Consider this; an extraordinary intervention by the state in art, dictating what is good and bad, with government authority to determine what will be allowed in exhibitions and what sent overseas to represent the country.

Consider this; an extraordinary intervention by the state in art, dictating what is good and bad, with government authority to determine what will be allowed in exhibitions and what sent overseas to represent the country.

Surprisingly I’m, not talking about some Deep South American book-banning state like Texas, nor is this a manifestation of Mao Zedong’s famous 1942 dictum; “There is in fact no such thing as art for art’s sake, art that stands above classes or art that is detached from or independent of politics,” which in its sense is quite valid, though so strictly applied during the Cultural Revolution as to become a crippling dogma.

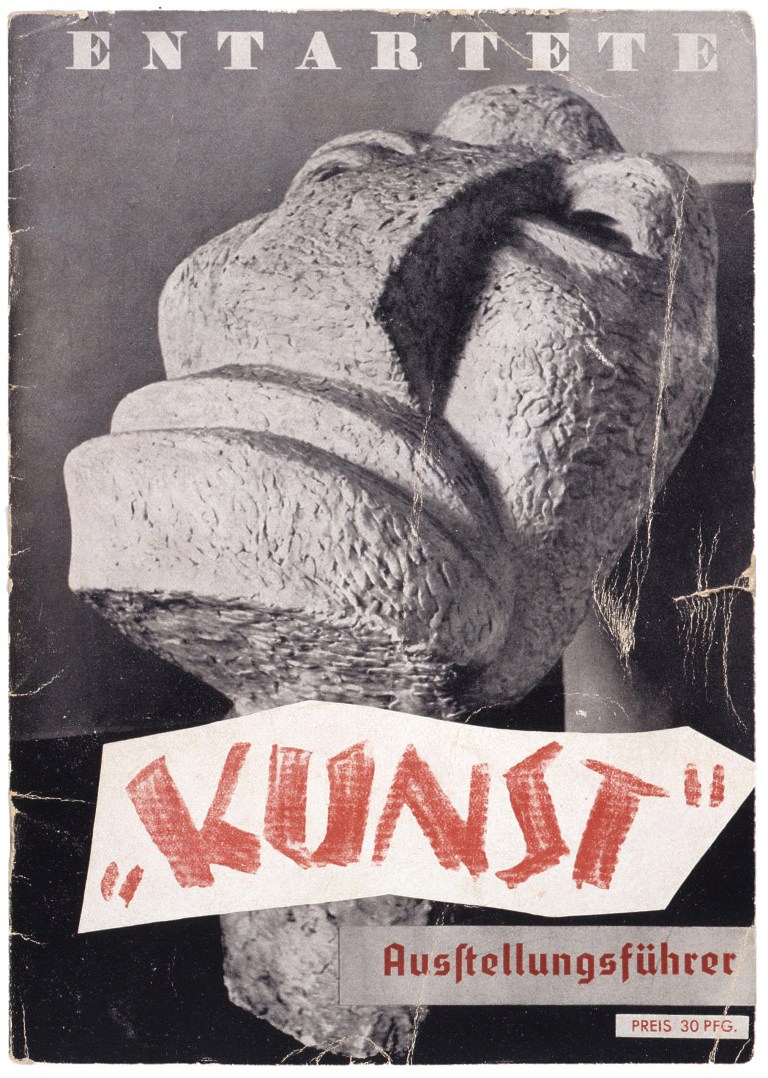

This particular encroachment of state into the realm of art is a phenomenon contemporaneous with Hitler’s favourite painter and “Specialist adviser for fine arts” Adolf Ziegler. Hitler’s Haus der Deutschen Kunst (‘House of German Art’) was constructed to showcase art of the Third Reich and opened with the Great German Art exhibition of 1937 with a selection of muscly Teutons in a neoclassical academic style. Simultaneously, over the road from the Haus der Deutschen Kunst, Zeigler curated his Entartete Kunst (‘Degenerate Art’) exhibition, on the catalogue cover for which the camera so unflatteringly distorts Otto Freundlich’s sculpture…

…the latter a man who in his application of cubism predicted digital pixilation, before he was betrayed by the Vichy government and murdered on arrival at the Nazis’ Lublin-Majdanek concentration camp in Poland, and whose radicalism has only since 2010 been the subject of appreciation.

No, I’m writing about Australia. No-one was imprisoned or executed, but 1937 did see the government of the day assume authority over art.

