Whether by benign or malign intent, panoramic photograph presents a view that is sweeping, all-encompassing; global.

Whether by benign or malign intent, panoramic photograph presents a view that is sweeping, all-encompassing; global.

To continue this series of posts on the subject, here is another approach to the making of panoramas; that of Englishman Thomas Sutton (1819-1875). He who first demonstrated the principle of colour photography, on 28th September 1859, patented a water-filled lens contained in a special camera designed to take curved glass plates seen below in this almost pristine example kept by Museums Victoria.

It is said that he was inspired by seeing novelty snow globes — or was it the form of the human eye?

His was the earliest panoramic wide-angle lens, ingeniously comprised of a pair of glass hemispheres in brass mounts, 80 mm in diameter at the centre of which is a hollow cavity, 36 mm in diameter, which he filled with water.

One of Sutton’s cameras was used in Australia by Richard Daintree (1832-1878) on his geological surveys during which he discovered potential gold and coal fields in Queensland, though the example above is the only one I have been able to find, and only because its negative is displayed in the Museums Victoria images of the camera, from which I have made this positive after enlarging and ‘uncurling’ it digitally.

Earlier in his career and during his visit to the prospering goldfield towns in Victoria including Bendigo, Clunes and Maryborough, and in my home town of Castlemaine, Daintree made mutliple-shot panoramas. One shows Castlemaine’s new market buildings under construction (I digitally joined and straightened them to make the version shown below). The resolution of the image is astonishing and renders detail of individual bricks! This is one of the Victorian series he exhibited to acclaim at the 1862 International Exhibition in London and that year the Melbourne Age newspaper notes that he presented “several interesting transparencies illustrating some of the geographical features of the Geelong district, with a large collection of geological and mineralogical specimens” at a Geelong, Victoria exhibition.

Sutton’s design has been revived recently as the HydroChrome camera.

Human binocular vision encompasses approximately 160º, and Martens’ and Sutton’s aim was to duplicate or exceed that angle of view. The photographic effort followed on from painted panoramas presented in specially built rotundas, such as Daguerre’s Paris diorama which opened July 1822. With the invention of photography painters used it to save time and increase accuracy in the realisation of their painted scenes.

One could also see panoramas at the exhibitions of the Societe francaise de photographie. In 1861, Édouard Baldus showed a Panorama of the Tuilleries and the Louvre, which offered a view of 200º, about which a critic exclaimed that it “is beyond imagination, almost inducing dizziness”

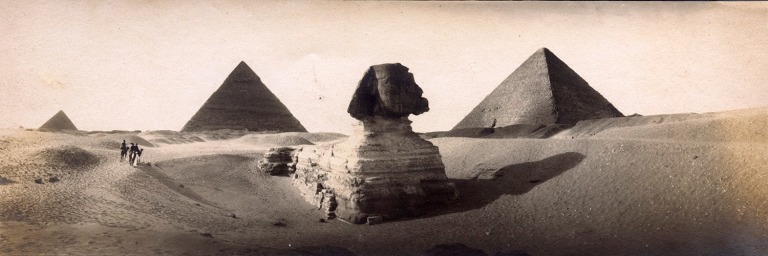

Albert Boime identifies the elevated point of view of the panorama as inviting a “magisterial gaze” that advanced the goal of “Manifest Destiny”. W. J. T. Mitchell calls the genre “the dreamwork of imperialism;” a visual rhetoric of ownership and control embedded in the formal qualities of landscape imagery. Demonstrably, the land-grabbing photographic panorama was a tool of colonialism (and still is, as Rebecca McCauley argues), and such cameras accompanied the Christian tourists (and painters) who flocked to the “Holy Lands” and Egypt.

Joseph-Philibert Girault de Prangey (1842-1844) Jérusalem : vue panoramique. Daguerreotype 8.8 x 23.5 cm. Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Département des Estampes et de la Photographie

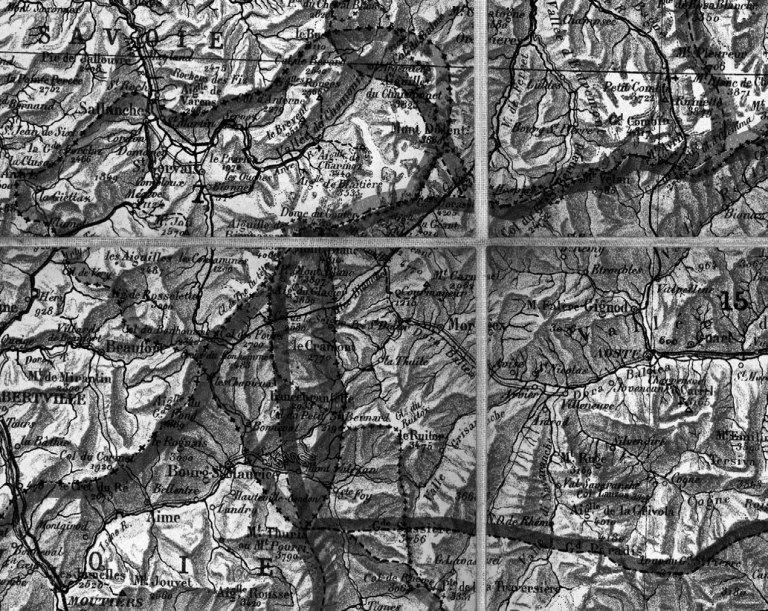

Following the French geologist Léonce Élie de Beaumont work with Armand Dufrénoy during the 1820s and 1830s on the first geological map of France published in 1841, the photographic panorama seemed it would have ostensible and various scientific applications. However, it was not clear, as Jan von Brevern writes, to scientists of the time, especially those attempting to perceive order beneath the apparent chaos of mountain chains, what purpose Aimé Civiale‘s attempt at a complete photographic coverage of the High Alps might serve. His was the earliest systematic photographic study in the earth sciences.

