It is in the nature of the medium that the photographer be ever-ready for chance happenings, but sometimes such events occur beyond the frame.

It is in the nature of the medium that the photographer be ever-ready for chance happenings, but sometimes such events occur beyond the frame.

While he was exhibiting his Rohingya Edge of Hope exhibition at Gallery Niepce in Yotsuya, Tokyo in February 2024, Jim McFarlane had a surprising and fortuitous encounter:

“I was talking to some students when Ishikawa arrived, I didn’t know who he was. He looked around quickly at the photos and then took a seat. I acknowledged his presence and continued talking to the students for a while longer. He just sat there patiently and I thought maybe he was interested in my conversation with the students. After the students disbanded he approached me and a conversation ensued. I can’t quite remember how it started, maybe he asked where I was from and I then would have told him that I was half Japanese, as I normally do when I’m in Japan.

“It turned out that he is a friend of the gallery owner Takehiko Nakafuji (a past student of Daido Moriyama) and I remember that Takehiko told me that Eugene Smith’s assistant was a friend of the gallery. We chatted on for a good while, his English is quite okay and he proceeded to visit each day. He told me about the long form projects he was doing in India about the Hydra and the River Ganges.

“It’s funny that the pictures on exhibition were never discussed. That is something that I noticed when exhibiting work in Japan; that is, if the work is up to scratch, you are then worthy of being spoken to, but still, the work is not talked about. This does not just pertain to Ishikawa but to other noted photographers as they pass through.

“After I returned to Australia in mid year, Ishikawa went to London to see if he could interest a publisher to take on his projects. I alerted my colleague Anthony [Dawton], who luckily lived near Ishikawa’s hotel and took Ishikawa under his wing. Anthony did what he could for him and visited him each day.

“Later in the year I was back in Tokyo for the Gaza exhibition in another gallery called Place M. It’s the oldest photo gallery in Tokyo, run by Masato Seto who founded it with Daido Moriyama. Again Ishikawa visited almost every day and he took me to the famous photographer’s bar in Golden Gai in Shinjuku, a tiny intimate place attended mostly by photographers. After too many drinks we struggled down the very steep narrow staircase onto the laneway below. These were the very steps that a drunk Masahisa Fukase fell down, resulting in his tragic slow and painful demise. His pictures of crows are unforgettable.”

Wind back to September or early October, 1971 to another chance encounter; by 21-year-old Ishikawa with W. Eugene Smith on the streets of Harajuku, leading to an unexpected role as an assistant to Smith and his wife Aileen Mioko Smith during their documentation of the Minamata disease in Japan.

This is the subject of the book that Takeshi Ishikawa 石川武志 gave to Jim.

Ishikawa’s narrative offers remarkable, sometimes surprising insights into Smith’s working methods, darkroom techniques, and his personal approach to documentary photography in challenging conditions.

After spontaneously offering assistance, Ishikawa was immediately recruited for their work, initially translating Japanese documents about Minamata disease and the kanji used on leaflets by those protesting “The Sea of Death:”

“The language used in these flyers were typical for letters of protest, which meant that they used a lot of difficult Chinese characters. Aileen had grown up in Japan until about the fifth grade then moved to the United States, so she could no longer comprehend most of these Chinese characters. I would reword these sentences written in difficult Japanese into an easier conversational mode, and Aileen would then translate that into English for Eugene.”

Ishikawa assisted with the couple’s move to Minamata, and helping with film development:

“I assisted however I could but often was just watching Eugene go through the developing process. I couldn’t contain the surge of elation I felt knowing that I was watching Eugene Smith develop film in front of my own eyes. On top of all this, the wash basin being used to wash the film was the one that Eugene was carrying when I met him on the street the other day. (He was on his way back from going shopping.)”

What began as casual assistance quickly evolved into regular darkroom work that often extended into the early morning hours, due to the demanding nature of Smith’s documentary process and the new assistant’s growing involvement in the project. Smith said that he really wanted to make the contact sheet:

“Being a photographer myself, I understood his feeling wholeheartedly. Meanwhile, the reality he faced was that he’d gone to Minamata just the other day right in the middle of his hectic photography exhibition [Let Truth be the Prejudice] in Tokyo, and he didn’t have a darkroom yet. “Do you have a darkroom at your place?” he asked me. I told him, “I don’t have one but I close all the windows in the middle of the night and make prints.” His response was that that’ll do and that he really wanted to make the contact sheets. >

“So I brought back to my little apartment the film that the one-and-only Eugene Smith had taken, and made contact sheets at night…never did I expect to take Eugene Smith’s films there to make contact sheets! There were so many unexpected things happening already at this point that I didn’t know what else to expect anymore. The contact sheets showed the Chisso plant, mullet fishing, and Minamata Disease patients. These were the first Minamata photos I saw that were taken by Eugene Smith.”

