November 1: Digital technologies are integral to the most experimental and innovative printmaking.

November 1: Digital technologies are integral to the most experimental and innovative printmaking.

Castlemaine Art Museum is currently staging the third of its Experimental Print Prizes donated by local architect Michael Rigg.

Significantly, at least half of the artists use digital means in creating their images or in printing them, or both, while others use photographic means with photogravure or cyanotypes. The transfers used for her ceramic work by Lala Zarei are from digital files ; Di Christensen mentions working from photographs in her drypoint Re-Earthing 1: Burrowing on Fabriano paper curled to represent a weathered tree trunk; Kay Dixon in her Under the Milky Way uses the saturated blue of the cyanotype.

Intrigued in particular by the work of Aylsa McHugh, I contacted her for an interview:

James McArdle: I’ve just been to the the artists’ talks for the Experimental Print Prize. I just wanted to let you know that I admired your work and am particularly interested in its photographic and architectural elements; you trained in sculpture and here you are now printmaking and working with photographs. Can you tell me how all that came together?

Aylsa McHugh: In 2002 I studied sculpture Bachelor of Fine Art (Sculpture) at the Victorian College of the Arts, and it’s only just been since 2017 [when McHugh studied at Northern College of the Arts and Technology] that I’ve been working with found photography. I had a family…a son and I worked from a home studio, so sculpture wasn’t very practical. And I’ve also got, I’ll admit, a bit of a, um, a book hoarding problem; it’s out of control. It’s lucky we’re not on Zoom; you’d see me surrounded by books and ephemera. I got interested in collage in about 2017, and that has been almost exclusively my practice for the last 6 years.

James: And you’ve had a bit of a breakthrough recently and people are paying attention to the work. The Print Prize is quite competitive; they selected only 28% of the of the entrants.

Aylsa: It was really a surprise James because I’ve entered it before. With these things I think, “oh I won’t bother,” and then I’m like, “well why not? You’ve got to be in it.”

Printmaking was where everything took off for me. During the COVID lockdowns I applied for the Creative Victoria emergency grants and was successful. My proposal was to go and work at Baldessin Studio to do the photogravure workshop with Silvi Glattauer [whose exquisite Tidal Flats 3 in that medium is in the show]. Up there I produced a series of photogravure prints that no one really saw because the exhibition was in between lockdowns.

One of those prints I entered into the 2021 Geelong Acquisitive Print Prize, and on the back of that, one of the judges, who was a curator at the National Gallery of Victoria, saw the work; that’s how I got my Sinnsear [meaning ‘elder’ or ‘ancestor’ in Irish Gaelic] into the. print portfolio of Melbourne Now.

James: Wasn’t that brilliant! It’s a recognition of the quality of the work and the fact that you’d been and persistently refining it. So this latest work is a development on previous work playing off the idea of the architectural nature of hairstyles, which is a lot of fun. People would respond to those because it’s just so funny in many ways, but at the same time, you are connecting to the history of modernist sculpture and abstraction. That’s applied in reference to 1950s, 1960s, beehive hairstyles and that in itself connects to space-age modernism. While it is a lot of fun that, historically, has perhaps not been particularly well explored.

And you don’t have a hairdressing background?

Aylsa: You’re going to laugh; my partner’s father is a barber and he’s gorgeous, an old-school Sicilian barber, and he’s very, you know, he reads a lot. He’s an incredibly intelligent man, but just through circumstance, being an immigrant, he ended up working in a barber shop. When I first met my partner and I was studying sculpture at the time, I had this incredible conversation with him, one that we would revisit, where he would talk with such love about sculpting hair. It was his artistic expression and he really loved it when someone came in and wanted, you know, a sculptural cut.

