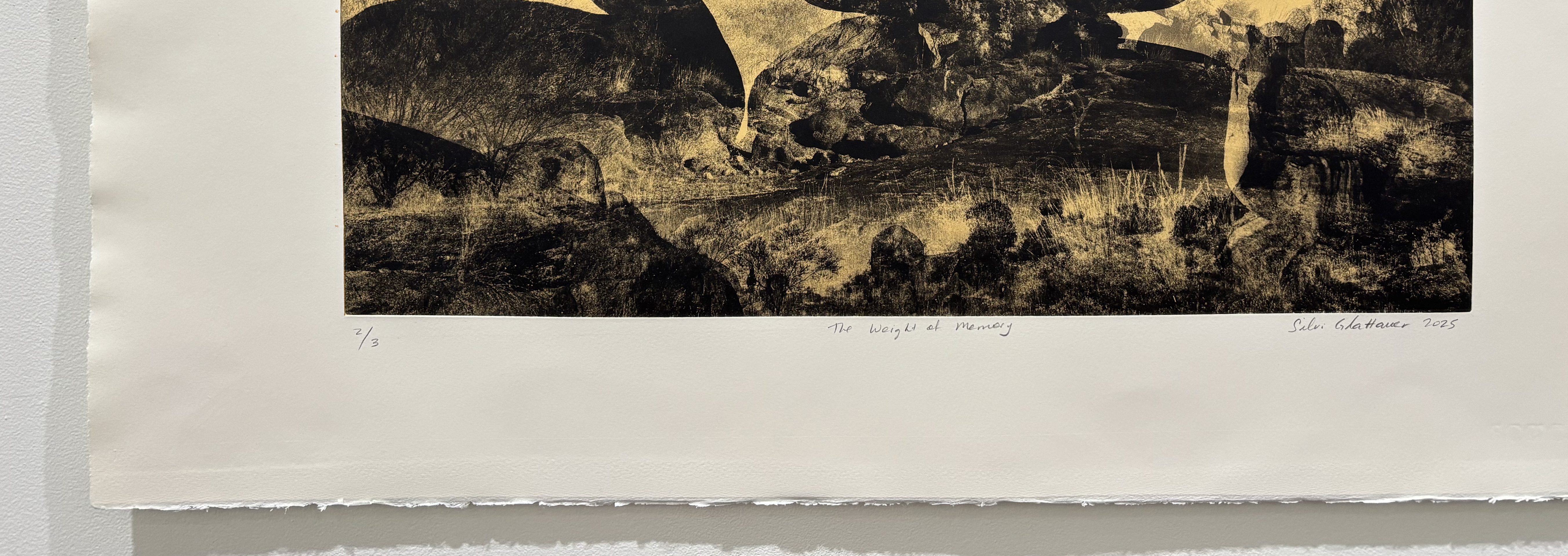

After a long and delightful lunch with my friend Jim McFarlane he suggested we go to see at PG Gallery in Fitzroy Re-Framing The Travel Shot by Silvi Glattauer whom he knew through the Many Australian Photographers (MAP) projects, and whose photogravure I had encountered at two of Castlemaine Art Museum’s biennial Experimental Print Prize exhibitions, of 2021 and 2023 at the latter of which she had passed on the awful news of the untimely death of Lloyd Godman, who only weeks before had invited me to Baldessin Press where Silvi, one of its founders, is studio manager.

After a long and delightful lunch with my friend Jim McFarlane he suggested we go to see at PG Gallery in Fitzroy Re-Framing The Travel Shot by Silvi Glattauer whom he knew through the Many Australian Photographers (MAP) projects, and whose photogravure I had encountered at two of Castlemaine Art Museum’s biennial Experimental Print Prize exhibitions, of 2021 and 2023 at the latter of which she had passed on the awful news of the untimely death of Lloyd Godman, who only weeks before had invited me to Baldessin Press where Silvi, one of its founders, is studio manager.