Eugene Smith’s determination to continue his work led to creating improvised darkrooms in challenging spaces. The first darkroom was established in a tiny bathroom in the Harajuku Central Apartments:

“We took the western-style toilet seat and used it as a table for the enlarger. Then we put blocks on the four corners of the bath tub, placed a duckboard on top for the developer and fixer trays. We of course used the bathtub for washing. What was difficult was this table for the enlarger. We had to be able to keep using the toilet for its actual use, so next to where we put the enlarger, we used a fretsaw to cut out a U-shaped hole the size of the circumference of human torso. To prevent any warping a very thick board was used , so cutting a hole with a fretsaw was difficult. As for the enlarger, Eugene set it up carefully using a level. I was aghast that he was taking this much care for a mere darkroom, but told myself, “I’m witnessing Eugene Smith’s darkroom-making process and this much care makes absolute logical sense, because it is the legendary Eugene Smith after all!” At the same time, though, I was staring at this process feeling apprehensive as to what more was to come.

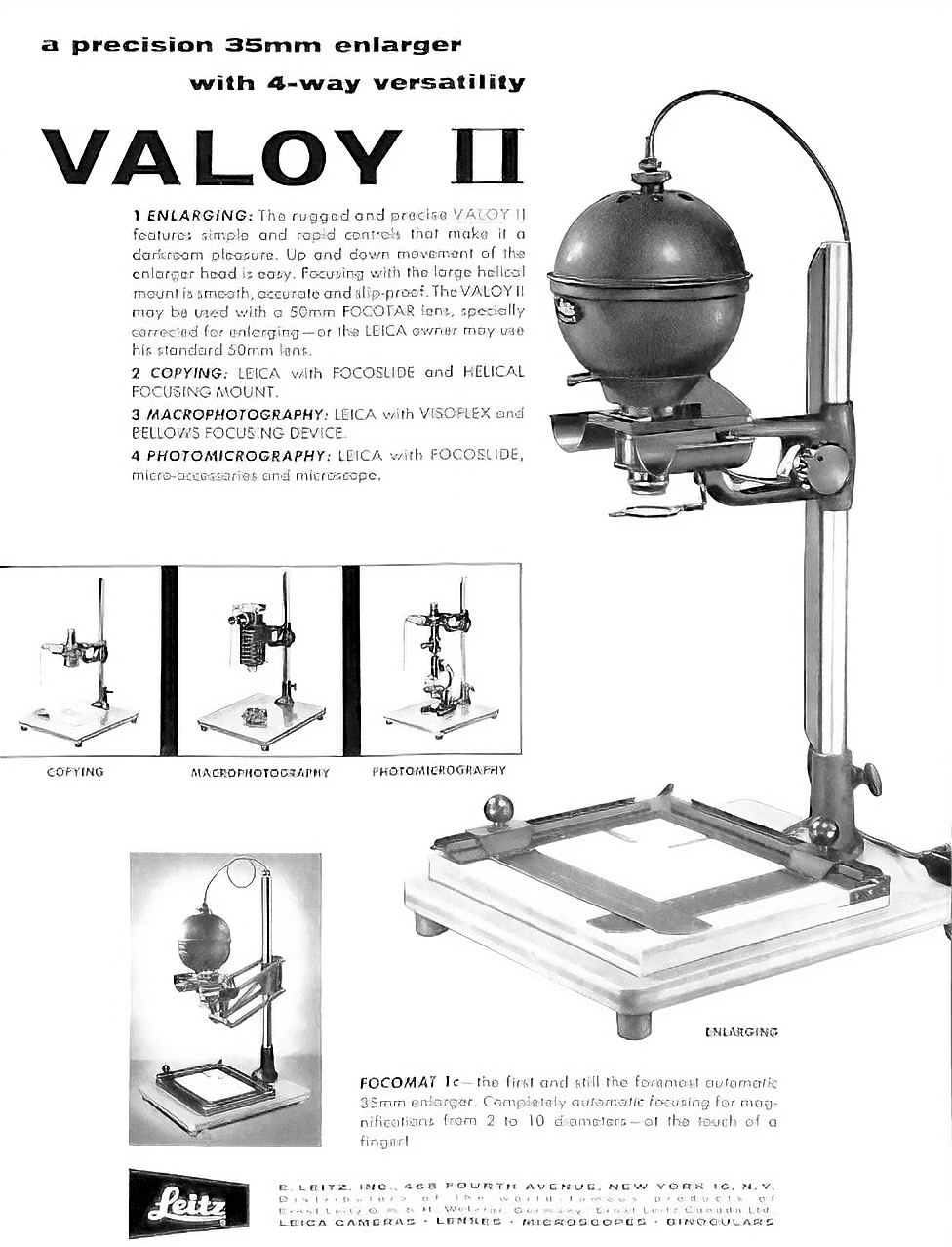

The enlarger was a Leitz Valoy with a Summicron lens that Mr. Jun Morinaga, who was Eugene’s assistant in Japan in 1961, got for him. In this ad hoc darkroom, all we could print were proof prints and contact sheets on 10 x 12 inch and 11 x 14 inch paper so we could look at the contact sheets and make the basic prints. Eugene was impatient, and immediately started to develop films from the photoshoot in Minamata the other day and to make contact sheets. He stared at the contact sheet and marked the photos he chose with a red chinagraph pencil. He taught me how to make 5 x 7 inch proof prints, and as they were made, the Chisso plant, mullet fishing, and Minamata Disease patients locked inside those contact sheets came to life, one by one: “Wow, I’m now literally touching Eugene Smith’s real photographs… I’m a part of this process…” Those thoughts came over me and I really couldn’t contain the excitement any more.”

As the project progressed, the Smiths established a more permanent base in Minamata in an abandoned house. The rotten wooden floor had to be completely replaced. Despite its deteriorated condition, they created a proper darkroom by converting two adjoining rooms, replacing paper sliding doors with plywood, and using hanging wool blankets as light barriers.

To preserve image sharpness floor vibrations had to be prevented from affecting the enlarger, so rather than attaching support columns to the floor, Eugene secured them diagonally to wall joists.

