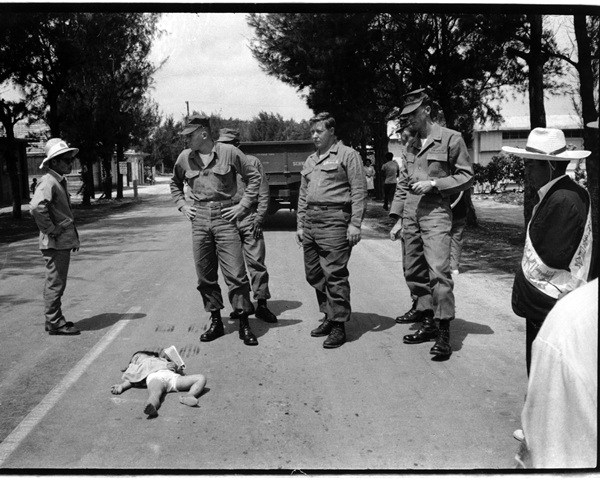

January 11: In occupied countries the clash or convergence of the native and invading cultures sometimes produces hybrid or capricious visual art.

January 11: In occupied countries the clash or convergence of the native and invading cultures sometimes produces hybrid or capricious visual art.

Ryuichi Ishikawa (*1984), who at Yamamoto Keiko Rochaix gallery at 19 Goulston St, London, E1 7TP concentrates on those on the edge of society in Okinawa, a US military base since WW2 and therefore a special case in terms of demographics and culture. According to a 2007 Okinawa Times poll, 85% of Okinawans opposed the presence of the U.S. military for the noise pollution from military drills, the risk of road and air accidents, crime, environmental degradation, and crowding from the number of personnel there.

Okinawa is the name of the Ryukyus, a chain of islands running far south of the main islands of Japan, which did not officially become part of Japan until the late 1800s. The Okinawan language and culture differ from those of the Japanese, and the ancestry of the people spans the Pacific and Southeast Asia, and since the end of World War II there have been significant calls for Okinawan/Ryukyuan independence.

zkop: a blessing in disguise is the first showing in the UK of works of Ryuichi Ishikawa, curated from his Okinawan Portraits and A Grand Polyphony series. It presents imagery of Okinawa’s alternative, underground and counter-culture society which has been the subject of a number of photographers since WW2, including the important Shomei Tomatsu (1930–2012) whose prizewinning book of photographs of Okinawa, 太陽の鉛筆, (Taiyō no enpitsu or ‘Pencil of the Sun’) was published in 1975, also Mao Ishikawa (*1953) who as a barmaid, photographed customers. Among other photographers who documented the occupied islands are Keizō Kitajima, Matumura Kumi, Yoshioka Ko, Kyudai Mineo, Makoto Arakaki, and of course, Daido Moriyama. Sequel : A Sentimental Journey: Okinawa was formative in Nobuyoshi Araki‘s career.

Ishikawa’s affection for his subjects and his optimism are in marked contrast to his predecessors and mean that his approach is more positive, though conveyed in a loaded, raw snapshot style that echoes his own words; ‘Reality is always excessive’.

Born in Okinawa in 1984, he started photography while in school before becoming a boxer. A 2006 graduate of the Department of Society and Regional Culture at Okinawa International University his period as an ‘angry young man’ reflected in his photography of the period was tempered by his study of avant-garde dance with Seiryu Shiba in 2008. He then continued his photography studies with Tetsushi Yuzaki in 2010, and at the 3rd Shomei Digital Photography Workshop he won the 2014 Kimura Ihei Photography Award.