We jumped on a tram and made our way to PG Gallery at 227 Brunswick Street, Fitzroy where Silvi’s exhibition had opened the day before and is on until 14 June. It was deja-vu; I had often made my way to this address for teaching supplies when it was Melbourne Etching Supplies (MES) and had also housed the Print Guild (hence PG Gallery) since 1974 when that enterprise was established by Margie Burnet and Neil Wallace as a focus of printmaking in Melbourne.

Burnet had studied Art and Design at Prahran College and Wallace, who studied Metallurgy at RMIT, had become interested in printmaking whilst living in Toronto. Their enterprise supplied printmakers with fine quality materials, while the Print Guild promoted Australian printmakers by providing a space for them to exhibit their work. As the works of the artists required framing, conservation framing became another aspect of their business which employed Prahran alumnus Colin Abbott as traveling salesman for their line of custom aluminium mouldings.

It was entirely appropriate then that the exhibition should be in this space, because photogravure is, as the compound word indicates, imagery that is simultaneously photograph and intaglio engraving; it is a photograph rendered in ink.

But they are not made as are inkjet prints, or giclée prints are. That term was coined in the 1990s by printmaker Jack Duganne, who worked at Nash Editions (a pioneering digital print studio). He chose ‘giclée’ partly because it sounded elegant and French—a marketing euphemism to distinguish fine art prints from lowly-sounding “inkjet prints” — in effect they are screen prints. In colloquial French, une giclée means a male ejaculation, a slang usage that makes the term risqué or humorous to the French ear, just as the English “squirt” can in sexual contexts.

Photogravure is a respected and traditional craft that dates to the earliest photograph and Glattauer’s are no mere spritz, but made from inked plates pressed into the rag paper with an etching press, as is evident from the impression of the plate in the thick paper. She uses contemporary technology however, that dispenses with the copper plate and toxic acids traditionally used and which reduces the number of steps required in the original process which, it may be argued, was that used by Nicéphore Niépce to make the first photographs. He exposed plates coated with light-sensitive bitumen and etched them to make the plate itself the photographic image.

Glattauer uses a direct-to-plate photopolymer photogravure combining digital media and industrial flexographic photosensitive photopolymer printing plates. Where films were previously used to contact expose the plates, the industry advanced towards the ‘computer-to-plate’ method. Bypassing the film, the image can be printed directly on to the plate before exposure, while the water-soluble polymer structure of the plates allows for etching with nothing but water. Silvi has adapted advances in the offset printing industry and the ‘Direct to Plate’ to the artist studio, with the only disadvantage being the more rapid wearing of the softer photopolymer plate by the press. That limits the number of printings; hence the low edition numbers of the prints offered in this exhibition.

Littlefield.

In his essay printed for visitors to the exhibition and also available on the gallery website, Marcus O’Donnell describes Glattaeur’s “slow looking,” explaining that rather than capturing a singular moment, her images often emerge from multiple exposures and intricate printmaking processes, in resistance to the conventional notion the ‘fixed’ image. Each photograph as a point of departure, a dialogue between the history of her own work with the broader traditions of landscape representation. As Silvi explains it:

“I use my camera but not for documentation, but rather as means of reflection, and as a way to interpret imagined geographies, layered time, and quiet stories that linger beneath the surface. These are crafted images, made not to represent a single moment, but to evoke many. Each one is composed in sections that suggest the fragmented nature of perception and recollection.”

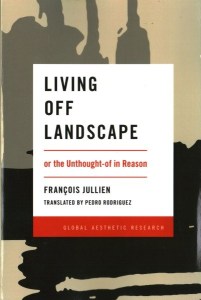

O’Donnell elucidates this layering and temporal elasticity in reference to French philosopher François Jullien who contends that Western viewers tend to fragment landscapes, focus solely on the visual, and maintain a subject/object divide. That distances us from a more immersive understanding of place. Glattauer, O’Donnell explains, counters these tendencies, and the resultant partial, static views, by layering images from repeated visits to sites. Furthermore, her process itself represents an accumulation over time—multiple decisions made about exposure, the plate making, inking, and pressure—so that resulting in images that feel alive with both history and possibility.

