Writing here is not a solitary activity; I have many helpers and collaborators in the voices of others who are fascinated by this unique medium of photography—their side of the conversation is on my bookshelf, rather like the tiers of a lecture theatre, only in this case that is where the professors sit while I make my notes and ask my questions from the floor.

Writing here is not a solitary activity; I have many helpers and collaborators in the voices of others who are fascinated by this unique medium of photography—their side of the conversation is on my bookshelf, rather like the tiers of a lecture theatre, only in this case that is where the professors sit while I make my notes and ask my questions from the floor.

Among them is Michel (Micha) Auer, born in Zurich on 30 May 1933. Initially a photographer, Auer became a collector of cameras, and that is what led him eventually to become a photo-historian, one of many whose research and words I value, to the extent that, finding him only on the French, German and Czech Wikipedia sites, I’ve spent some hours over the last couple of days translating and expanding on those so you can read about him in English.

A resource of particular use to me is his English/French Encyclopédie internationale des photographes de 1839 à nos jours (Photographers encyclopaedia international 1839 to the present). It is a two-volume set, but furthermore, there are two authors, Michel and his partner Michèle and it is she, I assume, who appears on the covers in solarised images holding a Leica M3.

The Encyclopaedia was a purchase I made in September 2018 after much searching, and with luck I found it for US$17.05 (plus US$10.00 postage). It arrived reeking of cigar smoke which is gradually fading with use, and with the cover of the L-Z volume detached from the spine at the front edge, but repairable; otherwise the 1985 volumes were well-preserved.

I felt I had done well because today I could ill afford the $300+ now being asked for it, but more because it contains information on over 1,600 photographers from around the world, drawn extensively on the authors’ private archives for its historical entries, and on their valuable contacts with living photographers.

In 1997 the encyclopaedia was published on a CD-ROM updated to include full entries on 3,135 individuals and less comprehensive information on an additional 3,000, from seventy-one different countries…another purchase I need to make perhaps, though it’s available in the State Library when I need it, and besides there is an even more up-to-date version online, should one want to part with Sfr 490 (A$1,000 p.a.) to access it, though a basic search is free.

Auer recounts the origins of this enterprise:

In 1983, my wife, Michèle, persuaded me to undertake the enormous project that would later become the International Encyclopaedia of Photographers from 1839 to the Present Day, published in 1985, comprising two substantial volumes. An updated and expanded edition was reissued in 1997 as a CD-ROM.