Last year he curated a show at the Okinawa Prefecture Art Museum. He wanted to express the current mood in Okinawa and didn’t think the U.S military bases and reversion to Japanese rule (2006 and ongoing) were issues relevant to the show, but in a 2017 interview with Daryl Mitchell and Naoko Uchima of Cotonoha journal, he admitted that he was forced to realise that most Okinawan photography is political;

There is a cultural battle between Okinawa and Japan. Society in Okinawa, as a whole, is involved in this struggle, and so are local artists. However, each generation of artists deals with this differently…young artists know little about the Battle of Okinawa and Okinawa’s reversion to Japanese rule. In stark contrast to artists who are now in their 60’s, they don’t share a unified historical narrative; thus, these artists feel that they are individuals in society, while artists who are now in their 60’s feel they are members of society.

Okinawa is the poorest prefecture in Japan and that is reflected in many of Ishikawa’s portraits, street photographs and urban imagery.

Raymond Voinquel, born on this date in 1912 (†1994), would have been unlikely to approve of Ryuichi Ishikawa’s approach, though he is these days largely forgotten. He came to Paris from Fraize, Vosges, on the mountainous border with Germany, in 1927 to work as an errand-boy at La Coupole. There his passion for drawing and painting attracted actors and inspired their sympathy. He was then a Mistinguett boy, accompanying the famously cantankerous showgirl in revues, before taking up photography in 1930 as assistant to Roger Forster (1902–1984) as a stills photographer and as a fashion photographer on the side.

After WW1, with his experience of stills, he entered the famous photography studio founded in 1934 by Cosette Harcourt (pseudonym of Germaine Hirschfeld 1900–1976) who influenced him, and where, for half a century, he employed elaborate lighting and extreme editing to immortalize the stars of around 160 films. Unlike Ryuichi Ishikawa, Voinquel disdained the accidental, the snapshot; “My most beautiful pictures are the ones I posed,” he said.

During WW2 Voinquel was no Resistance hero; his work accelerated during the Nazi Occupation and it was from 1940 to 1944 that he became particularly interested in photographing the male nude;

I did well out of the Germans. Perhaps 40 a day came into my studio to have their portrait taken. I’ve no idea what the pictures were for – probably to send home to Germany.

He never drew the Nazi attentions that dogged Robert Doisneau or Henri Cartier-Bresson;

I don’t get mixed up in politics, I’ve a horror of it. That ends up in the concentration camps.

In fact the film industry in which he worked benefitted from Vichy rule. Production continued, especially with the German ban on British and American films and attendances increased as crowds sought the warmth of cinemas.

