The many books published by Andrew Chapman, including The Shearers (2006), Woolsheds (2011), Around The Sheds (2012), Working Dogs (2013), The Long Paddock (2014), The Farm (2016), Woolsheds, Volume Two (2019) Quilpe (2017), and his contributions to Beyond Reasonable Drought (2009), Beyond Age (2010), Manangatang (2011). Camperdown and Its Cup (2014), Just Like Family (2015) They’re racing At Manangatang (2018), The Mallee (2020), The Wimmera (2021), The Western District (2025), convey an impression that his interest lies in Australiana.

The Australiana Society defines that as “objects relating to Australia and its history and culture”, though the gamut of Chapman’s imagery in these books (and his contributions to many more publications) encompasses more of the nation; the places, their climate, the people, their lives and livelihoods.

Andrew has a passion for rural life and a love of the Australian bush, inbred no doubt from his upbringing as the son of John L. Chapman, export manager at the Australian Wheat Board, while his interest in narrative may have been instilled by his mother Elizabeth (née Stubbings) a writer, though his storytelling is visual.

In his representation of the essential Australia he joins a lineage of such classic photojournalists—including his own idol Jeff Carter—with David Beal, Michael Coyne, David Moore, Harold Cazneaux, Max Dupain, Rennie Ellis,Helmut Gritscher,Frank Hurley,Robert McFarlane, Axel Poignant,Wolfgang Sievers, Wesley Stacey, Mark Strizic,Richard Woldendorp and many others, including Brian McArdle.

Furthermore, from 1998, in his desire to rekindle the tradition of documentary photography, and through his partnerships with, and mentorship of, like-minded photographers, Chapman founded MAP – Many Australian Photographers, its title later simplified to ‘MAP Group’, of which he was the inaugural president. One project the group undertook resulted in a widely viewed exhibition that toured the country for 5 years, and a 2009 publication, Beyond Reasonable Drought, recording global warming-induced drought across Australia.

