July 16: Early photography and printmaking walk hand-in-hand into the forest.

July 16: Early photography and printmaking walk hand-in-hand into the forest.

Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot was born on this date in 1796. We know him as an early Realist painter of the French Barbizon school, but in one sense he was also a photographer; he made his glass plate negatives by hand, but contact-printed them in the usual manner, in a technique now known as cliché-verre.

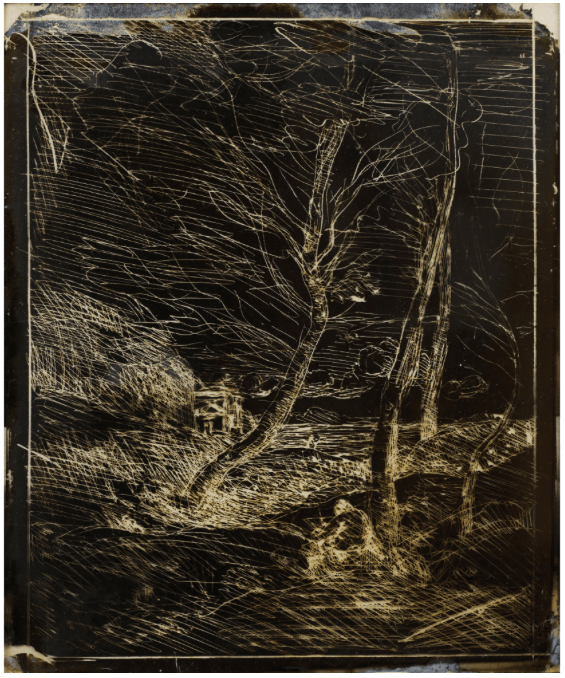

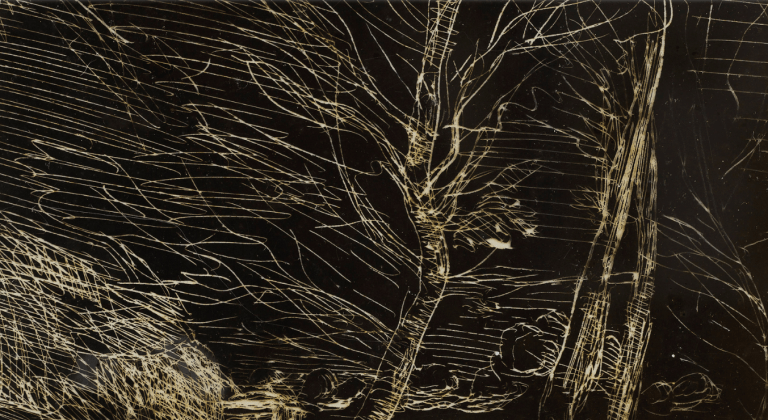

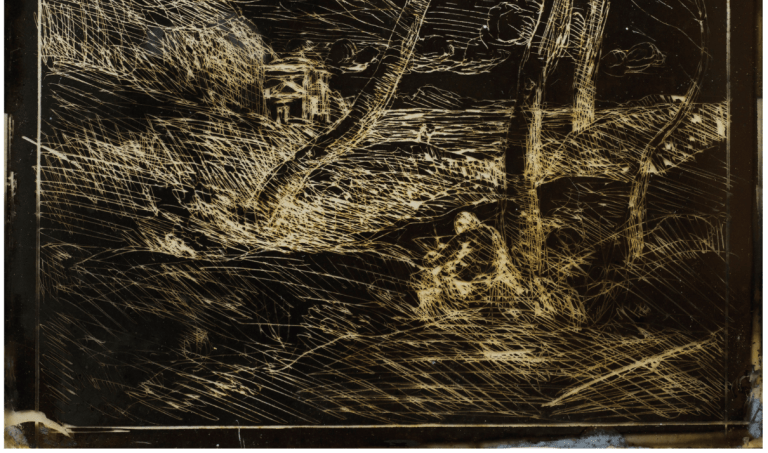

Various explanations of the method he used to make his plates appear in the literature, but all agree that Corot’s experience with the technique and exposure to photography in general were formative. In one account he used collodion-coated glass plates blackened by exposure to light to create a light-blocking ground into which he would etch lines and hatchings. These ‘negatives’ were then contact-printed onto salt or albumen papers to make photographic reproductions of the prepared drawings.