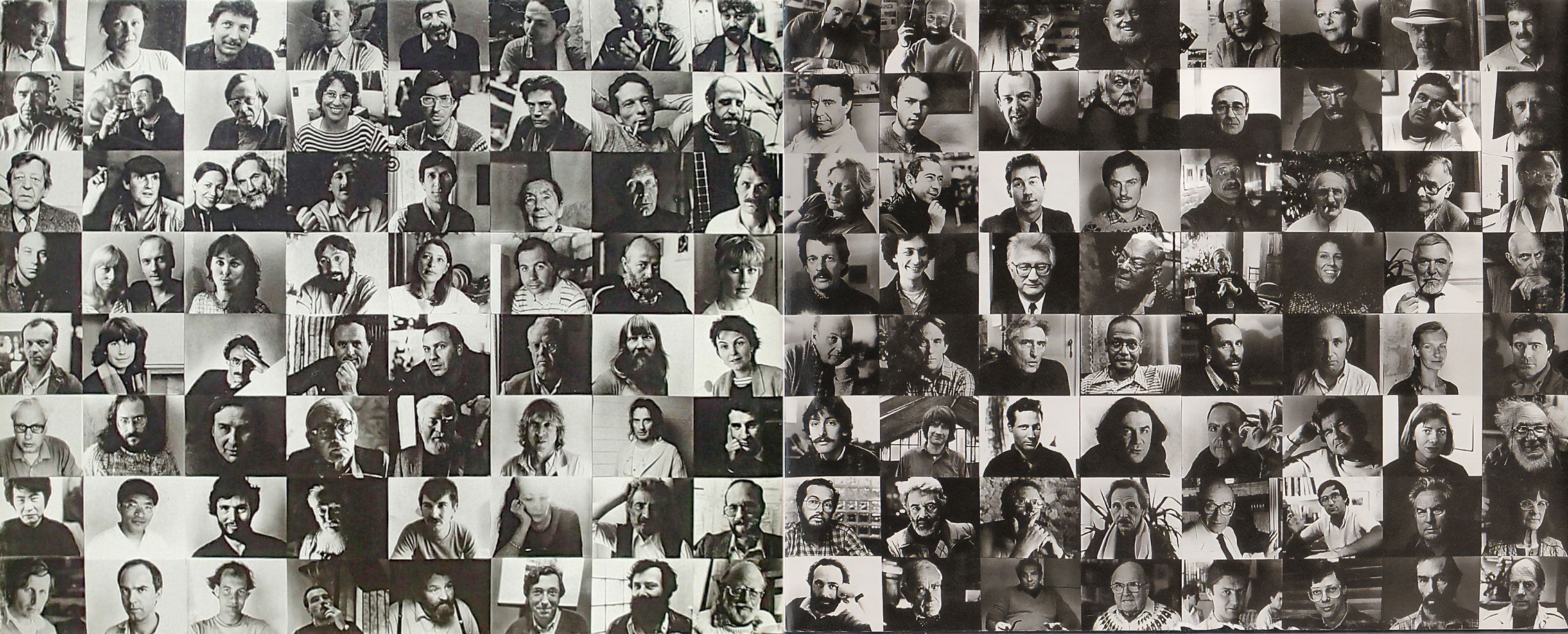

This marked the beginning of numerous visits to photographers and artists, to whom I first had to explain the importance of such a project. Each page was to be illustrated with a work by the photographer, their portrait, and the signature or stamp appearing on the work. We quickly realized that the photographers we visited either did not have portraits of themselves, or only ones dating back a few years… so I decided to photograph them, the beginning of a long series of portraits for the encyclopedia. These portraits are taken at close range, about a metre, often at a table during the interview, with a Leica M equipped with a 50 mm focal length.

Photographers’ pictures may be familiar but their faces are generally not well-known and are found (or hide) behind the camera, so Auer’s portraits, most of them shot in the early 1980s, are of seemingly anonymous people but a few are readily recognised; the jolly gnomish Amish-bearded visage of Ansel Adams and the glowering eyes of Robert Mapplethorpe for example…but what I find so useful about this encyclopaedia—unlike the majority of photography history books—is that in it, Americans are outnumbered by European photographers and others from countries across the globe, though as the sample of the portraits of them below indicates, there are many more men that women. Better copies of many of these are in the International Centre for Photography collection online where you’ll find so many of the faces are a mismatch for your expectations, and often appearances contradict the style of their work.

The renaissance of this magnum opus dates much earlier as Auer himself recalls:

“My first photograph dates from 1946 [after his primary schooling from 1941 to 1945 in Geneva] when I used my mother’s Kodak Brownie No. 2 box whose rollfilm was surplus stock used for aerial photography by the US Army. Some time later, I transformed my parents’ maid’s room into a laboratory. My father encouraged me, giving me his folding 6 x 9 equipped with a Zeiss Tessar lens and a compact shutter.

“In 1948, as a teenager, I asked Santa Claus for a Leica, but it was a Retina that I found under the tree, my uncle being the director of the Kodak laboratory in Renens; I was a little disappointed. The following year, I salivated in front of a used Rolleiflex in the Photo Mercier window, it costs 500 francs. Visiting my father whose office was on Petitot Street, I tried to encourage him to buy me this beautiful machine, but failed. Deciding to save up for it, I started photographing my friends who bought prints, which was easy because the cost of these portraits was paid by their doting parents! In a year I was able to buy another used Rolleiflex and still for the same price.