There is a photographic way into this development; first with a line-up of its instigators by Les Dwyer (1893–1962), owner of Canberra’s first, and possibly the longest running, “photographic stall” at the Lawns in Manuka from 1929, and an increasingly frequent contributor to The Canberra Times.

It helps to know who is behind the camera, don’t you think? He looked rather like his subjects, one of Menzies ‘Forgotten People’ of

“the middle class – those people who are constantly in danger of being ground between the upper and the nether millstones of the false class war; the middle class who, properly regarded, represent the backbone of this country,”

and who later became John Howard’s “Battlers” and Scott Morrison’s “Quiet Australians”… fictions who apparently couldn’t speak for themselves, or were conveniently too nice to do so. That’s who these men, and one woman (sculptor Daphne Mayo) are looking down on…

We see them, men with one woman, arrayed in self-satisfied poses in front of the Canberra Hotel where earlier, in the smoke-room, they had founded the Australian Academy of Art. The chief proponent stands, dominantly but casually, right of centre in the front row. He is Robert Menzies, then Attorney-General, who became Australia’s longest-serving Prime Minister for a total of 18 years from 1939–1941 and 1949–1966 (until I was 15 I knew no other) and who was a prime mover of the new, conservative Liberal Party. In August 1936, in the then establishment newspaper The Argus (which in 1949 moved left to oppose Menzies) he had made his intentions for art clear ;

BEAUTY IN ART

Mr. Menzies’ Views

“During my journey through Europe I had the opportunity of looking at a number of pictures.” said the Federal Attorney-General (Mr Menzies), when he opened Mr William Rowell’s exhibition of paintings at the Athenaeum Gallery yesterday. “I went through the galleries of the Louvre and some of the great galleries of Holland and I also saw some of the surrealist work in London so that I can say that I have seen some of the finest pictures in the world and also those that must undoubtedly be among the worst.

“I cannot help being struck by the quality of Mr Rowell’s work when contrasted with the singularity ill-drawn pictures of modern art, described by their authors as having a symbolic value unintelligible to the un-illuminated mind,” Mr. Menzies added. “My own Philistine philosophy is that there can never be great art without great beauty. It may be beauty of the commonplace or beauty of the sublime but there must be beauty. Mr Rowell seems to be an artist who has attracted a great deal that is good from modern art but has preserved the permanent canons. He has shown us that portraiture can be finally stimulating and exciting.”

Will Rowell was that year announced winner of the Archibald Prize for portraiture for his oil painting of organist William George Price.

Was this what Menzies sought for Australian art, this gravy-brown, stolid portrayal of the self-satisfied voluptuary? Hugh Adams, associate editor of Melbourne’s The Herald (and in 1938 a pall bearer at the funeral of the all-Australian journalist, poet and raconteur C.J. Dennis) reported at length asking…

Adams’ main argument was that the sparseness of Australia’s population of artists would result in a mediocre standard being set by this academy, which unlike the Royal Academy to which it aspired, would not be a teaching institution, but merely a vehicle for a chosen few establishment artists. He asserted that the “proposal for an Australian Royal Academy of Art appears to have had its birth in the tiny art centre of the Artists’ Society of Canberra,” who had got into Menzies ear to plant the idea that any centre of art should be in the parliamentary territory.”

“More than anything else at the present time,” he wrote, “Australian artists and the Australian people need to see the good work of artists of other countries,” so railed at “the stupid application of revenue duties to all works of [imported] art” that denied such a stimulus, a “blockade” that he felt an Academy would maintain and strengthen “in order to force upon the public the Australian standard accepted by […] artists banded for their protection against any effort to let Australians share in and learn from the living, inspiring movements in the art centres of the world.”

“It is obvious that if an Australian Royal Academy were to hold sufficient power and authority in an art world so restricted as Australia’s it would have to adopt dictatorial methods and suppress any of the signs of revolt and rebellion from which nearly all great art is born […] At its very best the Royal Academy proposal seems to threaten us with a smug dictatorship over Australian artists and over the Australian public as to what is to be accepted as a standard of good art. At its worst it seems to threaten us with a commercially-minded conspiracy to raise the prices and ensure the sale of the mediocre works of the members of a mutual benefit society.”

