February 10: What happens when photography moves from the territory of reportage to that of myth?

February 10: What happens when photography moves from the territory of reportage to that of myth?

The Ian Potter Museum of Art at the University of Melbourne, Australia is exhibiting All the Better to See You With: Fairy Tales Transformed until March 4.

The show features works by Broersen & Lukács, Kate Daw, Peter Ellis, Dina Goldstein, Mirando Haz, Vivienne Shark Le Witt, Amanda Marburg, Tracey Moffatt, Polixeni Papapetrou, Patricia Piccinini, Paula Rego, Lotte Reiniger, Allison Schulnik, Sally Smart, Kiki Smith, Kylie Stillman, Tale of Tales, Janaina Tschäpe, Miwa Yanagi, Kara Walker, and Zilverster (Sharon Goodwin and Irene Hanenbergh).

Of these Dina Goldstein (*1969), Tracey Moffatt (*1960), Polixeni Papapetrou (*1960) and Miwa Yanagi (*1967) show photographs. This presents us with the spectacle of our ‘literal’ medium entering the “imaginary territory” of which Marina Warner writes in her 2014 Once Upon a Time: A Short History of Fairy Tale, as quoted at the head of curator Samantha Comte’s essay in the catalogue;

Fairy tales report from imaginary territory – a magical elsewhere of possibility; a hero or a heroine or sometimes both together are faced with ordeals, terrors, and disaster in a world that, while it bears some resemblance to the ordinary conditions of human existence, mostly diverges from it in the way it works, taking the protagonists – and us, the story’s readers or listeners – to another place where wonders are commonplace and desires are fulfilled.

Warner’s use of the term ‘report’ is germane as we are already used to news photography reporting unimaginable events from otherwise unknowable places, but excursions and exertions different from but equivalent to those of the photojournalists must be made by each of these photographers to create ‘a magical elsewhere’ in order for us to see it; a different effort from that which the painters, videographers, installation artists, sculptors, animators, printmakers and gamers also in the show must make.

Dina Goldstein was born in Tel Aviv and emigrated to Canada at age seven. After completing studies in history and photography in Vancouver in 1993 she began a career in photojournalism and from 2000 she was on commission for magazines and advertising agencies. She showed her reportage Images of Gaza in 2001, so it is she that most vividly represents passage of photography from realism into this ‘magical elsewhere’. The result is black humour, an undeniable ingredient of the original fairytales.

The Ian Potter shows her first large scale tableau series Fallen Princesses (2007-2009) which transports us into suburbia to discover Disney princesses in the wash-up of ‘happily ever after’. Cinderella consoles herself with a Jack Daniels in a seedy bar, a victim to the unwanted attentions of the barflies. Snow White discovers her dwarves transformed into wailing babies and pestering toddlers, while her disenchanted ‘prince’ occupies himself with horse racing on TV and a can of beer.

Princess Pea finds herself on a stack of discarded mattresses in the town dump, and in work not exhibited here, Rapunzel’s lustrous ladder-length locks have fallen to her cancer chemotherapy, and the young Sleeping Beauty is discovered by her now aged Prince in a nursing home.

Goldstein’s background in advertising and editorial work, and her consequently professional handling of lighting, staging and digital processing, enable her to lend fairytale hyperbole to failed dreams, the conceit of eternal youth, parenthood, mental breakdown and substance abuse, environmental and a myriad other disasters in gaudy widescreen.

These are the textures and colours of the marketing and commercialisation that brand the Walt Disney versions, his sugary, glitzy and ultimately facile take on tales intended originally to have cautionary impact, not his cliché and sexist escapism. Goldstein’s princesses find that they cannot escape their fates, sealed as they are in the constraints of contemporary political, socio-economic, environmental and gender realities.

Polixeni Papapetrou is also a celebrated photographer, one of several Australian artists in this show which gives due prominence to them amongst internationals. Her long-term and developing interest in the fairytale came through her children Olympia and Solomon and from her own early documentation of drag queens and Elvis impersonators.

