Historian Françoise Denoyelle, who says she has “always written books that I would have liked to read but couldn’t find,” has just delivered a history of French photographic agencies.

Historian Françoise Denoyelle, who says she has “always written books that I would have liked to read but couldn’t find,” has just delivered a history of French photographic agencies.

Some of them are little-known, but in her austerely encyclopaedic—and unillustrated—Les Éditions de Juillet publication Les agences photo: un histoire française she retraces, in French, the lives of some 350 of them.

Their story had until now been ignored by historians of the press, and only two in photography have made in-depth studies; other works devote pages to the agencies’ iconic staff photographers, and briefly discuss their history. For the first time, historian Denoyelle offers a complete account of the history and influence of photographic agencies in France.

French photo agencies appeared at the beginning of the 20th century coincident with the capacity to reproduce photographs in print through the halftone process which marks the passage of our medium from the studio print to the page, and from the private sphere to the public for whom they provided first-hand information. The function of the agency is to sell pictures at a profit, so though other ethical and aesthetic considerations might drive different structures in the cases of the state-subsidised Agence France-Presse, and the private companies Rapho, Alliance Photo, Magnum Photos, Viva, VU, Myop, Signatures, etc., only adaptation to the market sustained them, with the result that several which failed to do so succumbed to bankruptcy. For Denoyelle this busts the myth that photojournalists could act purely altruistically as—supposedly—did Robert Capa, for Regards, and Garda Taro, for Life, in covering the Spanish Civil War.

French photo agencies appeared at the beginning of the 20th century coincident with the capacity to reproduce photographs in print through the halftone process which marks the passage of our medium from the studio print to the page, and from the private sphere to the public for whom they provided first-hand information. The function of the agency is to sell pictures at a profit, so though other ethical and aesthetic considerations might drive different structures in the cases of the state-subsidised Agence France-Presse, and the private companies Rapho, Alliance Photo, Magnum Photos, Viva, VU, Myop, Signatures, etc., only adaptation to the market sustained them, with the result that several which failed to do so succumbed to bankruptcy. For Denoyelle this busts the myth that photojournalists could act purely altruistically as—supposedly—did Robert Capa, for Regards, and Garda Taro, for Life, in covering the Spanish Civil War.

According to Paul Almasy, answering in a 1980 article his own rhetorical question La Photo à la Une : qu’est-ce que le photojournalisme? (‘The photo on the page: what is photojournalism?’), there are four types of photo-reporters; ‘the witness,’ who deals in facts described by their camera; ‘the storyteller’ whose photographs form a narrative through an ability to capture the essentials of an event; ‘the journalist’ who seeks newsworthy but not necessarily aesthetic visual information; and ‘the investigator’ who sustains painstaking, longitudinal research on the ground. All of these are just the first link in a chain connecting journalists, darkroom technicians, caption and text writers, the sales department with its couriers, its salespeople and finally the archiving department, and precariously dependent on them and at the mercy, ultimately, of the director of the agency who decides its editorial direction and, in the early days, whose names (Manuel, Rol, Meurisse, Trampus, Vandystadt) became the brand.

After the WWI newspapers and then magazines continued to evolve. From the early 1930s, the market reach of the illustrated press grew, with the number of illustrated Parisian newspapers burgeoning from 60 in 1928 to 82 in 1933, while periodicals increased from 575 to 654. Established periodicals such as L’Illustration and Le Monde Illustrated were challenged by new formats with more modern graphics layouts and with pluralistic ideologies, like Vu (1928-1940), Miroir du Monde (1929-1937), Voilà, subtitled “the weekly report” (1931-1939), Regards (1932-1940), Photomonde (1933-1939), Match (1938-1940).

Leisure magazines covering sport, radio, travel, fashion, etc. and diversification of outlets, enabled new and multiple talents to emerge. With photography establishing its position over other media in the illustrated press, numbers of foreign photographers settle in Paris for political, economic, cultural or personal reasons, and the rise of fascism in Germany accelerated the flight from their countries of origin or adoption of still more, with many setting up their own photography agencies or collaborations in complex networks.

Most are small companies employing only a few people around the founder or director, a photographer like Marcel Rol or an inspired salesperson like Austrian emigré Maria Eisner, a couple of darkroom workers and secretaries who type the captions and handle the invoicing. The photographers must be efficient, fast and respond to the boss’s command without being able to choose their subject, with cyclists ferrying the exposed film to the agency and its latest pictures and copy to client publications, transport later being motorised to cope with more pressing timelines and fiercer competition for premium illustration as a major asset.

