July 4: Ceramics and photography seem unlikely partners, and yet they have been together since the birth of the younger medium.

July 4: Ceramics and photography seem unlikely partners, and yet they have been together since the birth of the younger medium.

One finds them in combination in myth, as recorded by Pliny the Elder’s voluminous The Natural History which incorporates in Book XXXV ‘An Account of Paintings and Colours’ and in its 43rd chapter names ‘The Inventors of the Art of Modelling’:

…Butades, a potter of Sicyon, was the first who invented, at Corinth, the art of modelling portraits in the earth which he used in his trade. It was through his daughter that he made the discovery; who, being deeply in love with a young man about to depart on a long journey, traced the profile of his face, as thrown upon the wall by the light of the lamp. Upon seeing this, her father filled in the outline, by compressing clay upon the surface, and so made a face in relief, which he then hardened by fire along with other articles of pottery. This model, it is said, was preserved in the Nymphæum at Corinth…

Butades first invented the method of colouring plastic compositions, by adding red earth to the material, or else modelling them in red chalk: he, too, was the first to make masks on the outer edges of gutter-tiles upon the roofs of buildings; in low relief, and known as prostypa at first, but afterwards in high relief, or ectypa. It was in these designs, too, that the ornaments on the pediments of temples originated; and from this invention modellers first had their name of plastæ.

Isn’t this also a record also of the first form of photography; the tracing of shadows, and their transformation into three-dimensions with sculptural ceramics?

Our impulse to photograph is often from a desire to preserve what we love and what may be lost. That is also evoked in this tale of lovers soon to be separated by war.

The painter of Pliny’s story of the Corinthian Maid, above, is Joseph Wright, whose paintings evince a fascination with the effects of light (think also of his vivid An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump), and he was a friend the famed industrial potter Josiah, who was father of Thomas Wedgwood.

Ceramics and photography thus are united again in young Wedgwood’s conception of photography that appeared in the first issue of the Journals of the Royal Institution of Great Britain of June 1802 in his An Account of a Method of Copying Paintings upon Glass, and of Making Profiles, by the Agency of Light upon Nitrate of Silver. Invented by T. Wedgwood, Esq. With Observations by H. Davy. [Humphry Davy (1778-1829)];

White paper, or white leather, moistened with solution of nitrate of silver, undergoes no change when kept in a dark place; but, on being exposed to the day light, it speedily changes colour, and…becomes at length nearly black …

The condensation of these facts enables us readily to understand the method by which the outlines and shades of painting on glass may be copied, or profiles of figures procured, by the agency of light ….

When the shadow of any figure is thrown upon the prepared surface, the part concealed by it remains white, and the other parts speedily become dark ….

The images formed by means of a camera obscura, have been found to be too faint to produce, in any moderate time, an effect upon the nitrate of silver. To copy these images, was the first object of Mr Wedgwood, in his researches on the subject, and for this purpose he first used the nitrate of silver, which was mentioned to him by a friend, as a substance very sensible to the influence of light; but all his numerous experiments as to their primary end proved unsuccessful … Nothing but a method of preventing the unshaded part of the delineation from being coloured by exposure to the day is wanting, to render the process as useful as it is elegant.

‘The Agency of Light upon Nitrate of Silver‘ had been noticed already in 1717 by Johann Heinrich Schulze (1687-1744) who had discovered that a chalk, nitric acid and silver solution was responding to light, not heat, when it darkened under stencils he applied to outside of the bottle, and he experimented with light from a prism to determine that it reacted most strongly to the blue end of the spectrum. Elizabeth Fulhame experimented also with silver nitrate and published in her An Essay on the Art of making Cloths of Gold, Silver, and other Metals, by chymical processes (1793), as did Henry Brougham in his unpublished experiments (c.1795).

As Geoffrey Batchen notes in his “Tom Wedgewood and Humphry Davy,” in History of Photography, 17, 2 (1993), pages 172-83, it follows that Wedgwood was guided toward his discovery and ideas for its practical application by being surrounded by the industry of ceramic production in which a rapid and automated means of transferring two-dimensional designs to three-dimensional ceramic bodies (Method[s] of Copying Paintings upon Glass) would be so valuable.

A contemporary reference to the conjunction of clay and camera is found in the work of Tim Maslen, born on this day in 1968 in Perth, Australia, who works with Jennifer Mehra (*1970, London) in the collaborative team of Maslen & Mehra.

A contemporary reference to the conjunction of clay and camera is found in the work of Tim Maslen, born on this day in 1968 in Perth, Australia, who works with Jennifer Mehra (*1970, London) in the collaborative team of Maslen & Mehra.

