February 25: If three photographers’ lives cross on one date they would surely be of a surrealist bent!

February 25: If three photographers’ lives cross on one date they would surely be of a surrealist bent!

This date marks the birth of Fukase Masahisa in Bifuka, Japan in 1934 and also the deaths of German Christian Schad (*1894) in 1982, and Italian Luigi Veronesi (*1908) in 1998.

The two older photographers Christian Schad and Luigi Veronesi were practitioners of the photogram. Tristan Tzara claimed the technique for Schad, punningly calling them Shadowgraphs, since photograms are essentially shadows, and sold a number of them to MoMA on December 3 1937; the term stuck, despite the fact that Schad himself had no idea of its being coined in his honour.

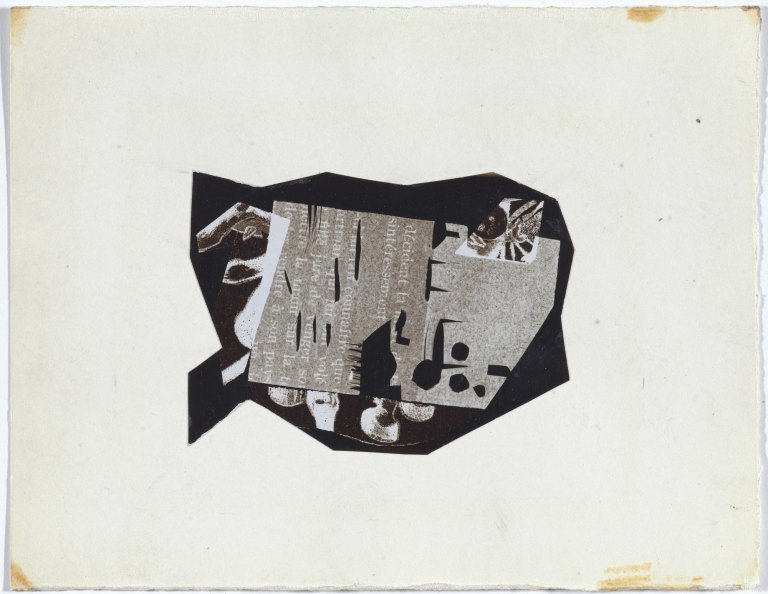

These works in the MoMA collection, a mere cut-out scrap in the case of the above (at 5.9 x 8.3 cm) mounted on a larger sheet, include photographic traces of fragmented texts clipped from newspaper, cigarette wrappers and other sources (below). These hark back to Cubist collage of 1911 onwards which dared use the stuff of everyday life glued to the picture surface. Schad’s works, however, are Dada in spirit, and share Kurt Schwitters’ and Johannes Baader’s interest in salvaged scrap which Schwitters called merz;

My delight in little things carelessly thrown away in the street or left lying around somewhere or other was at its height. I was fascinated by their patina and by the charm of having become unusable that attached to them …

Schad was a painter, not a photographer, and it was in 1919 that Schad’s friend and Dada theorist Walter Serner suggested he experiment with the common printing-out paper that “we used to use in those days” for inspiration.

In his basement apartment at chemin des Roches 2 in Geneva, Schad arranged scraps of paper, small objects, and pieces of common detritus on the POP paper his windowsill, watching as over a period of minutes as the areas of paper exposed to daylight became darker, then fixing them.

In the Schadowgraphs above he has used a printing frame (e.g. left), a glass-fronted picture frame with spring-loaded back which holds the materials in tight contact with the photographic paper, so that we are able to read the sharply rendered text on the scraps of newspaper and cigarette packet (“[NEW Y]ORK HERALD CO., All rights reserved]”), and (“[CIG]ARETTES [GA]UTIER [T]ABAC [MA]RYLAND [Q]UALITE [E]XTRA FINE”).

Many amateur photographers had experimented with the lensless unique-image contact-printed photogram since the earliest days of photography, as Henry Fox Talbot had done to print images of lace and leaves before he was able to produce images with the lens. Schad was the first to turn the technique into a conscious, and radical, art statement.