Curator Naomi Cass relates Papapetrou’s recollection of an early game instigated by Olympia, that of playing the story of Pocahontas of the 1995 Walt Disney animation, although, as Papapetrou remembers, Olympia declared, ” I don’t want to play Pocahontas, I want to be the brave.” Her daughter’s insistence emphasises the self-identification that the traditional fairytales prompt in their listener. They were intended as personal stories that would guide them toward good lives, and the terror that the unexpurgated originals engender warned them away from real evil.

These games helped to inspire a series of pantomimes created by the whole family for the camera, with her husband, critic Robert Nelson, painting walk-in brushy tromp-l’oeil story-book backdrops in day-glo colour, and her mother sewing costumes.

Turning to the mythology of her own country, Papapetrou discovered the stories of children lost in the bush which have fascinated us since the days of the early settlers. These are real tales of epic searches, sometimes successful, often times tragic, and even sinister, when squatters, finding themselves down on their luck, were rumoured to have abandoned starving children to an uncertain fate.

In this show, Papapetrou’s most uncanny, and therefore most successful evocation of the mythic realm, is this giddying image based around Joan Lindsay’s 1967 novel Picnic at Hanging Rock which tells of the disappearance of schoolgirls on the monolith that rises above the plains in North-Central Victoria (my home). The confounding, byzantine perspective of the location in flat light creates this effect, but so does the threefold appearance of seemingly the same childish figure in a narrative series of poses that lead toward the viewer; weepily despairing, shoeless, then prostrate. The gaze returns inexorably along the tilting path to the black maw under the hanging boulder.

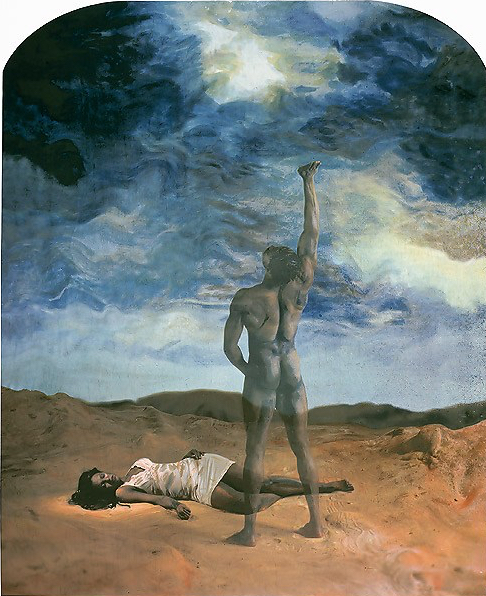

Tracey Moffatt follows the Australian mythological thread into her own indigenous ancestry with Invocation from 2000, but ramps up a cinematic tension. According to Comte’s essay this involves mixing a number of sources from Disney, the Brothers Grimm and Hitchcock. That could apply to any of Moffatt’s productions, and these images have a movie poster aesthetic, a convention which produces imagery that refers to the film narrative in a scene that does not appear in the movie, and we are left to guess the script of this one too.

There is, as always in Moffat’s work, something intriguingly ‘off’ in her artistry, something that troubled reviewers of her outback angst/gangster/gangsta mix in her Venice Biennale show last year, but which is a sign of defiant originality. Here in this much older series it appears in complex photomontage for which she collaborated with a photo-screenprinter over a year to create a palette quite alien to conventional photography. The result looks both painterly and photographic, and would have required multiple layers in order to achieve the range of colour, so that on close inspection a glossy buildup of ink is apparent. The title of the series refers to the act of conjuration, the ‘granting of wishes’, that is familiar from fairytales, but what it entails here, set in a stark landscape, is fearful, portentous and epic.

Also an exhibitor at the Venice Biennale, the 53rd in 2009, with her fierce Windswept Women series, Miwa Yanagi was already, by the mid-90s, acclaimed for reacting against the Japanese stereotype of bijinga (beautiful women pictures). Her discovery came in 1996 when Yasumasa Morimura (*1951) a successful fine arts photographer, used her home as a set and saw her pictures. He arranged to have her exhibit with him in Germany beside Jeff Wall and Cindy Sherman.

