” and “derivative”, describing him as “more naturally photographer than painter”; while Barbara Rose‘s book American Painting briefly dismisses him as one of the ‘Ashcan School’ who aspired to make “paintings as great as those of the Renaissance” by attempting “to use Renaissance techniques like tempera.” “Unfortunately,” she concludes, “all they usually achieved was a pastiche of the styles of the past.”

To regard Handball as both painting and photograph, to see them as an amalgam of the two media, as a synthesis of an observation of society made with honest realist intentions with the iconic directness and vehemence that we see in a Fra Angelico or Piero della Francesca, is to understand, at least in part, what Paolo Ventura achieves.

All three artists emphasise hand gestures to convey emotional affect and respectfully set their figures back into geometric architecture, while Shahn’s and Ventura’s reference to Early Renaissance painters endows the subjects of their narrative with a secular beatification. The painters of the Quattrocento were grappling with a photographic space created by their application of newly discovered rules of perspective and had to find ways of accommodating events in space that their predecessors had depicted previously in-the-flat with simplified iconic figures and forms. Is it that they are dealing with similar narrative communication over a paradigm shift in media that makes these artists of interest to Shahn and Ventura?

In Paolo Ventura’s pictures characters including lovers, soldiers, and jesters appear and reappear and are often played by family members, including his graphic novelist twin brother Andrea, his son Prima, his wife who is designer Kim Mingo, and himself. This dramatis personae plays out a dreamlike narrative that evolves through his frequent exhibitions.

Ventura graduated from Milan’s Accademia di Belle Arti in 1991 and spent ten years photographing fashion before: realising “there was no life, no story in anything I was making,” and consequently moved to Brooklyn in 2001 where he began constructing dioramas; “What I was seeing in the diorama,” he says, “was exactly what I had in my mind, and that made me very happy.”

His first series, War Souvenir (2005) is based on his grandmother’s wartime memories. This was followed by The Automaton (2010) which eerily sets Pinocchio in a Jewish ghetto in 1943. From 2011 he has used Photoshop in the construction of his tableaux. He enthuses;

Digital technology has opened the door of fantasy and imagination. Its like being a painter and someone gives you a bag and inside there is a completely new colour.

In the new Edwynn Houk Gallery show Eclipse, he goes back to manually collaging his digital prints and adding textured overpainting, in a manner that creates a tangible facture.

Ventura achieves visually, though his set-building and sliding-together of photography and painting, the kind of elision that we find in song, in which we experience a the sound of speech and music at once that lure us into a narrative that forms inside us.

Love Ventura’s work and your commentary James 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for your kind comment Marcus!

LikeLike