In Amourette, below, the scraps of material, threads, curtain ring and tape etc. are placed on the paper without a printing frame so that parts of them print out-of-focus. An amourette is a reference to the use of scraps, it means a garnish of pieces of fried spinal cord of veal, beef or sheep; i.e. a mere taste, not the real thing! It can also mean a love affair, perhaps a reference to Schad’s joy in finding a medium which to some extent had its own agency, that ‘made itself’ in partnership with the artist, as the compositions taking form on the photographic paper were only partially visible to him during this process and only seen completely when he discarded the temporary collage compositions. The love affair lasted between September and December 1919 and generated 31 Schadowgrams of which only 23 survive.

These ‘collages’ vary from the cut-and-paste variety of the Cubists and of other Dada artists in that the photogram process transforms and unifies the materials, rendering them negative and thus difficult to recognise, in sepia tones regardless of the colour of the originals, removing the relief of paper on paper, and adding photographic effects of focus and transparency.

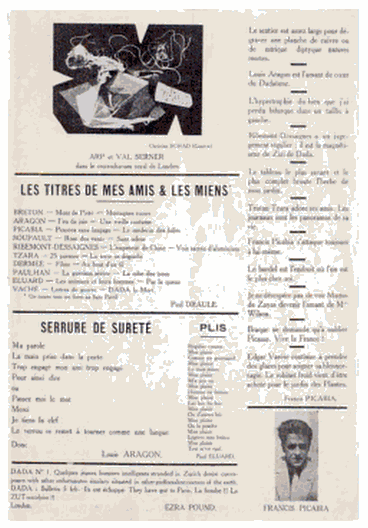

With great excitement Schad and Serner rushed some of the results of these experiments off to Tristan Tzara for publication in the upcoming March 1920 issue of Tzara’s journal Dada which reproduced a Schadowgram with the light-hearted title “Christian Schad (Geneva); ARP and VAL SERNER in the Royal crocodrarium of London.

Despite Man Ray’s protestations it is very likely that he was influenced by Schad’s discovery, through having seen this issue of the journal, or by being informed of them by Tzara. Unlike Shadowgraphs, Rayograms, which were Man Ray’s manifestation of the new medium, were not unique, one-off prints; he usually made camera copies of them.

A signature variation in Schad’s photograms is his cutting of the contour of the image from the given rectangle of the photographic paper, which Schad said he did to ‘liberate’ them from bounds of the paper. The next development for the artist was to employ them as a form of ‘automatic’ art and to reproduce or imitate the photograms in woodcuts.

Christian Schad’s fortunes changed over the next few decades. He abandoned Dada and returned to painting, taking up the style of the Neue Sachlichkeit (the New Objectivity), which was so realist that the National Socialists included it in their showcase of state-approved art, the exhibition Great German Art.

