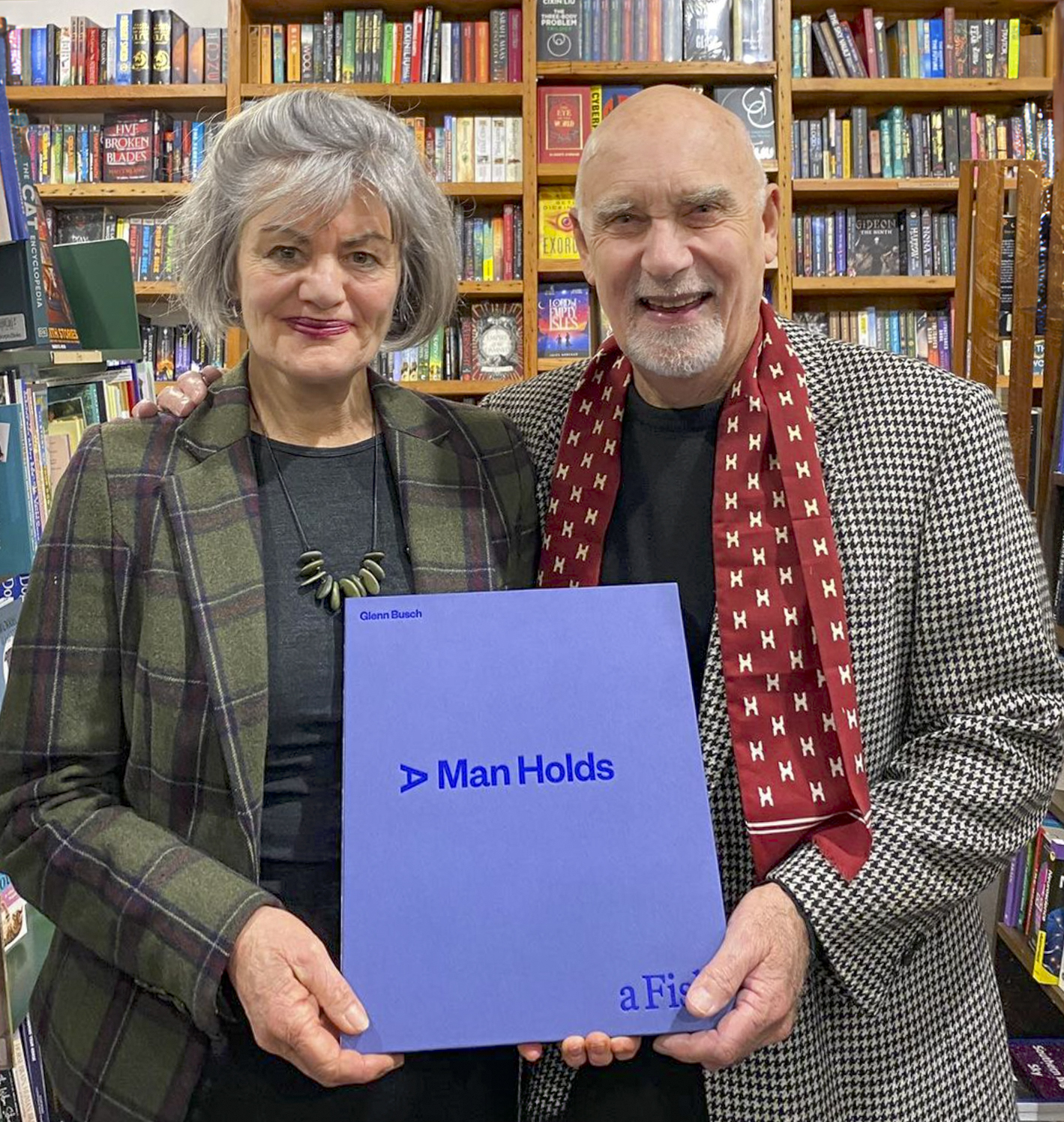

Quite some time back, Phil Quirk sent me Glenn Busch’s A Man Holds a Fish. What a gift! More than a new photography book, it is a beautifully crafted artefact and an apt tribute by Te Papa Tongarewa, the Museum of New Zealand, to one of the country’s most remarkable photographers.

Quite some time back, Phil Quirk sent me Glenn Busch’s A Man Holds a Fish. What a gift! More than a new photography book, it is a beautifully crafted artefact and an apt tribute by Te Papa Tongarewa, the Museum of New Zealand, to one of the country’s most remarkable photographers.

Born on 18 Aug 1948 in Auckland Busch is the same age as Quirk who traveled to attend the launch, and whom Busch acknowledges in the book as an Australian inspiration and friend. Like Quirk, he is a photographer of the 1970s, the period from which Phil, I, and others in our little team are assembling work and biographies from the alumni of photography at Prahran College who are currently showing at the Ballarat International Foto Festival.

The acceptance of photography as an art form in the 1960s and 1970s was advancing neck-and-neck in New Zealand and Australia, but the former had the advantage of the organisation PhotoForum Inc., formed in 1973, to which Busch was a contributor of portfolios to its magazine Photo-Forum and for its first exhibition The Active Eye: Contemporary New Zealand Photography in May 1975, and he, in conjunction with Tom Elliott and Alan Leatherby, started ‘Snaps—A Photographers’ Gallery‘, in Auckland in December 1975.