Modernist artists rebelled. The Painter-Etchers’ Society of Australia in February 1937 protested to the Governor-General over “the dictatorship methods of the self-elected R.A.A.’s” George Bell in Melbourne at a March 1937 meeting of the Victorian Artists Society, attended with discomfort by several who had been invited to join the Academy, protested that “The whole project up to now has been so shady and so specious that we should look on it with very great suspicion,” and set about creating the Contemporary Art Society of which he became founding president. Consequently even some of these members of the new Academy revolted; at Menzies’ opening of Victorian Artists Society autumn exhibition on 27 April 1937 at which he condemned modernity in painting as “doing all that great artists wouldn’t have done,” like making “a face look exactly like a cabbage, or a cabbage resemble a face,” president of the VAS James Quinn indignantly attacked Menzies, pointing out that Rembrandt himself was a rebel; “Instead of painting for buyers he painted to please himself as an artist and, accordingly, ‘went broke.'” Menzies and Bell continued sparring publicly over the issue in the press.

Against such opposition to the idea, Menzies application for a Royal Charter for his Academy foundered, and the organisation lasted only through the war years, and by 1947 was no longer, though as you can read in the Wikipedia article I have written on the Academy, Menzies stultifying influence on Australian art continued into the 1960s during his prime-ministerships. Nevertheless, the advent of modernism in Australia decades after its rise in Europe and America proved unstoppable, and indeed was already underway, at least in photography.

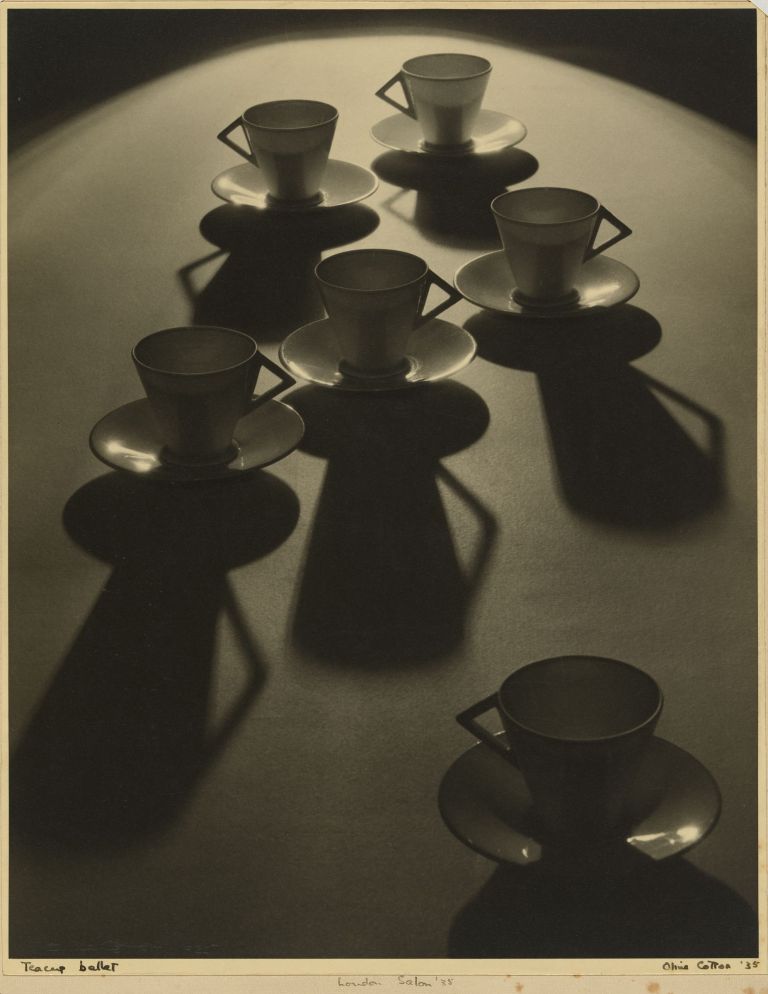

Olive Cotton was experimenting in Max Dupain‘s studio, producing modernist works like Teacup Ballet (1935) and surrealist montages. Five months after the founding of the Academy, and right under Menzies nose in the parliamentary library from which this issue comes, the magazine The Home sports this faux ‘pop-up’ cover design by Douglas Annand using a montage of modernist photographs representing the capital cities; a rooftop dutch-tilt view of a busy street, night shots and an aerial shot of city blocks, all set within three-dimensional solids on a stylised letter ‘a’ on a saturated yellow ground.

