In its development the panoramic photograph was to exceed the limits of the human field of vision to encompass what we can only see by turning on our heads; can we make it art?

In its development the panoramic photograph was to exceed the limits of the human field of vision to encompass what we can only see by turning on our heads; can we make it art?

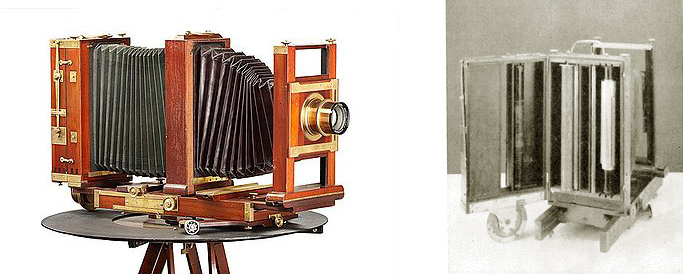

To take up where we left off in this series of posts on the photographic panorama, It was the advent of gelatino-bromide film in the 1880s, and cameras that could exploit its flexibility, that enabled the production of a 360º panorama in the one take.

The most significant was, in 1890, Jules Damoizeau‘s Cyclograph in which a clockwork motor rotates the camera and the same mechanism thus activates the unrolling of the film in opposite direction. On 30cm wide film, 3.1 metre panoramas of great clarity could be made with a 500mm lens.

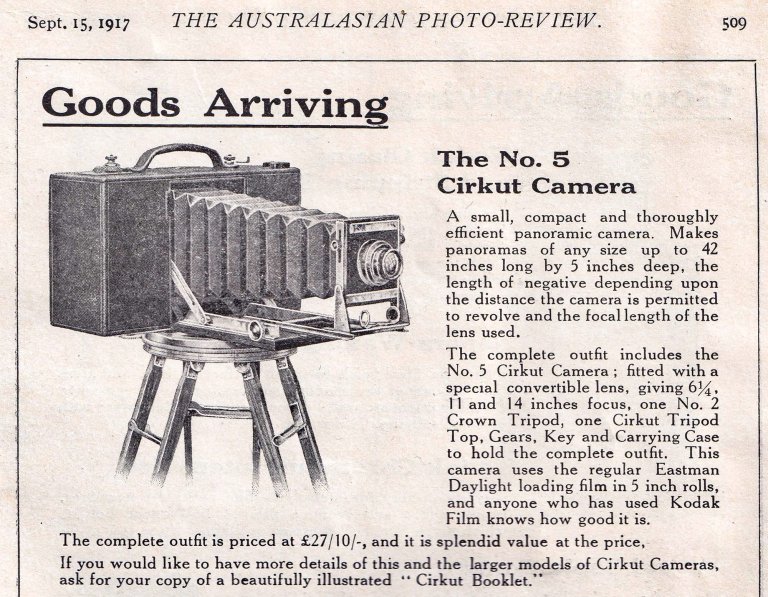

Only a few were sold, but it proved the principle used in the more commercially successful Cirkut of 1904, which remained in production in various models (named after the film width in inches up to Model 16) until 1949. Capable of image resolutions that are breathtaking even by digital standards, it is still in use.

Using a characteristically unique approach in 1895, Ducos du Hauron (1837–1920) discovered the principle of the Microcosme. His patent of May 1895 decribes a “Curved mirror apparatus providing by anamorphosis and without a rotating mechanism a correct panorama …” The 360 ° image from around a spherical mirror placed horizontally is captured by a lens which projects it vertically onto the inside of a cylinder lined with film; it is thus deformed a second time to appear straightened and in the right proportions on the internal walls of the cylinder…ingenius!

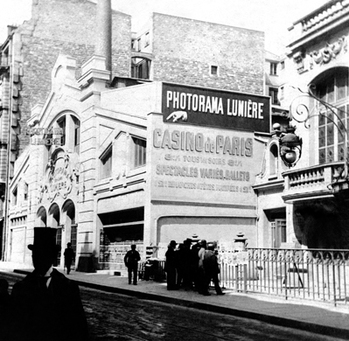

In 1899, Louis Lumiere invented the 360º Périphote cylindrical camera and exhibited to large audiences via projection into a screen which encircled them, above their heads; a spectacle, and the device it employed, he called the Photorama.