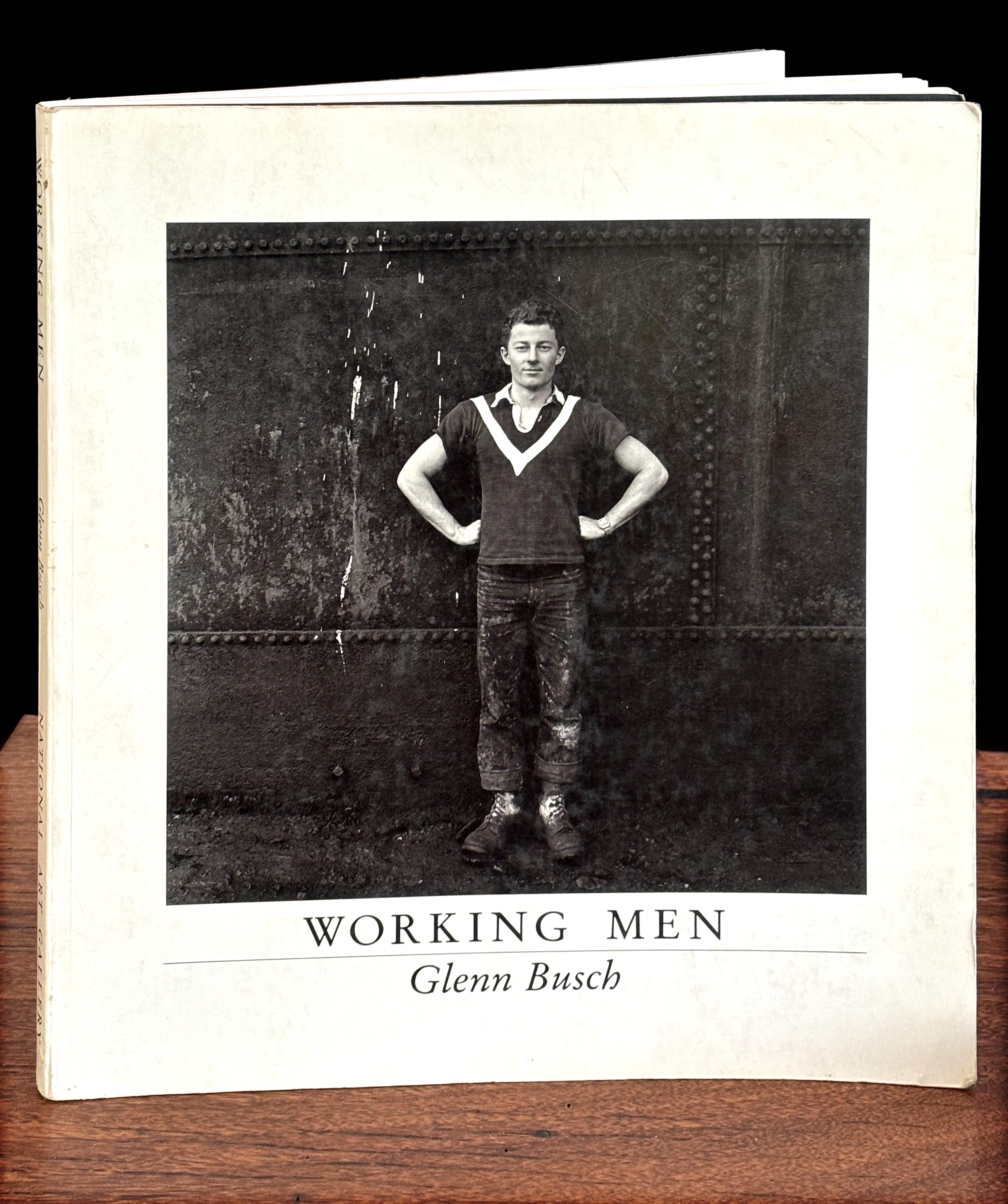

I treasure also my much-thumbed copy of another volume of Busch’s work, also published by Te Papa, 40 years ago, from an exhibition that opened at the National Art Gallery in April 1984 and which subsequently toured the country. Copies of the series are held in three major collections in New Zealand. I bought the book when it was released after seeing he was doing something I could never have done as well as he.

In my late teens in 1969 I had found myself having to work at anything I could find; driving a Baker-Boy delivery van, picking and packing in the Datsun warehouse, cutting carpet tack strips in the Roberts factory, washing the nicotine stains off the ceilings of tour buses, cleaning office ashtrays and emptying their bins, mopping and polishing, and defying vertigo while squeegeeing windows of high-rise buildings.

My fellow workers, all of them men, were friendly to me, a novice in each these occupations. Expert at what they did, they’d pass on a few tips and cautioned me to pace myself and enjoy the lunch-breaks in the sun and their jokes and stories between the bouts of quite strenuous labour. There was a welcome yellow pay packet, but most of all, I took away a respect for these friendly men. Certainly they were ordinary people doing ordinary jobs, yet each one had a unique life-story which, along with a personal philosophy, accumulated in me, ‘a good listener’, from our conversations. Their biographies would be drawn disjointedly from a dignified reticence, or in a flood of braggadocio eloquence, depending on their nature.