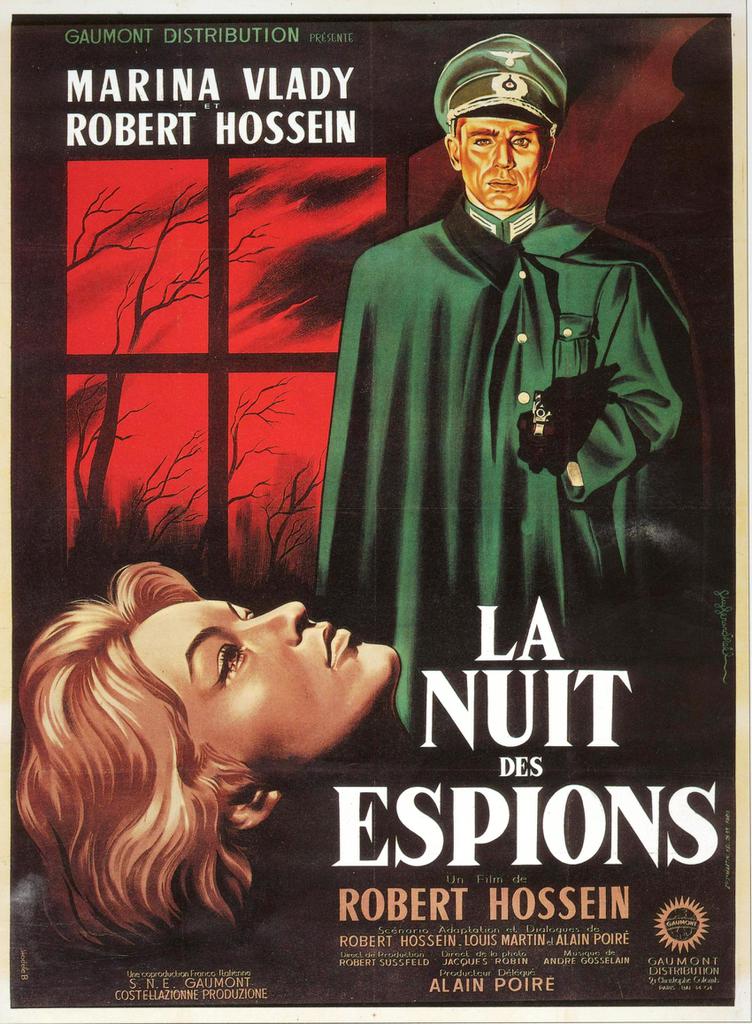

In particular the company Continental, created in September 1940 by the Nazi Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels to help suppress French nationalism, benefitted from finance and management by the Germans. Under the direction of former soldier and staunch Nazi, Alfred Greven it produced thirty films between 1941 and 1944.

Surveys of the films produced at this time see an increase in films with strong female leads catering to a female audience, though also to a fascist ideology, as they promote domesticity and motherhood.

The escape into fantasy is also apparent in the magical and legendary subjects of Carné’s Les Visiteurs du soir about the devil visiting a mediaeval court (banned by the Germans), and Cocteau’s L’Eternal Retour (1943) directed by Jean Delannoy which was a reworking of Tristan and Isolde, and both directors Marcel Carné and Jean Cocteau count amongst Voinquel’s clients, along with Max Ophüls, Jean Renoir, Sacha Guitry, Jean-Pierre Melville, Henri Decoin, Yves Allegrét, Luis Buñuel and later Alfred Hitchcock.

His career in making film stills spanned the years 1931 to 1977, but his nude photography began in 1940, in a project to illustrate Paul Valéry‘s poem Narcisse.

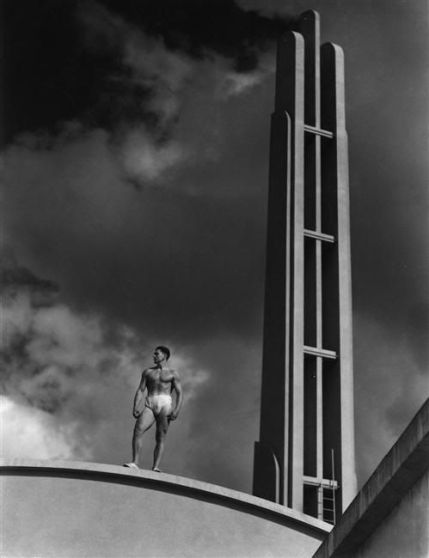

When in 1941 he photographed athletes at the stadium in Bordeaux, he used extreme angles of view against backdrops of architecture and skies for aggressively muscular imagery that may be seen to carry more than a little of the fascist ethos.

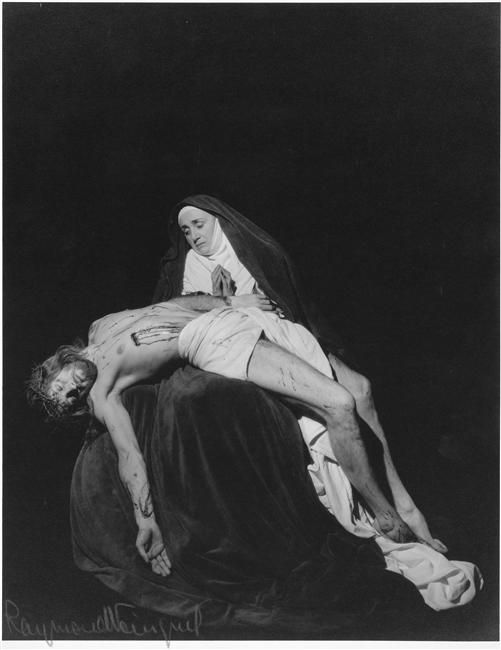

Actors Louis Jourdan et Jean Marais posed nude for him in imagery that he intended as homage to Michelangelo and Caravaggio.