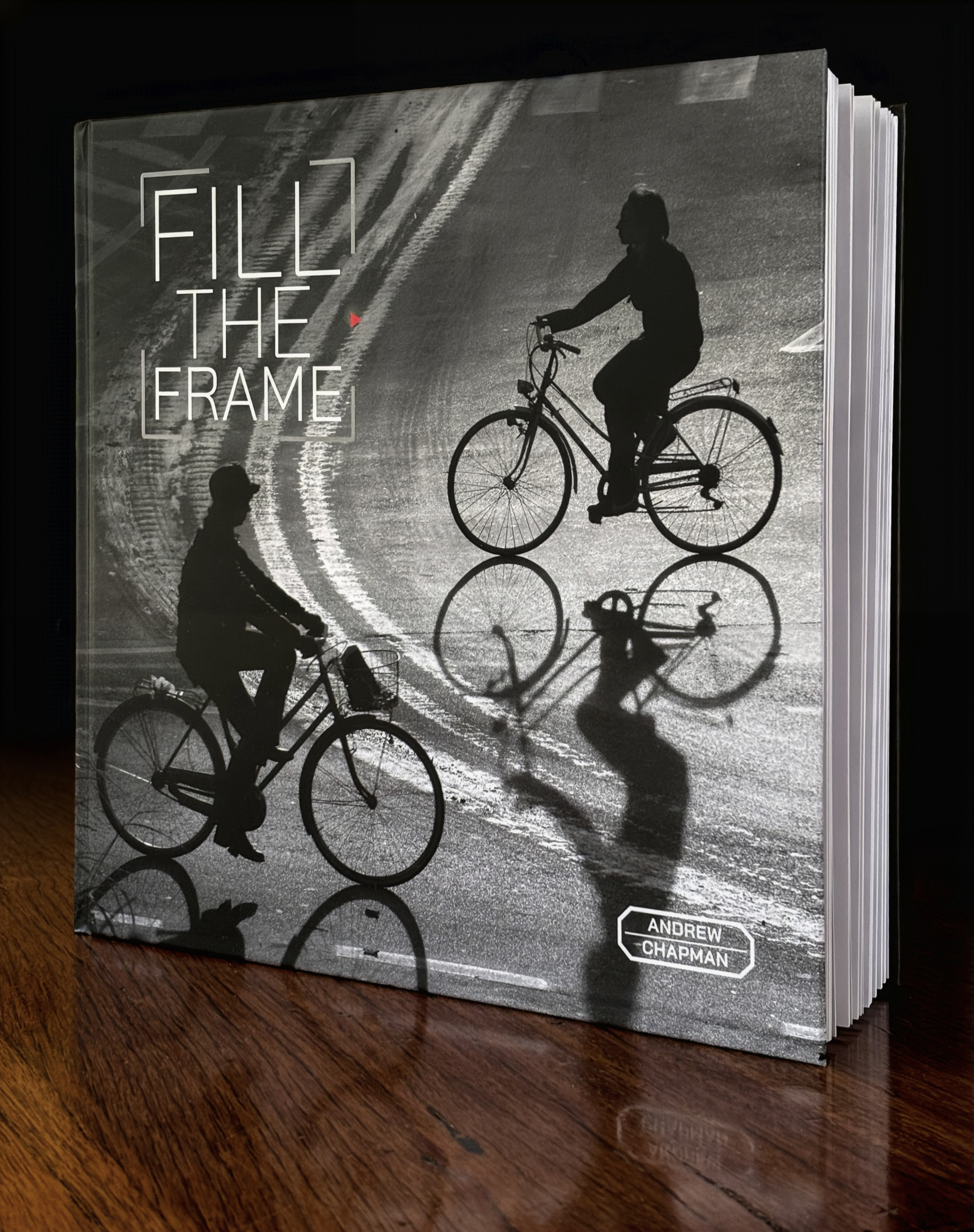

However, his new book diverges from a concentration on such subjects as shacks, sheep, sheepdogs, shearers, sheds, shooters, shows and shelter belts, to concentrate on the photographer himself and photography, specifically to discuss the genres of photojournalism and documentary. The cover picture of two cyclists in Lucca, Italy, dispenses with any connection we might make with Australia, and both that and the title draw attention instead to image-making.

The title of the book immediately reveals its generosity, This is a late-life reminiscence of a full career. Andrew, after his own brushes with mortality and now conscious of a shorter span left, offers his work as examples of the successful protocols—self-talk really—that guided his photojournalism, ‘fill the frame ‘ being one of these imperatives. This then is a book for the experienced photographer who will appreciate seeing the proof of such principles, while the novice will benefit from his distilled wisdom. That may sound ‘preachy’ but Chapman’s self-deprecation—very Australian—ensures that it is modest; earnest with a grin. Andrew accompanies us as we turn over these big, beautifully reproduced images.

It is broadly a biography recounted in pictures, but is not strictly chronological. Instead many pairs of images are allowed to speak to each other as much as the photographer speaks to them—and himself—remembering.

Andrew brielfy introduces, in ‘The Light-Bulb Moment’, his young self as restless and aimless, until photography was suggested to him by a friend, and it, in turn, led him on an odyssey full of constant challenges and encounters with personalities, whether they be those who wrestle the Golden Fleece from the sheep’s back or those who sail the skies, lofted by fire, or who restore life in the operating theatre.

Bookends to this series of themes are introductory essays ‘Documenting Life’ by photojournalist Michael Coyne, and I write ‘On the Images’; then Alan Attwood, editor of The Big Issue, formerly New York correspondent for The Age and The Sydney Morning Herald completes an admiring, beautiful closing tribute to an “unstoppable talent” in ‘The Man Behind the Camera’.

Chapman’s capacity to breech the facades amongst personae from the ordinary to the extra-ordinary, is demonstrated, for instance by his sitting us in front of beer glasses, on opposite pages, beside a lone old woman in a Prahran pub, and one held by Bob Hawke before, with a supreme force of will, the trade unions organiser gave up the booze to become Prime Minister. Thus a Labor politician and an ‘Aussie battler’, of the working-class he championed, face across the bar-room. It is just one of example of the design genius of designer Anna Wolf, which is found throughout this book and other Ten Bag Press books by Chapman.