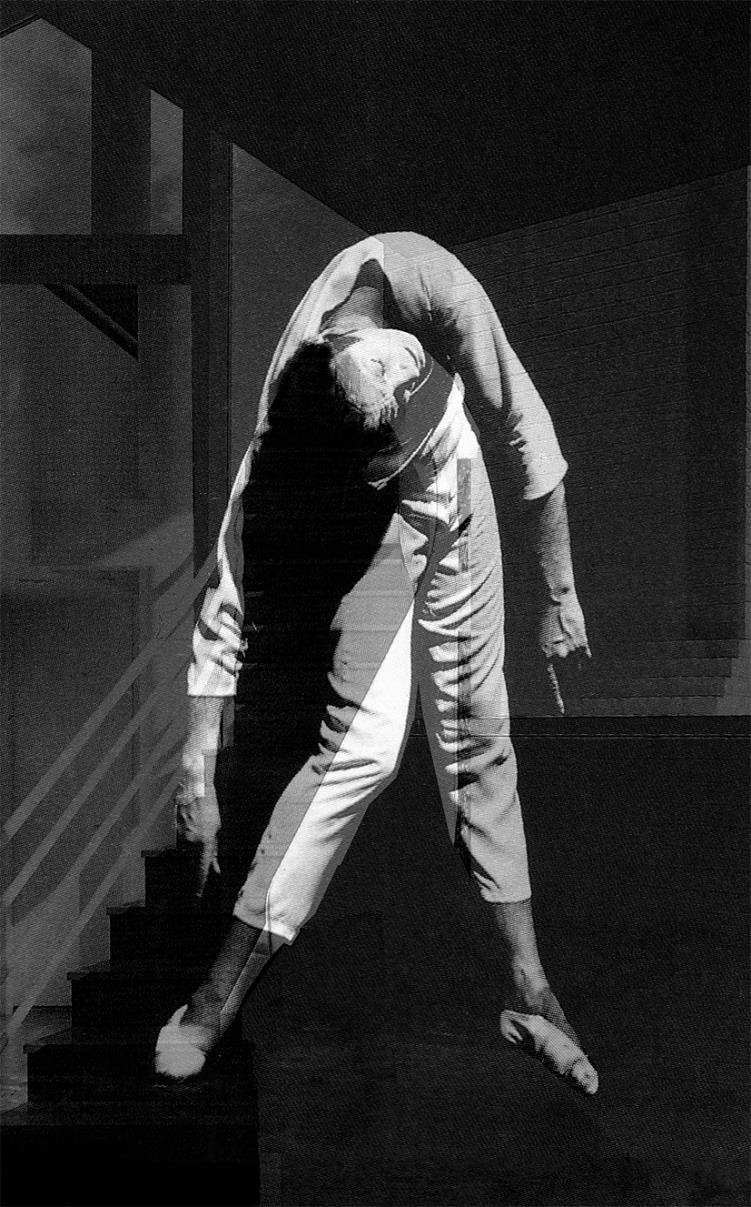

James: So this latest work starts to shift into a much more architectural dimension, including your Dahman-allaidh in the Experimental Print Prize. I love the tensions in it; the little tiny bit of landscape that appears in the top right hand corner, the stress in the figure’s acrobatics (I note the title means ‘spider’ in Gaelic) and then the way that the geometry of the work stretches those tensions even further. So tell us a bit about the format; you’ve been working with photogravure, which is a pretty tough medium, unforgiving and, and so let me start with Baldessin Press and what you learned about photogravure and why you enjoyed that and how the metal plate in this case plays off.

Aylsa: Yes, sure…you’ve got it exactly. That’s why I started printing on aluminum. Because when I was working at Baldessin studio, I just absolutely fell in love with the image on the metal plate; probably more so than the ink pressed into the paper. Much to Sylvie’s bemusement I became completely obsessed with these plates. Working at Baldessin Studio was a big turning point in my work; I started really thinking about negative space and composition and black and white image making. Which is what I’ve almost exclusively been doing since then, working in monochrome. If I fall into a big pile of money I may be able to make more photogravure prints at some point.