Their next exhibition will be in the UK at Hastings Museum & Art Gallery, Bohemia Road, Hastings, East Sussex from 1st September – 12th November, where their work Cash, Clash and Climate is a collaboration with local street artists Shuby and Delete; sculptural forms, the majority of which take the form of images on plates (normally ceramic, but in their case a more expedient papier-mâché) incorporating drawings from photographs to pose questions about political, social and economic structures and how they, in turn, relate to social unrest and environmental issues.

I believe that their exhibition will incorporate some of their photographs. Their series Impermanent Collection, three years in the making and already widely shown, is an approach that ingeniously combines the sculptural and the photographic in a manner that illuminates the discoveries of Wedgwood and Davy.

For this series, which they call ‘temporary interventions with mirrored sculpture and drawing’, were shot with a Mamiya 6 x 7 film camera in locations in which they had placed aluminium mirrors. Each is hand-cut or laser-cut to the silhouette of an item from a major collection, in most cases found on their multiple visits to the Victoria & Albert and British Museums, London; the Metropolitan Museum, New York; the Archaeological Museum, the Turkish and Islamic Art Museum, Istanbul; and the Asian Museum of Civilization in Singapore. The internal details are drawn on the surface in black, from photographs of the objects.

The strategy enables the colouring of the mirrored object by reflection of its surroundings, and also convinces us, through the 2D window of the photographic print, that we are seeing a three-dimensional sculptural form delicately set on a plinth formed of stripped tree bark embedded in a bed of moss. What appears solid is actually insubstantial, the trace of an image, not unlike the silhouettes of stencils that Wedgwood found were fleeting and impermanent.

Stucco with pigment, V&A Museum

In this case the subject is copied from the V&A’s exquisite, princely head of the Buddha in plaster stucco shaped from a mould with hair, including the prominent hair-knot (ushnisha), and other features modelled by hand in a Graeco-Roman style. Found in Afghanistan and once part of a large-scale narrative panel modelled in high relief, this head was richly polychromed, and traces of red remain on the lips, eyelids and hair.

Maslen & Mehra colour it in an ethereal blue rendered from painterly reflections that are thrown into hazy soft focus by the shallow depth of field of the 6×7 cm format SLR film camera. In some cases they have used fabrics of the desired colour for the reflections in these works. Against the rich emeralds and green of the background, the blue forms a spiritual aura.

In some cases, as in the image of the 16th century Iranian helmet above, the object almost vanishes into the background and the drawn marks are left hanging in an indeterminate void.

Elsewhere, a figure may find itself amongst sympathetic forms of the landscape; here a drawing on aluminium of a Hellenistic sculpture is placed within the crumbling moss-covered skeleton of a tree-stump. It appears to be of the same scale as the sculptural antiquity which in the original is over life-size. The reflections actually serve in this case to round out the form, to darken the face within its veil and to tint its drapery in subtle verdigris.

To be included in a permanent collection is the dream of most artists; to be preserved amongst the canon of art in a museum, an exemplar of your style. In referring to this body of work as Impermanent Collection Maslen & Mehra intend some irony but also draw attention to the ultimately fugitive nature of archaeological antiquities and the contingent nature of any ‘canon’. They underline this by including fashion, the ultimate art ephemera, in their ‘Collection’ in the form of shoes, both contemporary and historical, such as one of designer Christian Louboutin’s (*1964, France) high-heels which he brought back into fashionable popularity in the 1990s.