Perhaps the most revealing insight into Smith’s process was his scientific approach to lighting that acknowledged the psychological aspects of visual perception alongside technical photographic considerations. Two red safelights were positioned; one on the enlarger table, and another above the tray table, and connected to the foot-switch so that stepping on the switch turned on the enlarger light for exposures but turned off darkroom lights, making it easier to see the projected negative during exposure.

“Eugene was also particular about something else: his print inspection lamp. He carefully decided where on the wall to attach the lightbulb in order to avoid having it reflect on the fixer. He then took out the Sekonic light meter that he uses, and began measuring the amount of light falling on the exact position where the fixer tray will be set. I’d never thought to care about how many watts the lightbulb in the darkroom was, but Eugene said he decided on the amount of light needed for looking at his own photographs by using the light meter. What that means is that if he decided that the most appropriate amount of light for him to look at his own photographs was 125 according to the light meter, then he must set the darkroom light at 125, his editing workspace at 125, and the venue for his photography exhibitions, must also be lit at 125. Thus Eugene measured the amount of light exactly where he lifted the print out of the fixer, turned the light on, and checked his prints for the first time. Human eyes automatically adjust for light. This means that the standard by which human beings measure the lightness or darkness of the printed image is obscure, and so he was using the light meter to make more objective decisions.

“Eugene was also particular about something else: his print inspection lamp. He carefully decided where on the wall to attach the lightbulb in order to avoid having it reflect on the fixer. He then took out the Sekonic light meter that he uses, and began measuring the amount of light falling on the exact position where the fixer tray will be set. I’d never thought to care about how many watts the lightbulb in the darkroom was, but Eugene said he decided on the amount of light needed for looking at his own photographs by using the light meter. What that means is that if he decided that the most appropriate amount of light for him to look at his own photographs was 125 according to the light meter, then he must set the darkroom light at 125, his editing workspace at 125, and the venue for his photography exhibitions, must also be lit at 125. Thus Eugene measured the amount of light exactly where he lifted the print out of the fixer, turned the light on, and checked his prints for the first time. Human eyes automatically adjust for light. This means that the standard by which human beings measure the lightness or darkness of the printed image is obscure, and so he was using the light meter to make more objective decisions.

