November 26: We tend to regard appropriation in photography as a postmodern phenomenon, but of course one has only to think of Julia Margaret Cameron (1815–1879) to conjure images of her servant Mary Hillier as Raphaelesque Madonna to realise that the impulse to imitate, or directly copy, artworks in other media is as old as photography itself.

November 26: We tend to regard appropriation in photography as a postmodern phenomenon, but of course one has only to think of Julia Margaret Cameron (1815–1879) to conjure images of her servant Mary Hillier as Raphaelesque Madonna to realise that the impulse to imitate, or directly copy, artworks in other media is as old as photography itself.

To consider the camera obscura and the camera lucida and their uses in painting and we don’t need Walter Benjamin to explain to us what impact mechanical – read lens-based -technology has had.

Some of the first lensed images preserved by the medium in its infancy were the engravings copied by Niecephore Niepce.

The tableau vivant, literally a living painting, is a parlour game or public display using live models in costume. It was easily adapted to early photography as an ideal manner of artistic picture-making well suited to the slow exposures and cumbersome equipment of the medium in this period.

It is described at length by Mrs Severn in The Lady Companion; or, Sketches of Life, Manners, and Morals, at the Present Day (1854) who defines tableau vivant:

its real purpose is to arrange scientifically a combination of natural objects, so as to make a good picture, according to the rules of art.

A tableau vivant is literally what its name imports— a living picture composed of living persons; and, when skilfully arranged and seen at a proper distance, it produces all the effect of a real picture.

Severn goes on to describe at length the various tricks that might be employed to make a convincing tableau vivant, including the use of strategically placed lights, cleverly shaded to project shadows of the original painting, posing the performance in a doorway to form a frame and keep distance from the audience that would duplicate painterly perspective, and the use of gauzes, black or white stretched over the doorframe in imitation of canvas texture and to blur mundane detail.

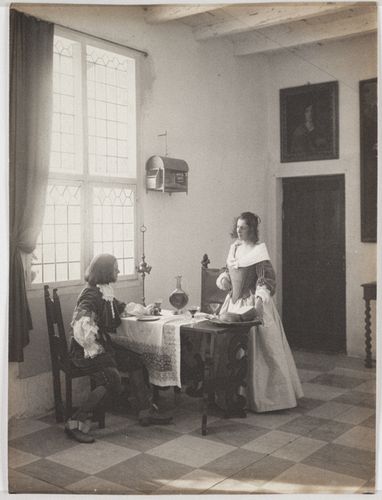

Today, in 1861, is the birthdate of Guido Rey, a man wealthy enough to pursue photography at leisure and to travel, made this series of tableaux based closely on paintings by Vermeer and de Hooch. Using props appropriate to the period of the Dutch ‘Golden Age’ from his own possessions and borrowed from friends, he constructed scenes that nevertheless have a nineteenth century spirit that is probably more apparent with time.

It is apt that it should be Vermeer who photographers like Guido Rey and Richard Polak (who worked 1912-1915 in Rotterdam) copied so fastidiously, given the discoveries of Philip Steadman and others of convincing proof of his use of a lens in making his paintings, since logically that would account for the effectiveness of a photographic reconstruction of his paintings.

The lesser-known Carlos Ducoin lived in Lille in northern France and was a hobbyist painter. A baker, he probably took up photography after he retired in 1900. His ‘living sculptures’ do look as if they have been dipped in a dough and dusted with flour, especially in the flat daylight studio lighting he used, but are creditable examples of this genre, though they might these days be a cliché found amongst any city’s ‘living statue’ buskers.

Josef Jindřich Šechtl (1877 – 1954) had a wide variety of interests in photography, including portrait photography and photojournalism. His fine art photography is pictorialist, including his use of the bromoil process.

He worked from the Šechtl & Voseček studio after he inherited it from his father. Their photographs are not usually signed so it is unclear which photographs taken during 1897–1911 were taken by Josef Jindřich or his father Ignác Šechtl (1840–1911).

It was due to Josef Jindřich that the studio started to publish large photo essays on important events, and sold postcards of them, including earliest documented the Sokol gymnastic festival (Slet) in which athletes performed synchronised displays. An associated series of images of ‘live statues’ were arranged for Sokol in 1911 with the sculptor Jan Vítězslav Dušek (1891-1966). The liveliness of these tableaux is due no doubt to the expert gymnasts who were the models, and they are reminiscent of the energy of La Danse, an 1868 sculpture by French artist Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux in Echaillon marble that appears to burst from the façade of the Opera Garnier in Paris.