Agencies in the early days were served by only 3 or 4 photographers, but each had dozens in the heyday of the three A’s – Gamma (founded 1966) Sipa (1973) and Sygma (1973) – which in the 1980s were very large structures. Simply ‘operators,’ photographers were given no credit on published pictures and they had no right to control the use of their images which were (and remain) the property of the agency. The operator has no room for error; each shot must be able to be used and, until more general uptake of the medium or 35mm formats, the plates, then sheet films, were doled out sparingly to them by the agency in the name of economy and efficiency until digital technology shifted costs to equipment turnover and managing ever-larger archives. Readability, good framing accompanied by an informative caption are favored over the aesthetic effects sought by independent photographers. Professionals trained on the job and moved from one agency to another depending on the opportunities and relations with employers. Denoyelle details working conditions of photographers (shooting, devices, plate sensitivity, laboratory, etc.), transmission and sale of photographs in separate chapters on each agency.

The agencies specialised, depending on its history, its opening date and the evolution of the market, either in illustration, or in news reporting, though sometimes they provided both. Some sold locally while others distributed internationally. Independents who wished to relieve themselves of marketing entered co-operative arrangements with an agency which in some cases also distributed photographs from foreign agencies based mainly in England, the United States, Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany and Japan.

Alliance Photo founded in 1934 was unique as an agency which gave its photographers a degree of independence. The initiative of a group of photographer friends who met in René Zuber‘s studio. Many trained as graphic designers and their style was contemporary and modernist.

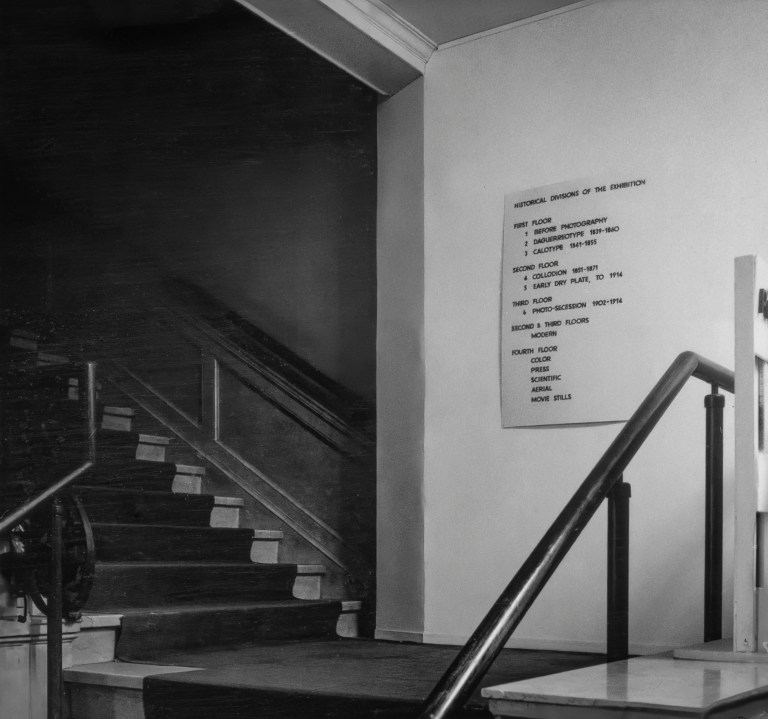

Maria Eisner who worked for the illustrated press from the age of twenty and was trained by Simon Guttmann, head of the very successful Berlin-based agency Dephot (Deutsche Photo Dienst) was responsible for marketing at Alliance Photo. She established an indexing system for the long-term conservation of, and credit for, its photographers’ pictures, so that the agency’s photographers enjoyed a growing reputation both inside and outside France with Verger, Boucher, Feher and Zuber participating in an exposition Affiche Photo Typo, and Bellon, Boucher, Feher and Verger being invited by Beaumont Newhall to participate in Photography 1837-1938 at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). Unlike photographers from traditional agencies, but like their colleagues at the Rapho agency, this group of photographers did not deal with current news but produced work less urgent magazine stories.