He points out that in her latest series, Glattauer experiments with in-camera multiple exposures, challenging herself to create images that allow random elements to coalesce organically: taking her “cue from the Italian Futurists, she explores photodynamism where the layers are more deliberately set to dance with, against and around one another”, she generates compositions where layers of landscape intersect, overlap, or even clash, producing a sense of movement and tension:

“This act of looking is more than one of visual capture, it is one born of movement and gesture, that involves her whole body. We can feel the swing of her arm and the pivot of her body in the composition of these images. Because Glattauer has photographed many of these sites before, the new exposures offer fresh ways to “reframe the travel shot,” as she puts it. By physically moving—swinging her arm, pivoting her body—she transforms photography into a performative act, where gesture and perspective become integral to perception.”

Drawing on anthropologist Tim Ingold’s idea that perception is an act of world-making, O’Donnell suggests that Glattauer’s work exemplifies “making visible rather than reproducing the visible.” These are travel photographs in one sense, but ‘re-framed’ as Silvi worked,

“teaching and leading photo tours I have been going back to the same places over and over, particularly to Spain and Argentina and Morocco. So, every time I travel, I give myself a challenge to do something different. To photograph in a completely different way to what I did before. So, for instance, the first time I went to the high plains of Argentina I was so struck by the hugeness and the colours, that I did a show which focused on really big colour prints, a metre and a half by two metres. The original colours all felt like beautiful watercolours. And so when I went back, I think the second or third time, I challenged myself to only work small and in black and white.”

As a print medium, photogravure lends itself to the creation of publications; Peter Henry Emerson’s 1888 Pictures of East Anglian Life is “illustrated with Thirty-Two Photogravures” for example, and Alfred Stieglitz in his Camera Work featured the photogravures of Alvin Langdon Coburn. Glattauer’s book invites you to accompany her on the journeys

Every photograph may be a travel shot, if life is considered to be a journey, but the category is universally recognised; pictures made on people’s tourist trips are among the majority of photographs on social media, there only rarely to simply inform relatives about where in the world we are, they are boastful, motivated by a desire to arouse jealousy amongst one’s acquaintances and work colleagues. According to a 2022 report by Statista, travel was among the top 5 most popular content categories on Instagram, alongside fashion, food, fitness, and lifestyle. While many a photography student may have dreamed of making a living in travel magazines and jetting around the world, such images, so commonplace, are a debased form, and it is little wonder that Glattaeur’s artist book protests It’s not a travel shot, it’s not a snap shot!

But how do we define this genre, of pictures made on our travels?