“In 1951 at the end of sixth form [at boarding school at Glarisegg Castle near Steckborn], I failed one of the matriculation exams. My father, furious, tore strips of me, and sent me to Zurich to take an orientation test at the Akademische Berufsberatung (Orientation for University Studies). Dr. Andina, psychologist and head of the service, summoned my father to Zürich and spent the day convincing him that it is best I take an apprenticeship in photography and not university studies.

“On 15 May 1952, I started a one-month trial internship with Hans Enzeroth, an advertising photographer in Zürich [who perhaps was a hard master, as he’s not listed in the Encyclopaedia], which turned into a three-year apprenticeship. I earn 15 francs per month the first year [worth between A$75-A$135 now, a very low wage], then 35 francs the second year and 50 francs the third. In 1954, I took my end-of-apprenticeship exam in May, which was followed by my “école de recrue” [a core part of Switzerland’s compulsory military service system] in Emmen, training as a telephone operator.”

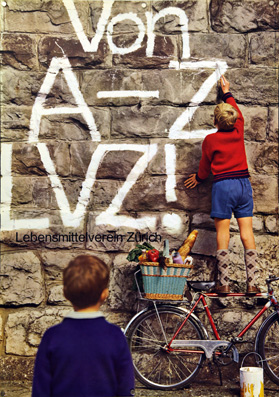

It is intriguing to find at L’œil De La Photographie examples of Auer’s colour work from 1952 (above) for which he received first prize with honours in the apprenticeship competition in 1952. They are a series depicting spaces between public and private, the foyers and hallways of apartment blocks, in Zurich, I assume; some stylishly modern, others a little drab. All follow the conventions of architectural photography, with strictly square vertical and horizontals and carefully exposed to preserve, even on such an unforgiving medium as colour transparency film, the ambience of the lighting.

“At the beginning of 1955, I got a job at Cinégram where I earned 420 francs per month [a value of about A$1,660 in 2025]. I asked too soon for a raise, was refused, then decided to set up my own business. Looking for a low-rent premises, I discovered an arcade at 26, rue des Grottes, and opened [the ‘Big’ laboratory specialising in giant enlargements in B/W and colour] on 5 December 1955, and scouted for business with advertisers, graphic designers, and [directly to] companies. In 1958, I passed my master’s exams successfully [the Swiss tertiary level diploma awarded for expert skills and enabling the holder to run a company and to train apprentices].

“The workshop became too small, we [by this time he had employees] decided to build a workshop villa in Le Grand-Saconnex where we moved in the spring of 1960.”

During this period, Auer married Françoise Guerin and they had three children (Martine, Laurence and Georges Nicéphore). In 1961, abandoning advertising photography, Auer devoted himself to the collection of cameras and the writing of various books on the subject:

“I have always collected many things, since I was a child: pocket knives, radios… But without knowing that I was a collector. I started collecting systematically in 1961.”

