February 14: With each new technological innovation comes a realisation that the eye is less and less adequate to the task of comprehension.

February 14: With each new technological innovation comes a realisation that the eye is less and less adequate to the task of comprehension.

Some ten years ago I was lucky enough to be invited by an ex-student and onetime teaching colleague Brett McLennan to the opening of Eyes, Lies & Illusions November 2 2006 – February 11 2007, at the Australian Centre for the Moving Image in Melbourne, where he then worked.

The show was assembled from the internationally significant collection of Werner Nekes (1944–2017) who was a German film director who collected everything related to the invention and production of cinema, such as optical toys, laterna magica, wax museums, and much more, the techniques of which he also used in his feature films and in his 1985 documentary Was geschah wirklich zwischen den Bildern? (‘What really happened between pictures?’).

Nekes died on 22 January 2017, having never found a home for a permanent exhibition of his valuable and illuminating collection; the latest possibility to date was to house the collection in an old tower on the site of the former Landesgartenschau in Mülheim (where he died) in which is a camera obscura.

Nekes died on 22 January 2017, having never found a home for a permanent exhibition of his valuable and illuminating collection; the latest possibility to date was to house the collection in an old tower on the site of the former Landesgartenschau in Mülheim (where he died) in which is a camera obscura.

Nekes himself, a modest and sincere fellow in an immoderately long gaudily striped tie, opened the show and answered questions. I returned several times to give myself time to explore the huge array of optical treats.

One that I encountered at Eyes, Lies & Illusions was Alfons Schilling‘s Gazelle, made in 1993. A simple artist’s portable easel incorporated a viewing device, just some hand mirrors with no lenses, pointed at a corner of the gallery (as below) piled in which was an unprepossessing array of recyclable rubbish.

What one saw through the viewer was entirely something else. Everything seen was turned upside down for a start, but most incredibly, the objects were turned inside out; that is to say, anything in the foreground now appeared in the distance, while the walls and floor somehow enwrapped everything else, as if one were peering from above into the top of a pyramid with the inside scooped out to hold illogical geometric forms that at the same time were somehow keyed to the objects on the floor in the ‘real’ world. Quite literally, it was impossible to believe your eyes!

Can this relate to photography? I have mentioned Schilling (1934–2013) before in relation to stereo photography, but his device really connects with the photo-photographic device the camera lucida. Any photographic recording, even a stereograph, of the effect of Gazelle would (no pun intended) fall flat.

Yes it is possible to get some inkling of what one sees through this device by looking at a stereo pair intended for parallel viewing with crossed eyes which will turn it ‘inside out’, but what is uncanny about Gazelle is the fact that the viewer is conscious that they are looking at real objects that are right in front of them, not a 2D picture of them; and that they are made utterly alien. Schilling’s Sehmaschinen then, might be regarded as photography as it exists between the lens and the film or sensor, or even somewhere in the viewfinder.

Schilling was already experimenting with virtual reality headsets in the early 1970s. It was his rebellious experimental spirit that drove him from the Academy of Applied Arts in Vienna, where with Günter Brus (*1938) he had paved the way for the iconoclastic Actionism movement, to Paris and New York in 1962.

Schilling’s investigation of lenticular photography added a dynamic dimension to seeing and merged several images into a single picture that could be animated with a slight shift of the head. Commonplace now, and even in the sixties they were toys, Schilling was the first to treat lenticular images seriously as a link between cinema, photography and 3D imaging.

His subsequent holograms and stereo photography, both intended to turn pictures into a virtual space, he set to new purpose.

To understand the origin and evolution of his ideas into objects like Gazelle let me summarise from an essay by Klaus Albrecht Schröder (*1955) on Schilling, Mit den Augen eines Fremden. Die Sehmaschinen (‘With the Eyes of Strangers: the Seeing Machines’) which might be read as Schilling’s manifesto:

Humankind in the industrial age has experienced a dwindling of our visual perceptive powers; a ‘lazy eye’. With each new technological innovation comes a realisation that the eye is more and more inadequate to the task of comprehension.

Scientific investigation of sight and perception informed artistic attempts to keep pace with change Helmhotz and Mach gave us the psychology of perception that was reflected in the ‘polarisation’ of reality, and radical subjectification, in the art of Monet and Degas. The perceptual shock and realisation of the permeability of the material world presented by discovery of X-Rays was accommodated in the spiritualism of Expressionism. Doubts about the ultimate reality of the visible questioned the credibility of the visual organ.

Through the 20th century increasing efficiencies in transport brought an increasing compression of space which was reflected in the use of the camera to encompass unfamilar views of the cities through tilting, aerial and ground level perspectives, cropping and which was augmented in cinema in acceleration and compression of time though editing.

However by the 1940s art had disengaged from attempting to outbid technological progress, Schröder argues. Raoul Hausmann and Siegfried Kracauer described both sociological and psychological perception as a crisis of meaning in the interwar period in resulting in increasing abstraction in parallel with more abstract social relations. Art makes us aware of the extent of our alienation from the sense of reality and it continues to work on image structures as an adaptation of the eye to change.

The artistic work of Alfons Schilling since the late 60s, may be understood in this context of a widening gulf between everyday experience and knowledge. To see his vision machines as an effort to bridge this gap is to misunderstand them; they may be prostheses, but not in a positive sense like prescription glasses; they are not telescopes and cannot do what any school microscope might.

Yet anyone who has seen for the first time with an electron microscope an apparently perfectly smooth and clean surface only to find something that looks like rubble in a quarry will understand the optical inversion apparatus of Alfons Schilling: no one can believe their eyes, nothing meets expectations nothing coincides with the decades retracted and practiced impressions and sensations.

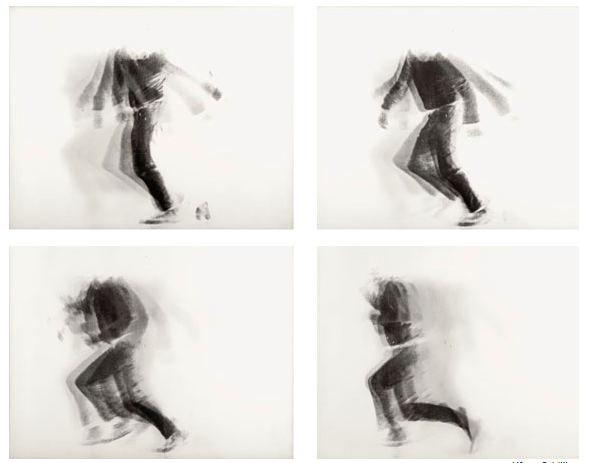

But there the similarity ends. The electron microscope makes visible something that actually exists; it is merely a question of enlargement until cracks and canyons appear in the polished tabletop, a question of distance until you encounter the world of the mites. Alfons Schilling’s devices do nothing of the kind; they do not correct, they do not expand our visual organs; they don’t enhance performance of the eye, they deny it. They refute the true perception of the eye, they are emphatically non-science. Their playfulness and ephemerality are evident records of their use in , though in the spirit of Schilling’s mischievousness we see him using them in elevated places and adjacent to great chasms.

They place us in a dreamlike world that we have never seen, and yet one we recognize at the same time.

A website has been maintained for Alfons Schilling since his death in 2013, though images provided are small and scant in number.