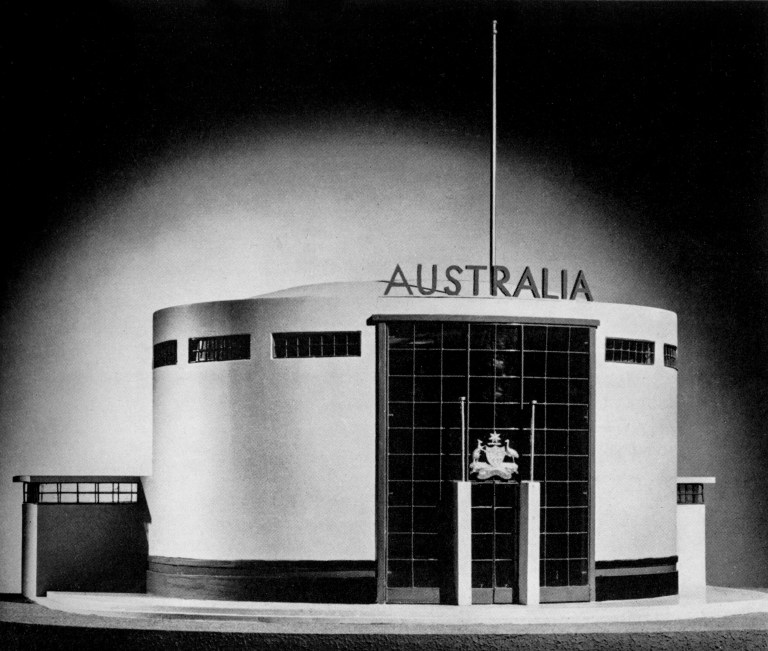

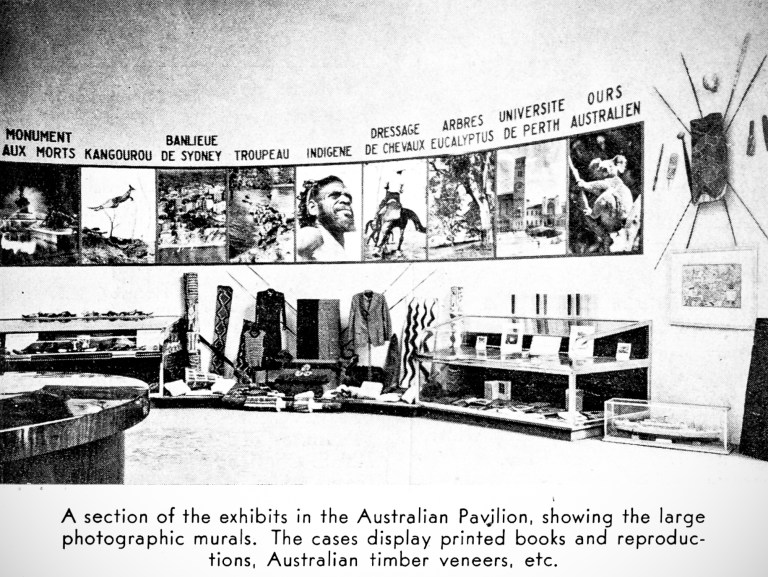

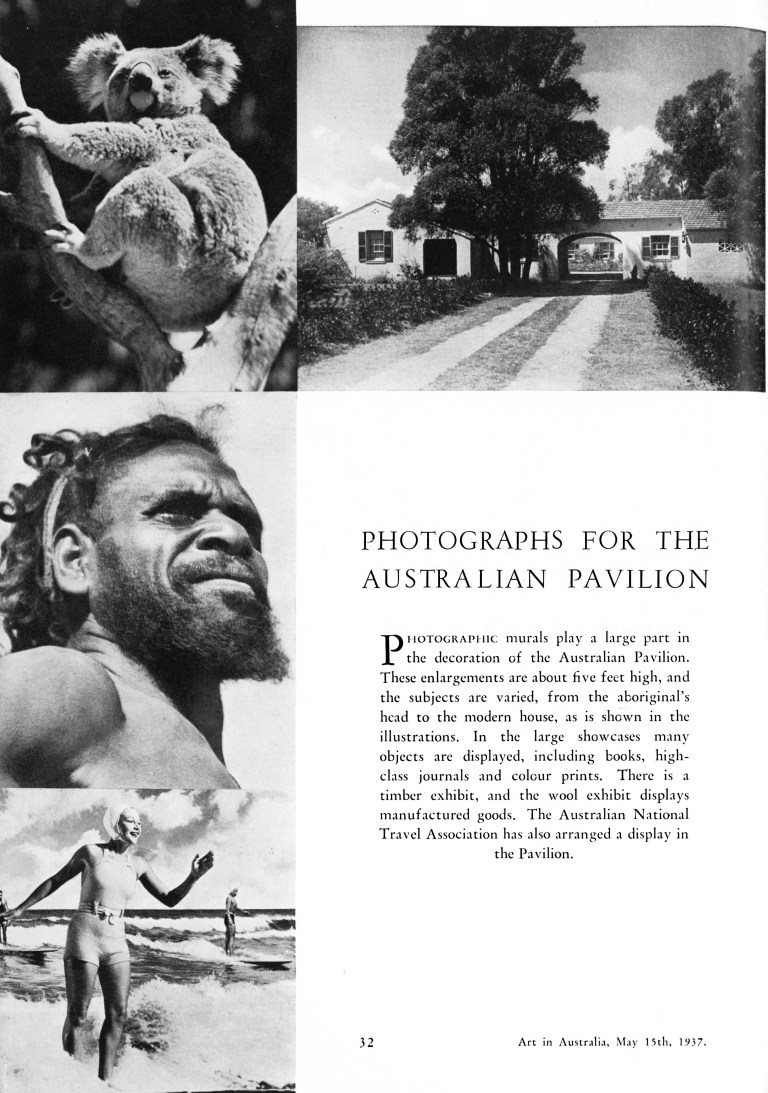

Within the magazine is a story on the Australian Pavilion at the 1937 Paris Exhibition, its interior ceiling design also by Annand. It is useful to compare the displays inside the building which attracted favourable attention, despite a tardy and reluctant government response to participating in the French Exhibition, and criticism back home that it did not present Australian tinned produce as had usually been done at all prior expos.

Photography featured in boldly labelled mural arrangements above stands displaying Australian goods and indigenous artefacts. Research by Daniel Palmer and Martyn Jolly into this event reveals that though Sydney Ure Smith, founding member of the Art Academy and editor of Art in Australia, was on the advisory committee, The Sydney Morning Herald compared the frieze of photographs that it was; “notably fine … the most impressive pictorial advertisement the Exhibition has to show,” more favourably against the “immeasurably dull canvases” which were “far more photographic than the photographs, and much less strikingly impressive.” For art historical context Palmer and Jolly remind us that “the Republican Spanish pavilion debuted Picasso’s Guernica at the same event.”

Art in Australia also reviewed the Australian imagery in the pavilion, illustrating its article to provide us an opportunity for further comparison of paintings with photographs, which confirm that impression. A member of the Academy like many of the other exhibitors, Elioth Gruner contributed a 1931 oil Sheep Country, a prosaic view of over-cultivated, dry and uninspiring rural landholding, titled not for a landscape as idyll, but as agricultural acreage.

That the Australian National Travel Association, publishers of Walkabout were involved is clear from the inclusion of photographs commissioned by them and also used in the magazine, their arrangement in the display overseen by advertising photographer Russell Roberts, a friend of Cotton and Annand, joining the latter with Max Dupain in the Camouflage corps during the war.