Lumière applied certain principles of the shuttering of the Brothers’ more famous Cinematograph; Instead of the fixed systems experimented with until then: the uniform projection of the whole of the transparency on a fixed cylinder around which a plate holding 12 lenses rotates at 180 revolutions per minute (3 revolutions per second). This “scanning,” through “retinal persistence” fuses 12 projected portions of the image onto the circular screen into a single continuous image, thus avoiding aberrations resulting from the rendition of a curved surface by fixed lenses if several juxtaposed and clumsily joined images were individually projected.

This was to be the answer to the vogue for the panorama and diorama of the turn of the 18th century, reinvented in modern, photographic form. Dozens of shots could be presented quickly and consecutively at a huge 6 metres high, rather than one static painted panorama. Hundreds of photographs measuring 8.7 x 63 cm were taken by Lumiere’s Périphote.

A precursor of the much later ‘Cinérama’, but a more ambitious attempt at virtual reality, it failed because of the competition of Louis’s, and his brother’s, own invention of the cinema; audiences were probably disappointed that the Photorama did not show moving pictures.

Operating the “Salle du Photorama” installed rue de Clichy in Paris in February 1902 proved too expensive, and despite the extraordinary technical prowess applied to the problems of the mass viewing of panoramas, and the gigantism of the representation, the theatre closed its doors after the second season, in the spring of 1903; attendances did not quite live up to expectations and the Cinematograph prevailed.

Even though panoramic cameras had existed as early as Friedrich Martens’ Megaskop-Kamera in 1845, they became broadly accessible only in the 1890s, a major obstacle being the use of flat glass plates incompatible with the design of such cameras. The invention of roll film in the 1880s, and the consequent popularity of Kodak’s pre-loaded box camera, was followed by the easy-to-operate, mass-produced Kodak Panoram camera, introduced with commercial success in 1900. The Panoram camera permitted, as Eder notes “an instantaneous exposure over an extensive field of vision by an analogous turning of the lens and by a slit shutter passing in front of the film.” It was first shown at the 1900 Exposition in Paris and competed successfully with the Al-Vista of similar design introduced in 1898.

Kodak ‘Brownie’ designer Frank A. Brownell was responsible for the camera patent and released a series of models, about the size of a shoe-box and which could be hand-held for shooting landscapes. Kodak described it as “a camera of few parts. Its operation is very simple and good pictures will be obtained from the beginning.”

The No.1 captured 120º field of view, and produced negatives 5.71 cm x 17.78 cm. Model 3A used the 6-exposure 122 sized film roll for 3 shots and the 10-exposure roll for 5. The No.4 encompassed 142º on size 103 negatives,[15] each frame being 8.89 cm x 30.48 cm. Panoram models sold for US$8 and US$26 for No.1 and No.4 Panoram models respectively (equivalent to about $252.26 and $819.86 in 2021), not much more expensive than the Folding Pocket Kodaks.

This is the camera used by Australian-American photographer Robert Vere Scott whose landscapes of my home town Castlemaine, and recently acquired by our Art Museum, have prompted this series of posts on the panorama format. In particular I was impressed by his vertical panorama of Barkers Creek, which could not be made with the Cirkut camera that Scott also used, because the construction of the latter meant it could not be operated on its side to take a vertically oriented panorama. How, I wonder, was he inspired to use his camera in that manner, and for artistic, rather than topographical purpose? An advertisement for the camera, and its manuals, but after 1910, indicate that Kodak’s marketing department did envisage such an application, though perhaps they were prompted by photographers own creative uses of it?…

“In addition to its use for making horizontal pictures, the camera may be as easily used in the vertical position, and decidedly unique pictures of high waterfalls, mountain peaks and such subjects can be secured.”

…and…

“When held vertically, most artistic panel pictures are obtainable, such as waterfalls, mountains. etc.”

