September 6: Spying though a keyhole is a commonplace metaphor, but applied to photography is apt nevertheless.

September 6: Spying though a keyhole is a commonplace metaphor, but applied to photography is apt nevertheless.

Guided to the keyhole by delinquent curiosity, in peering through we are left unsatisfied by the mere glimpse, our line of sight locked straight ahead.

The photograph, or at least the lens and the sensibility that guided it, are similarly constrained, and our inquisitiveness frustrated. Two photographers born on this date peer through keyholes with opposite political intent.

Lambertus Jasper (Bart) de Kok was born on this date at Nijmegen in 1896 (†1972) and in 1925 set up business as a technical photographer. Prior to and during the Second World War he was a member of the fascist Dutch organisation Nationaal-Socialistische Beweging in Nederland (NSB), active 1931-1945, which developed in imitation of Nazism and Italian rightist movements, typified by its cry ‘Hou-Zee’ as the equivalent of ‘Seig-Heil’.

De Kok, thus more committed than the sanguine opportunist some take him to be, became an agent provocateur reporting on resistance meetings at Suisse Hotel or the Brouwerswapen café to Joseph Hoosemans who worked for the Sicherheitsdienst (SD, the occupation police). Eventually, De Kok passed the names of more than twenty people to the SD.

Sometime in 1941 he befriended the anti-semite saboteur and propagandist Van Poppel who introduced Bart de Kok to the Press Commissioner, Boijes. Boijes ordered De Kok to take pictures of ‘all the political events’: activities of the WA (the NSB’s violent vigilantes) and of riots between WAs and members of the Dutch Union.

De Kok was commissioned by the German occupying forces and the Amsterdam detective Willem Klarenbeek to photograph their activities forbidden to other photographers. Where members of the resistance group De Ondergedoken Camera (The Underground Camera) made their pictures of the Occupation clandestinely, he was able to use his camera openly.

Photos he made in 1943 at the Muiderpoort station of transport of Jews to concentration camps were published during the war, along with shots of illegal kosher slaughterhouses which were printed alongside anti-semitic comments, and of a raid by the CCD of Wolf Hartlooper café.

Subjects of some appear trivial now, such as the removal of Jewish street names, and international signage on a hairdresser’s shop (though of the use of English was forbidden and his shots may have been used to harass the owner).

When supplying his pictures to the Germans, De Kok secretly made a second print of each photo and kept it in the house of Joseph van Poppel, in Amsterdam South.

Van Poppel had started his work for the Germans with the recruitment of men for Abwehr intelligence gathering and sabotage, then in 1942 Van Poppel in Belgium befriended Helena Lam who was Jewish. Using her house, Van Poppel won the trust of Dutch Jews who wanted to escape to England, Switzerland or Portugal, but who instead found themselves betrayed; imprisoned or transported to concentration camps.

After the war De Kok and Van Poppel were tried, fined and briefly imprisoned for their activities, but a search of the house failed to find any of the pictures.

- Bart De Kok (1941) Sicherheitsdienst raid on a Jewish restaurant.

In 2010, a renovation of a house in Amsterdam South discovered 250 of De Koks’ photographs, which he made in 1941 and 1942. These photographs show a confrontation during the February Strike by workers against the German occupiers in response to persecution and deportations of Jewish workers, which was brutally repressed. A major corpus is De Kok’s documentation of the seizure of diamonds from the mostly Jewish traders at the Diamond Fair on April 17, 1942.

De Kok’s prying photographs convey only fragments of the overall story, frequently poorly composed or ill-timed, and often cryptic, with references that can be understood only from a collaborator’s perspective. That he kept, or at least did not destroy, his copies is strange as they ultimately they are self-incriminating.

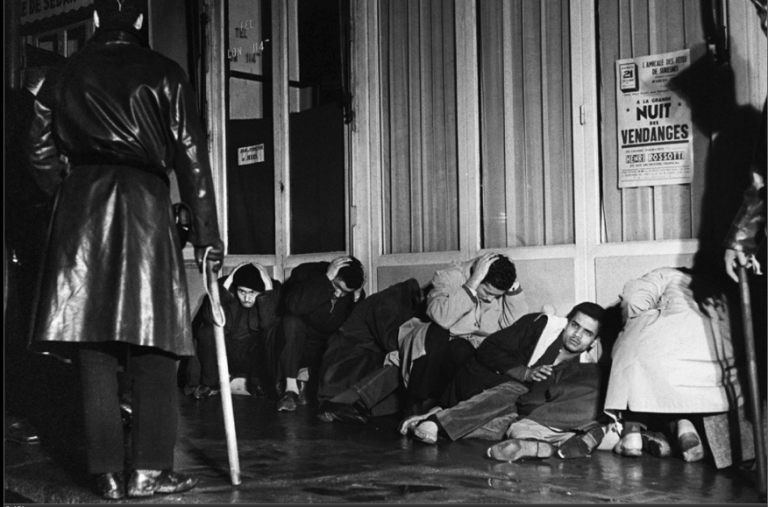

Also born on this date, in 1934, is Georges Azenstarck who on witnessed in Paris the violent response by the police to a peaceful demonstration organized by Algerian workers and supporters of FLN (the Algerian National Liberation Front) against the imposition of a curfew that limited circulation in the city and prevented workers from getting to night-shifts at various factories.

