December 28 is the date on which one of my photographer heroes Ed van der Elsken died in 1990 (see his entry in Wikipedia on which I’ve been the primary author).

December 28 is the date on which one of my photographer heroes Ed van der Elsken died in 1990 (see his entry in Wikipedia on which I’ve been the primary author).

It’s my birthday so forgive my indulgence in looking at someone who these days is a little unfashionable in photography, though still loved by many (and many who are young), not unlike another bad boy of art, Australia’s Brett Whiteley.

I first saw this portrait taken in a pitted mirror in a photography magazine and to my delight found it again in Een Liefdesgeschiedenis in Saint-Germain-Des-Prés (Love on the Left Bank), published in 1956, a year after the more wholesome MoMA exhibition catalogue for The Family of Man, alongside which it sat on my father’s bookshelf. To open its pages in the 1960s was to experience the thrill of the taboo.

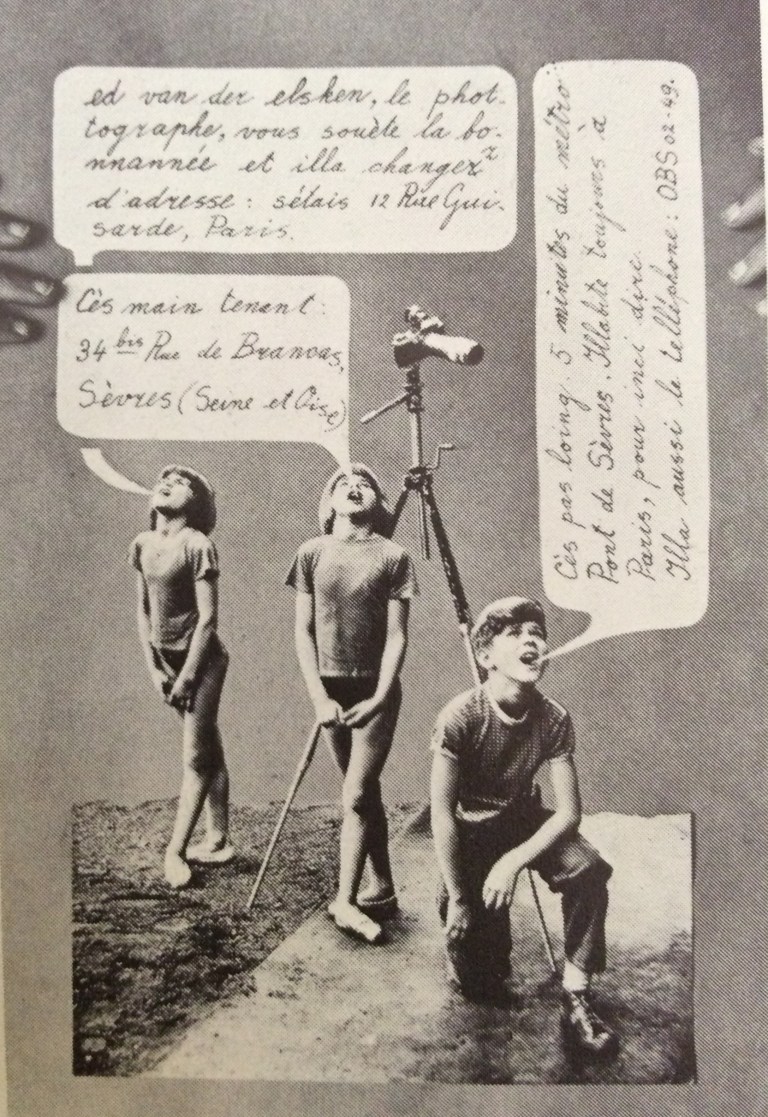

The Dutch call this style of book a beeldroman (‘photo novel’), and Ed van der Elsken’s book is an early example. He had pasted up the dummy of the book by hand, devising a tragic love story from the gritty photographs he had taken in Paris of the disaffected youth of the period after the war, who were even more poverty-stricken than he. He showed it to Edward Steichen who was visiting Europe to collect photographs for his The Family of Man. Steichen encouraged him to get it published. Designer Jurriaan Schrofer produced a ground-breaking cinematic layout based on the photographer’s paste-up. English and European editions quickly sold out and it became the quarry of collectors.