Direct comparisons like that of Bob and the battler: a caged duck in a pose not dissimilar to that of three waiting people opposite; young and old wearing military medals on Anzac Day; and front and back views of Tony Abbott; soon give way to a more sequential thematic order. In each case the layout sets up the visual material to engage with the brief captions, and Andrew’s accompanying commentary. I write this on the train with neither the book, nor Andrew himself, in front of me, so vividly does the content of this volume, once seen, come to the mind’s eye.

In the chapter ‘Finding My Way’, Chapman reflects on his restless youth and early uncertainty as a photographer. His energetic, scattered personality and developing practice that moved sideways instead of straight ahead, though in this early period he finds seeds of later themes. First feeling inadequate against peers whose dedication and stylistic clarity seemed unattainable, subsequently working in newspapers did teach him discipline and a sense of self-worth, and gradually brought direction. Chapman likens photographers to the “ultimate collectors,” gathering images obsessively once a thread appears, amassing disparate images that eventually cohere. The chapter is an honest account of youthful bluff, insecurity, and the slow emergence of a personal voice—an acknowledgement that most photographers, even those who seem assured, likely travelled the same halting, uncertain path.

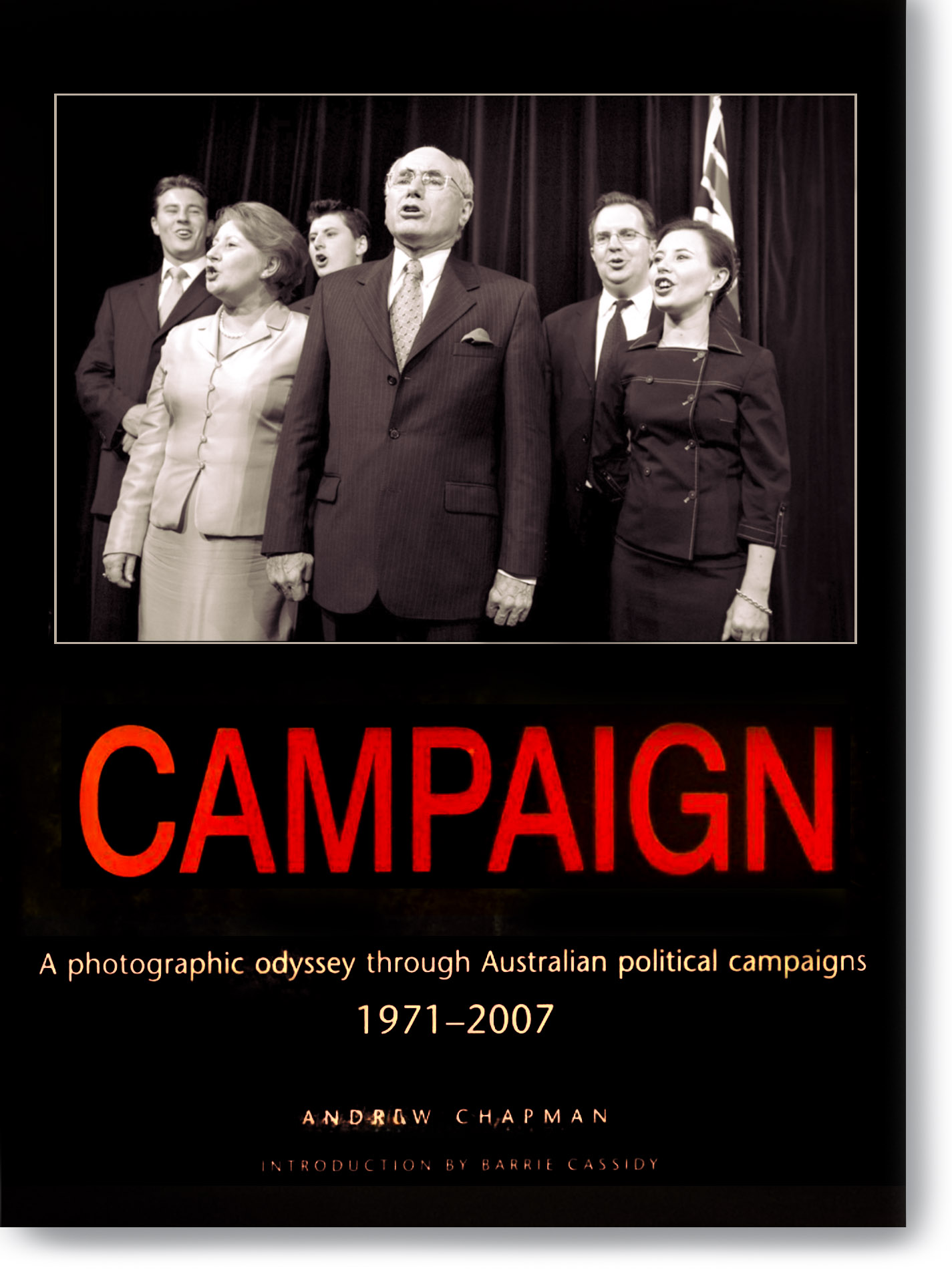

In developing a ‘Political Vision’ Chapman admits his political awareness only came with the Vietnam War, when he and many of his generation resisted conscription and feared the dystopian futures imagined by Orwell and Huxley. Gough Whitlam’s 1972 election was transformative, and the dismissal of 1975 left an indelible sense of injustice that set Chapman’s political perspective. His first political photographs involved simply showing up: attending the Vietnam Moratoriums, or slipping into Her Majesty’s Theatre during a lunch break to photograph Whitlam and Hawke in 1978. This was a time when political access was open, leaders were less managed, and candid moments were possible—conditions that gradually vanished as party control tightened from the Keating era onward. Although now more “mellowed” and disenchanted by the state of political debate, Chapman remains shaped by those early years, noting that perhaps politics has not changed as much as he has.