I’ve got a huge collection of books and noticed, quite organically, that I was attracted to books on the human body, especially in theatre or dance, and also modernist architecture. Combining the two felt like a natural connection. One image I used for the experimental print prize was one such found image. I knew what I wanted to happen. There’s a lot of things going on in that piece in terms of what I’m referencing and what I was inspired by, but specifically I wanted a figure that would back bend down the stairs with the hair cascading down the bottom of the steps.

By serendipity I managed to find online that image of the model with a search… something ridiculous like “back bend The Exorcist”; you know the scene in The Exorcist, where she’s crawling…it just stuck in my mind… a movie I watched probably when under-age back in the eighties or earlier.

Then I found that image of the architectural space and there was a whole series that I did for a solo show Numinous at Mary Cherry gallery earlier this year with 11 works all on a similar theme; two-part collages with a figure and modernist architecture, each with two images that I think will marry well together. It’s a process of experimentation. Originally the figure on the steps was really small. I meticulously cut it out and, you know, it just wasn’t working. And it was just through that process of coming back to the two images, working on something else, coming back again, and then just experimenting until I found something that worked.

James: And you’re working mainly on the screen…?

Aylsa: I am…which I never thought would happen James, because my background is in sculpture and collage. As I started it was all very much analog, you know, looking at paper texture, marrying colours together, that sort of thing. But I just wanted, I wanted the images to be bigger. And a lot of the time the images I’m working with are tiny—six or seven centimetres, really small images—I wanted to make them bigger and have more presence and digitally is the only way that I could achieve that.

Well, I’m quite happy. I’m now moving in to—surprise, surprise—screen printing. So before talking to you today, I was thinking about the previous solo exhibitions I’ve had. Almost every time I have an exhibition, I change the print format; I didn’t realise that until I was thinking about talking to you. And the next exhibition will be again, a development on that theme of, you know, really simple two-part digital images again; an architectural space if I want to. Screen print onto fabric to honour that pixelation

James: So have you got access to screen printing facilities?

Aylsa: Well. Fortunately, look, I work I work a couple of days a week in a similar role to some of the artists that work at Arts Access Victoria [which is the state’s peak body for arts and disability, a disability-led arts organisation] I work with a young man who is an artist who also happens to have Down’s syndrome, and we’re in a shared studio space. One of the guys in that studio space is a screen printer, so I’ve just been chatting with him and we’re just going to run up one screen and see how it goes.

James: And the great thing about screen printing is the scale; you can really pump it up…

Aylsa: Yeah, exactly, I’ve got friends that have worked with Stewart Russell at Spacecraft studio. He’s meant to be the best in the business [and has worked with Sonia Boyce, Aesop, NGV, Glenn Lygon, Vivienne Westwood, Joseph Kosuth, Yinka Shonibare, Denton Corker Marshall, Joe Casely-Hayford, MCA Sydney, John Wardle Architects, Yhonnie Scarce, Arm Architects, Brook Andrew…] but you’ve got to have, you know, a few grand in your back pocket….if I ever get a show at ACCA or something…

James: Well, I think you’re on the way. It was fantastic getting into Melbourne Now; a credential that is very useful.