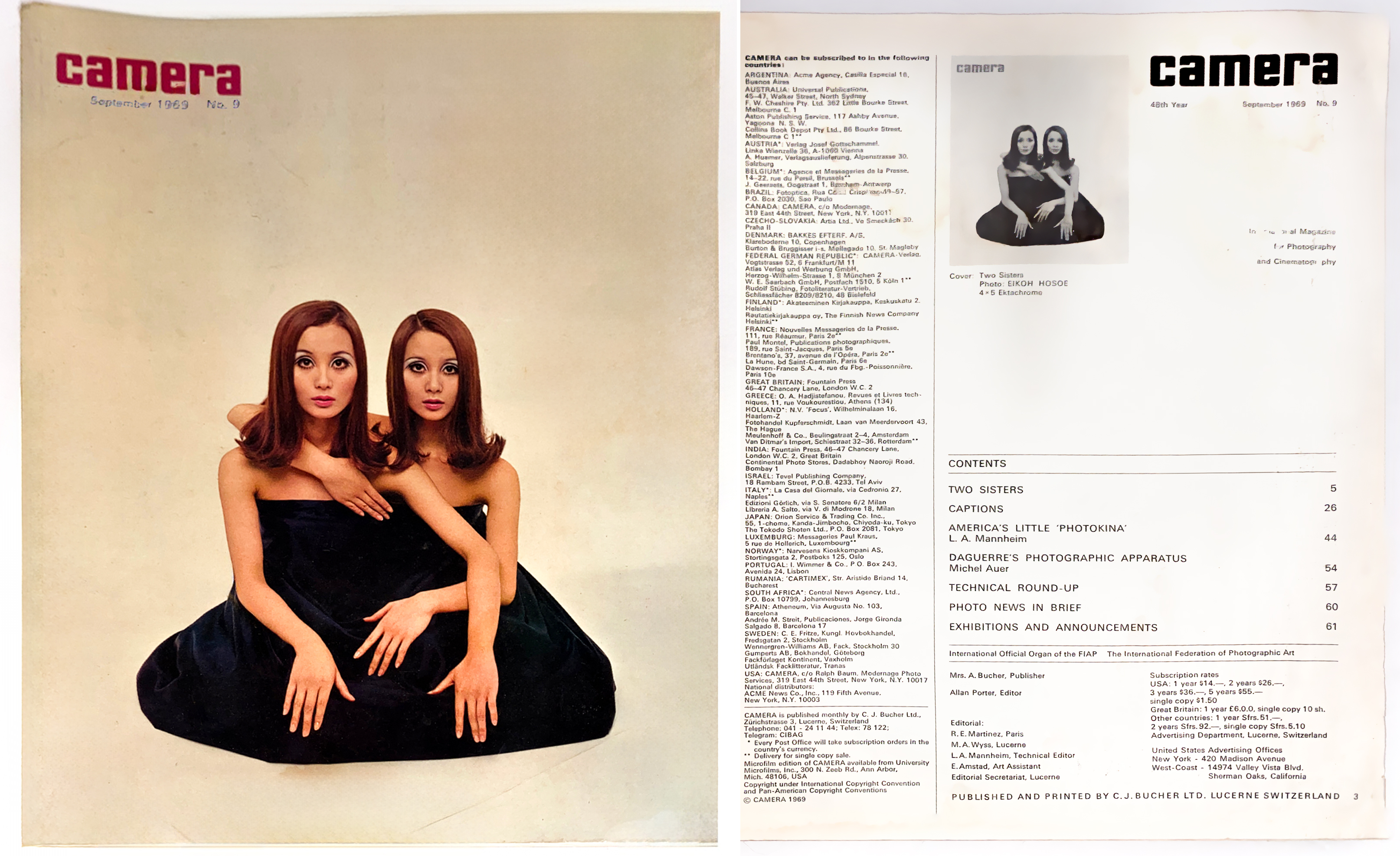

In 1965, he became a corresponding member of the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Photographie (DGPh) in Cologne, Germany. He wrote articles (on cameras and inventors) for the monthly magazine Camera in Lucerne until 1969. The couple divorced in 1968 and he made the first of several trips to America in the early 1970s. In 1971, he gave a lecture at the Polytechnicum in Zurich and then in Vevey in 1971 organised a retrospective exhibition of his collection as the core of a survey of the history of photography, which led to the creation of the Swiss Museum of Photographic Equipment, Vevey which opened to the public in 1979 in an apartment located at Grande Place 5 and moved in 1989 to an eighteenth century building located in the alley of the Anciens-Fossés, restored by the architect H. Fovanna and developed by S. and D. Tcherdyne, museographers.