He is a master of camp but also a perfectionist; that is to say he employs an overheated theatricality, often cinematic in an early mid-century Hollywood style, to a point that borders on the kitsch, though his lighting and framing are highly polished.

Backlighting, carefully positioned spots, shaped lights and shadows, washes over drapes and cloth, dazzling specular reflections, vignettes, and shifts of focus, as well as his preference for a black-painted studio or set which would soak up all bounce-light; these ingredients contribute to a fantasia of painting, cinema and photography. And of course the resulting images are camp in being homoerotic (though not pornographic) but his treatment for the male nude and the (usually clothed) female film star is the same.

Above, his montaged shot of Jean Marais combines a close-up of fernery with a mannerist tilt that precariously perches the figure on a slope like that of Michaelangelo’s Medici Tomb, and amidst all the drama, we barely register that the window frames behind Edwige Feuillere are mere props that hang unattached to any architecture.

The mid-century film stills photographer fulfilled the roles of recording mundane production shots as part of continuity, as well as making publicity images distributed to the media, provided to poster artists or displayed as 8×10 prints in the foyer as a static preview of the screenplay. However Voinquel was the only one amongst those in Harcourt’s studio to sign his prints.

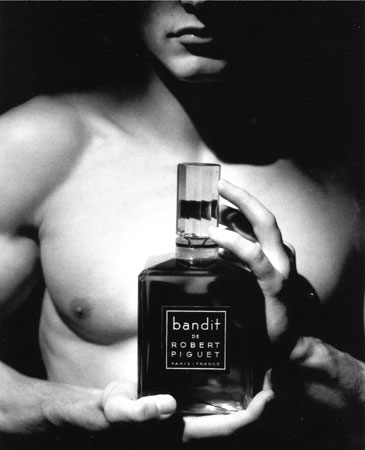

At heart, Voinquel’s interests are commercial and he turns his love of the male physique to that purpose in numbers of advertising images which were another very successful facet of his practice.

The nadir of Voinquel’s artistry is his tribute to Jean Cocteau whom he had often photographed, most successfully in one of his most simply lit but most noir portraits (left, below) in which he appears to emerge from a filigree cast-iron screen. He said of Cocteau that he was a visionary who “saw the light before everyone else”.

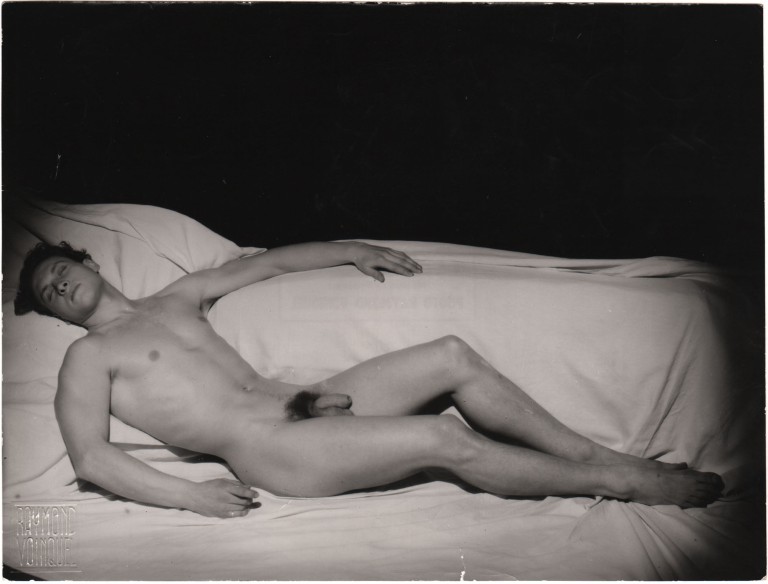

When the writer, designer, playwright, artist and filmmaker died in 1963, Voinquel released a photograph of Cocteau lying in state, fulfilling his pre-arranged commission.