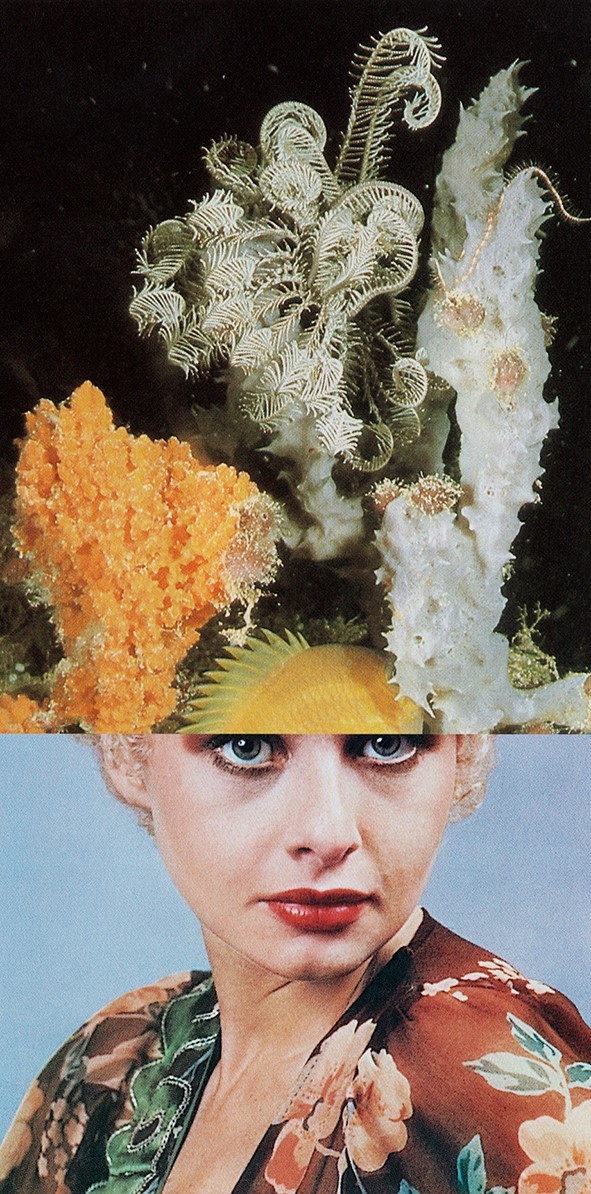

McHugh’s latest solo show, which included Dahman-allaidh, was Numinous at Mary Cherry 25 May – 24 June 2023, and the following images are from that exhibition…

Surveying her works in that show, I remember that I was one of a small band of Australian photography students who, when the The Exorcist appeared in 1973, were being steeped in American photo culture; at the time we antipodeans knew no other; Henri Cartier-Bresson and J.H. Lartigue being mere faint blips on our radar and Australians like Max Dupain nowhere visible. With such imagery drilled into us, we might be prompted to recognise, in McHugh’s raw material for her earlier magazine collages and later digital montages, familiar images. Above, Edward Weston‘s Nude (1936) of his teenage companion Charis Wilson, made in his cramped cottage shared with his sons, and during his initial infatuation with her, is melded in McHugh’s Concretion with what may be a Noguchi sculpture. Their undulating forms uncannily overlap, especially at Charis’s shoulder, despite their quite disparate scale. The architecture into which McHugh places them is incidentally appropriate to this, Weston’s venture into figurative modernism.

In her The Return, the figure entangled Laocoön-like in a nightmare zigzag of louvres and slats is from Barbara Morgan‘s photograph of Martha Graham’s performance of Lamentation, a modern dance choreographed to Zoltán Kodály’s 1910 Piano Piece, Op. 3, No. 2 and representing grief amidst the Great Depression. It was made in the same year that Morgan moved from California to New York City in 1930 and Lamentation premiered at Maxine Elliot’s Theatre in New York City on 8 January that year. She photographed Graham in her studio, giving her more control over the images she produced.

Tremendum presents a less immediately recognisable source; an elastic, slumping figure who appears to be suspended by one shoulder-blade. His legs dangling, he’s in imminent danger of a painful tumble down a steep modernist staircase, or of being bruised against its unyielding metal handrails. These architectural features, as in McHugh’s other work from this series, pass through the silhouette of the body superimposed upon it, and here, at the junction of an angled brick wall with the featureless black triangle of ceiling, the figure is made to hang. Printed on metal, it presents a brute spectacle. The epic scale of these figures as arranged in these montages is echoed in this 1936 image from a special Olympics edition of the German magazine Die Woche.