Between 1930 and 1934 around twenty photographic agencies opened their doors; the arrival of Anglo-Saxon agencies like Keystone in 1927 had changed the market. France-Presse agency, created in 1933 had the capital and technical means beyond that of existing French agencies so could respond to competition from Anglo-Saxon companies which were beginning to dominate. In 1937, it came under the control of L’Intransigeant and tapped into “a worldwide network of correspondents”. Others less advanced nevertheless play an important role: Fulgur, opened in 1933, Alliance Photo in 1934, SAFRA in 1937, the future Roger-Viollet successor to the General Photographic Documentation in 1938, and in the same year LAPI agency was founded on the initiative of Robert Delhay following the first photographers’ cooperative born from layoffs after the major strikes of 1936. DNP was founded in 1939.

For migrating photographers Paris was a market rich enough to meet their artistic demands while providing for their material needs, whether they were photographers when they arrived, like the Hungarian Kertész, or became one, like the Pole Chim. Most are bourgeois who experienced reversals of fortune due to the effects of the Treaty of Versailles, the crisis of 1929, and the exclusion of Jews from many professions, and the rise of Adolf Hitler in 1933 led to a new wave of immigration of photographers, intellectuals and press people seeking to live on skills and connections acquired in the publishing, press and journalism circles in Vienna, Berlin, Amsterdam, Munich, London or New York. Meeting in Paris with compatriots or French people, they establish circles of assistance to foreigners, to Jews, in political, intellectual or artistic organisations such as the Association of Revolutionary Writers and Artists (AEAR), Red Aid, the French National Committee for Relief to Victims of Anti-Semitism, the Association for the Protection of German Writers in Exile (Schutzverband Deutscher Schriftsteller im Exi, SDSE). Wrote Brassaï in a letter to his parents in 1924;

“I came across quite a few Russians, Hungarians and even Germans that I know from Berlin, but still few French connections. It’s true that I haven’t made much effort in that regard. I only frequent the Rotunda where, in the evening, we are in the company of French, Germans, Russians, Spaniards, Africans and all the nationalities that exist in the world.”

…and like him, in search of professional opportunities, the immigrants frequent the cafés of Montmartre, Montparnasse, Saint-Germain-des-Prés and in the press district near the Stock Exchange, though as exiles, their lives become increasingly precarious with the end of the Popular Front government. Several create their own photography agencies and become image distributors; Russian David Rapoport founded the Rap Photo agency in 1924; Hungarian Alexandre Garai, the Keystone agency in 1927; American James Legrand, the Wide World Photo agency, in 1927; Englishman André Glattli, the Mondial-Photo-Presse agency, in 1931; Hungarian Charles Rado, the Rapho agency, in 1933 (taken over after the war by Raymond Grosset); Luxembourger Antoine Koch, the Fulgur agency, in 1933; Austrian Walter Schostal, the Schostal agency, in 1933; the Hungarian Lucien Aigner, the Aral Press Service agency, in 1934; the Germans Hans and Kurt Steinitz, the Central agency in 1934; the Italian Maria Eisner, prior to Alliance Photo, created the Anglo-Continental Service agency, in 1934; the Greek Robert Cohen, the International Agency of Illustration for the Press, in 1935; the Belgian Pierre Hermans, the agency Les photographes associés, in 1937. Denoyelle investigated the forty-three agencies set up between 1900 and 1947, and found that less than half have one or more French founders.

Having created their agency, Charles Rado, Walter Schostal, Robert Cohen, or Alexandre Garai worked with the French press, but also international markets, making contact through their multilingualism, their pluricultural training, like polyglot, Maria Eisner, founder of a short-lived Anglo-Continental Service, who in four languages worked with the United States as well as Austria; or the Hungarian Geza Sterm, founder of the Lutetia agency, fluent in Hungarian, German, English, French, Esperanto and could understand of Italian and Spanish; or the ten Garai brothers who, after founding the Keystone agency in New York, set up offices in London, Berlin and Paris. Hungarian Lucien Aigner, founder of the Aral agency, was Stefan Lorant‘s assistant. Independents like Gorta provide liaison between small agencies (Anglo-Continental Service and Black Star) which attract the most creative photographers.