In its lighting it recalls the background of the portrait in its closed shutters; is it daylight or moonlight that stripes them? Perhaps, following a common practice on movie sets where in order to maintain consistency in the lighting, the windows may be screened off from daylight and specially lit. The curtains are parted theatrically above Cocteau’s pillowed head where he rests in death. The electric candles still glimmer feebly.

To illuminate the corpse, Raymond Voinquel substitutes ambient and indirect lighting with two spotlights; one at the right corner is softened slightly by a gobo of crumpled paper, and a direct light that is held at arm’s length by a young man. His handsome face, tousled black hair and dark suit are lit by a shuttered spot out of shot to right of camera which also picks out the long shaft of the candle in front of him. The scene is more film noir than mortuary and attention falls more on the young man who stands like a resurrection of the deceased poet

Voinquel, the showman, recruits Eros to portray Thanatos, the director of the Beauty and the Beast and The Poet’s Blood, whose motto was “Cinema is filming death at work.”

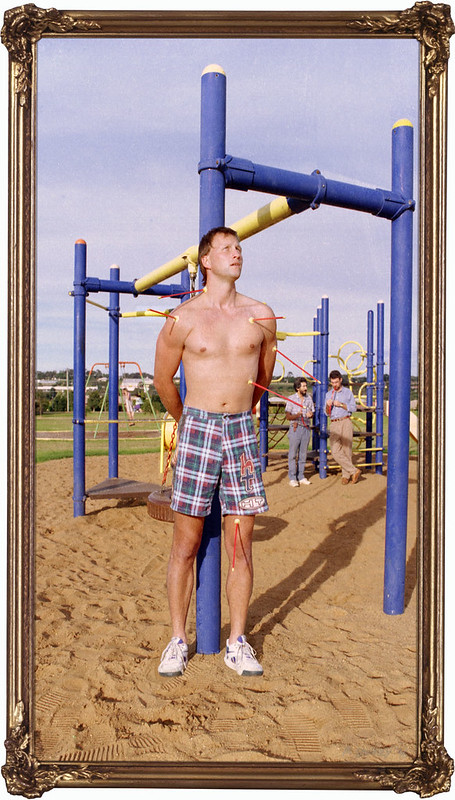

Voinquel’s work lives on in the inspiration that the duo Pierre et Gilles (Pierre Commoy *1950 and Gilles Blanchard *1953) drew from his nautically themed fantasies, notably of the comedian Louis Jourdan, for their Les Naufrages (The Wrecks), a 1986 series that depicts the beauty of shipwrecked sailors’ bodies intertwined in nets and fishing ropes. Like Voinquel, Pierre et Gilles bespangle the beauty of the masculine body, and like him, though theirs are more discreet, they produce glorious treatments of the iconography of the Christian martyrs.

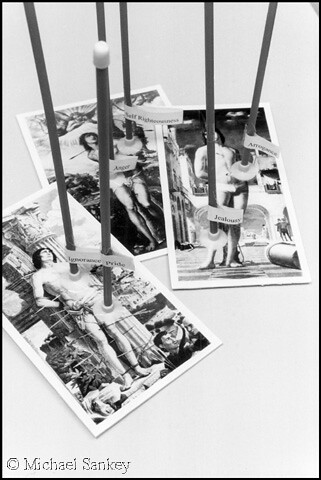

And another 2 St Sebastian’s for you – or at least their thumbnails 🙂

LikeLike

Thank you…I do enjoy the playground version Mike…is it yours?

LikeLike

Yes both mine James. From a solo exhibition called Differing Views back in 1996, where I was exploring appropriation of iconic imagery using, then, new digital techniques. See: https://www.flickr.com/photos/62191340@N07/sets/72157632409055806/

LikeLiked by 1 person