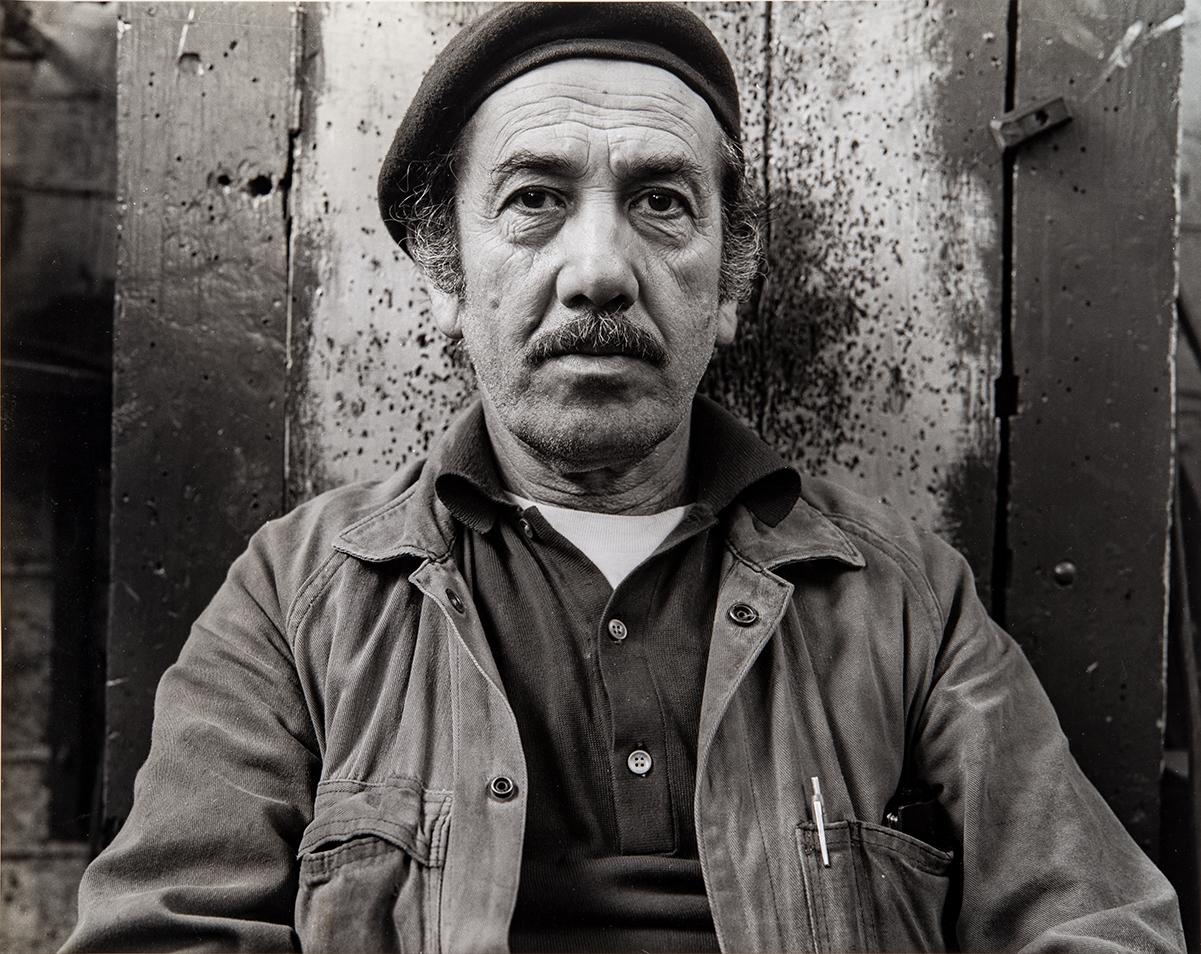

Busch’s Working Men regards such people. They are just as they look in his photographs, as we find in each subjects’ own biography transcribed on the page facing their portrait, and usually running over several sheets. Here’s a sample, as told to Busch in 1981 by Clive Mundy, a railways surfaceman in Christchurch:

“I’d say I’m just an ordinary, straight out, average New Zealand working man. I’ve never had no ambitions. Some people would like to climb up in a job and become an executive, or own a factory, or as they say, be something in life. But I’ve been the other way. I’ve been content to carry on as ordinary. I think that’s the most fulfilling of the lot in the long run, ’cause all you can really get out of life, is to wake up in the morning and feel hungry, enjoy your breakfast, and go out and see the birds in the trees, and really appreciate the sunshine as it shines everyday, try and go to a job that you like, where you can have a good talk and do your work, and feel good that you’re working. You enjoy getting your coat off and working, and then coming home, having a good tea again, reading your newspaper and listening to the news. The main thing is to have an interest in everything if you can, politics and everything, and then go to bed. You have to go to bed, you’re still full of life, but you’ve got to go to bed, to get that sleep, to be able to get up in the morning and do that work. I’m fifty-nine, and I feel about the same today as when I was twenty, yeah, exactly, in all directions, I feel just the same!

“I started as a boy, fourteen years of age, at the James’ Mine on the West Coast. Rope boy I was. They had endless steel ropes—some two miles long—that pulled the full wagons out and the empty ones back in. It was run by a big motor with a drum. Two or three years, then you get put inside and you become a trucker. That means you push the trucks in and out, to feed the miners who are on the coal face, they fill them, you just go backwards and forwards, maybe forty full trucks out and forty empty ones in…”

By giving his photographs voices Busch invites you into a conversation with them. Some of the stores are hard; several of these men fought in WW2 or Korea, and many reveal how their jobs impacted their health, something quite evident in many of the photographs. Busch recorded what I wish I had, so forced me to approach my photographs of workers in another way, but inspired, electrified, by his project.

The reason for the impact of his ‘photographic conversations’ is Busch’s own experience of labouring that was early and extensive;

“My education was limited. I left the last of the many schools I attended a couple of months before my 15th birthday and drifted around Australia and New Zealand, working in various jobs, mines, factories, sugar mills, whenever I had the need for some money. By the time I was twenty-one, I was married, I had one child and another one on the way, and I found myself living in a garage-somebody’s shed in the outer western suburbs of Sydney.”

In 1974 Busch issued a limited edition portfolio of original prints (Glenn Busch: Five Photographs, edition of 25). His subsequent Marylands Portfolio, depicting mentally and physically handicapped boys from Marylands Special School in Christchurch, rapidly sold to galleries and collectors and was collected in 1975 by Jennie Boddington for our National Gallery of Victoria.

Busch’s oeuvre is consistently in sympathy with the Humanist Photography movement, also known as the School of Humanist Photography, a social documentary practice based on a perception of social change. It emerged in the mid-twentieth-century and is associated most strongly with Europe, particularly France, which was particularly affected by the chaos of two world wars, though it was a worldwide movement. Within photojournalism it forms a sub-class of reportage, and narrative more specifically, as it is concerned more broadly with everyday human experience, mannerisms and customs, than with newsworthy events. Its practitioners are conscious of conveying particular conditions and social trends, often, but not exclusively, concentrating on the underclasses or those disadvantaged by conflict, economic hardship or prejudice. Humanist photography “affirms the idea of a universal underlying human nature”. Jean Claude Gautrand aptly describes Humanist photography as:

“a lyrical trend, warm, fervent, and responsive to the sufferings of humanity [which] began to assert itself during the 1950s in Europe, particularly in France … photographers dreamed of a world of mutual succour and compassion, encapsulated ideally in a solicitous vision.”

Busch’s combination of oral history and full-length environmental portraits achieves exactly that.

Desmond L. Kelly—a president of PhotoForum’s sister organisation in Wellington and now a crime writer living in Australia—was editor of Working Men. In his considered introduction he points to another thread to which Busch’s work seems to attach, that of the Americans, Paul Strand, Walker Evans and Dorothea Lange, and the German, August Sander, though he acknowledges that Busch “was ignorant of such examples when he began to form his own style, more than a decade ago [i.e. the 1970s]”