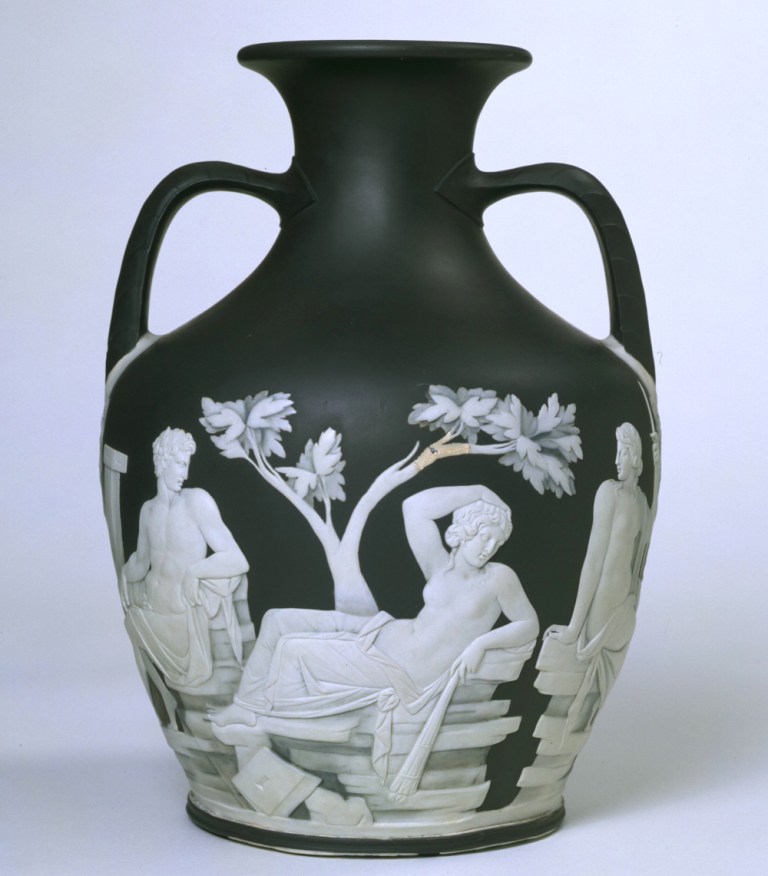

Wedgwood ware typically combined neo-classical designs and Graeco-Roman ceramic forms and it was the copying of these forms using a copying machine invented by James Watt, also a friend of Tom Wedgwood, and with light-sensitive materials, that these devices were intended to assist and automate industrially.

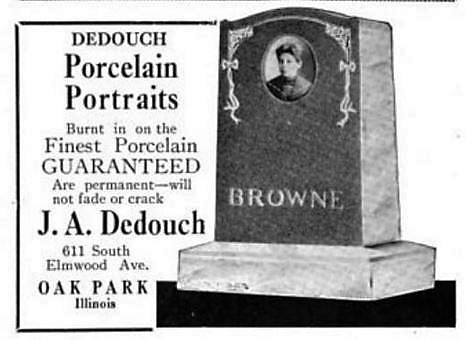

A true fusion of photography and ceramics as envisaged by Wedgwood was long in coming, achieved twenty years after the invention of the new medium when in 1854, Frenchman Leron de Marcarson patented a process of vitrifying photography onto porcelain using the gum bichromate process.

In 1855 Lafon de Camarsac produced the first instructions for ceramic photographic prints in a memoir Application de l’heliographie aux arts ceramiques presented to the French Academy of Science, published in Paris by C. Chevalier. He used the wet collodion process to create silver-based images and then he replaced the silver with gold or platinum which could survive the porcelain firing process. Three years later in 1858 Henri Garnier and Alphonse Salmon, also in France but this time in Chartres, carried out diverse experiments that led to stable photoceramics.

After 1860 when gelatin was being used in photography a layer of light-sensitive gelatin emulsion containing colored enamel glaze was coated onto ceramic pieces, exposed with a negative, washed in water to develop the image and fired.

The 1887 Universal Exposition displayed numerous examples of porcelain vases decorated with such fired photographs. The primary use of this process was to put images on gravestones which still appear in cemeteries as evidenced by the portrait plaques in Polixeni Papapetrou‘s 1990 photograph from a poignant but humorous series she made of fans at the Elvis Memorial in Melbourne.

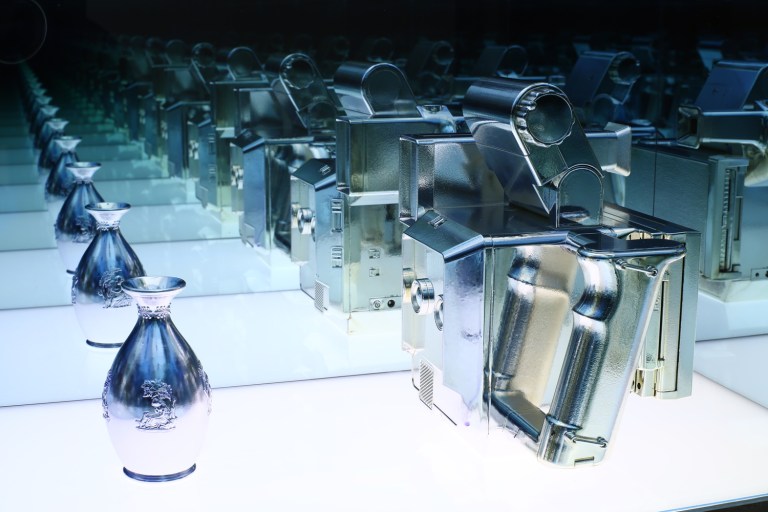

This concept of copying and automating is represented by Canadian artist Andrew Wright (*1971, UK).

His Disused Portrait Camera Considers Wedgwood Vase (2015) copies itself; placed inside a vitrine with a front panel of 2-way mirror it is reproduced ad infinitum. It consists of a Polaroid camera and a vase that have both been silvered. Thomas Wedgwood patented an invention of ‘silvered ware’ in about February 1791 which produced a pattern of silver upon a black earthenware body, so Wright’s work makes multiple references to the Industrial Revolution that drove Wedgwood’s ingenuity.

The relation of pottery to photography is not as improbable as it might seem.

4 thoughts on “July 4: Glaze”