The anti-heroine of this quite existentialist story (which, being photographic, sits between fiction and biography) is ‘Ann’, an exotic dancer and bohemian artist. But really, she is the Australian expat Vali Myers (an exotic dancer and bohemian artist) whom I had the extraordinary good luck to meet in the 90s as she got off a tram. My adoration of ‘Love on the Left Bank’ meant that I felt I really knew her, so I automatically exclaimed “Vali…it’s you”, and to my surprise she invited me to follow her into her studio in the Nicholas building in Melbourne. She was by then instantly recognisable, with her vivid red hair and face tattoos, and had lived her life to the utmost, just as van der Elsken, my hero photographer and another extrovert redhead, had done.

What attracted my teenage self to this photograph was its bohemian romance and its suggestion of surrealism. As my years pass it has become a talisman of my love of photography. It provokes nostalgic memories of the existentialist philosophy I devoured as a young man, but also reminds me of what for me was an idyllic childhood period spent in London in the climate of a Europe still in recovery from the Second World War. Van der Elsken had left for the ‘city of lights’ during the summer of 1950, the year I was born, to find work, but also because like many of his generation of Dutch youth, Ed, a committed pacifist, was disillusioned by the events of the war, the country’s complicity in the ‘disappearance’ of Netherlandish jews, and the blandness of his postwar society.

He had a letter of introduction from Kryn Taconis, Magnum photographer and member of the GKf, to Pictorial Service, the Magnum photo laboratory in Paris. There Ed had the rare opportunity to absorb at first hand the work of the greats of post-war photojournalism, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Capa, David Seymour, George Rodgers and Ernst Haas, as he printed their photographs. Ata Kando worked there too. They fell in love and he went to live with her and her three children.

There is an exhibition of the extraordinary Ata Kandó, I Shall Use My Time, at the Nederlands Fotomuseum until 15 Jan. 2017, curated by Koos Breukel, whose portraits (including one of van der Elsken) I have discussed in another post, and Rose Ieneke van Kalsbeek. Kandó is now 103 years old and still admired by Dutch photographers like Breukel, and at the time of their meeting Ed was twelve years her younger, and she most likely his mentor, infecting him with the various aspects sides of her own work; fashion, the documentary, and her fantastical narrative.

Born in Hungary, she lived in Paris from 1938 and worked there as a child portraitist, but was deported back to Hungary during the war, where her heroic actions in protecting fellow Jewish citizens were fired by her compassion and sheltered by her marriage to a non-jewish artist. Back in Paris in 1947 she met Robert Capa who replaced her lost camera and gave her the job in the Magnum lab, while her husband, Gyula Kandó went back to Hungary for work, but was trapped there behind the Iron Curtain. They divorced and she raised her children on her own until meeting and living with van der Elsken, marrying him and moving to Amsterdam in 1954, but divorcing him a year later.

Kandó went on in 1956 to make a non-profit book on Hungarian refugees which raised $250,000 in funds for displaced Hungarian children, and in the following year traveled with her children in the Swiss alps to make Droom in het woud (Dream in the forest), about adolescence in the form of a fantasy, followed later by her career in fashion photography, documentary work on the indigenous in the Amazon and Kalypso & Nausikaä – Foto’s naar Homerus Odyssee, an elysian sequel to Droom in het woud.

Apart from the Dutch émigrés, among them the painter Karel Appel and the writer Simon Vinkenoog, van der Elsken initially knew practically no one apart from people he met through Ata Kando. Their assignments were intermittent and were processed and printed in a makeshift darkroom in the kitchen of their cramped apartment.

The photos he took while he wandered the streets and that he sold to newspapers were of lovers, tramps and urchins, buskers who rolled on broken glass or swallowed swords for a few sous, street vendors, blind beggars, student demonstrators and rioters, French celebrities including Edith Piaf, Maurice Chevalier or Charles Trenet arriving at events, of showgirls at the Lido, and of the bizarre Nuit de Montparnasse which included a nude beauty parade in front of hundreds of leering press (and amateur) cameramen in a competition to select the best artists’ life model of the year. He was a passionate recorder of the jazz scene at time when top artists included Paris in their tours. Amongst his directly commissioned assignments were a few fashion shoots and a portrait session with Orson Wells.