Between 1859 and 1868, by which he had tramped across almost the whole Alpine range with 250 kilograms of photographic equipment, Civale had produced more than 40 large panoramas, including an 1866 circular panorama from the summit of Bella Tola and an 80cm x 4m long panorama of the Berner Oberland, and more than 600 photographs of details.

To “provide physical geography and geology with the indications they await,” Civiale wrote, “the photographs have to be oriented such as to reproduce in the best possible way the structure of the rocks, the disposition of the layers of the terrain, the forms and inclination of the glaciers”…and “to connect the prints it is indispensable,” he explained, “to place the camera in a horizontal position; the instrument turns around its own axis in such a way that the first sheet covers the second by around one and a half centimetres, and so on for the following sheets.”

For expediency he quickly gave up using wet collodion on glass which, though it provided sharper images, was difficult to execute in the mountains, even with the assistance of his teams of assistants (who had to shift position to keep themselves and the equipment out of each shot), and instead employed the dry negative process introduced in 1851 by Gustave Le Gray (1820–1882). The sister process of Talbot’s calotype, its major advantage was that it could be sensitised days or even weeks before exposure. Nevertheless, it was slow, and every exposure took between twelve and fifteen minutes, so that four or five hours passed between the first and last exposure for his 360º panorama, and the sun had quite noticeably changed position.

Writing on 26 April 1869 he acknowledged the support of Élie de Beaumont, secretary of the Académie des Sciences and main proponent of a theory that mountains “constitute groups or Systems“:

“This work, commenced in 1859 and finished in 1868, lasted ten years without interruption. I aimed to provide, as much as I was able to, a complete idea of the great Alpine chains from the geographical and geological point of view. I ask the Académie to accept my thanks for the benevolence and encouragement it offered to me during these ten years of work”

His work was appreciated by geologists including Charles Saint-Claire Deville, a follower of Élie de Beaumont, in 1866 commented;

“M. Civiale has understood that this gap can be filled in an irreproachable manner only by photography. Convinced that the geographer, the geologist, the meteorologist must find in this admirable discovery of our century a means above all controversy and independent of all preconceptions or all personal errors for recognizing the real form and relief of mountain massifs, . . . nothing has been neglected by him to arrive at results that are useful for geology.”

A former student of the École Polytechnique, and once officer in the engineer corps of the French army, Aimé Civiale is recognised as a pioneer of scientific photography as applied to the geography of the mountain environment. He insisted there was a distinction between his “photographs taken under neatly defined conditions” from which geology and the physics of the globe might benefit and the “landscapes that are of interest in picturesque and artistic aspects”, referring perhaps to John Ruskin‘s series of daguerreotypes in the Alps and his claim to have made the first photograph of the Matterhorn, and to Friedrich Martens‘ own photographic panorama of the Swiss Alps that Élie de Beaumont himself had presented to the Académie des Sciences in 1854. He was in fact amongst a number who had photographed the mountain chain, including Jean-Gustave Dardel and Camille Bernabé, the Bisson brothers, Claude-Marie Ferrier, Adolphe Braun, Joseph-Eugène Savioz, Joseph Tairraz, and Gustav Jägermayer though unlike Civale none had distinguished between touristic, picturesque or scientific purpose, nor did they claim to have made “photographs taken under neatly defined conditions,” as he had.

Von Brevern in his paper relates Civale’s photographs to the ‘explorative experiment’ conducted when there is no hypothesis or expectation to satisfy; done systematically in the hope of producing useful data — for their potential — what they supply is ‘incidental’, but copious, information that, it was realised by Aimé Laussedat, Ignazio Porro and others, could be applied in geodesy and cartography in a new science of photogrammetry; if the exact distances between the taking cameras is known, plan views of a site can be drawn from photographs alone, and from panoramic imagery made at sites within viewing distance, multiple measurements can be pinpointed.

Now, in the anthropocene, when Alpine glaciers may seen through the evidence of historic photographs, Civale’s rigorously horizontal photographs of carefully chosen summits of comparable height, deliberately made under closely identical atmospheric conditions prove invaluable — especially so if accompanied by his numerous mineralogical samples, measurements, barometrical readings, drawings, and diary entries which would provide even more granular data — if only the latter, non-photographic records, had survived.

Nevertheless Zumbühl, Nussbaumer, Holzhauser, and Wolf in their 2016 Die Grindelwaldgletscher – Kunst und Wissenschaf identify Civale’s large panorama of Grindelwald as of particular documentary importance. What was ‘incidental’ in his photographs now becomes climacteric.