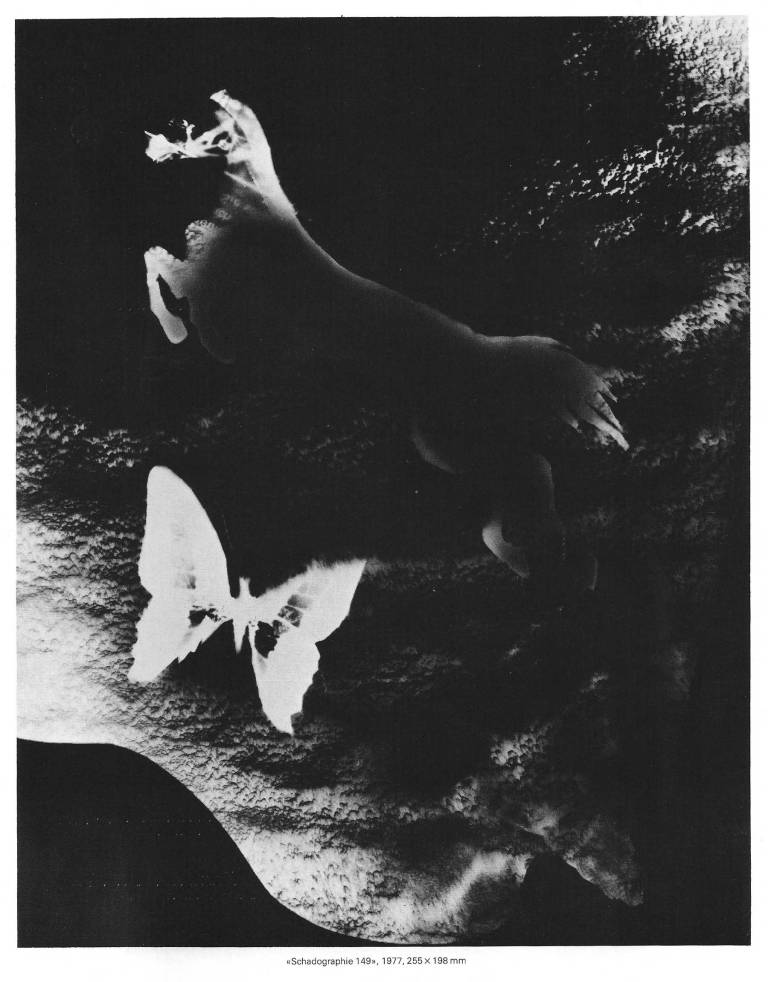

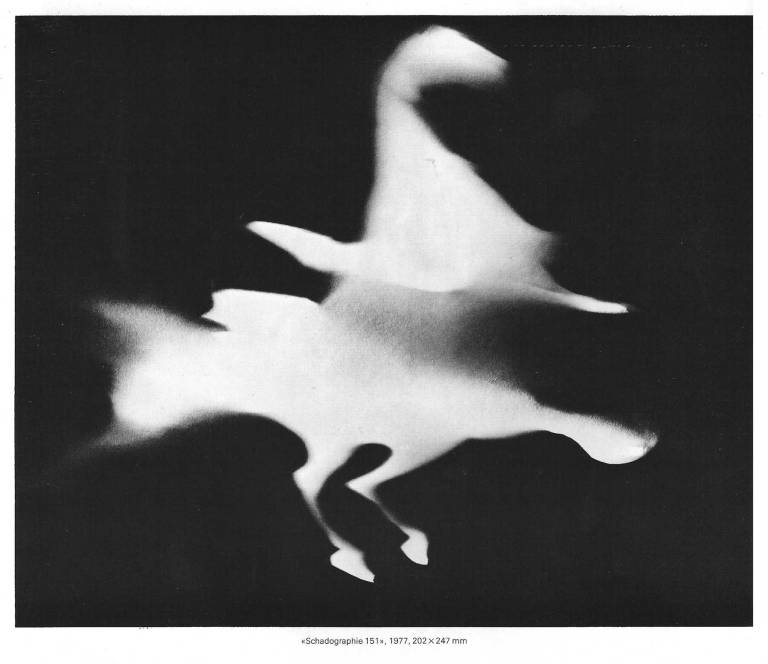

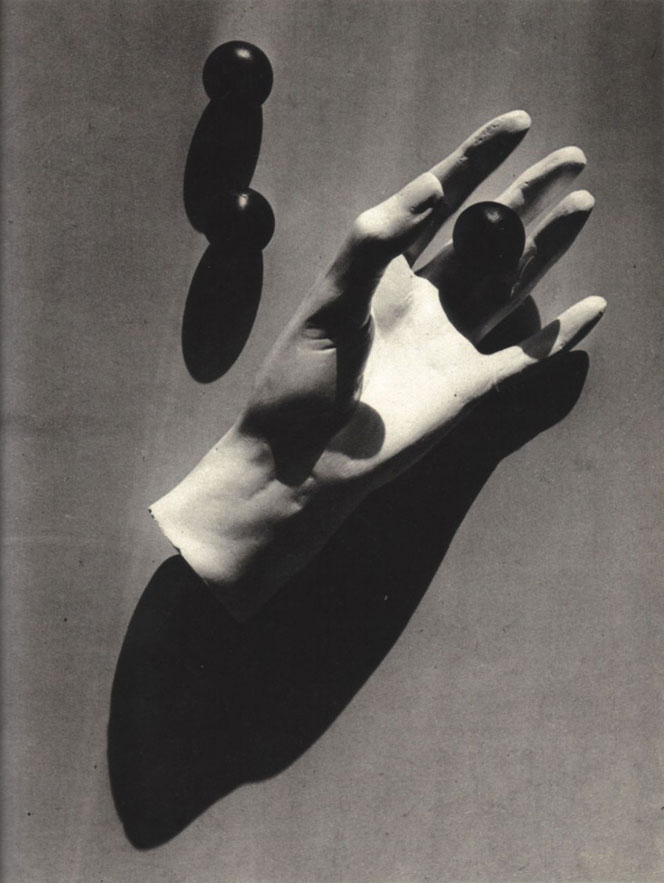

Nevertheless, Schad experienced financial difficulties under the Nazis and survived by running a brewery and working as a theatre critic. It wasn’t until the 1960s that he was ‘rediscovered’ and his painting and photograms appreciated, both critically and monetarily, and he returned to making Schadowgrams. These new works build on and rejoice in the levitation that occurs in the photogram process as materials that rested flat on the photographic paper now appear to hang in blackness as if flying.

These Pegasus-like equine images are representational rather than completely abstract, in the spirit of the ‘magic realism’ that was being belatedly appreciated in his paintings during the 1970s. Their theme of flight is found also in the work of Fukase Masahisa, born in Hokkaido into the family of a photo‐studio owner.

His first solo show, Sky over an Oil Refinery, was in 1960, and after working for an advertising agency, Fukase went freelance in 1968. His Tokyo‐based series Homo Ludens (1971) was followed in 1978 by Yoko for which he obsessively photographed his (then) second wife, Yoko Wanibe.

After thirteen years, she left him in 1976.

In the wake of his divorce in 1976, Masahisa Fukase happened to see a picture of a flock of ravens, symbols in Japanese mythology of disruption and omens of turbulent times, and for him they represented his unendurable heartbreak and forebodings of loneliness and death. His response in grief was to photograph ravens just as fanatically as he’d photographed his wife.