The photos he took while he wandered the streets and that he sold to newspapers were of lovers, tramps and urchins, buskers who rolled on broken glass or swallowed swords for a few sous, street vendors, blind beggars, student demonstrators and rioters, French celebrities including Edith Piaf, Maurice Chevalier or Charles Trenet arriving at events, of showgirls at the Lido, and of the bizarre Nuit de Montparnasse which included a nude beauty parade in front of hundreds of leering press (and amateur) cameramen in a competition to select the best artists’ life model of the year. He was a passionate recorder of the jazz scene at time when top artists included Paris in their tours. Amongst his directly commissioned assignments were a few fashion shoots and a portrait session with Orson Wells.

His wanderings in the street resulted in some ‘scoops’. This 1951 full-page spread in RADAR, Le Parisien‘s pictorial, provides an example of his reportage; a crise de folie, a crisis of madness, in which a naked man throws his possessions from the seventh floor into Boulevard Saint Germain in front of a crowd of 3,000 before he being plucked from his balcony by firemen on a ladder and arrested.

In a cafe he met a Russian who introduced him to the bohemia of Saint-Germain-des-Prés; young people of every nationality, all cursed by the war, drifters who spent their days in bars, cafes and little restaurants where they eked out a meal or a cup of coffee, dazed by hunger, alcohol and drugs, desperate and bitter. As Vali Myers, who also knew Albert Tucker in 50s Paris, said to Australian critic Christopher Heathcote; “Times were different, it was very much to do with the war. The kids’ nerves were in rags, and unfortunately many of the guys were pretty violent, so there were a lot of street scenes and the cops would turn up. [sighs] Those kids were the refuse, the debris from the war.” The Parisians were tough towards foreigners. There were no handouts. Mixing with them easily, given his age and his own war experience, Ed found some kindred spirits whom he could photograph candidly or pose for photographs.

He made full use of the moody minimal available light, the smoke haze, flare and blur. The photographs show them greedily mopping up a shared bowl of soup with the free rolls, making love in their bedsits or getting drunk and arguing, or dancing frenetically to jazz recordings.

Amongst all this was a great deal of intellectual activity; his camera takes in members of the Lettrist International and Situationists at the cafe Chez Moineau, 22 Rue de Four, around the corner from Ed and Ata’s flat, whose owner was a rough diamond who sympathised with the young down-and-outs, giving them cheap soup on endless credit and who cleaned up their vomit.

Amongst the denizens of these little dives he met Vali Myers, followed her, and most likely had an affair with her. It is she who is the main protagonist of ‘Love on the Left Bank’, who patterns it as if it were under the influence of a magnet, via the editing of van der Elsken and Schrofer, from an unconnected series of brilliant snapshots into a classic of the visual narrative, the photo-roman. Then an opium addict living in l’Hotel d’Alsace Lorraine, 14 rue de Canettes near Place Saint Sulpice not fifty metres from Ed and Ata’s flat, Vali, kohl-eyed and almost terminally skinny, was the perfect anti-heroine. At the time she was making sombre, intricate ink and wash drawings that eventually were to bring her fame and fortune in New York and throughout Europe.