The cliché-verre process was introduced to the public in 1839 by three experienced British printmakers James Tibbits Willmore (1800–1863), William Havell (1782–1857) and his brother James Frederick Havell (1800–1841). In March 1839, two months after William Henry Fox Talbot (1800–1877) announced his cameraless “photogenic drawing” process to the Royal Society, they exhibited cliché-verre prints at the same institution. Significantly, the technique, a hybrid of the two media, was included as early as 1841 in both photographic and printmaking technical manuals; Robert Hunt‘s A Popular Treatise on the Art of Photography, and T.H. Fielding’s The Art of Engraving.

The medium was independently discovered in France by the amateur photographer Adalbert Cuvelier (1812-1871). With Léandre Grandguillaume (1807–1885), a professor of drawing in Arras in northeast France, he introduced the cliché-verre to Camille Corot, whom Cuvelier met in 1852, during one of the painter’s frequent visits to Arras, and to his circle of artists —the ‘School of Arras—in the 1850s and 1860s that included the landscape painter and lithographer Constant Dutilleux (1807–1865) who in 1847 purchased a painting from Corot which had been rejected by the Salon, and from this time their friendship continued until Dutilleux’s death in 1865. Corot took to the method immediately, making clichés-verre for Adalbert to print (fifteen of Corot’s plates remained in the Cuvelier family until 1911). Joining the group were lithographer and photographer Charles Desavary (1837–1885) and photographer Eugéne Cuvelier, son of Adalbert (1837–1900).

- Adalbert Cuvelier (1853) Along The Scarpe River, near Arras, salt print, initialed and dated by the photographer in the negative, mounted, matted, 19.7 by 25.7 cm.

Adalbert Cuvelier was insistent on the artistic value of photography, and there is a pictorialist quality to his work;

Many people who never concerned themselves with drawing or painting…figured that the discovery of [photography] would immediately permit anyone who could buy a camera and all of the equipment along with instructions for using it, to create marvels. They were wrong. I wouldn’t say you have to be a painter or draftsman to make good photographs, but you have to be an artist, that is to say you have to have the sentiment of painting…Photography, properly understood, is not a trade, but an art, and, consequently [the photographer’s] aesthetic sensibility and knowledge must be embodied in his works just as those of a painter are expressed in his paintings.

Willmore and the Havell brothers used etching ground (asphaltum) applied to glass plates and blackened with lamp soot, but the wet-plate process soon provided a more convenient solution. Collodion, or nitrocellulose, could be used to make explosives known as gun cotton and was a flexible, paint-on dressing for wounds (1846, and still in use), and also led to the creation of the first plastics. Its properties enabled a more adherent coating of glass with photo-sensitive emulsion for Frederick Scott Archer‘s ‘wet-plate’ process of 1851, largely superseded by the more practical dry-plate by the mid-1860s when this image was made.

Inspection of an example made by Corot illustrates the practical challenge presented by the technique, one which has always puzzled me. Being a negative, the lines made in drawing the image appear against black and in cutting and incising them, the plate must have been held against a white surface to make them visible.

Drawing white lines that will be ultimately rendered black in the photographic print requires a sophisticated understanding of the relative tones that would appear in a positive print. In addition, collodion is not an entirely cooperative medium in which to make marks; being brittle it tends to crumble, chip and fall away as has happened in this example between the tree trunks.

However, the advantage of this method of drawing to produce a print is obviously speed. A wood or metal engraving requires the application of pressure to painstakingly guide the burin. Clichés-verre are similar to etchings in terms of their preparation with a dark ground which for etching is asphaltum or other acid resist, applied before the design is scratched into it, but the acid etching itself is a further step not required with the cliché-verre.

Furthermore, in making a print a decision could be made to produce a softer image by flipping the plate so that the emulsion was on top and the light transmitted through the incised lines would blur slightly, and for a more pronounced fogging effect, a clear sheet of glass could be added underneath so that the drawing was at a further distance from the paper emulsion receiving the image.