“He brought the Leitz Valoy enlarger that he was using in Tokyo. This was what Jun Morinaga got for him way back when. The lens was a Summicron 50mm/f3.5. Eugene did not hold back on his criticism of Japanese enlargers. ‘With Japanese enlargers, once you touch it goes out of focus. Japan makes world-renowned high-quality cameras, and it’s a mystery why all the Japanese enlargers are awful.’ He also added, ‘With (the American) Omega, it turns out too sharp and grainy. I don’t like the negative carrier, either. The heat makes the film curl if you’re doing the long-time exposure for burns.’

Ishikawa notes:

“This is just my opinion, but, in Japan, I think many people have particular preferences for cameras, but when it comes to prints and photographs themselves, there are fewer people who have thoroughly particular preferences. Eugene would say, ‘It’s not only the enlargers, but with portfolio cases, too. There are no decent ones made in Japan.’ Indeed, when I am talking with photographers, we often end up talking about cameras but hardly ever show each other our prints. I wonder if this is a distinct difference in photography culture here compared to elsewhere.”

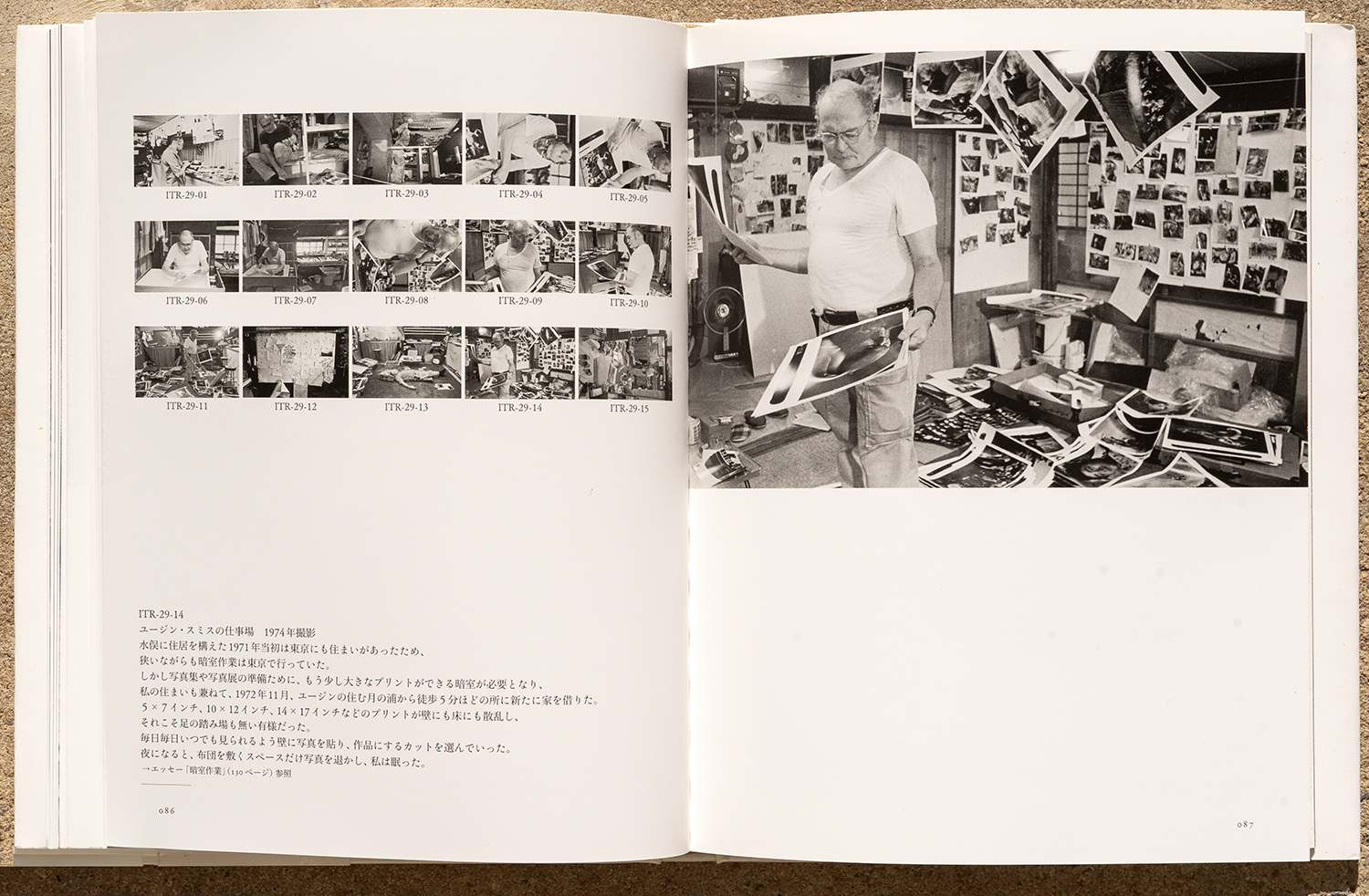

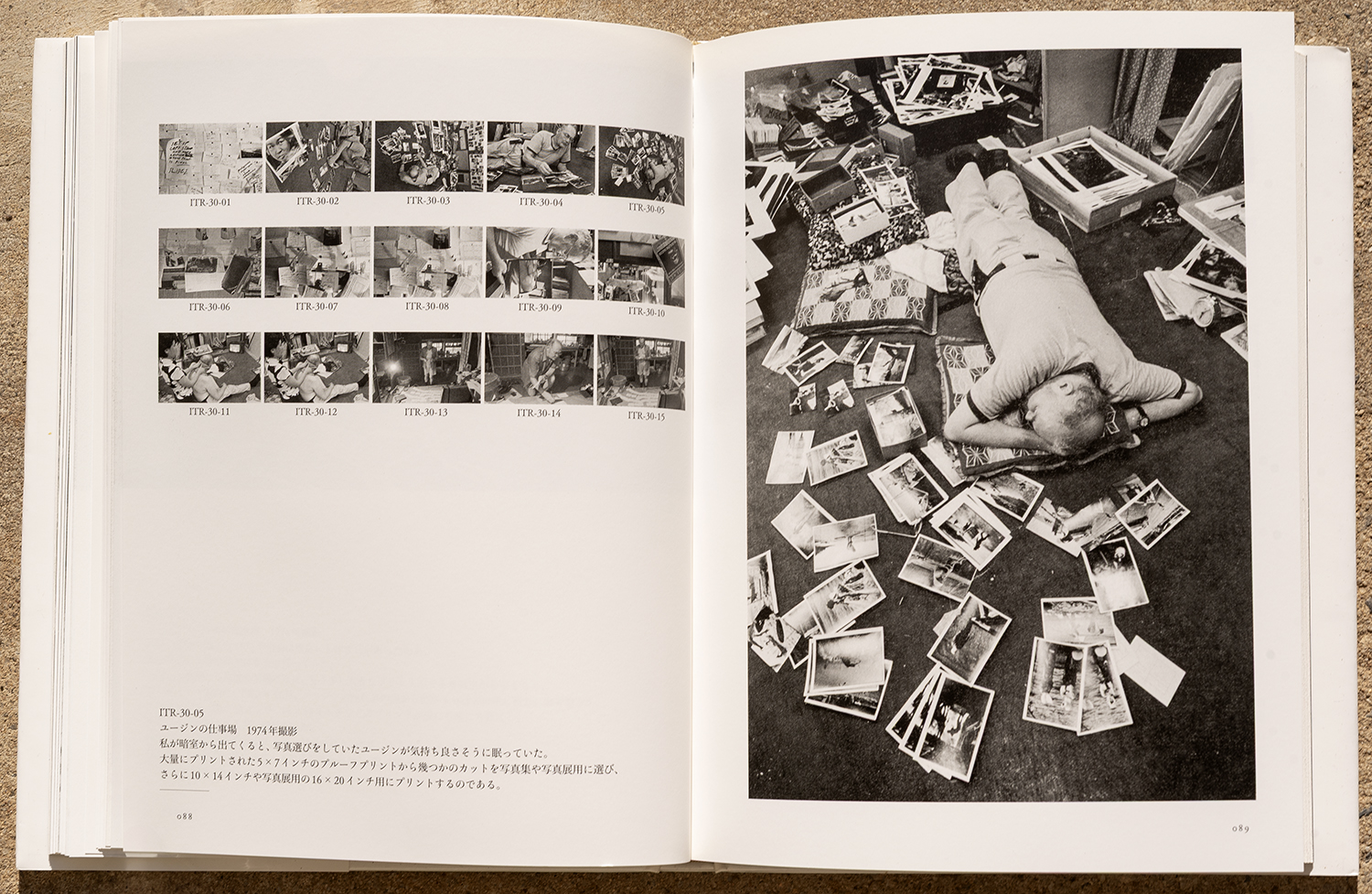

Ishikawa records that Smith worked with specific materials chosen through careful testing. He used Kodak Tri-X film under-rated at ISO 320 (underexposing the nominal ISO 400 film), and developed it in Kodak D76 developer diluted 2:1 with water to produce softer negatives with reduced contrast and the nominally 8-minute development time was adjusted according to shooting conditions and the condition of the developer. He printed on Mitsubishi GEKKO NR semi-gloss baryta paper (typically grade 2), a choice made after testing various options available in Japan—the semi-gloss surface kept blacks saturated without excessive glare, while