Capa, future founder of Magnum Photos, but still unknown at the time, was in contact with Imre Rona, a Hungarian, director of the ABC agency in Amsterdam which would distribute Magnum Photos photographs after the war. He met Fritz Goro in Vienna. The latter introduced Capa to the founder of the agency Hug Block for whom he worked for a few months. The cousins of Gisèle Freund, Hans and Kurt Steinitz, founders of the Central Agency, hired Ladislas Czigany known as Taczi Tigany, friend of Capa, to take care of the laboratory. It is in this crucible of small agencies – more about DIY, economic survival, mutual aid, friendship and enthusiasm for photography, the press and its many possibilities and opportunities – that is forged the idea of a better structured agency, more concerned with the material interests of photographers and the recognition of their work. From the Central Agency to Alliance Photo, via the Anglo-Continental Service, the Hug Block agency, the organization of a new structure to distribute photographs is gradually being developed. At the end of the 1930s Capa removed from his projects the term agency carrying too many disappointments, obligations and unfulfilled commitments before finally founding Magnum Photos Inc. in 1947.

The photographic supremacy of Paris was recognised abroad; Denoyelle points out that in 1937, the great centennial survey the international Exhibition of Photography 1839-1939 organised by Beaumont Newhall at the Museum of Modern Art in New York featured thirty photographers living in Paris out of the seventy-seven exhibited in its contemporary section.

The arrival of German troops in France, broke this great momentum. Smaller agencies, other publications and propaganda in the service of the Vichy government were set up by apologists of Pétain and advocates of Collaboration. From September 1939, the network of photography agencies was disbanded, foreigners begin to leave the country or were incarcerated, and the French are mobilised.

In June 1940, most agencies had to close and new ones provided the German authorities and publications with propaganda promoting German National Socialism. The photographers of the Fulgur agency working for the press in the northern zone and the southern zone were mobilised when war was declared so it had close but it reopened in January 1941 and provided photographs to sports newspapers and the Parisian press: Paris-Soir, Le Franciste, Au Pilori.

Charles Nobile‘s Nora agency, a device of the Germans for perpetrating their propaganda in the southern zone, failed and was closed in 1943. SAFARA, a group of old agencies, and Silvestre whose director replaced his former boss Henri Manuel, were despoiled by Pétain’s anti-Jewish laws, as was the Trampus agency which provided a notable part of Pétain’s propaganda in Paris and Vichy France, and the Keystone agency, run by the Jewish Garai family, under the name Gallia, offered the same service during the Vichy regime while participating in the Resistance.

After the Liberation, new newspapers with titles often from the Resistance, enabled other agencies to emerge despite the high price of paper, manufacturing costs, and the weakness of advertising market, and rationing of electricity to dry the photographs, coal to fuel the stoves, paper for captions and envelopes, photosensitive products, and petrol for travel. During the period of the reparations, the finicky Ministries of Information and the Interior control authorisations to open agencies, the product quotas, and licences for photographers. All agencies active during the Occupation were closed and trials investigated the sharing of intelligence with the enemy and illicit profits, putting an end to the existence of most of the agencies which collaborated: DNP, Fama, Fulgur, Silvestre, Trampus. Many, like Keystone and Rapho, resume their activities after having been aryanized as do ABC and Lapi.

In May 1947, Robert Capa organised a meeting over lunch at the Museum of Modern Art in New York with Eisner and LIFE magazine’s Bill Vandivert and his wife, Rita, to establish Magnum Photos, Inc. realising his vision, but only because Eisner, as the only one with any previous experience in such a venture, was able to organise and market the work of multiple photographers, and establish the archives and the office systems, including the use of contact sheets. Henri Cartier-Bresson and George Rodger were not told of the meeting, but were nevertheless made Magnum’s vice-presidents, and on a detour to Paris, David ‘‘Chim’’ Seymour received Eisner’s telegram: “You are Vice President of Magnum Photos. Detailed letter sent to Paris on May 22nd. I will soon have interesting assignments for you.” The seven members became shareholders and Magnum had offices in New York, to be run by new president, Rita Vandivert and in Paris where Eisner was appointed secretary and treasurer and head at 125 rue du Faubourg St Honore, from where she had run Alliance before the war. When Bill and Rita Vandivert left Magnum in 1948, Eisner, then engaged to Hans Lehfeldt a doctor living in the United States, was made president. Magnum Photos’ Paris office retained her large, fourth-floor apartment at 125 Rue du Faubourg St.-Honoré, convenient to Capa’s rooms at the Hotel Lancaster, so that he could use the office to make phone calls and dictate copy for his photo-stories. In New York, the office building was moved to West 4th Street, between Fifth and Sixth Avenues, smaller, but close to the Algonquin, where later, Capa, whose administrative style was more relaxed, liked to lunch.