It would be remiss not to mention Canadian Jeff Wall‘s (*1946) tableaux as prime examples of their application in the postmodern era. In employing the large format view camera he should not be mistaken for a revivalist returning to the kind of historicism we see in Julia Margaret Cameron and Oscar Rejlander (1813–1875). His meticulous planning in re-siting narrative scenes from artists as varied as Hokusai and Manet develops a complex of references that cross between contemporary life and the pregnant moments from art history. His large scale light box display invites the kind of extended contemplation usually devoted to painting.

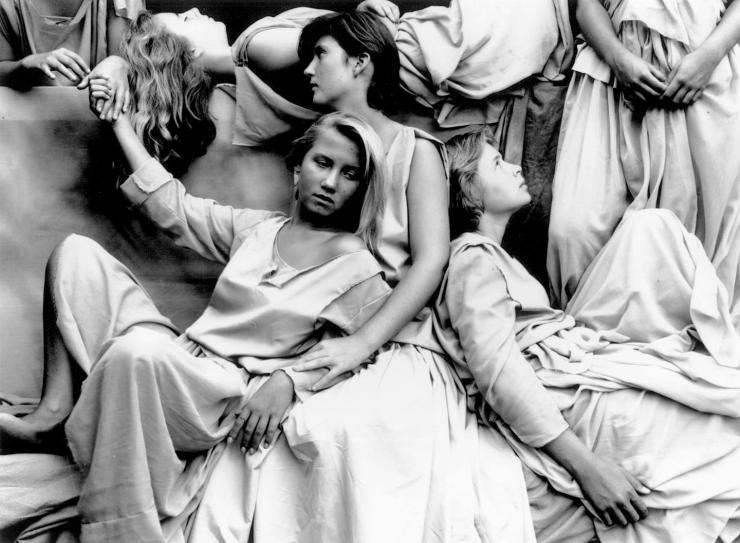

Jeff Wall is discussed exhaustively (overbearingly, I would argue) by Michael Fried in his 2008 book Why photography matters as art as never before (New Haven : Yale University Press). I would prefer to illustrate this development in postmodernism with Scenes on the Death of Nature by Australian Anne Ferran which toured Australia from 1986 until 2006. It consists of six large format black and white prints of intertwined laconic young women draped across one another and dressed in long flowing plain white garments, with appearance of neoclassical sculptures. Here, as in Wall’s imagery, can be read clear reference to art history, but in this case the reference is not specific and is deflected by the works’ harsh black frames that incarcerate the figures and their psychological lassitude.

Ferran’s models were her own daughter and friends. They are quite easily identified as well-groomed and middle class who might look as if they were recovering from a sleepover, though the lack of clues from their dress charges the imagery with further ambivalence. Indeed it is the performative aspect of tableaux vivant and our consciousness that the subjects stand in for other subjects of historical or artistic interest that makes the collaborative effort of the genre engaging. Ferran’s subsequent concentration on the female convict, which has national colonialist relevance, provides a retrospective interpretation of these landmark images in Australian photographic history.

It is the socio-political potential of narrative images, particularly those that redeploy art history that is still of current interest, and for me especially that of British photographer Tom Hunter (*1965). He lived from 1997 in a street in Hackney, a London suburb famous in 1970s photography for Jo Spence and the Hackney Flashers feminist collective. There he occupied squats for 15 years along with almost a hundred others, a location the Hackney Gazette described as ‘The Ghetto’, ‘a crime-ridden derelict ghetto, a cancer- a blot on the landscape’. As part of the fight against eviction, Hunter produced a series of works Persons Unknown that refer to eviction orders they received, the postures and gestures referencing Vermeer’s paintings which dignify the squatter community and their struggle.

His The Way Home (2000) makes direct reference to the Pre-Raphaelite John Everett Millais’ (1829-1896) Ophelia (1851-2), itself a visualisation of Shakespeare’s tragic character in Hamlet. Hunter uses an overgrown pond beside a canal to pay homage to a young woman, lost on her way home in the dark after a party, who drowned. Because the image is so easily recognised from a well known painting it cannot be mistaken as documentary, but becomes allegorical in scope, contemporary beyond the retelling of an old fable, but enhanced by the allusion to enable a recognition of the symbolic and epic qualities of everyday life.

2 thoughts on “November 26: Live”