the grade 2 contrast complimented the film development. He applied a disciplined redundancy in printing, as he created multiple proof prints (minimum three to five) even for preliminary selection. Each print served a specific purpose: one for display and evaluation, another for layout experiments and editing, and at least one for archival purposes, a systematic approach that meant that stages of the creative process were preserved while allowing freedom to explore different presentation options.

One day, Ishikawa asked Eugene, ‘Why are multiple photographs that look very similar being pinned to the walls?’ and recorded Eugene’s response:

“I look at the same photographs for at least a few months before I decide which one is good. I need to look at hundreds and hundreds of photographs all the time, every single day, to be able to make a careful selection. For a photograph to be in a photo-book, it must be good enough to withstand people looking at it for years to come. Even if I thought it was good right after I took it, it may not be good after some time. That’s why I need to make proof prints and keep them where it would catch my eye for several months, and in that time I make selections, pick ones that would make a pair on the left and right sides of the two pages, and think of layouts that would turn into the story. At the same time, I also always make sure which photographs I have enough of in this project, and which ones I don’t.”

Ishikawa goes on to write:

“There were exceptions. One time, Eugene was having a hard time choosing a photograph out of four or five similar ones of a Minamata Disease patient. I just happened to be nearby and he asked me, “Which one would you choose?” so I pointed at one and said, “If I were you, I’d choose this one.” On hearing that, he didn’t even think twice and declared, “All right, this is it, then.” I thought in my heart, “Please don’t ask the assistant for your opinion, world-famous Eugene Smith,” but that incident made me wonder for some time whether he ever ended up not knowing what he really wants after looking at it too much, or if he thought that other people’s first impressions were important.”

The first hand account provided by his assistant is valuable for its rare, conscientiously recorded insights into the working methods of one of photography’s most committed documentarians, his unyielding perfectionism and willingness to work in difficult conditions for the sake of an important story. Eugene Smith’s meticulous control of the entire chain of production and presentation, darkroom construction, precise calibration of lighting conditions, and systematic workflow all contributed to his creating stark images that drew world attention to the avoidable tragedy of the Chisso company’s poisoning and crippling of generations of children by releasing organic mercury into the sea from which Minimata people obtained their staple food. Ishikawa’s narrative conveys his deep respect and admiration for the legendary Eugene Smith, whose dedication to his craft left a lasting and transformative impression.

“Eugene’s printing is legendary; I’ve heard people say that he printed from one negative for several days straight using 100 sheets of paper. However, as far as my experience with him goes in Minamata, with the 14 by 17 inch and 16 by 20 inch prints for exhibitions and publications, we used maybe 10 to 15 sheets of paper to get two or three good prints from one negative. Even with backlit and difficult negatives, he would give a passing grade to a print within 20 or so tries. What I mean here by a “passing grade” is that Eugene gave his seal of approval to a print as something that had good enough quality to be used for an exhibition or a publication, or to be sold to a gallery or collector.