A candid response to the quality of the Academy artists’ work can be found in an article “The Camera v. Academies” by the Western Australian novelist Frank Rhodes Farmer in the December 1941 issue of Pertinent, one of Australia’s many ‘little magazines’ of the era;

Rarely do I visit Sydney; but, one day, I went up to see the Australian Academy of Art at the ducation Gallery, it depressed me. Was I in a bad mood? Should I dare go onto a Miniature Camera Group Exhibition at the Blaxland Galleries? Surely, if the best paintings of 1941 bored me, then photographs would be insupportable.

I regret to admit that I came away from that exhibition of photographs aglow with enthusiasm. Why was I bored with paintings yet transported by photographs? Is it because we are jammed bang in the middle of the machine age? Do our brilliant young men turn to a form of art that is mechanical? Certainly, these photographs were full of fire; minor works of art. The artists had ideas. They expressed them with an Oriental simplicity of means. They saw life freshly, with enthusiasm; and from new angles. To them a few footsteps on the sand expressed more excitement than did a whole range of mountains to reverend seniors of the Academy of Art. Also, rightly or wrongly, the photographer had the feeling that the work was of practical value to society.

Do not imagine that I prefer photographs to paintings. The worst of paintings becomes a friend; the best of photographs a bore. Many photographs in the Blaxland Gallery smacked of exhibitionism. Yet the enthusiasm of the photographer was so acute, so fresh, that not one picture appeared vulgar. These camera men rose to Allegory. They sank to puns. But never, never were they bored. Indeed, in them appeared that same enthusiasm for life, for the new, fresh angle, as in Giotto, Chaucer, Shakespeare.