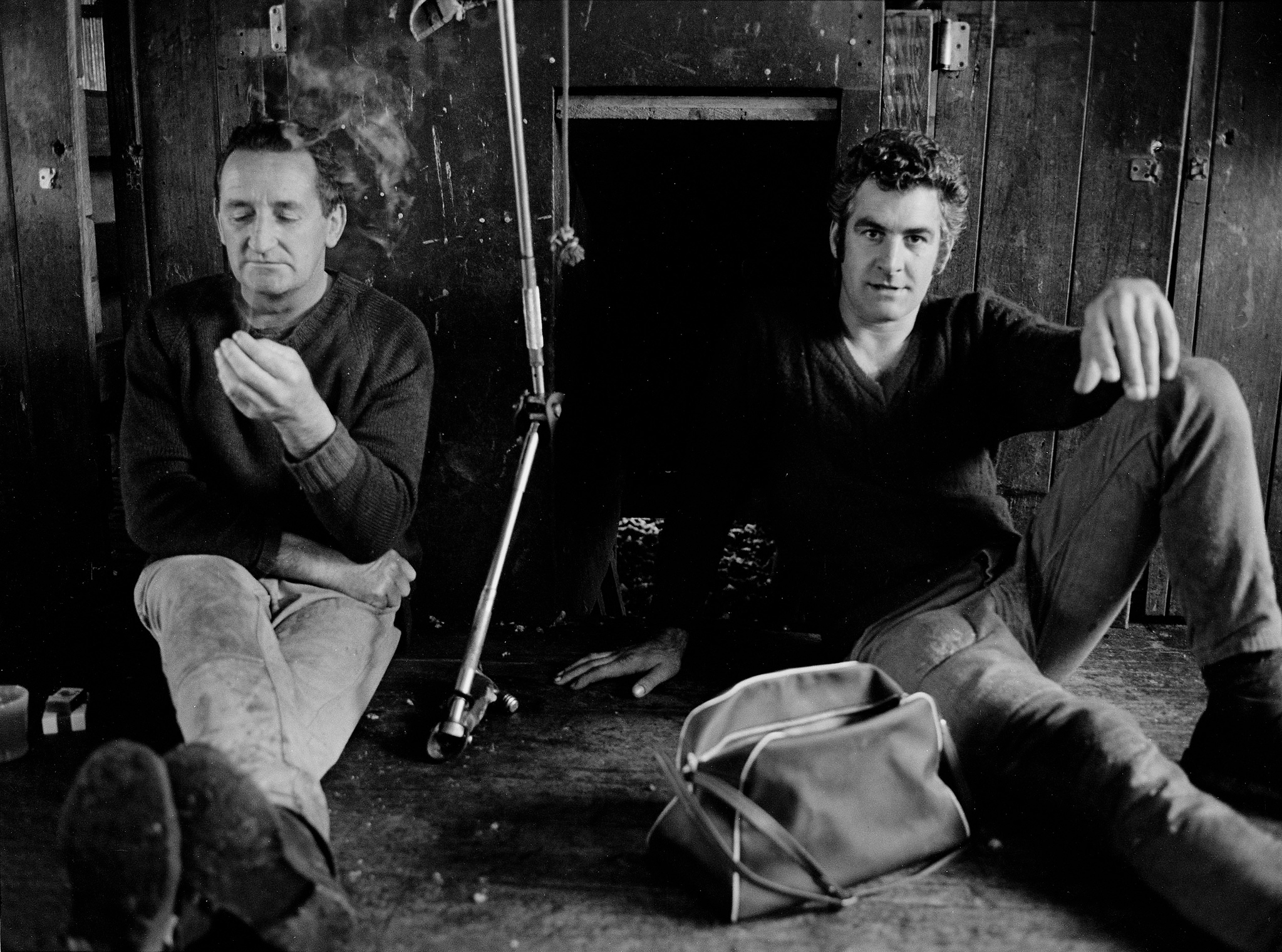

In ‘Mark of Time’ Chapman recounts his first encounter with a woolshed in 1976, a world of labour, character, and rugged beauty; the shed—its “timber floor and pens, well worn by lanolin, blood and sweat”—introduced a theme he would pursue for half a century, of rural communities bearing the “mark of time.” Seduced by the Australian countryside, he found in these regions a harsh yet “terrible beauty,” inhabited by people of resilience and authenticity. For a city-born photographer, documenting this world became an extended apprenticeship in understanding work, landscape, and endurance. The chapter highlights the sensory richness of these environments and how they offered a deepening connection to the people whose stories he recorded.

