January 9: Annemarie Heinrich was born on this date in 1912 in Germany, but from her photographs one can imagine her only as an Argentine, which is where she was moved as a child 1926 when she was twelve years old by her father, a concert violinist and socialist who feared another war in Europe.

January 9: Annemarie Heinrich was born on this date in 1912 in Germany, but from her photographs one can imagine her only as an Argentine, which is where she was moved as a child 1926 when she was twelve years old by her father, a concert violinist and socialist who feared another war in Europe.

The world she left behind in Germany was actually more permissive than her adopted Catholic country of Argentina, but the passion of her photography is Latin, if we dare perpetuate the cliché. In fact Argentina was undergoing a Catholic revival and a shift of power toward the Church and the Army which was to prove revolutionary, leading to an era in which the strong-arm government of Juan Domingo Peron was strongly supported by the country’s institutional Catholicism.

She was taught by her uncle who was a photographer in the town of Entre Ríos, and set up her own darkroom at home. In 1930 when she opened her first studio in Buenos Aires she was eighteen years old. She had to pawn her camera to have enough money for chemistry, eventually made enough money to buy a large-format camera, and produced work for ‘gossip’ magazines El Hogar, Sintonía, and Alta Sociedad. At the same time she began her career as a portraitist of great figures of the Teatro Colon. For forty years straight she illustrated the covers of the magazines Antena and Radiolandia.

In the 40s, her portraits of the stars of Argentine cinema, such as Tita Merello, Carmen Miranda, Zully Moreno and Mirtha Legrand, and also Eva Duarte (later Perón) were her specialty.

As Juan Travnik writes in Una cuerpo, una luz, un reflejo (Ediciones Larivière, 2015);

Annemarie Heinrich became the creator of a genre which in Argentina, as well as in other countries, developed side by side with the growth of the film industry and the popularization of the radio.

Heinrich photographed the celebrities in the style of the contemporaneous Hollywood portraitist George Hurrell. Her technique enhanced the beauty of the sitter. She orchestrated a complex lighting set-up of spotlights directed over the sitter to create harsh, dramatic lighting with strong shadows that could sculpt the facial features instead of flattening them. She worked on large formats of 5×7 or 6×8 which permitted retouching of the negatives, using graphite pencil on the emulsion side to fill low density areas of the emulsion to eliminate facial imperfections, such as wrinkles and blemishes, to lighten eyes, to smooth skin textures and augment the sensual fullness of lips. “Surely I will not go to heaven because for most of my career I constantly used retouching and I did not keep track of the number of fat women I portrayed as skinny,” she confessed.

A comparison of her covers of Radiolandia (above), one from the forties and the other of the seventies, reveals how much more comfortable she was with the hand-coloured monochrome, dramatically-lit image-making of mid-century than she was with the flattening effect of the ‘soft-box’ lighting in vogue in the 1970s and early colour negative films, which in her hands produces a rather bland effect.

Because of its repression under a Catholic-sanctioned military rule, twentieth-century cinema of Argentina is typified by melodramas featuring long-suffering heroines, but this genre paradoxically incorporated significant, and perhaps consciously subversive, imagery and narratives of female rebellion in what was an early impulse of liberation.

There is an element of subversion in Heinrich’s image-making for cinema publicity that underlines her own feminist attitudes. Her photograph of the actress Ana Maria Lynch as La Quintrala, an historical seventeenth-century Chilean noblewoman who killed her lover as part of a scheme to seduce a priest in Hugo del Carril’s film of that name.

Lynch is presented as an imperious seducer dressed totally in a black suggestive of the black widow spider. Hard light from top left sculpts the lips and glistens in the bold and coldly staring eyes. With heavy and elaborate earrings the character commands social and economic power as well as sexual. A broad floodlight is added directly behind the actor’s head to give her a halo which accentuates the crown-like black headdress and veil. In contrast however to the haloed Virgin, who is conventionally represented with demurely averted eyes, is Lynch’s chillingly defiant stare.

As La Quintrala’s sin was to seduce a priest invested with Holy Orders, and as a consequence brings about his execution by public hanging, Heinrich’s addition of the halo would appear to be a deliberate desecration the conventions of Catholic iconography; daring in the height of the era of Juan Domingo Peron’s institutionalisation of Catholic rule. Such a stance by Heinrich is consistent with her anti-war agitations in the 1940s.

Heinrich was well recognised for her professional achievements; among the many other professional distinctions she achieved included membership of the Argentine Council of Photography, and election as director of the Association of Professional Photographers. She was a member of the Federación Argentina de Fotografía and Photo Club Buenos Aires, and Honorable Executive of the Federation Internationale de l’Art Photographique.

Heinrich pioneered photography as art in Argentina; she was founder and only female member of the short-lived association of photographers Carpeta de los Diez and her first solo exhibition was in Chile 1938 and from then she held numerous exhibitions in Argentina and abroad.