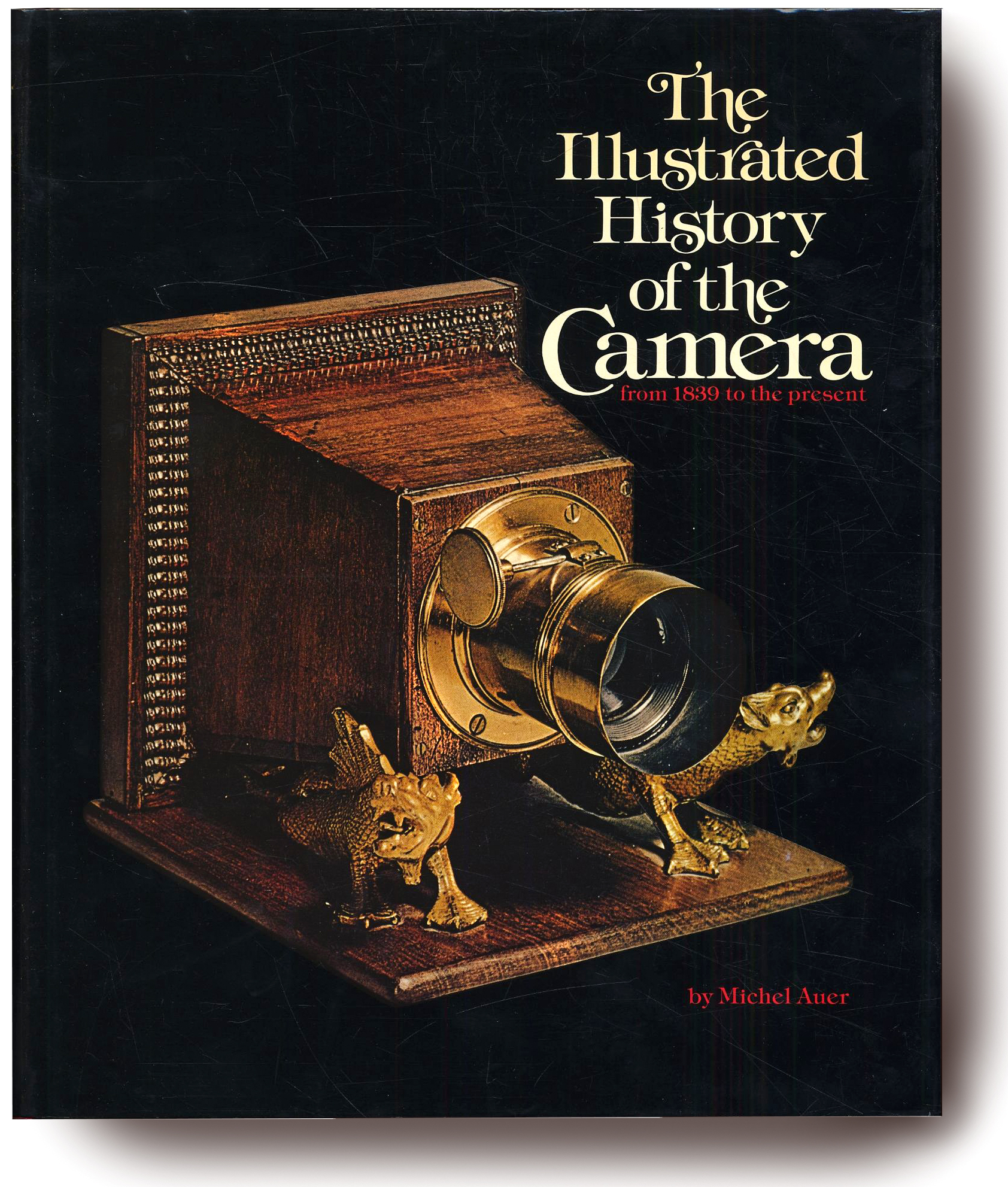

Finding there was little documentation on cameras, Auer was motivated to publish, in 1973, the first reference work on collectible photographic and film cameras, gave a lecture for the 25th anniversary of Sinar in Schaffhausen, and donated part of his camera collection to the Provincial Museum of Antwerp in Belgium. The following year, he organised the exhibition of vintage photography for the inauguration of the Fnac Montparnasse in Paris, alongside Henri Langlois, who covered cinema. In 1975, he published the first major book on the history of cameras at Edita in Lausanne, translated into English and German.