Respect for captions and images is at the heart of Magnum’s approach, establishing new commercial relationships with the press by offering complete reportage that asserts their vision of the world in place of autonomous images.

Before surveying the 1970s era and the rise of digital imaging in the 90s, Denoyelle in her introduction looks back over half a century in which photography has established itself in the news press and many photographers whose photos now belong to the collections of major museums developed much of their work by responding to commissions from agencies.

She asserts that it was in the 1950s that reporting experienced its greatest successes around Cartier-Bresson, Werner Bischof, Elliot Erwitt, Ernst Haas, Erich Lessing, Inge Morath, Marc Riboud, George Rodger, Eugene Smith, Denis Stock and their colleagues at Magnum Photos, on the one hand, and in the movement of the Rapho agency, on the other hand, with photographers like Jean Dieuzaide, Robert Doisneau, Janine Niépce, Willy Ronis, Sabine Weiss… while others, like Dominique Darbois, Jean Marquis and Jean Mounicq, having briefly passed through an agency, prefer to regain their freedom and work directly with the press and publishing. The arrival of television in the 1960s-1970s will put an end to in this early age of photojournalism before two behemoths take over: Sygma (1973-1999) and Sipa (1973-), which with Gamma, form the “Three A’s”, and reassert French predominance over photojournalism.

In subtitling the book “A French History”, Denoyelle’s motive was to restore the French reputation;

“People are constantly talking to us about American photography and telling us that elsewhere, it’s better than here. But in the 1930s, it was Paris that created the agencies, for economic reasons first and then politically. All the photographers from Eastern Mitteleuropa converged first on Berlin and then on Paris, which meant that Paris truly became the capital of photography. There were a lot of agencies set up by emigrants. And secondly, at the time of the three A’s, the American media were obliged to set up offices in Paris to be in more direct contact with these three agencies. For a country that is not that big, France still has a great history with agencies.”

My reading of French is very slow and the above is only an outline of the content of this comprehensive book based largely on the introduction, but only the first part of the history covering 1900-1947 and including chapters on the first agencies (1900-1905); the birth of photojournalism and the agencies of 1919-1940; Parisian photo agencies between the wars (1919-1940); American agency offices between the wars (1919-1940); the Aryanised agencies (1941-1944); the agencies of the north and south zones (1940-44); the post-war French and post-war American agencies (1944-47). The second part, from page 384 and constituting almost half the 650-page volume, covers the 60 years 1947-2007. There is an index of photographer names by which one can trace their careers in agencies and as independent operatives, and an appendix listing less significant agencies. This is monumental feat of research.

Françoise Denoyelle holds degrees in Modern Literature from the University of Reims and in History from the University of Paris III – Sorbonne Nouvelle. In 1991, she defended her historical thesis titled “The Market and Uses of Photography in Paris during the Interwar Period,” supervised by Pierre Sorlin. Since 1989, she has been teaching at the École Nationale Supérieure Louis-Lumière, and from 2003, she has held the position of University Professor. Between 2003 and 2015, she presided over the photographers’ collective, “Le Bar Floréal Photographie.”

From 2004, she has been a member of the Donors and Rights Holders Committee of the former photographic heritage, under the direction of Architecture and Heritage, Ministry of Culture and Communication. She also served as the president of the Association for the Defense of Donors and Rights Holders of the former photographic heritage from 2004 to 2011. Denoyelle has authored numerous books and prefaces. She is a member of the reading committee and later the scientific committee of “Études photographiques,” a journal published by the French Photography Society. She also contributes to the “Cahier Louis-Lumière” journal, published by ENS Louis-Lumière. Since its inception in 1998, she has been the editor-in-chief of the digital journal “Du sel au pixel,” produced by ENS Louis-Lumière students during the International Photography Meetings in Arles and later during the Paris Photo Month.

I had missed all awareness of this book. Thank you for bringing this very useful-sounding scholarly work to my attention.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes an excellent resource that, with much labour, has brought together data that is otherwise very scattered and difficult to pin down. I do hope an English edition comes out. The little French publishing house got the book to me in Australia very quickly…they’re building a worthwhile inventory.

LikeLike