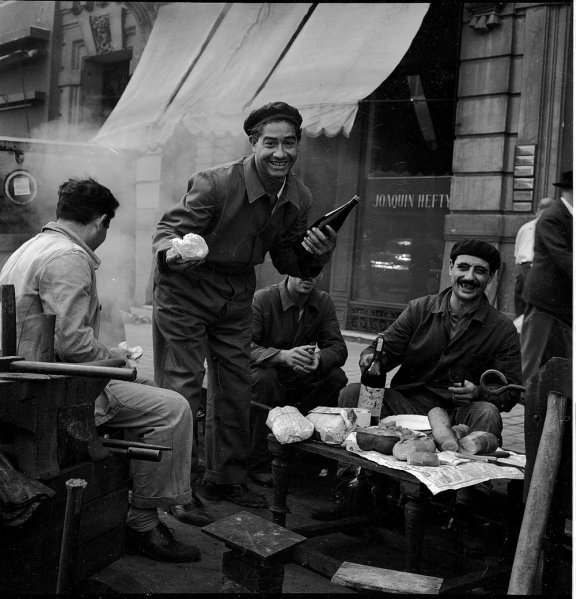

Annemarie Heinrich’s drive to make her way as a woman in photography can be read in her personal photography which she was carrying on in the background of her more commercial production. Many of her private photographs are from her travels in Argentina, Latin America and Europe between the 1930s and 1950s. Annmarie treasured these images but rarely exhibited any of them as she considered the public to be more interested in her portfolio of portrait work for which she was renowned.

These private images surfaced at the landmark exhibition Annemarie Heinrich: Secret Intentions in 2015 at the Museum of Latin American Art of Buenos Aires (MALBA), Avenue President Figueroa, Buenos Aires, prompting an assessment of this assertive, passionate photographer as a photo-feminist.

Heinrich had an avant-garde approach to the body and to female sexuality and sensuality, and her attitude to men may be summed up in these two images expressing a triumph of Eve over a diminished Adam; an attitude no doubt annealed in her professional encounters!

Heinrich’s Desnudos (Nudes), which she began as early as 1934, stand as unique in the representation of the female body by a female photographer. She kept her nude studies private after her 1946 explicit nudes of fellow German immigrant and actress, the ‘Argentine Atomic Bomb’, Tilda Thamar caused a scandal. Thamar at the time was controversial already for her films Le pijama de Adán (1942), in which she appears very scantily clad, and in bikinis in Adán y la serpiente (1946).

Working with friends as models, Heinrich permits herself the freedom of experimenting with lighting, movement and double exposure. The striking difference between these images of women and her pubiciy photographs is that the models are relaxed, luxuriating in their own physicality (rather than than the overt sexuality that we see in the Carmen Miranda shots above) and the neutrality of their interaction with a photographer who is female.

There is an intimacy here, but something else is intended that becomes especially apparent when these poses are compared with Heinrich’s 1969 Summer in the City. Here, a young woman basks in the sun high on a chimney high above the concrete jungle of Buenos Aries. We can see the ladder she has climbed to get to her private eyrie where she is all alone, untroubled by the clamour and clutter of the city. With her book and one abandoned shoe beside her, the legs of her jeans rolled casually, she drowses in the sun. There is both abandon and defiance in this pose which is directed by the photographer, and she might as well be naked as clothed. Look back at the nudes and this is their expression; a liberation complete.

Are we to see them as a reflection of herself?

Her self-portraits are another category of her work, like her portraits of artists and writers such as Jorge Luis Borges, which there is little space left to discuss here. Any self-portrait gives us insight into the photographer in a way that their other images cannot. Heinrich sums up her professional career in this image with her signature projected across prints of her many celebrity portraits… …but this innovative use of the mirror, so commonly used in self-portraits is un-common, and intriguing…the camera (we) looks over Heinrich’s shoulder at her reflection in mirror, large enough to encompass her whole figure, the rough edge of which slices the right side of the print. That mirror is itself reflected in the chrome globe on the plinth next to her. There are three Annamaries here, each watching the others, and not us, critically, piercingly, while the camera looks on with its hungry, glinting eye. We become unseen observers of an unsettling picture, but one in which Heinrich exerts her directorial control. his is indeed reveals the Strategies of the Gaze!

…but this innovative use of the mirror, so commonly used in self-portraits is un-common, and intriguing…the camera (we) looks over Heinrich’s shoulder at her reflection in mirror, large enough to encompass her whole figure, the rough edge of which slices the right side of the print. That mirror is itself reflected in the chrome globe on the plinth next to her. There are three Annamaries here, each watching the others, and not us, critically, piercingly, while the camera looks on with its hungry, glinting eye. We become unseen observers of an unsettling picture, but one in which Heinrich exerts her directorial control. his is indeed reveals the Strategies of the Gaze!

Heinrich lived and worked on in Buenos Aires until her death in 2005, leaving her children Alicia and Ricardo Sanguinetti, who are also photographers, and her husband Alvaro Sol (writer Ricardo Sanguinetti) whom she had married in 1939, becoming an Argentine citizen.

Her family appears in others of these self-portraits in which the chrome ball becomes a plaything here…

…while this self-portrait with her two children is a more sombre revelation of her domestic life. Her son Ricardo looms over his mother at the top of the ball while daughter Alicia adopts a balletic pose on the polished boards of the floor. The spot also used to light the mirror self-portrait above is seen on the right and along the wall is another, with two floods on a stand above a classical bust next to a portrait camera on a stand used for the shot above. On the rear wall is the mural of cavorting horses, which appears as the backdrop to the dancing nude above.

Her work is gaining worldwide attention particularly since it was shown in New York for the first time in 2016 at Nailya Alexander Gallery in the show Annemarie Heinrich: Glamour and Modernity in Buenos Aires.