Auer’s Illustrated History of the Camera: From 1830 to the Present was widely reviewed: Michael McNay in The Guardian welcomed it as “a detailed exposition of the development of the techniques of photography”; Judith Hoffberg noted that “since camera technology changes constantly, the book becomes a historical, visual survey of a machine which has changed the world…” She considered that the only comparable book was A Century of Cameras (1973) by Eaton S. Lothrop Jr. which she regarded as “a less sumptuous work that is limited to the cameras in the George Eastman House”.

Michel and Michèle Ory had first met in Paris in 1974, and each had their own camera collection. Micha amassed cameras of all types while Michèle specialised in ‘miniature’ models. At first they kept their collections separate, and as they remembered in a 2017 interview “after ten or fifteen years we decided to merge them. When you are getting to know someone, you never know if you will be together the following year.”

He sold the Big laboratory to his employees and devoted himself entirely to his research, with Eaton Lothrop on spy cameras and with Michèle Ory on amateur ciné cameras.

Having moved to Paris, in 1976, at the Clignancourt flea market in Paris, they operated a stall specialising in cameras and photographs. They lived nearby. They got married in 1980 and merged their collections in 1990. In the meantime, they also made acquisitions together.

In fact Michel possessed at least three different collections of cameras; In 1973 Michel’s first was sold to the Provinciaal Museum voor Fotografie in Antwerp (now FoMU), supplemented since by other collections including that of Agfa-Gevaert. In the early 1990s the JCII Camera Museum in Tokyo added to its holdings of Japanese products examples of Western cameras purchased from Auer. The Auer’s personal collection of rare and significant cameras is kept at the Auer-Ory Foundation.

Amongst photographs sold to museums, the Getty has eighty-nine vintage daguerreotypes, the majority by Jean-Gabriel Eynard, purchased in the 1980s from Michel and Michèle Auer. Eynard, on whom Auer had written an article in 1973 in the Revue du Vieux Genève, was a political influential, immensely wealthy Swiss banker and one of the first Swiss to use the daguerreotype, having learnt the process in Paris, and, aided by his gardener, made pictures of his family, his properties, and daily life in Geneva, mostly for his own amusement, which have become valuable historical documents

Auer became accepted as a world authority on historic cameras, acting as technical advisor for the French television quiz program “La Tête et les jambes” (The Head and the Legs) in 1978; as a member of the Advisory Committee of the George Eastman House in Rochester, NY (1979-90) presenting there in October 1985 at a symposium; being appointed honorary life member of the Photographic Historical Society of New England (PHSNE) in 1979; as advisor for 17 programs on spy cameras for Voss Films in Cologne, 1982. He was a member of the European Association for the History of Photography, co-founder and first president of the Centre de la photographie in Geneva, 1984-94 and Chairman of the committee for the Grand Prix photographique du Grand Passage in Geneva, 1990-93; and in 2004 was advisor for three films by Peter Knapp, Ces appareils qui vous ont vus (‘These Cameras Which Saw You’) for Canal & TV-5.

ISBN: 9780394407708

His transition from camera collector to encyclopaedist came about circuitously.

The photographer Louis Stettner was living in a house Micha owned and which he wanted to sell. Stettner who lived there with his wife and two children would be forced to leave, so the Auers suggested he buy it, but he had no money, but he had photographs; he and Weegee were friends and Louis had published Weegee’s first photo book in 1977 (publ: Alfred A. Knopf, New York).