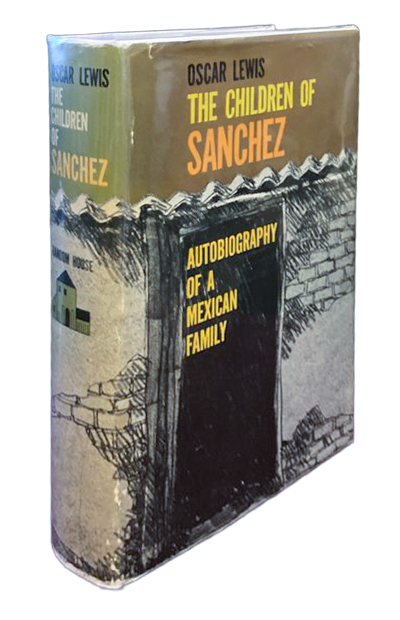

Editor Kelly also sets Busch’s 1980s work in the context of ‘reported experience’ captured through the use of the tape recorder, starting with anthropologist Oscar Lewis’s lives of Mexico’s urban and rural poor, The Children of Sanchez: Autobiography of a Mexican Family, the result of his six months in Tepoztlán in 1943-44 and return visits during the summers of 1947 and 1948, which refuted the idealising Rousseauan impressions of the poor formed by an older colleague Robert Redfield 20 years earlier. The Scandinavian Jan Myrdal, Kelly continues, was so impressed by Lewis’s work that he spent a year in a remote area of China and wrote Report From A Chinese Village from recorded conversations with the peasants of Liu Ling, all of whom had known conditions before and after the communist revolution. Kelly points out that in turn, Myrdal’s book inspired author and broadcaster Studs Terkel to interview Chicagoans and write a number of books like Division Street: America (1967), and reports that it was this work of Studs Terkel that prompted Glenn Busch to take a tape recorder with him as well as his camera, and not to a remote village like Lewis or Myrdal, but to the people around him.

However, the frequent comparison of Busch with American photographers such as Diane Arbus ceases to hold, and serves only to contrast theirs with his humanist purpose. Terkel’s Working. People Talk About What They Do All Day and How They Feel About What They Do (1972) was followed by American photographer of Suburbia, Bill Owens‘ Working : (I do it for the money) (1977). The latter brings an ironic tone to his depictions of middle America. The year after Working Men was published came fashion photographer Richard Avedon‘s In the American West (New York: Abrams, 1985), the consistent theme of which, as Richard Bolton in Afterimage argues, sees “human experience as manifested in [no]thing but style,” a quality, less sombre, but equally arch, exoticising and stereotyping that is found also in the Small Trades studio series of 1950–51 by Irving Penn.

By contrast, Busch is distinguished by his sincerity and respect in treating his subjects, quite contrary to Robert Mannion’s perfunctory review of Working Men which sarcastically chides Busch for recording “…the noble industrial savage” [New Outlook, no.11, July-August, 1984, p.45.]

As Busch points out in an email to me, the steps toward making Working Men, were evolutionary, not planned:

“I did not begin using text and image together until I started on Working Men. I’d heard that the Christchurch Gas Works was about to be pulled down and thought I should make some pictures before it all disappeared. In the time I spent there, I would often have a cup of tea or sometimes play cards at the lunch room table with the people I was photographing. After a while I came to realise that rather ironically, I was making photos of working men, but what they were mostly talking to me about was the fact that they were not to be working much longer. This in a time when jobs weren’t exactly plentiful. That is what galvanised me to use text with the images.”

Does Busch perpetuate the ‘poverty porn’— that issue raised by Susan Sontag in her 1977 On Photography (a collection of essays Sontag published in the New York Review of Books between 1973 and 1977)?:

To photograph is to appropriate the thing photographed. It means putting oneself into a certain relation to the world that feels like knowledge—and, therefore, like power. [The New York Review, ‘Photography’, 18 October 1973]

Busch recounts how he was impressed by Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-Up:

“At the time I grasped very little of the social or political implications of the film. What I did find striking was this macho photographer, played in the film by David Hemmings. If I remember correctly the film opens with him photographing in a shelter for old men, making photographs for an “art project” he is working on. To me, at the time, that seemed like cutting edge documentary— I sort of fell for that one. It’s not what I would think now, but at the time I was totally taken in by it. I also rather liked the idea—if l’m to be truthful—of all these naked young women throwing themselves at this cool photographer. The movie’s much more than that, but from where I stood at that point in time that’s what I was seeing and I suppose it looked a hell of a lot more exciting to me than working in a factory.”

HIs attraction to the medium was reinforced, and made more mature, when in back in Auckland:

“I walked into a room full of extraordinary people. Easily the most astonishing and exotic mix of individuals I had ever seen before. Artists, sailors, dancing girls, and gangsters, even labourers like myself, in this one room. One in particular really took my fancy, an enigmatic old woman, sitting at a bar, covered in cheap jewelry…Of course the people who filled this room were not actually living human beings, but portraits, superb photographs by the man now known to the world by his pseudonym, Brassai.

“To see such work in New Zealand at that time in the 1960s was, to say the least, unusual, and what happened when I saw those photographs was also unusual. I think that was the moment, seeing those pictures, unlike anything I had ever seen before in my life, when I knew what it was I wanted to do. I wanted to try to make pictures that might affect people in the same way these pictures had affected me. So changing my life that day was as simple as walking into a room.” [Brassaï: Seventy-one Photographs, 1931–1958 at Auckland City Art Gallery 17 May-13 June 1971 originated at the Museum of Modern Art, New York.]

The purpose that Busch has for his photography stands valid against the Sontag’s jaundiced perception that photographers, especially those documenting society, exploit or misrepresent their subjects. He says in the introduction to this new book A Man Holds a Fish:

“The images I have made, the various stories I have collected over time, do not belong to me – they are owned by those who have been willing and kind enough to share them. I have simply put down, as best I could, what has been told or, in this case, shown to me.”

Interviewed by Tim J. Veling in Nina Seja’s 2014 PhotoForum at 40 : Counterculture, Clusters, and Debates in New Zealand Busch clarifies his aims and approach:

“My own interest has always been about people’s lives. And I guess that’s one of the reasons why I started writing down the things that people told me, the stories that they told me. In a way, a photograph is like a little short story, one that the viewer may need to supply the beginning and the end to. Perhaps that’s why I always liked to talk to people. It’s something that I often did. I was never particularly interested in, say, the Cartier-Bresson style of photography, where people would not even know they were being photographed. I mean, I appreciate what he does, I think it’s beautiful work, it just wasn’t something I was interested in doing myself. I was much more interested in meeting people, making their image and listening to their story.”