She follows an alternative Japanese tradition of the grotesque in femininity, that of Ono no Komachi, the early 9th-century beauty of the Heian Era noh plays who was often portrayed in the guise of an elderly beggar, and of Yamauba, a wild witch living the mountains during the Edo Period (1603-1867). Shinso Okamoto (1894–1933) and Chusei Inagaki (1897–1922) in the 20th century continued this with their ‘ugly’ geishas. We can expect then, that Yanagi’s approach to the fairy tale in her series of that title from 2004 will be challenging.

Against the high colour saturation of her earlier Elevator Girls her choice of monochrome is calculated to be representative of a world of darkness, of dreams and the subconscious. In order to place emphasis on the passage from childhood to adulthood through the teenage years, she subverts the traditional storylines by fusing the young and old protagonists to represent the teenage state as a transfiguration through the simple device of masking their faces.

The result is sinister; the old crone with the body of a child. But it is also a transformation, often a reversal, of the traditional narratives so that we come to understand that the subject is both characters rolled into one. Instead of Gretel proffering a bone for the witch to test how fat she has grown, it is she instead who bites the finger of the witch. Red Riding Hood and her grandmother, who is clearly another child in a mask, both find themselves, covered in gore, in the belly of the wolf which is ominously furnished with a zipper, becoming simultaneously sleeping bag, costume and body bag.

The Little Match Girl is at once the frozen child in the gutter and the grandmother of her dying visions.

Says Comte;

I don’t think I realised how powerful the genre of fairytales is, that it can be really used to assert a dominant narrative within our culture, but also how it can be subverted and have such an impact.

Today the gallery was also the venue for a small conference Fairy tales across the ages 1.00- 3.00pm which was ‘an investigation of fairy tales across the ages from the 17th century to Disney through to modern day screen teens and adaptations’. My partner Lorena Carrington, whose illustrations for Kate Forsyth‘s retellings in the recently released Vasilisa the Wise, were omitted by some extraordinary oversight from the exhibition (as I jokingly suggested to her), attended the forum with Caitlyn Lehmann. She reports that though she can’t recall mention of works in the exhibition by presenters who were keen to relate their own research, the content was enlightening.

Michelle J. Smith, Senior Lecturer in Literary Studies at Monash University, where she teaches fairy tale and children’s literature, asked “why Red and her grandmother suddenly needed a woodsman to save them” to highlight the way that the heroic trickster capability of Red Riding Hood has been denied as the story changed over time. Lorena was impressed especially by the paper by Dr Victoria Tedeschi (English and Theatre Studies in the School of Culture and Communication at the University of Melbourne) who discerned how human agency in environmental degradation is represented in English versions of The Fisherman and his Wife and The Dryad.

Of the connections, and differences, between the text and image of the fairy tale, that each of these photographers have had to deal, Lorena says:

An illustration can capture an essential feeling immediately. A good writer can do the same in a few sentences, but the reader still has to purposefully engage with the text. Once a writer captures their reader, however, they have the luxury of all those words. They can fill in details, delve inside the mind of the characters, tell the reader as much or as little as they choose. Reading is a purposeful act; it’s something you sink into willingly. You give your time to it, and are (one hopes!) rewarded with a rich, detailed and intoxicating experience.

Illustration is immediate. You can explore the image and look for detail, but the first impression is the strongest. I purposefully leave a lot unsaid in my images, and try to leave space for memory and imagination. People often have a very personal response to them. They are taken back to an essential feeling they remember from childhood; it’s often something quite visceral. That’s when I know I’m doing something right.

If you are curious about this huge show and wish to catch it before it closes on March 4th you could do no better than to view Dr Marcus Bunyan‘s comprehensive review which covers every artist exhibited with excellent installation shots by Christian Capurro. He rates the show “Superlative”;

Every piece of artwork in this extraordinary, quirky, spellbinding exhibition (spread over the three floors of the The Ian Potter Museum of Art at The University of Melbourne) is strong and valuable to the investigation of the overall concept, that of fairy tales transformed.

…and…

Simply put, this is the best local exhibition I have seen this year. A must see before it closes.

4 thoughts on “February 10: Fairytale”