Lithography, invented only in 1896, was being adopted by artists such as Delacroix, Goya and Gericault by the 1820s, but despite the facility and lightness of touch with which they could draw on the stone, printing required further, quite technical steps whereas the cliché-verre need only be exposed and developed.

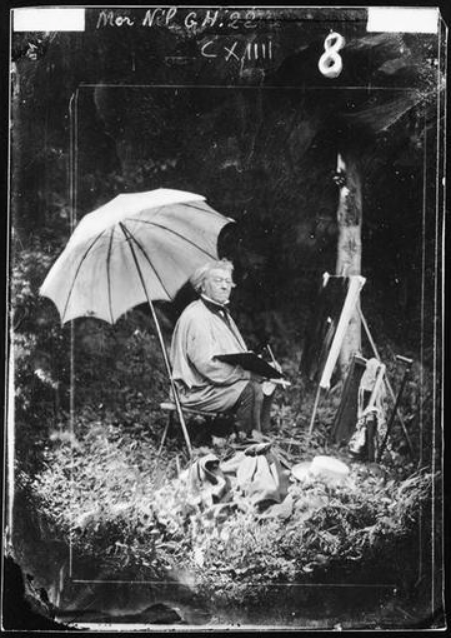

Corot here is clearly able to make marks in the collodion emulsion as quickly as he would make a sketch on paper; the act we see his subject performing in this landscape…

Corot became interested in photography, taking photos himself through his acquaintance with early photographers including Desavary and Cuvelier, and acquired theirs among the 200 photographic prints in his own studio from which he drew inspiration.

As a reaction he partitioned his painting palette in accord with the monochrome tones of photographs. He writes of the division of tones (not unlike Ansel Adam’s Zone System), that he renders in his cliché-verres with crosshatching, and in the printing of his plates;

In preparing a study or a picture, it seems to me very important to begin by an indication of the darkest values… and to continue in order to the lightest value. From the darkest to the lightest I would establish twenty shades.

In comparing these drawings with photography, the etymology rewards some attention; verre of course means glass, and un cliché is French for a photographic negative, but it also signifies any photograph, especially as the equivalent of the English expression ‘a shot’ or ‘snap’. However in the visual arts it is also the technological term for an engraving block or plate, or even a block of type.

It also has come to mean in French, as it does as adopted by the English language, any phrase or expression that has been repeated so often that it has become commonplace or predictable. In this context that idea refers to repeatability, a valuable attribute of the medium.

Barbizon on the outskirts of the Forest of Fontainbleau had already attracted regular visits from landscape painters who were regular guests at the village inn (as were Georges Sand, the Goncourts and other romantics). Adalbert Cuvelier visited annually bringing his photography students from Arras. In 1859 his son Eugène married the inn-keeper’s daughter and settled in Barbizon and there showed the cliché-verre process to Jean-François Millet, Théodore Rousseau and Charles-François Daubigny and printed their glass plates, which remained in his possession.

At Arras and at Fontainblau Corot eventually produced 65 such plates, two-thirds of his graphic output, which were catalogued by Loys Delteil (1869–1927) and published in 1910, however other Corot cliches-verre have been discovered since.

The results are not trite, but simply as beautiful as his descriptions of making art in the open air in front of the subtly changing scene—an inspiration to any landscape photographer;

The whole landscape lies behind the transparent gauze of the fog that now rises, drawn upwards by the sun, and as it rises, reveals the silver-spangled river, the fields, the cottages, the further scene. At last one can discern all that one could only guess at before.. .The sun is up! There is a peasant at the end of the field, with his wagon drawn by a yoke of oxen.. .Everything is bursting into life, sparkling in the full light – light, which as yet is still soft and golden. The background, simple in line and harmonious in colour, melts into the infinite expanse of sky, through the bluish, misty atmosphere. The flowers raise their heads the birds flutter hither and thither.. .The little rounded willows on the bank of the stream look like birds spreading their tails. It’s adorable!

The fields lose their colour, the trees form but gray or brown masses… the dark waters reflect the bland tones of the sky. We are losing sight of things – but one still feels that everything is there…

In Corot’s imagery of the forest, we see photography and printmaking traveling together a short distance, before once again, a hundred years later in the era of Pop Art, they join hands once more.

4 thoughts on “July 16: Cliché-verre”