However, Busch in his introduction to A Man Holds A Fish, in which the accounts given by his mother (“a woman who never had a problem with the word ‘exaggeration’) of his conception, and of his own birth (a near-death experience), is realistic about the nature of stories:

“Listen carefully to the stories of others and they may tell us something of ourselves. The story of any person exists first in the mind of its teller, perpetually renewing itself as, like smoke in wind, it is constantly shaped and reshaped in the flux of daily life. Narratives constructed from various facts, memories and rumours are added to, subtracted from, come together and fall apart in a continuous reassembling of experience and imagination. The human mind is a place where fact meets fiction, where reality and fantasy mingle easily and endlessly with fabrication, half-truths and invention. As they say, looking at something is no guarantee you will actually see it.”

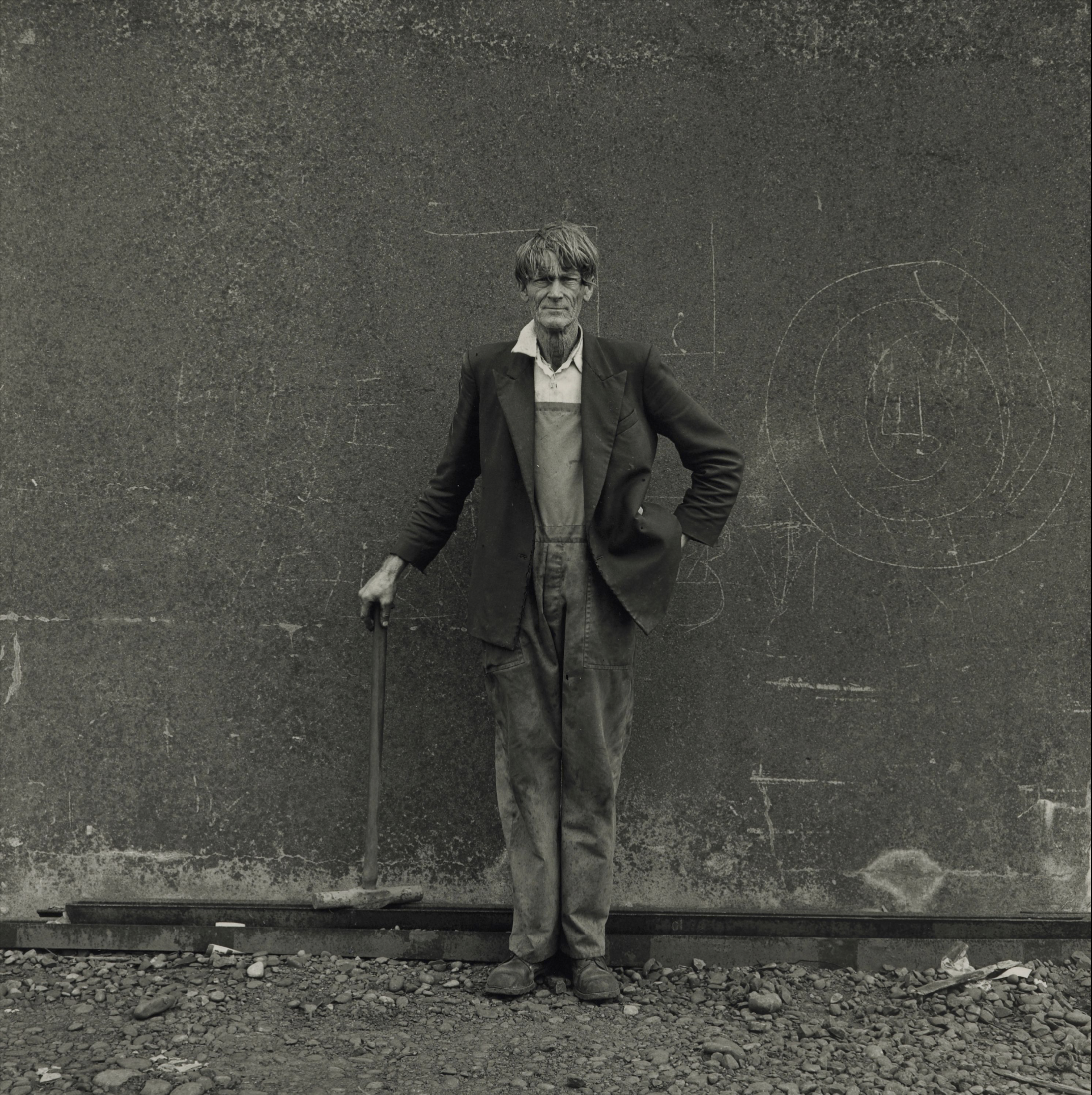