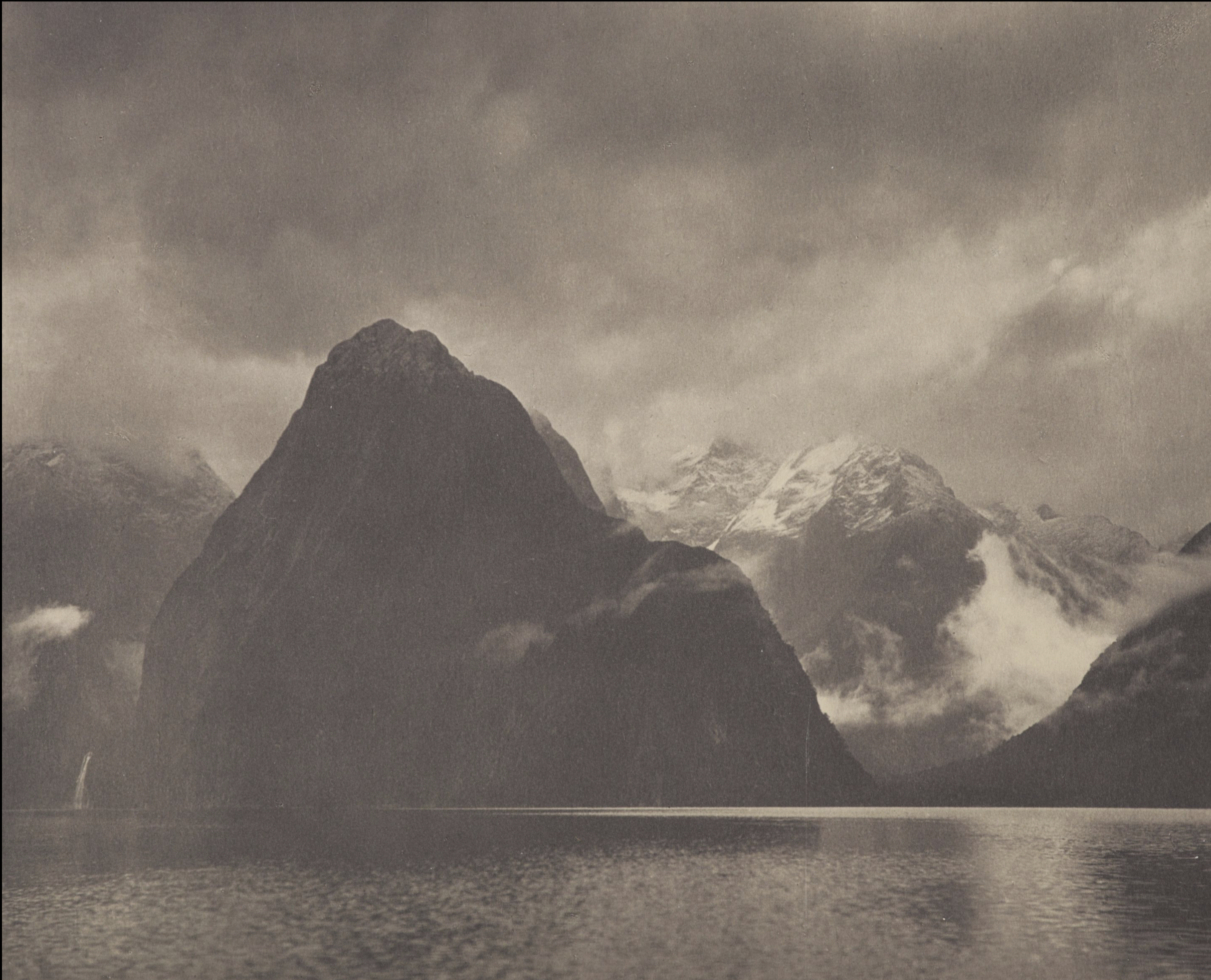

Let’s traverse the Tasman Sea and in New Zealand look back to the 1920s and to Harry Moult, about whom photography historian David J Langman, former director of the New Zealand Centre for Photography 2000–08 and, from 2015, the Galerie Langman, has recently alerted me.

Moult’s obituary in the Wanganui Chronicle after his death in Wellington in March 1948 notes his arrival in New Zealand with his parents on the Arethusa in 1878 from England, where he was born at Stockport, Cheshire. Educated at Wanganui Collegiate School he became an engineer, and after serving his apprenticeship he went to sea for a short time before seeing more potential in electrical engineering.

Moult went for further experience in England and in May 1901 was there studying for an examination, having been apprenticed for eight months by the General Electric Company in his parent’s home town Salford, Manchester, and then worked for the De Ferranti Company . On his return to New Zealand he was contracted for the overhead wiring and assembly of the electric trams in Christchurch. In 1906 after another short trip to London, by 1919 he had a business in Wellington as a lift specialist, and in 1923 formed his own company which installed the Durie Hill lift at Wanganui. He made at least five return trips to England between 1906 and 1931.

Evidence of his ingenuity in our field, and as a hint of his future work in photography The Wanganui Herald of 20 April 1900 reported on his construction of a “Rontgen ray apparatus” (an X-ray machine) and display of his first image made with it, of coins in a purse. His innovations in photographic technologies continued; the venerable German abstracts journal Chemisches Zentralblatt reports in 1931 on his:

“Production of multicolour photographic positive images. The three partial negatives are copied onto the same side of the image carrier, one above the other. After development, each image is treated with a sulfo-cyanide copper mordant, and the mordant image is coloured with a basic dye (methylene blue, auramine, or fuchsin). A celluloid coat is applied between the individual emulsions.”