Were photographers other than Scott in the Antipodes, who seems unlikely to have been noticed by Kodak, originating this idea?

To understand why “panel pictures” should be “artistic” we need to look to Japonisme, the influence of Japanese traditional styles on emerging Western art after the late 1850s, in Impressionism and Fauvism in Europe and the Aesthetic Movement in England which adopted its innovative compositional devices. Out of this arose Art Nouveau, with which Pictorialism shares stylistic characteristics.

The tall and narrow vertical format of 18th century Hashira-e, Japanese woodblock print that was often hung or pasted on pillars for decoration, even though it had been replaced in Japan by the compositionally less challenging Oban tate-e format, inspired turn-of-the-century American Pictorialist photographers the Photo-Secession group. In England the Brotherhood of the Linked Ring was founded in 1892 and its members counted the Americans Alfred Stieglitz, Rudolf Eickemeyer, Jr., and Clarence H. White. The Photo-Secession prospectus of 1905 features such an image of a silhouetted photographer in moonlight (the Whistleresque nocturne being another favourite motif).

In France at the end of the century, Pictorialism developed among amateur circles; the Parisian Photo Club was formed earlier than either the English or American groups in 1890 by Constant Puyo, Robert Demachy, L. Hachette, Paul de Singly, and René Le Begue and four years later they organized their first ‘Exposition d’art photographique’ in rue des Mathurins in Paris. In 1896 Puyo wrote Notes sur la Photographie Artistique. In 1899 Robert de la Sizeranne published his manifesto, asking rhetorically; La Photographie est-elle un art? In 1903 Puyo launched La Revue de photographie in which photographs from Photo Club exhibitions were published, whose members kept up with pictorialists abroad and participated in foreign exhibitions and publications.

Part of the Pictorialist aesthetic is to exploit optics to obtain the notorious “blurriness” which characterises this artistic movement. In England Peter Henry Emerson practiced from a conviction that the photograph should be a true representation of that which the eye saw with one area of sharp focus while the remainder was unsharp. The technique he promoted in his publication Naturalistic Photography for Students of the Art (1889) involved using a wide-open aperture to create a shallow depth of focus along with tilting of the lens panel (now commonly known as ‘tilt–shift’ photography). He advanced on this in 1890 with a lens that he commissioned from his friend, lens maker Thomas R. Dallmeyer, employing its aberrations to mimic the characteristics of the human eye.

Though Emerson’s work was not translated into French, the Photo Club, though they also practiced carbon printing, gum bichromate, bromoil and photogravure etc., were interested more than other Pictorialists in direct optical effects by the use of calculated design to defeat the ‘naturalism’ of ‘straight’ photography, the motif at the moment of exposure, building a true stylistics of perception, rather than rely solely on printmaking techniques.

In their empirical use of various ‘imperfect’ optics such as spectacle lenses, or by deploying telephoto lenses at close range they sought, unlike Emerson, to achieved artistic effect rather than to realistically mimic human vision.

From 1902, Leclerc de Pulligny, specialist in optics linked to the Photo-Club of Paris, was interested chromatic aberration of simple optics called “anachromatic” because they are not corrected, unlike advanced so-called “achromatic” objectives. Hermann von Helmholtz had showed that the human eye is itself affected by this “imperfection”. By not correcting chromatic aberration, the photographer — even though limited then to monochrome — obtains a resulting “chromatic blur” in which the image is surrounded by a faint halo.

Étienne Wallon, professor of physics and photographer, also present at the Salons of the Photo-Club in Paris, alerted the members to a further repertoire of optical aberrations; spherical aberration, astigmatism and distortion, though his interest was in identifying them as defects against which opticians fight.

Puyo and Leclerc de Pulligny realised that Pictorialism could profit from them: “Let’s try to see if these aberrations would not be available to art as aids […]; the simplification of surfaces without manual retouching, what we were looking for, chromatic aberration gives us. It is therefore a useful agent.” Their usefulness is the greater as the effects produced will enjoy the legitimacy of scientific calculations in design and to thus develop a repertoire of artistic means.