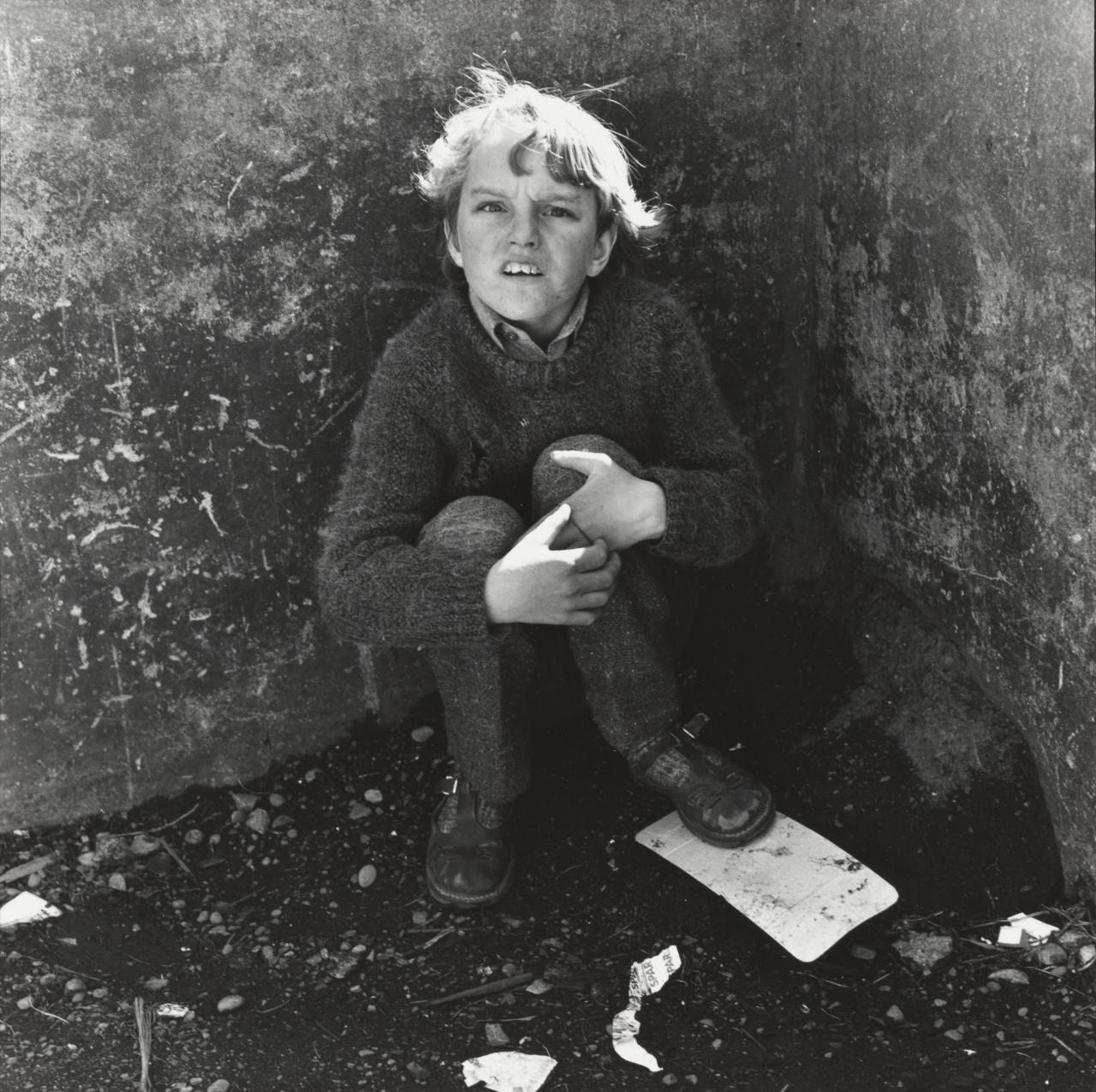

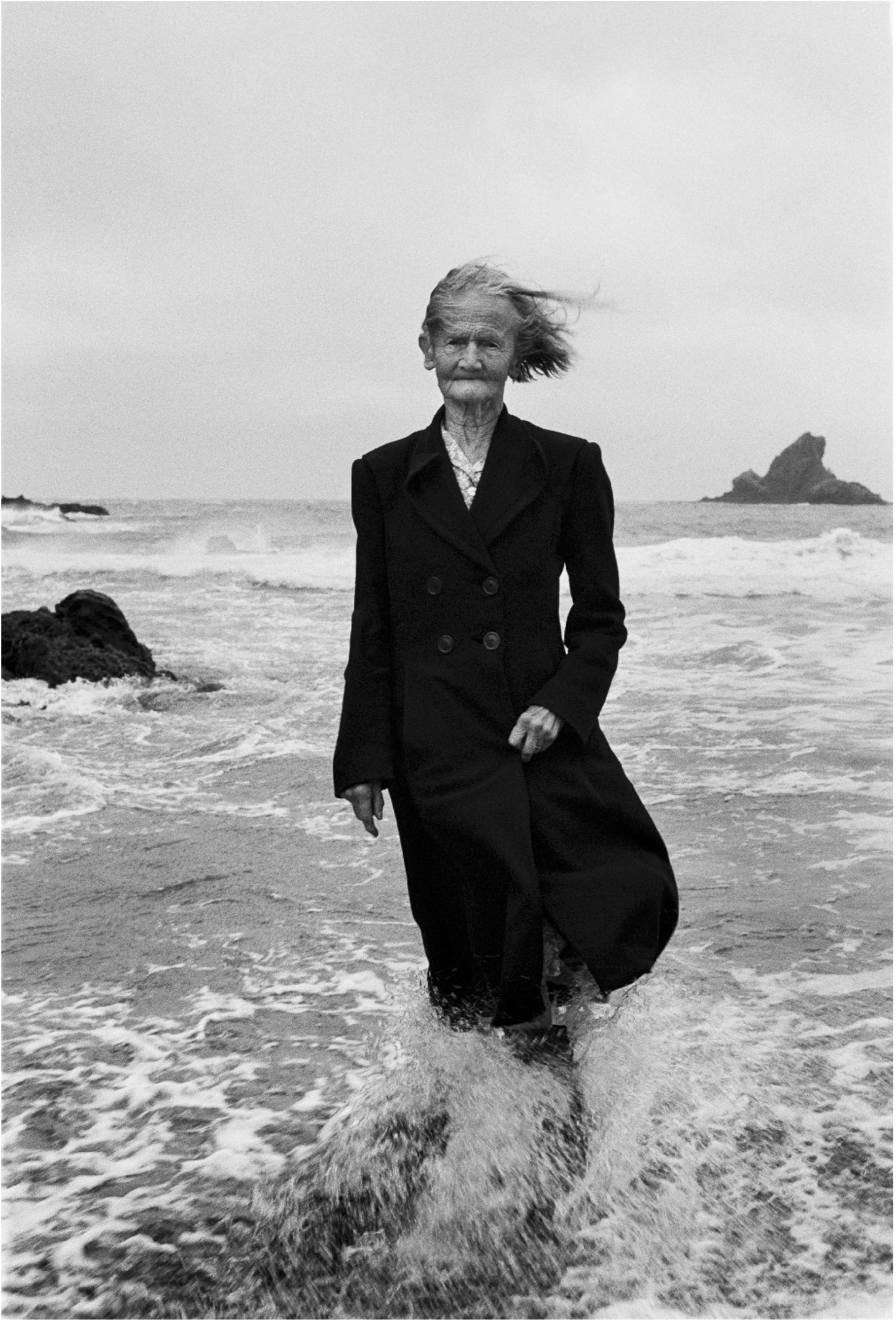

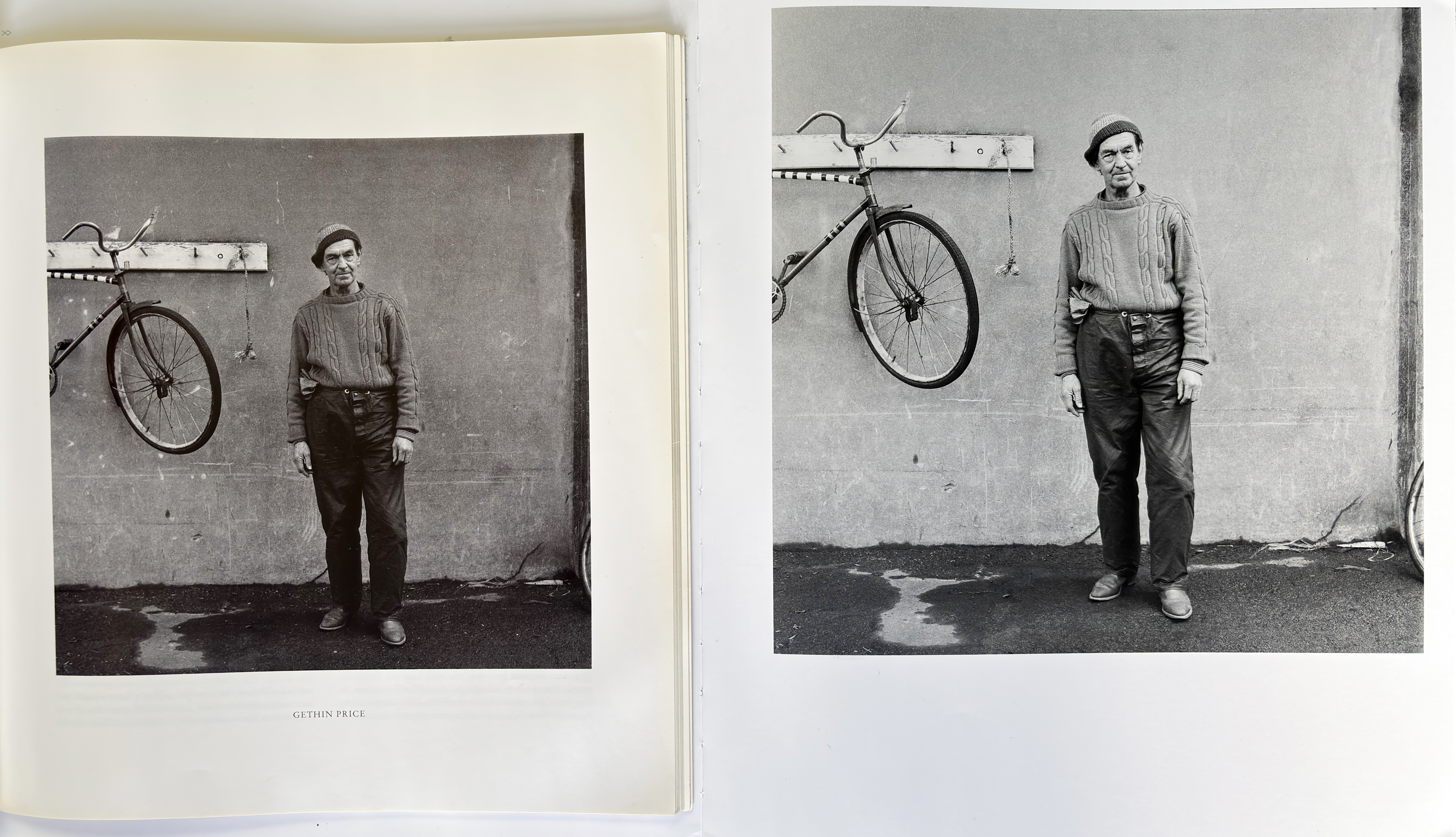

Released in August 2024, the new book features 79 portraits. Where Working Men contained 30 and all of them men, the new book expands on that original set with photographs of women and children. Where the pictures for the earlier book were made exclusively with a 120 twin-lens, square-format camera, A Man Holds A Fish includes 35mm photographs including his Woman in the Sea, Whatipú Beach, a moment that is certain to prompt you to reflect on time, age and mortality, and unexpectedly, on beauty. She might appear to repeat the mythical emergence of Venus-Aphrodite from the foam, but this is not an idealisation, we are made to realise that she is a real woman living a defiant existence which is soon to be overwhelmed.

In A Man Holds A Fish image titles and the location at which each picture was taken are given, but no dates, and the biographies that supported the portraits in Working Men are absent. Though they follow no chronology, the images flow. The stalwart figure of the woman standing fast in the surf is replaced on the next page by the bent, spent shape of a man in front of his caravan and its sagging striped annex. His head seems over-large and appears to lean dolefully into our space.

All of these pictures make the subject present to us, and in turn, they include our presence, never in a confrontational way, but as a conjunction of lives, because Busch brings us with him to the places in which these people exist. We can orient ourselves within their surroundings—their ‘backgrounds’ both physical and biographical. However scant these may be in the image—spots of blood, a scrap of wallpaper perhaps—we are impelled to scan these marginalia to discover clues about the subject, usually a single person. Examine this portrait of a lone woman in a bar in the Western Australian mining town of Kalgoorlie and you find another Venus, a pin-up girl, on a calendar in the hatch behind her.