“For prints that received his seal of approval, sometimes he finished them up right there and then using potassium ferricyanide, while other times he lightly fixed and washed them, and took time bleaching them at a later date. Bleaching takes place at the fixer stage for lightening parts that are too dark, further whitening the white parts such as teeth and eyes, giving a glossier look to lips, and otherwise giving the photograph life. Because it takes about 10 to 20 minutes per print, you end up working in individual soft hypo (sodium thiosulfate) baths for each print. For the fine details, we use spotting brushes, paint brushes, or cotton swabs. For bigger areas such as the sky or the sea, we usually use absorbent cotton, but if that was not available, then we used sanitary napkins or anything we could get.

“Finally, at this point, we dried the prints we laboured over. This was done on large mesh screens, and air-drying the prints while being careful not to let them curl up. There were problems, however. During the summer, scarab beetles, moths, and other insects came flying in, and their carcasses and excrements could drop on the prints. And on a windy day in the winter, dust would fall onto the prints directly from the roof. Eugene could not put up with that, and so he asked Mr. Mizoguchi, the landlord, who was a retired carpenter, to fix the ceiling.

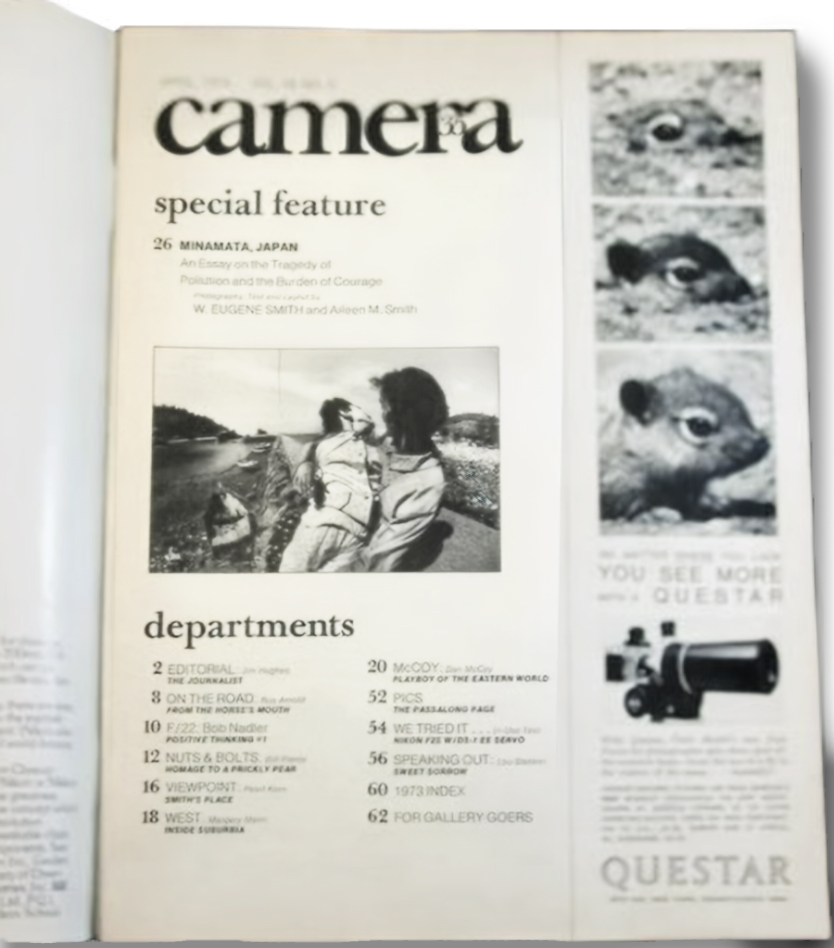

“I have written that Eugene Smith was very particular about prints. This, according to him, was because at the negative stage, a photograph is only 50% of what he imagined it to be. Through utilising every possible printing technique, he brought this percentage up to 100…Also, being told that his prints were great on their own would have never satisfied him. Whether the final presentation medium was a magazine, a photo-book, or a photography exhibition, he was very particular about not only the number of pages and the layout, but also about the text, captions, papers, presswork, and everything else. In other words, it was to satisfy his own principles. As he says, “printing is just one of many processes.” When Minamata was published in Life magazine, he was furious that they changed the title and the layout. And when MINAMATA was published in Camera 35 magazine, he was terribly disappointed with the low quality of presswork. Indeed, it was useless for him to have just his prints acknowledged.”