The obituary does not record that he took up photography in 1920 with success within the Wellington Photographic Society. After 1924 he and the small group he formed, the Wellington Camera Circle, concentrated solely on pictorialist photography. New Zealand was no laggard in adopting this photographic style; locals were already practicing it only four years after the Linked Ring Brotherhood had been formed in 1896 in Britain.

During another business trip to the UK in the late 1920s Moult commissioned the printing of his best negatives by the carbon process, in which tissue coated with a layer of gelatin mixed with a pigment, carbon black, is sensitised with potassium dichromate, dried, then exposed to strong ultraviolet light through a photographic negative. That hardens the gelatin most in the clear (shadow) areas, and warm water dissolves the unhardened gelatin. The pigment image is physically transferred to a final support surface, either directly or indirectly. Carbro (carbon-bromide) printing, invented in the early 1900s selectively hardened the gelatin by contact with a conventional silver bromide paper print, rather than exposure to light. Colour, through the wide choice of pigments, was not restricted to carbon black.

These prints he exhibited for a week upon his return to Wellington at the New Zealand Academy of Fine Arts (precursor to New Zealand’s first National Gallery, where his imagery may now be seen online) in September 1930, the show being opened by amateur photographer the Governor-General, Lord Bledisloe who joked that he might swap sport shooting for an opportunity to bag ‘some of your scenic spots’.

Moult, in capturing what would be thought now to be a less ‘Instagrammable’ London meteorological event, is following a pictorialist interest in atmospheric effects; Alfred Stieglitz’s Spring Showers, The Coach is a precedent that appeared in Camera Notes, Vol 5, No 3, 1902. Senior Lecturer in History at the University of Auckland Dr Felicity Barnes (see her New Zealand’s London: A Colony and Its Metropolis of 2013) brings to attention Moult’s placement in his show of pictorialist representations of the British metropolis beside his imagery of sublime New Zealand landscape and familiar British scenes and everyday London street life.

Wellington’s Evening Post reported the exhibition: ‘Most people are familiar with pictures of London, and to those especially who have visited the Homeland, the various typical scenes are a source of keen delight.’

The arrival of photography in the mid-nineteenth century enabled an image-driven colonisation of New Zealand which Barnes identifies as an ‘extractive industry’ for consumption in a mass market for visual culture. Moreover that special category of travel photography, that which records the discovery of new lands beside or just behind the explorer, is a declaration of settler territorialisation. Is that not still part of our drive to record our own ‘discoveries’?

In the later instance of Moult’s exhibition, the display of images of countries that are global antipodes side-by-side is a ‘re-colonisation,’ in that Moult represents New Zealand’s landscape as a ‘hinterland’ of Great Britain in a reciprocal relation rather than ‘poles apart’. England to which he so frequently returned as his place of birth, his homeland, he represents in the guise of the Home Country, now extended, relocated or indeed co-located, in his transformations of New Zealand places with ‘Englishness’. But the English rural idyll was not easy to recreate in the colonial setting. Barnes quotes the advice of photographic supplier Sharland and Co. in its Sharland’s New Zealand Photographer;

“Farmhouses in the dominion suffer from the fault of being too modern. We have no abbey farms with gnarled trees and the stone homestead hoary with age and weight of ivy around its walls. … therefore in farm landscape picture making there is ample scope for careful reflection in order to give the correct emotional value to the photograph.”

The endless repetition of tourist photographs enabled Photo Tourism, a research project started twenty years ago by University of Washington graduate student Noah Snavely (now Professor) who realised that a 3D rendering of a monument such as the Colosseum could be produced from uploads—thousands, taken from almost every angle and distance— to Flickr. Microsoft adapted the technology for the now defunct Photosynth that enabled a fly-through of such places entirely from tourist photographs. The Photosynth technology was eventually integrated into Bing Maps, allowing users to explore 3-D models of locations and environments. While Google Street View developed use of its own panoramic photography, both technologies shared the core concept of creating immersive, interactive maps.