Azenstarck, then a staff photographer at the Communist newspaper L’Humanité, was on assignment at the time: “J’étais là. Je l’ai vu devant moi.”

Shooting from the newspaper’s balcony, opposite the cinema Rex on the Grands Boulevards, he photographed police repression.

His photos were published only years later and are still difficult to track down though they will be seen, transcribed as photorealist renderings in an exhibition Service Special, by the French artist Eric Manigaud at Charlie Smith London gallery 336 Old Street, 2nd Floor, London EC1V 9DR, opening in two days and running until 07 October 2017.

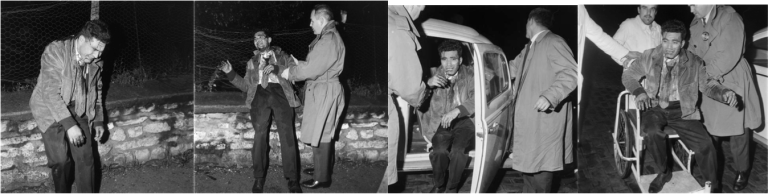

Azenstarck was one of only a few photographers to document the events of October 17, 1961 in Paris, but it was Élie Kagan (1928–1999) who was in the midst of the action, quickly moving with it on his Vespa to the various sites of violence with his 6×6 camera and flash.

- In Nanterre, Kagan and an American journalist take a wounded man to the Nanterre Hospital. Kagan knew nothing more of this man, but he has been identified as Abdelkader Bennehar thanks to the testimony of his nephew in Oran in 2000 thanks to the publication of Jean-Luc Einaudi’s La Bataille de Paris which featured Kagan’s pictures of Kagan. Bennehar died of multiple fractures of the skull under obscure conditions after his arrival in the hospital.

France in October 1961 was mired in the Algerian War. With negotiations at a standstill the National Liberation Front in Algeria broke the truce and conducted attacks and bombings against the law enforcement agency. This gave Paris Police Chief Maurice Papon, a former collaborator with the WW2 German occupiers and the very man who led the repression in Algeria in 1945, the excuse to impose the curfew in Paris.

It wasn’t until 1981 that evidence of his collaboration emerged: his signature was uncovered on papers ordering the deportation of over 1,600 French Jews to Drancy internment camp, subsequently to be exterminated, though it wasn’t until 1997 that Papon was finally put on trial in 1997 and convicted the following year of crimes against humanity. On October 5 he ordered the curfew for so-called FMA (French Muslims of Algeria).

By late afternoon of October 17 about 30,000-50,000 Algerians responded to the FLN agitation and start arriving from the suburbs for three gathering points: west (Etoile), south (Boulevard Saint Michel and boulevard Saint Germain); and east (the area of the Grands Boulevards).

By late afternoon of October 17 about 30,000-50,000 Algerians responded to the FLN agitation and start arriving from the suburbs for three gathering points: west (Etoile), south (Boulevard Saint Michel and boulevard Saint Germain); and east (the area of the Grands Boulevards).

They conducted a completely peaceful demonstration accompanied by women and children. Weapons were expressly forbidden and this was enforced by the organisers.

They conducted a completely peaceful demonstration accompanied by women and children. Weapons were expressly forbidden and this was enforced by the organisers.

Because the prefecture had prepared for the management of little more than 1,600 men, their forces were insufficient and that contributed to the unreasonable repressive response which blocked the processions west of Pont de Neuilly, in the south up to Pont Saint-Michel and east to the Place de la République, places where the violence was most severe.

Historian Jean-Luc Einaudi (1951–2014) has, despite the long-term official cover-up, compiled evidence, including photographs, of a tally of at least 200 dead, all Algerians, with 2,000 wounded.

The official version, on October 18, admitted the death of only three, though in the following days, papers reported bodies in the Seine and others were found, some hanged, in the woods of Boulogne and Vincennes; the police had tried to hide the evidence by washing the streets with water cannons, throwing bodies into the river or leaving them in the woods outside the capital.

The massacre did not end that night. Thousands of people (according to the study of some of the police documents, there were about 12,500) were detained on the wagons and deported to detention centres scattered throughout Paris and remained there several days undergoing torture and violence, with over 2,000 people still detained in a centre in Vincennes by October 26.

Since the trial of Papon in which Jean-Luc Einaudi’s important and controversial book, La bataille de Paris: 17 octobre 1961 (1991) played an important part, and after the appearance of Faïza Guene‘s documentary with Bernard Richard Memoires du 17 octobre (2002), the massacre has been given more attention, though facts are still disputed by right-wing groups, especially in context of the forced migration by seekers of asylum from northern Africa.

These photographers, from opposing political convictions, present us with often sparsely contextualised imagery into wider, complex social upheaval as a consequence of the technical constraints of the medium.

2 thoughts on “September 6: Keyhole”