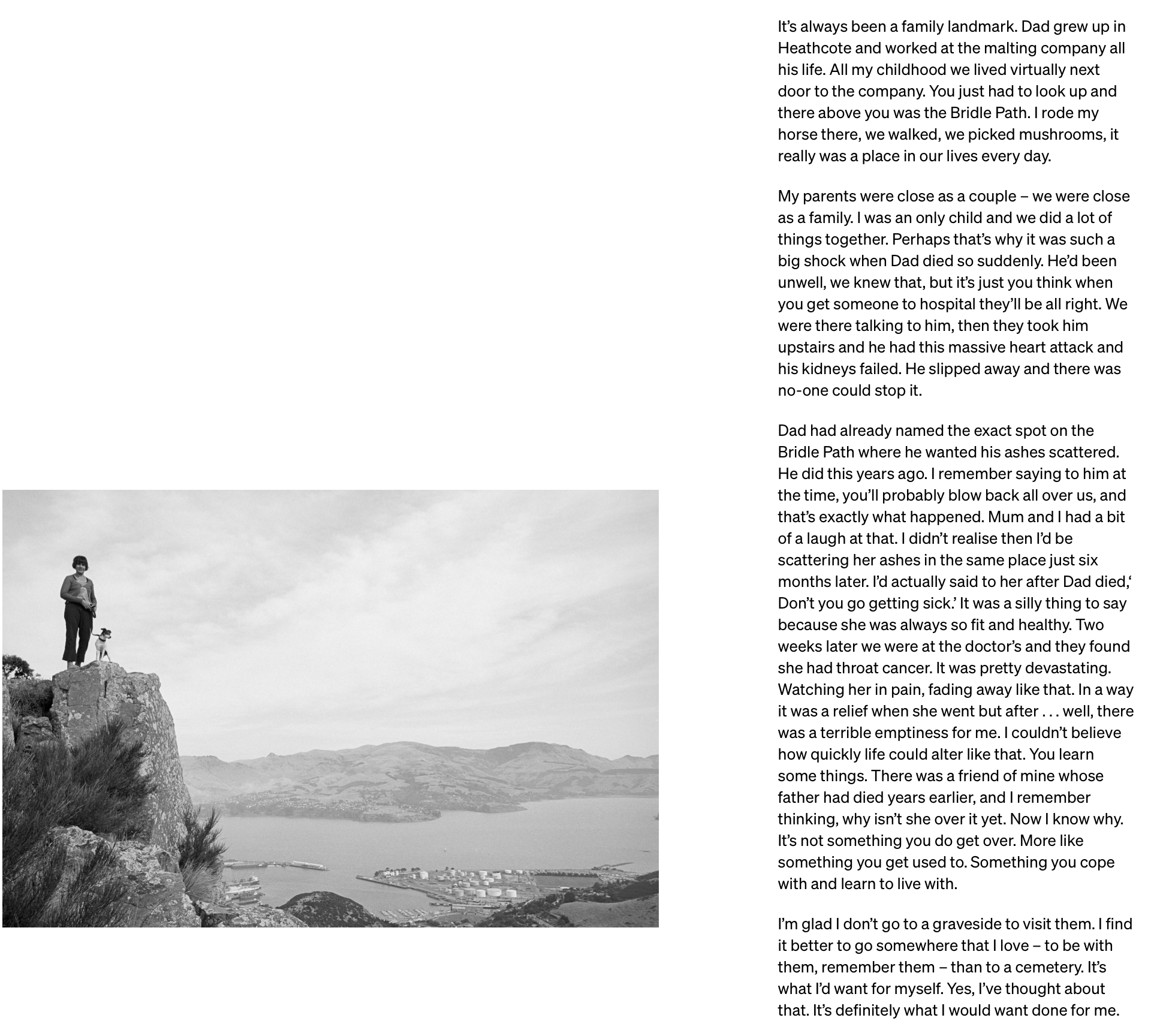

This ethos was behind the ongoing ‘Place In Time‘ documentary project with Tim J. Veling, Hanne Johnsen, Uiga Bashford, Bruce Connew, Maria Buhrkuhl, and Dean Kozanic. Busch, when he was senior lecturer at the School of Fine Arts, University of Canterbury, instigated the project which grew out of his own documentary practice, and from 2000 directed its recording of the city of Christchurch and a cross-section of its people through photography, oral history and documentary writing..

The research put these questions to its subjects;

- Where is it that comes to mind when you are asked to think about a place that is significant to you?

- What makes one place more important to you than another?

- What is your connection with this place and what is it that continues to make it important in your life today?

In each of the portraits made throughout Busch’s career, the subject provides a non-verbal response to those questions.

“In front of me now is a man with Stalin’s moustache but not his face. He wears a European cap over a shy, gentle expression. He has kind, shining eyes and holds a large fish. ‘Take a picture of this, he says, happy and a little bashful at the same time. I raise the camera to my eye and do as I am told.

“Later, in a darkroom under a dull red light, I watch hopefully for that moment of magic as the image slowly emerges in its tray of developer. ‘Yes, I tell myself, feeling happy and surprised at the same time. In front of me is the first picture I have made that seems to say something all by itself; the story of that moment, shimmering in the liquid. A picture made of silver, light and shadow. Hinting at the future, suggesting the past. His, and perhaps mine also. Today, apart from my family and friends, it has become that thing which is most important to me. Indeed, from that time on, I became a maker of images, a gatherer of stories. My work, as I think of it, has been to preserve the stories, or, in the case of the book in front of you, the images, of people I have met along the way. To put down what I have seen in the best way I could. In doing so, I have tried to be honest with those who have shared the experience with me. Mostly they are small stories, or perhaps part of a story; a view of possibilities that requires the viewer or reader to reach inside themselves for a beginning or an end.

“Once, a long time ago and full of the naivety of youth, I thought this to be enough. Now, older and more aware of the complexity of life, I am less certain. What once seemed to be whole now seems more like, well, fragments. Fleeting moments held now for a time in tiny particles of silver or ink. What I have become more convinced of are the things my father taught me: the durability of the human spirit, and the true kindness of strangers.”

That quality of silver is made present as we turn the pages of A Man Holds a Fish through its printing which includes a pass of silver ink. Tilting the book the reader experiences a depth not unlike the embedded halides of a silver gelatin print. That extended tonal range is dramatically evident when comparing the two Busch publications…

Critics emphasise the book’s design, which intentionally pushes boundaries with its stark, minimalist layout, and exposed binding that echo the themes of marginalisation captured in the photos, but it’s the use of metallic silver ink that symbolises Busch’s epiphany he experienced as he developed the titular photograph, and which further enhances the visual storytelling.

Busch’s reputation as one of New Zealand’s most influential photographers is cemented in this work, with the many reviews it has attracted lauding the “striking humanity” of his images. His ability to create intimate, unadorned portraits that bear repeated viewing has been highlighted as a key strength. This collection not only introduces new audiences to his work but also serves as a retrospective on his career’s impact on New Zealand’s photographic history.

Writing in 1975 in New Zealand’s literary magazine Landfall, Glenn Busch, with Larence Shustak and John Orbell, outlined their vision for seeding documentary photography development through a state-funded ‘Photographic History Unit’ distinct from the role of the the Department of Tourism and Publicity:

“[P]hotographers can become the historians of the present… By taking… photographs we will develop a series of images that will show the very life processes of this country, for all its people now, and to come….”

This has found some realisation through the work of his students, David Cook and Julie Riley, as well as in his own 1991 publication, You are my darling Zita. Busch and his protégés stand out as unique figures in the art world who have earnestly attempted to merge images and text within photographic books to conduct sociological inquiries.

This book has that focus, documentary as art:

“This publication came about because a few years ago I made a one-off book, a collection of images I liked, and it was this that Nicola Legat happened to see and decided to publish. As you say, art, presented in a book.” Glenn Busch

A glorious posting James = wonderful writing and research, powerful photographs

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Marcus…marvellous to have your wise encouragement!

LikeLike