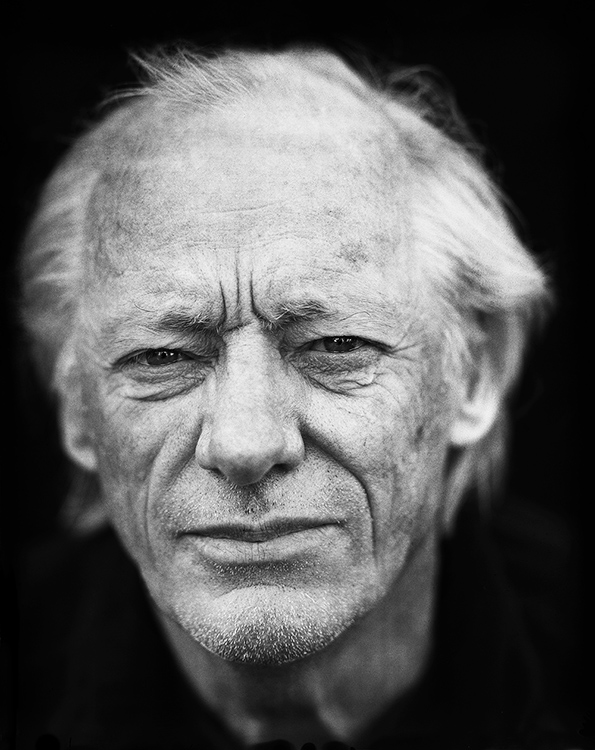

Chapman reflects on the challenge and mystery of portraiture in ‘Face to Face’. Though he has made many strong portraits—but admits to still more failures—he still seeks the elusive factor that brings a sitter truly to life. Unlike photographing inanimate subjects, working with people involves an unpredictable interplay and limited control. He recalls the tension of darkroom moments: hopes rising, then dashed as prints emerged, and often feeling like giving up. But he also experiences “magic”—a tilt of the head, a look in the eyes, a fleeting connection that transforms an image. Portraiture, he writes, is a lifelong pursuit of these treasured instants of human contact when the subject seems to look “right through you.”

Chapman’s evolving understanding of landscape includes his love of aerial photography. In ‘How you See It’ he remembers how as a child, the Australian landscape bored him and how only later did he learn to see pattern, shadow, season, and meaning, guided by mentor John Cato, who taught him to consider not just what a landscape is but what it represents. Landscape photography offers stillness and restoration, counter to his natural restlessness. His first flight in 1972 sparked a fascination with photographing from the air—balloons, helicopters, biplanes, jets—each offering new ways to see depth and form. Hot-air balloons, with their slow drift and unobstructed view, became his favourite platform. More recently, drones have allowed controlled low-altitude exploration. He stresses preparedness: aerial opportunities vanish quickly, and each flight yields “diamonds or dust.” These experiences sharpen his belief that landscape photography is as much mental discipline as visual practice.

In ‘Out There’ Chapman situates himself within the tradition of the documentary and street photographers to which he was exposed as a student in the 1970s: Cartier-Bresson, W. Eugene Smith, the FSA photographers, and others who shaped his understanding of “truth” and the “fly on the wall” approach. He remains committed to this ethos—recording life with minimal interference—and admires the masters who can quickly distil clarity from chaos. Yet the contemporary image world troubles him: billions of photographs, the explotation of gifted amateurs, digital manipulation, and AI, have blurred boundaries and devalued documentary photography. He acknowledges he, too, began as an enthusiast, and believes professionals cannot claim the medium exclusively. Still, he insists that standing up for truth in photojournalism is essential in an era of the “mad babble of mistruths.” Ultimately, he is driven by the hope that the best photograph is “the one I’m going to take tomorrow.”

A severe health crisis—from unexplained fatigue in the 1990s to a diagnosis of haemochromatosis, dangerously high iron levels, organ damage, and eventual liver failure is related in ‘Turning Point’. Facing mortality, he made the pivotal decision to stop commercial work and devote himself only to photography that “filled my creative soul,” even if it meant financial austerity. In 2011, two days from death, he received a liver transplant that gave him, in his words, “another 14 years of life which I had not been destined to have.” Supported by family and friends, he rebuilt his life with renewed clarity, continuing to refine rather than reinvent his practice.

The post-transplant years have been among his most productive, and he commits to working as long as he is able, and among his projects is his documentation of the Liver Transplant Unit at Austin Hospital for which his imagery provides publicity and raises funds.

Though most photographers loath being photographed, four pictures of Andrew himself in this book conjure his increasing confidence; first, despondently slumped against a fence with his mate, photographer Brian Pieper (now also a painter) in an image cancelled by obtruding strands of wire; in a self-portrait, seen from above, and submerged in a bath, his angst apparent in the hands clasped at his temples; handsomely saluting Brendan Hennessy, burnt-down roll-your-own between his fingers; and piercing through exhaustion and his stubbly, wrinkled and greying visage with a thousand-mile stare, in Tobias Titz’s concise shallow-focussed portrayal (a finalist in the inaugural Ballarat International Foto Biennale Martin Kantor Portrait Prize). These also signify Andrew’s gathering of strands around him into a community of photographers, Many Australian Photographers.

Andrew’s focus is emphatically humanist, born of an unshakable admiration of the ordinary person and their unique ‘everyday’ lives. That this luxuriously-produced book demonstrates the enduing effectiveness of his approach to that subject makes its lessons and advice relevant into the future for those dedicating themselves to this still-powerful medium.