Note the picture credit ‘Rosemarie Clausen,’ which leads us to the name of photographer of the original in Tremendum. She, like Barbara Morgan, was a photographer of dance and theatre as well as making portraits of German musicians that still feature on Deutsche Gramophon classical music albums. According to Fritz Gruber’s 20th Century Photography (Museum Ludwig Cologne, Taschen 1996) Rosemarie Clausen (née Kögel, 1907–1990) began her career in Berlin in 1925, specialising in theatre photography after initially studying art. She worked with theatre photographer Elli Marcus until 1933, and married German colour film pioneer Jürgen Clausen in 1934. She established her own studio and primarily worked at the Gendarmenmarkt state playhouse, where Gustaf Gründgens was the director in 1934. In 1938, she published her first picture book, “People Without Masks,” showcasing her theatre photography of Germany’s most significant performers.

The cover ominously features a subject of this family portrait, also from 1938. Clausen became friends with actress ‘Emmy’ and through her, was commissioned by Emma’s husband Reichsmarshall Hermann Göring to produce propaganda like that above, of theatre staged during the Olympics to convince international visitors of the cultural capital and benign intentions of the Nazi regime.

During WW2 she photographed Göring at the command post of the Air Fleet 2 (Luftflotte 2) on the English Channel; awarding Iron Crosses to Werner Mölders, Adolf Galland and members of the I/KG 26 bomber command in Wevelgem, Belgium, members of the II/KG 53 bomber command in Tournei, France and members of the I/KG 76 and II/KG 76 bomber commands. Also views of an inspection tour of Air-Sea Rescue Service (Seenotdienst), Cherbourg, and of his visit to Dunkirk, France, and meeting with Russian Foreign Minister V.M. Molotov and opening of exhibition “Der Sieg im Westen” (Victory in the West) in Vienna, Austria. She also recorded the Göring family outdoors in the snow and formal portraits of the Göring family members, some accompanied by Adolf Hitler.

Clausen’s Die Vollendeten (‘The Accomplished’) published in 1941, was a compilation of her photographs of death masks of Beethoven, Brahms, Clemens von Brentano, Fichte, Hebbel, von Humboldt, Lessing, Luther and others which had in common, she stressed, the fact that they were “in the one word – GERMAN.”

After World War II, she relocated to Hamburg, where she had fled with her three children after the death of her husband, and though she lost her negatives to Allied bombings, she continued her photography work at various theatres, including the Hamburger Kammerspiele, the Deutsches Schauspielhaus, the Thalia Theater and the Ernst Deutsch Theater and elsewhere, covering the premiere of Wolfgang Borchert’s play The Man Outside in 1947, and as late as 1968, Samuel Beckett’s production of Endgame at the Schiller Theatre in Berlin, in dim lighting. She was an accomplished portraitist and during the 1960s trained a number of assistants including Gisela Floto, Ute Karen Walter, Fritz Peyer, and influenced many others including Irene Haupt.

Clausen’s theatre image that McHugh appropriates for Tremendum is of Marcel Marceau, from 1964.

Aylsa McHugh held her debut solo exhibition Persona at Rubicon ARI in 2019 and that was followed by Shadowlands at Incinerator Gallery (2021). Since being selected for the 2013 Melbourne Now exhibition, her work has appeared at the Tate Modern (London), Nagoya University (Japan), the Centre for Contemporary Photography (Melbourne) and the Perth Institute of Contemporary Art. Recent awards include the Hero Apartment Building Public Art Commission from the City of Melbourne (2020), the ‘Works on paper prize’ in Brunswick Street Gallery’s Fifty Squared Art Prize (2021) and the People’s Choice Prize at the Noel Counihan Commemorative Art Awards (2021). McHugh was also a finalist for the Waverley Art and Printmaking Prizes, the Geelong Gallery’s Acquisitive Print Awards and the Campbelltown Arts Centre Fisher’s Ghost Art Award, before being chosen as a finalist for the Experimental Print Prize this year. McHugh holds a Bachelor of Fine Arts (Sculpture) from the Victorian College of the Arts (2002) and is a member of the Melbourne Collage Assembly. Her work is held in private collections locally and internationally.