In the prevailing Japanese style of high contrast photography Fukase sought out ravens against the sky at night, and some dead in the snow, the pattern of their black silhouettes like the brushstrokes of traditional Japanese sumi-e.

In the prevailing Japanese style of high contrast photography Fukase sought out ravens against the sky at night, and some dead in the snow, the pattern of their black silhouettes like the brushstrokes of traditional Japanese sumi-e.

Masahisa Fukase’s Karasu (‘Ravens’) series was to occupy him for ten years, and in November 1982, when the eighth and final Karasu chapter was published in Camera Mainichi, Fukase stated that he had ‘become a raven’. He made clear how that felt in images of garbage and detritus, of a drunken man sitting alone and confused among the remains of cherry blossom viewing parties in Ueno Park, and of a tramp on the streets of Tokyo.

Evidently his melancholy journey had not restored his state of contented romantic fulfillment of 1975, but clearly his own family was of great importance to him and sustained his Family (1971–90) which was a document of his parents’ home and family members from a fixed viewpoint, and Memories of Father (1991), of his dying father.

Just before his 60th birthday in June of 1992, Masahisa Fukase fell on the stairway of a bar he frequented, suffering brain damage. Yoko visited him twice a month but he never regained consciousness and would not have been unaware of her presence. “With a camera in front of his eye, he could see; not without.” she said.