Why then does the Australian Academy of Art lack this freshness, this new approach to life, this enthusiasm? Certainly the photographer with cheap, small films may take one hundred pictures to gain one effect. But the artist has, or is supposed to have, a mind trained to aesthetic appreciation; he knows immediately what is pictorially valuable, what is dross; he has great technical skill; he has studied painting as an exact science; indeed, he is a professional; while the photographer usually is an amateur. Above all, the painter has at his disposal the inestimable privilege of colour; a palette glorified by Titian, by Vermeer, by Cezanne. The photographer may gain a striking effect; the artist with his oils can—and/or should— penetrate to the very soul of form. One remembers with pleasure an exhibition of Canadian paintings at the National Gallery, Sydney […] Canadian painters apparently found it exciting to be alive, and exciting to be alive in Canada; they showed themselves in intellectual ferment, striking from themselves and from their country an expression as full as lay within their power. Can one honestly say the same of the Australian Academy of Art?

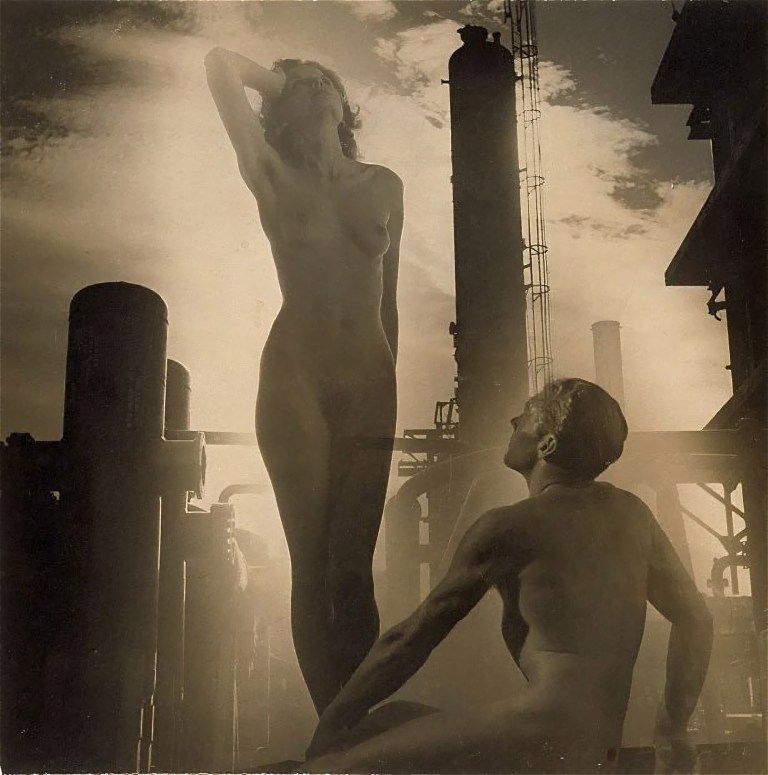

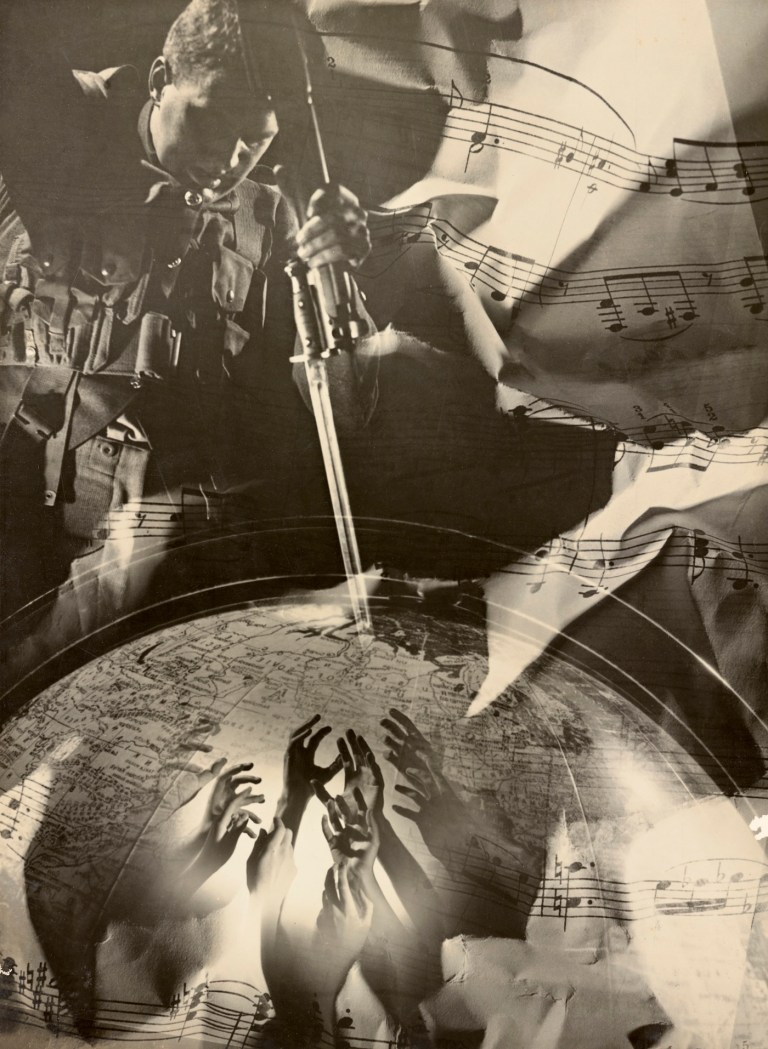

Farmer refers to the second exhibition of the Miniature Camera Group which began in 1938, with photojournalist and fashion photographer Laurence Le Guay a founding member, in whose photomontage The Progenitors a surrealist mingling of the industrial and the figurative is evidence of the Group’s credo to support and encourage “picture-making…in ways other than what is usually called, pictorial photography.” That was made possible by the more portable camera, such as the folding Kodak, the Rolleiflex or Leica; the Group limited formats used by members to 2¼ inches square and smaller. The advent of Kodachrome 35mm slides for projection expanded their medium into colour.

Their first exhibition was opened by the Lord Mayor who said that “all the exhibits showed a modern tendency, but they were of a high photographic standard” and work, especially by J. W. Metcalfe, Henri Mallard, Laurence Le Guay and J. Andriesse, was heralded in The Bulletin as of a quality “equal to that attained anywhere in the world,” and caused a Sydney Morning Herald reviewer to wax poetical;