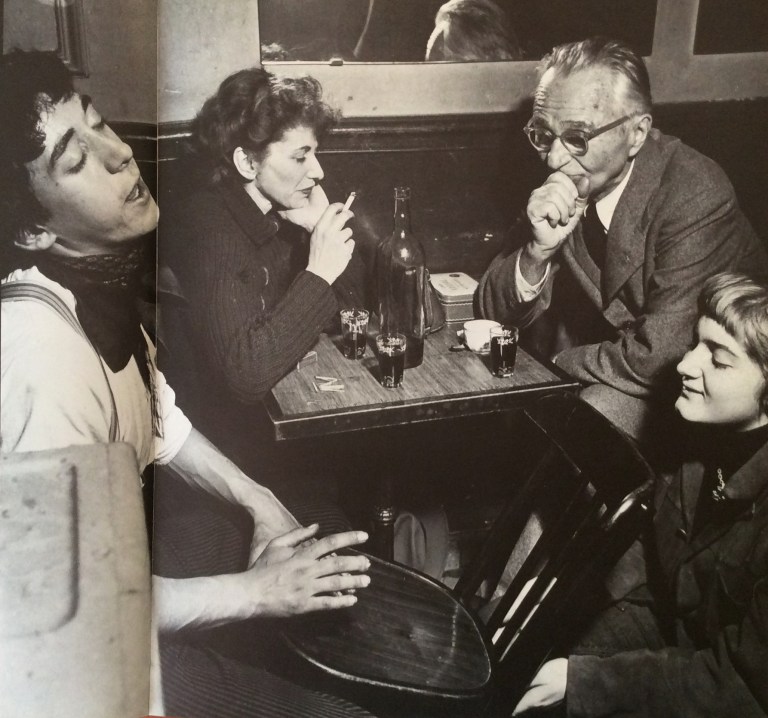

Crammed into a table with Ata Kando at one of these cafes Ed portrays a rather uncomfortable-looking Edward Steichen, the man responsible for the photographer’s rapid rise to international fame, who included eighteen of the photographer’s Saint-Germain-des-Prés images in a survey show Postwar European Photography (1953) and another in The Family of Man, (1955). Here he sits listening patiently to a young man playing bongo on a chair…who, little does Steichen know…happens to be Claude Philippe, the banjo player with Claude Luter’s orchestra around this time (also photographed by Émile Savitry).

Ed devoted his life to photography after seeing Picture Post while posted with some British soldiers in the Battle of Arnheim and also Weegee’s book Naked City (1945). He had some artistic training; a year at an art academy in Amsterdam before the war and a correspondence course that he did not pass. His real education came when he joined the GfK in 1949 after photographing for only two years, making friends with the great Emmy Andriesse, and working in the Magnum darkroom. But the most powerful influence on his career I believe has been his marriages to three photographers; Ata Kando (b.1913), who was remarkable in her own right; Gerda van der Veen (1935–2006) who largely sacrificed her own career to his and in having two of his children Tineloe and Daan, and who really only launched her own photographic career after they had separated; and Anneke Hilhorst (b.1949) who bore him another son, John, and nursed Ed through his terminal prostate cancer. All assisted him on, or co-produced, his projects and each was, to an unknowable extent, his muse.

By all accounts van der Elsken was a difficult red-headed firebrand. He demanded a great deal of himself, down to filming his own death, but he was also tough on those close to him, and on his subjects. During the eighties Ed photographed the Philips physics laboratory in Eindhoven, from which Boerhaave Museum assembled the exhibition Hit & Run; more than a hundred original prints, never before shown outside Philips, ‘a world peopled with quirky researchers in new technology’. ‘Hit and run’ is an appropriate term for Ed’s approach. Ever eager to get the shot, he increasingly adopted the ‘in-your-face’ attitude of the likes of street photographers William Klein and Garry Winogrand; shoot first and only answer questions if they catch you.

There are ethical issues in his photography, but the upshot is that most of what he did is now an irreplacable record, as close to real life as photography can get; along with Klein (but not Winogrand), he was an early exponent of ‘subjective photography’ and ‘first-person filmmaking’ in which the photographer, though unseen, is understood as present (and even heard…he conducted his interviews from behind the camera whilst filming single-handed). The shot below represents an early experiment with this approach…

Sheer ambition and drive ensured his success in making 22 books and nearly 50 movies, but his somewhat acerbic manner did not endear him to colleagues and made sticking to editors’ assignments a trial. No doubt his manner made him difficult to live with too, as three marriages might attest. But then, who am I to talk?

I could go on, but suffice it to say he’ll remain my hero, flawed as he was, but the women in his life; they deserve more attention in other posts. In the meantime, another woman of photography, Nan Goldin, writes, much more eloquently than I, about Ed in The New Yorker in a text drawn from the exhibition catalogue for Ed van der Elsken’s “Camera In Love,” which is on view at the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam through May 21st. The catalogue will be published in March by Prestel Publishing.

13 thoughts on “December 28: Ed”