Puyo and Leclerc de Pulligny therefore set out to make optics with calculated aberrations, promoted in Les Objectifs d’Artiste, “artist’s lenses”; the artist not only invents his own tools, but then calls for their manufacture and marketing. The results appear at the Salon of 1904.

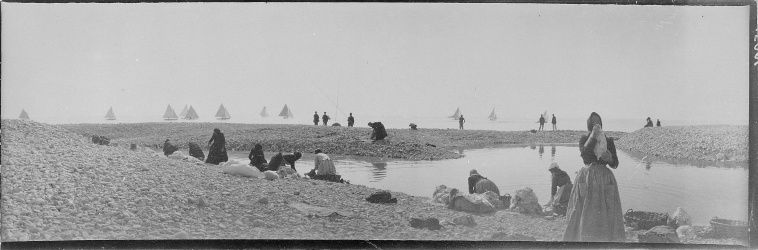

Undoubtedly it is out of such interests Constant Puyo showed horizontal and vertical panoramas and though I can find no source that specifies that he used a Kodak Panoram, the several images dating from 1900 in that format in the Musee d’Orsay are contact prints in the exact dimension of negatives from a Panoram Model 4; 6cm x 18 cm.

These predate Puyo’s enterprise in marketing ‘lenses for artists’, but I believe they should not be overlooked as an early Pictorialist essay. Distortion is certainly apparent, in that the viewer’s visual field is stretched. The rarer vertical examples are radical in their graphic, Art Nouveau exaggeration, and the Italian landscape near Mala (left) is especially ‘Japonaise’ in spirit.

We, with ready access to a panoramic format on our smartphones, have more ample opportunity to experiment with in its aesthetic potential, and not to neglect the challenge of Hashira-e and the ‘panel’ ratio.

![Alfred Stieglitz Spring Showers - the Sweeper [Camera Notes] 1901 Photogravure 15 × 6.3 cm Philadelphia Museum of Art Gift of Carl Zigrosser, 1966 Alfred Stieglitz (1901) Spring Showers - the Sweeper [Camera Notes] 1901 Photogravure 15 × 6.3 cm Philadelphia Museum of Art Gift of Carl Zigrosser](https://onthisdateinphotography.files.wordpress.com/2021/05/alfred-stieglitz-spring-showers-the-sweeper-camera-notes-1901-photogravure-15-c397-6.3-cm-philadelphia-museum-of-art-gift-of-carl-zigrosser-1966.jpg?w=191&resize=191%2C474&h=474#038;h=474)

![Alfred Stieglitz Spring Showers--The Coach [Camera Notes, vol. 5] 1901 Photogravure 13.7 x 7.3 cm Philadelphia Museum of Art Gift of William Innes Homer, 1986 Alfred Stieglitz (1901) Spring Showers--The Coach [Camera Notes, vol. 5] 1901 Photogravure 13.7 x 7.3 cm Philadelphia Museum of Art Gift of William Innes Homer](https://onthisdateinphotography.files.wordpress.com/2021/05/alfred-stieglitz-spring-showers-the-coach-camera-notes-vol.-5-1901-photogravure-13.7-x-7.3-cm-philadelphia-museum-of-art-gift-of-william-innes-homer-1986.jpg?w=250&resize=250%2C474&h=474#038;h=474)

Hi again Nikolai, I should’ve alerted you to this site years ago (maybe I did?) but I think it’s very good. Until about three or four years ago Mcardle was putting one of these out EVERY day, but he decided to retire a bit, and they come out infrequently now – maybe one a fortnight, but sometimes they bunch up. He has a fantastic fund of knowledge and writes very well. I’m sure there’ll be an accessible back-file. But, there’s still only 24 hours in a day and your time is probably already scarce.

Cheers

P

On Mon, May 17, 2021 at 12:34 AM On This Date in Photography: by James Mcard

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Peter – though your message was intended for Nikolai, I am taking the liberty of including it here since your words are so kind!

LikeLiked by 1 person