Early meetings included discussions such as “Art versus Photography” but its cutting edge was dulled by the War, members dwindled to about 30, and in 1948 the group was subsumed without protest into the Camera Club of Sydney since it was a club itself and had soon employed the same system of competitions, trophies and ‘gongs’, and incestuous imitation of winners that hampered innovation and bred stagnation.

Thus, photography, isolated from the mainstream of traditional art, was not immune from the argument from retrograde conservatives among Pictorialists still holding out in the Sydney Camera Circle who declared, in the words of Arthur Smith (echoing Menzies’ pronouncements on painting); “Ultra-modern photography, like ultra-modern art, is but the expression of mob revolution.”

The modernists in response briefly formed the ‘Contemporary Photography Groupe,’ with a French flourish added in the final ‘e’ by Cecil Bostock, a founder with Max Dupain and his partner Olive Cotton. They were joined by William Buckle, Harold Cazneaux, Damien Parer, Laurence Le Guay, George E. Morris and Russell Roberts, and designers Douglas Annand, A.E. Dodd and Louis Witt. Le Guay criticised post-WW11 salons for ‘not displaying the vitality and new creative spirit’ and pronounced that “pictorialism had stagnated,” a conclusion with which Cazneaux reluctantly concurred. The group held its one show over November and December in the Exhibition Gallery at David Jones’s Market Street store, Sydney, but their activities were interrupted by World War Two after which in 1946 Le Guay founded his magazine Contemporary Photography which survived until 1950 when his commercial and fashion photography business proved too busy.

While Australian easel painters in a crowded market either stubbornly resisted, or tentatively toyed with modernism, photography largely escaped their attentions, and that of the Academy, except where it posed a threat. Art in Australia edited by Academy stalwart Ure Smith printed the word ‘photography’ a bare ten times in the decade 1930-1940, and only to comment on its utility, with sculptor Rayner Hoff dismissing it in a 1932 issue as “merely a process” that “saves trouble,” or as a competitor to ‘real’ art, as in Lionel Lindsay‘s lament in 1937 that “so ‘journalesey,’ so degraded has drawing become as the slave of sensational journalism and swift production. The fine illustrator has gone the way of the old actor who ‘played with Irving’—both have been crowded out by photography.”