How then is a ‘re-framing’ of the tourist of travel photograph to be achieved? Harry Moult and other pictorialists competed with the advent of the Kodak and less technical photography through his artistic intentions aided by the use of technologies aligned to painting and printmaking which enabled the removal of ‘unsightly’ elements from the scene and the application of atmospheric effects, like clouds, mist and fog, and radical manipulation of light and shade.

We see in Silvi Glattauer’s work a still more emphatic and lyrical layering that implies time and movement in space and demands interpretation by the viewer.

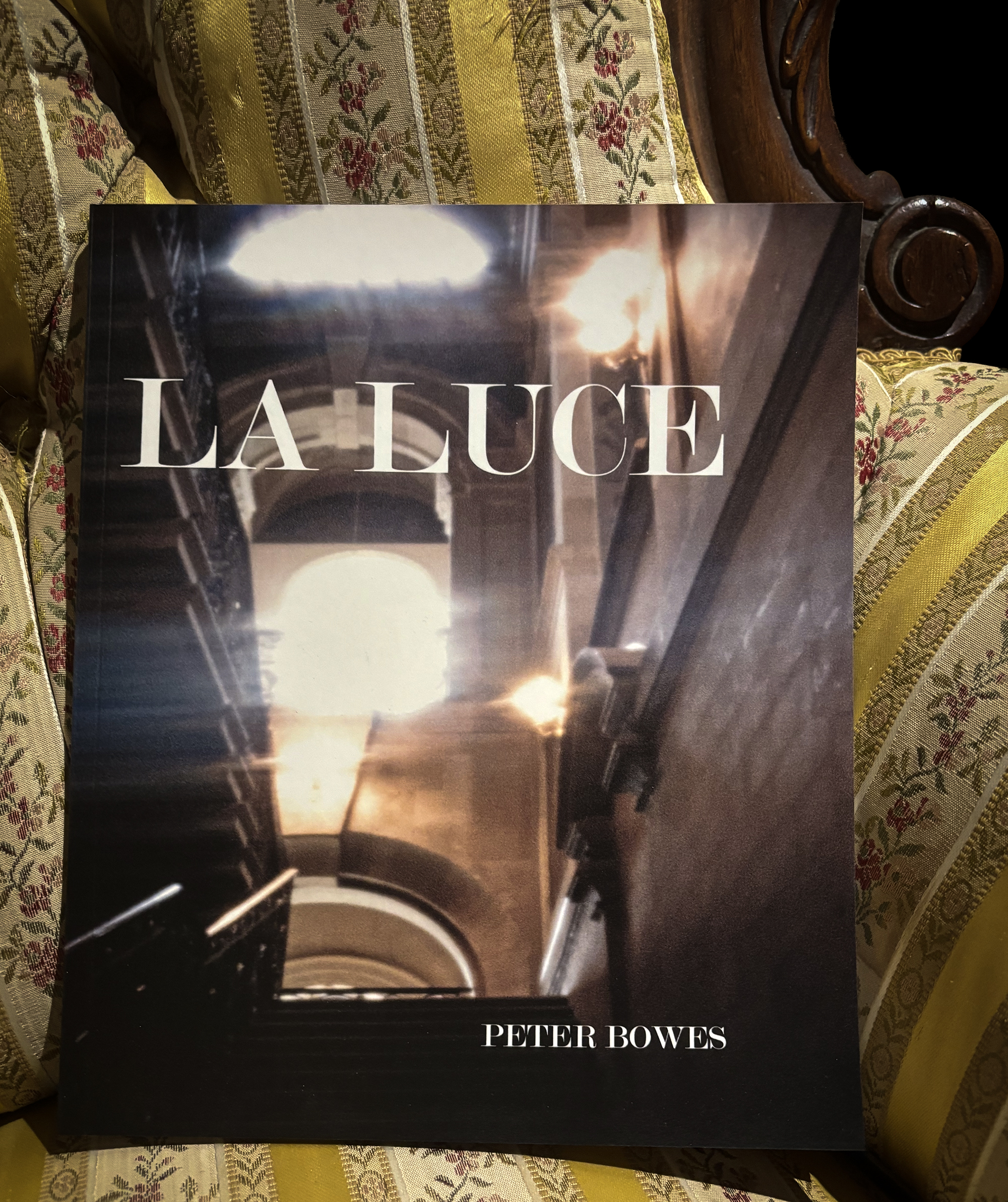

Let me turn to one more strategy that may ameliorate, or refine, the travel photograph in another book. Peter Bowes, edging into his seventies in 2022, made his first trip overseas and took with him a determination to capture the atmosphere of a beloved novel E. M. Forster’s A Room with a View, which charges vignettes such as this with British attitudes and psychology:

Let me turn to one more strategy that may ameliorate, or refine, the travel photograph in another book. Peter Bowes, edging into his seventies in 2022, made his first trip overseas and took with him a determination to capture the atmosphere of a beloved novel E. M. Forster’s A Room with a View, which charges vignettes such as this with British attitudes and psychology:

“It was pleasant to wake up in Florence, to open the eyes upon a bright bare room, with a floor of red tiles which look clean though they are not; with a painted ceiling whereon pink griffins and blue amorini sport in a forest of yellow violins and bassoons. It was pleasant, too, to fling wide the windows, pinching the fingers in unfamiliar fastenings, to lean out into sunshine with beautiful hills and trees and marble churches opposite, and, close below, Arno, gurgling against the embankment of the road.”

or of intrigue:

“She went up to the dripping window and strained her eyes into the darkness. She could not think what she would have done.”

…of passion:

“He carried her to the window, so that she, too, saw all the view. They sank upon their knees invisible from the road, they hoped, and began to whisper one another’s names. Ah! it was worth while; it was the great joy that they had expected, and countless little joys of which they had never dreamt. They were silent.”

…and memory:

