What does colour add to a photograph?

What does colour add to a photograph?

This blog runs on a calendric roulette, its content dictated by which photographers had been born or died on that date in history, what pictures were published on that day, exhibitions opened, discoveries or inventions announced, in the world of photography. It’s exciting to discover in this serendipitous manner aspects and instances of the medium I love.

So it is that we encounter Marcus Selmer, a Dane born on this date in 1819 in Randers and who died on January 18, 1900 in Bergen, the town he adopted in Norway, its first permanently established photographer in 1852. The Bergen bourgeoisie flocked to his studio; he was the city’s premier photographer and continued to trade until his death in 1900.

He began photographing with the daguerreotype in 1854 but kept up with international developments in the medium, adapting to wet plate and dry plate technologies. He became known for his landscapes and views, and a year after he came to Norway he began to take pictures of national costumes.

Where others collected traditional music, dance, and folk tales and painted what was typical of recently liberated Norway, Selmer created these studies of national costumes, pictures bought by Norwegians and tourists alike and used by 1860s painter Adolph Tidemand for several of his larger compositions. Selmer’s costume pictures were published in 1872 as A Catalogue of Photographs of Norwegian National Costumes, Landscapes, and Stereoscope Pictures From Nature taken by M. Selmer in Bergen.

Unfortunately his entire negative archive was destroyed on his death, but many of his ethnographic photographs survive, many found in the collections of Norway’s Preus Museum (Norwegian Museum of Photography), National Library, the University Library in Bergen, the Norwegian Folk Museum, Old Bergen Museum, and the Biblioteque National de France, because of the numbers of these images sold to locals and tourists for whom they became mementos of an almost mediaeval country of numerous separate cultures existing in isolation because of the extreme geographic and climatic conditions. Those costume photographs came to influence the Norwegian self-image of nature and folk life.

Selmer’s pictures emphasise costume especially when hand-coloured, as numbers were, and because of his waist-level viewpoint, the camera position later adopted as optimum by modern fashion photographers. The traces of a mass-production hand colouring process can be seen in this portrait of a groom from Karasjok in Nordland dressed in his finery; a long leather jacket and red fur hat against painted backdrop with mountain motif. It’s an 8×10 inch salt paper print and the red paint is the sole colour used, daubed on for the hat and trim, tinting the belt buckle and dilute for the supposedly evening sky. A detail of the collar, not clear in the white on white of the original, has been inked in.

Another of his images is more convincingly coloured in four colours; violet, red, yellow and blue. Here is a woman from Slidre in Valdres playing a langeleik (a zither-like instrument), and simultaneously tugging on the string of a dancing puppet.

Another of his images is more convincingly coloured in four colours; violet, red, yellow and blue. Here is a woman from Slidre in Valdres playing a langeleik (a zither-like instrument), and simultaneously tugging on the string of a dancing puppet.

In rare instance of a photograph on location, Selmer pictures this ‘street girl’ who appears to be gutting fish. This image is smaller, in carte-de-visite format, very sparsely coloured and, shot from shoulder height, becomes much more about the subject and her situation, a poverty-stricken casual worker perhaps employed to gut and salt fish, than a ‘folk dress’ record, though its ethnographic value remains.

Items on BuzzFeed, Twitter, Instagram and Facebook appear regularly with the usual inappropriate hyperbole – ‘incredible’, ‘amazing’…

…but rarely mentioned are either the period when the original photos were taken (1904-1920), nor the photographer’s name; chief registry clerk Augustus Francis Sherman (1865-1925), about whom very little is known, though he was evidently a remarkably capable photographer as can be see in his picture of a Romanian piper. Here are Sherman’s monochrome version and the much-hyped digitally coloured version…

…but rarely mentioned are either the period when the original photos were taken (1904-1920), nor the photographer’s name; chief registry clerk Augustus Francis Sherman (1865-1925), about whom very little is known, though he was evidently a remarkably capable photographer as can be see in his picture of a Romanian piper. Here are Sherman’s monochrome version and the much-hyped digitally coloured version…

An amateur, his employment gave him special access to potential subjects amongst the immigrants housed at Ellis Island for his camera. It is possible, for example, that Commissioner Williams requested that he photograph specific individuals and groups, and likely that Sherman persuaded subjects who were waiting for what they needed to leave the island (an escort, or money, or travel tickets), to pose in their national dress, which they had brought with them.