Room on the Art in Australia letterpress-printed B.J. Ball art paper was given in 1935 to an article “Artistic Photography in Australia” by Harold Cazneaux extolling the virtues of Pictorialism and “the oil pigment and bromoil methods wherein the artistic worker may replace the photographic image on paper by one of pure pigment, and with a remarkable latitude in the control of tonal qualities may modify the drawing by suppression or by removal of unnecessary detail or objects. If he so wishes he can make composite prints to gain his ends in producing a picture. It is also possible to transfer these pigmented photographs by means of a transfer press on to any grade of art paper.”

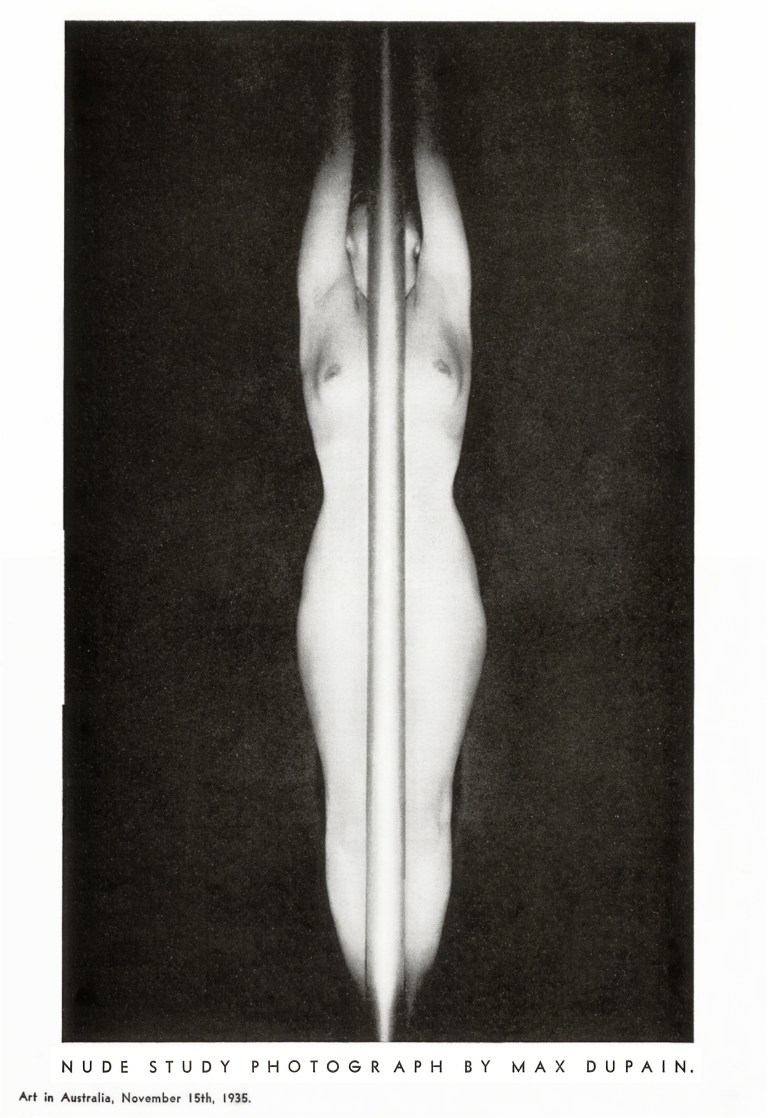

In the November issue that year Max Dupain was given room to assert that “We must believe in photography […} as a new medium, with its mechanistic and not naturalistic forms,” and on seven pages reproduced his abstractions of nudes, faces and hands and a New Objectivity study of morning light through an empty milk bottle.

Looking back at the 1930s decade we can see that the emergence of art photography from under a pall of stultifying conservatism covering the isolated continent of Australia was made possible by its diversity of uses and outlets. The easel painters, restricted to a market only in selling work to hang on walls, had to cater to prevailing tastes, while modernist artists’ efforts to innovate were hampered by those same tastes. Photographers entering that same market were a small fraction of those who were at the same time enjoying commercial success in photojournalism, advertising and illustration.

That set the scene for an increasing acceptance of our medium as art in the following decades.

.

A wonderful article James it really illuminates the times, the concepts and themes. It is so great to have this history at your fingertips. Well done!

LikeLike

Thank you Marcus…always wonderful to have your encouragement!

LikeLike

Fascinating tale, well told!

LikeLiked by 1 person