“She recalled the free, pleasant life of her home, where she was allowed to do everything, and where nothing ever happened to her. The road up through the pine-woods, the clean drawing-room, the view over the Sussex Weald – all hung before her bright and distinct, but pathetic as the pictures in a gallery to which, after much experience, a traveller returns.”

Peter has followed a career as a builder and a real estate photographer since leaving Prahran College. In his love for this medium has crafted elegantly simple wooden pinhole cameras for large-format sheet-film. He describes how he adapted from his experience to produce these evocative images:

Let Forster have the last word:

“The Loggia showed as the triple entrance of a cave, wherein dwelt many a deity, shadowy, but immortal, looking forth upon the arrivals and departures of mankind. It was the hour of unreality – the hour, that is, when unfamiliar things are real.”

James I particularly enjoyed your piece about Silvi Glattauer‘s current exhibition. It sent me down a rabbit hole on the photogravure technique.

best

Sharon.

LikeLike

Thank you Sharon. It’s a modest little show, but the work on the imagery is huge and arduous, and such prints are worth seeing in person if you can. Silvi runs workshops on photogravure, including online.

All the best, James

LikeLiked by 1 person

My goodness! I can see this blog is a moving feast of essays on art, practice and technology, past and present. So beautifully written, so much to learn here. Thank you James.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I love this post. The photographs especially by Silvi Glatteaur are really inspiring and her comment – “I use my camera but not for documentation, but rather as means of reflection, and as a way to interpret imagined geographies, layered time, and quiet stories that linger beneath the surface. These are crafted images, made not to represent a single moment, but to evoke many. Each one is composed in sections that suggest the fragmented nature of perception and recollection.” – resonates. Thank you for sharing 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

As changing circumstances have made overseas travel more and more difficult for me, I have to admit to expressing jealousy when viewing some of my family and friends travel shots – especially when they visit places I went to long ago and my memories come rushing at me or when they travel to places I’ve never been to and would love to visit. So I very much related to your comment about social media travel images being posted because their authors are “motivated by a desire to arouse jealousy”.

LikeLike