“People call W. Eugene Smith a perfectionist, but Eugene himself would say, ‘My photographs failed.’ As paradoxical as that may sound, the more the other people call you a perfectionist, the less you think of yourself as one. At least that was the impression I got from being at Eugene’s side.”

Takeshi Ishikawa, born in 1950 on Shikoku Island, graduated in commercial photography from Tokyo Visual Arts in 1972. After the Minamata Project ended in 1974, he moved to New York, assisting with preparing the Minamata work for publication and became a freelance photographer in 1975.

Ishikawa writes at the end of his Minamata Note 1971–2012 that:

“Minamata was an inevitable last stop and a space for the culmination of his journey. The intense time he shared with me there I treasure in my life…After the Goi Incident, [Eugene’s] health had drastically deteriorated and he was literally writhing in agony, but never did he utter any resentment against Japan. He decided not to bring a charge against Chisso in court, because he believed that it would jeopardise the neutrality and fairness of his work if he had become a plaintiff himself. Eugene would often tell me, ‘Minamata will be my last work.’ He extended what was supposed to be a six-month project to three years, and continued to voice that “little voice of photography” on behalf of “those who could not talk, whose hands were bent, whose feet could not walk. Photography is just a little voice, but I believe in its power.”

“In the fall of 1974, the Smiths and I packed up and left Minamata where we spent around three years. There were those among the patients, with whom I became close, who told me, “Mr. Ishikawa, why don’t you stay and take photographs after Mr. Smith leaves?” and tried to persuade me to remain in Minamata. However, I was not persuaded and eventually followed Eugene to New York. There, I made sure of the successful publication of the English version of the photo-book MINAMATA and the exhibition at ICP, and returned to Japan in June 1975. I had no intention of photographing Minamata again as this would be the exact same theme as Eugene Smith.

“In 2008, there was a photography exhibition on Minamata at the Shinjuku Nikon Salon. It was photographer Kazuyoshi Koshiba’s exhibition called “Goodbye and Hello MINAMATA.” I saw some familiar faces there. I told Mr. Koshiba the names of patients I used to be friends with, and asked him to pass on my contact information to them if he ever was to see them again.”

Ms. Emiko Maeda, Ishikawa’s closest friend in Minamata phoned him: “Nostalgia and joy came over me. I felt from the bottom of my heart that I wanted to see them.”

An art museum in Kyoto was holding a special exhibition for the thirtieth anniversary of W. Eugene Smith’s death, noting that W. Eugene Smith died at age 59 and was 53 to 56 when he was in Minamata. Ishikawa, already older than that, realised “it is never too late. I knew I had to go to Minamata” in 2011, forty years since he first went to Minamata with the Smiths.

“Patients who survived Foetal Minamata Disease have all had their fiftieth birthdays, and meeting them again makes me feel as nostalgic as seeing my childhood classmates. People are just as deeply warmhearted, and the Shiranui Sea is as beautiful as ever as it welcomes me back.”

Timothy George notes that an entirely new Japanese edition of Minimata was published in 2021 by Crevis, retaining the Smiths’ original photographs and Nakao Hajime’s translation, but with a greatly expanded postscript that begins with the essay by Ishikawa Takeshi: “Ishkawa is best able to describe Motomura’s suggestion that they come to Japan, their renting a home and setting up a darkroom in Minamata, the making of the famous photograph of “Tomoko in Her Bath,” the beating of Eugene at Chisso’s Goi factory, and the planning and creation of the Life and Camera 35 photo essays and the book.”

Over 4 September–10 November 2018 Ishikawa co-exhibited with Steve McCurry in The Unguarded Momentat Etherton Gallery, Tucson. Etherton Gallery subsequently sold the Takeshi Ishikawa Archive of 100 vintage gelatin silver prints from Minamata by W. Eugene Smith, to the Library of Congress, and in addition Ishikawa and the Gallery donated fifteen portraits of Smith, made in Minamata by Ishikawa, to the library.

Ishikawa has become best known for his long-term work in India. He published Naked City Varanasi in 2020, and a series he has worked on since 1980, on India’s hijra communities, part of an indigenous transgender tradition in South Asia, was published as ヒジュラ : インド第三の性 = Hijras : the third gender of India in 1995 and exhibited at the Center for Creative Photography’s Axial Gallery in October 2023.

3 thoughts on “March 27: Encounter”