The Solitude of Ravens was voted ‘best photography book of the past twenty-five years’ by the British Journal of Photography in 2010.

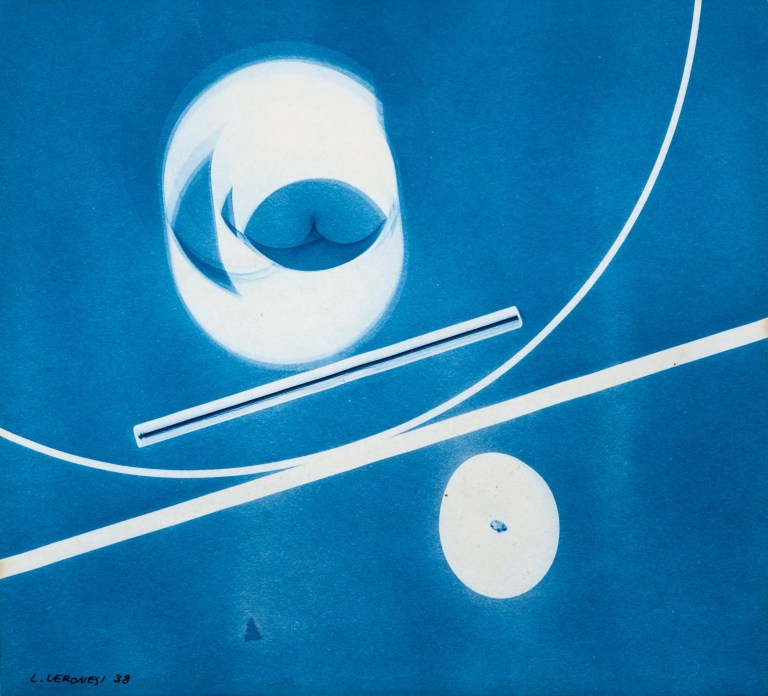

Milan-born Luigi Veronesi discovered his passion for photography and especially photograms in his youth, and went on to produce impressive abstractions in both black and white and colour. Not only a photographer, but also a printmaker, painter, set designer and experimental film-maker, he drew inspiration from Léger’s Ballet Mécanique. His early work touches on Surrealism via the Metaphysical painting of Georgio de Chirico and fellow photographer Giuseppe Cavalli, with whom in 1947 he founded a group named La Bussola (The Compass) with a number of other photographers. Its members aspired to the attainment of a high degree of formal purity in their work, and shared the conviction of the essential ‘uselessness’ of art.

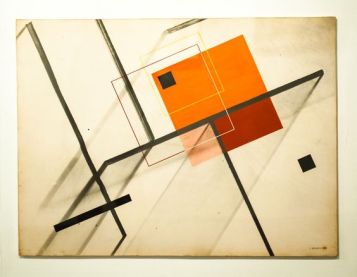

Second to Prampolini, Veronesi was the most cosmopolitan of the Italian artists of this period, well-informed about the international debate on abstraction. He participated in an 1934 exhibition in Paris with the international group of abstract artists in France known as Abstraction-Création, through which he met with Léger, Moholy-Nagy, Vantongerloo, Josef Albers, and Max Bill.

Influenced by Constructivist theories (and politically aligned with Communism), Veronesi worked toward non-representational painting, using the photogram after 1932, and often the more primitive cyanotype, as a means of revealing metaphysical qualities in objects.

Veronesi look the photogram further in large-scale colour images that combined the photographic image with oil on canvas. He prepared a light-sensitive canvas, onto which objects were projected in the dark and then fixed, as the matrix for an abstract painting to apply colour and added drawn geometric lines to enhance the dynamics.

He is unique in the history of the photogram in thus combining painting and photography by bringing the light-sensitive image to the canvas, exhibiting them at the Galerie L’Equipe in Paris in 1938-1939.

Responsiveness to chance through applying original combinations and techniques is what unites these artists who share a date, February 25, but who never met.

2 thoughts on “February 25: Floating”