Published in National Geographic in 1907 Sherman’s pictures for decades hung anonymously in the lower Manhattan headquarters of the federal Immigration Service, and given by the Commissioner to official Ellis Island visitors as mementoes.

The digital colourisers of Sherman’s (and others’) pictures are Dynamichrome who have contributed their services to a crowdfunded book called The Paper Time Machine, by Wolfgang Wilding and Jordan Lloyd, just published by Penguin, which is hyped as “a book that will change the way you think about the past.”

Mainstream media reports echo the hype, and a phrase often used, which piques my interest, is that the images have been ‘brought to life’ by being digitally ‘hand-coloured’. As the director of Dynamichrome Jordan Lloyd admits;

The craft of adding color to black and white photographs has been around as long as the medium of photography.

But as they distinguish their approach from what is now a widespread trend amongst amateur photographers…

Digital Color Reconstruction is its latest incarnation, combining historical investigation and technology to create an authentic representation of an existing record.

Another Ellis island photographer has had his images digitally coloured by Sanna Dullaway earlier for TIME magazine; Lewis Hine also photographed there and I believe his images of child labour are cheapened by the process, though the public reaction has been just as enthusiastic as it is now for Sherman.

Are people so used to seeing colour photographs that they are incapable of imagining that the subjects of historical images are real people like them without seeing them in colour? I suspect so, but the photographer used to working in monochrome makes compensation, as they shoot, for the way they intend the final image to look in black and white, and will work differently if the image is to be in colour.

Ansel Adams called this way of photographing previsualisation. A hand-coloured Ansel Adams would be regarded as sacrilege…an abomination! Likewise, artists make monochrome drawings, not because they don’t have paint available, but because drawings serve a different purpose to a painting and the lack of colour enhances the attention they can pay to linear effect or to light and shade.

Perhaps Sherman, as Selmer certainly did, intended his photographs to be hand-coloured. Here is his version of the piper prepared as a magic lantern slide, coloured on the reverse (the side you are looking at).

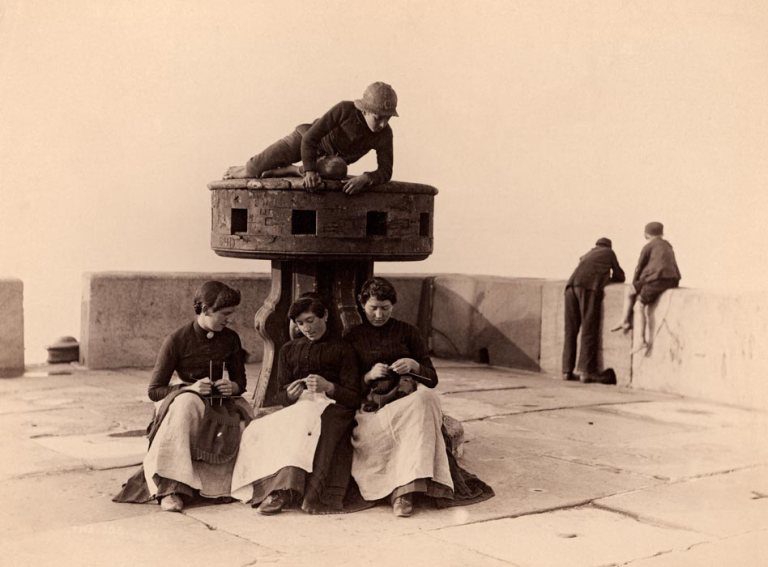

Also born on this date, in 1853, was British photographer Frank Meadow Sutcliffe (†1941) who operated a studio for over forty-five years in Whitby, Yorkshire. His portrait business was seasonal, so he became an early street photographer of children, fishermen, and merchants, going about their daily routines, compensating for equipment more cumbersome that that later used by Cartier-Bresson or Winogrand by exploiting the way people posed naturally in realistic settings.

His prints were in carbon, the tinted tones of which enhance the monochrome qualities of his imagery. It is his use of the environment of his subjects and interactions between subjects that make his photographs more valuable anthropologically, their visual information not restricted to dress. Given that these people adopt such believable attitudes and appear to ignore the intrusion of the camera, are Sutcliffe’s images sufficiently ‘naturalistic’ without the addition of colour? What would ‘colourising’ them add?

This was llovely to read

LikeLike