“We looked at what he had and we reached an agreement, not only for the largest collection of Weegee in the world, 500 of them, but also for works by Brassaï, Michel Favre and by Stettner. We exchanged them for our house. We would have bought Weegee’s work, but not that much. The exchange came from the fact that I had inherited a house, and we couldn’t keep both houses. We had the Weegee photographs appraised and bought them for $225 each.”

They started collecting contemporary photography in 1983 and interviewed over a thousand photographers for the encyclopaedia:

“Some were nice and some were not at all. When you like the person, you’re more likely to like their photography. I had a bad relationship with Cartier-Bresson, although I still think he’s a genius. I think I met him fifteen times. I wanted to take his portrait, and every time I asked him, he said no. At first I didn’t argue with him, but maybe the twelfth time I saw him I said: “How can you do this to me? I’m an unknown young photographer, and I need help and you’re famous, maybe you’re the most important photographer in the world. If everyone said no, no one would be able to take pictures!” And he replied that he didn’t want to be recognized when he worked on the street. We practically don’t have any pictures of him because of that.”

In the following years he took part in numerous conferences on historical photography and in collaboration with Michèle Auer-Ory, organised a variety of exhibitions at home and abroad as well as numerous catalogues and book publications, and in 1985 the Encyclopédie internationale des photographes de 1839 à nos jours. When in 1997 the encyclopaedia was updated and published on a CD-ROM reviewer Peter Blank noted its biographies of “3,135 individuals and less complete information on an additional 3,000, from seventy-one different nationalities,” in a format that he considered “visually pleasing and well organized”.

But does expertise on the development of the camera and gathering biographies of thousands of contemporary photographers make Auer “one of the greatest experts of photographic cameras and the history of photography”?

To look at Australian photographers’ entries in the print version one finds well-knowns Harold Pierce Cazneaux, Max Dupain, Helmut Newton, Rennie Ellis, David Moore, Max Pam, and Graham Howe and Grant Mudford who have spent most of their lives in America, and two who are now quite obscure; photojournalist Bob Davis who had set up a photo agency in Hong Kong in 1983, and art photographer Stephen Roach, identified in the book as Stovin Reach, who went to live in Italy. Mudford and Newton both moved away from Australia to practice overseas. Howe’s entry below is typical of those throughout the Encyclopaedia; the portrait, usually by Michel Auer, with the photographer’s signature as they would sign a print, a biographical timeline in French and English, list of exhibitions, a bibliography of works by and about the person and a sample of their work.

However, historian of nineteenth-century photography and Henry Fox Talbot specialist Larry J. Schaaf in reviewing on 5 November 1998 in Études photographiques the CD-ROM version (published some 12 years later than the 1985 print original) found some errors of fact and others made in translation from the French:

“…the translation errors there are so numerous, so egregious, that they cannot be ignored. Some are easily spotted, so obvious are they; others, more thorny, lead to factual misinterpretations. In short, the translation seriously undermines the professionalism of the whole.”

Checking his assertion, it is clear that such errors are found mainly in information added for the data disc. But Schaaf’s criticism continues:

“But even more serious are the factual errors. Of course, it is inevitable that, in such a volume, there will be divergent points of view and, here and there, a few blunders. But in this case, the frequency of errors is so great that one can no longer trust the information reported. In the technical glossary, how can one not be surprised to read, for example, that wet collodion “was quickly replaced by dry collodion plates”? If this had been the case, much of the 19th-century photography we know would not exist. It would be tedious to list all errors of this type, but given that many novices will be referring to this glossary, it would probably not be too much to expect from a reference work that technical terms be, at least for the most part, correctly defined.

Schaaf, given his expertise as Director of the William Henry Fox Talbot Catalogue Raisonné at Bodleian Libraries, tests the accuracy of the publication on its entry for that pioneer English photographer:

“The first approximation appears in the “historical chronology,” which indicates that Talbot began his research in 1835 (the exact date is 1834). Further confusions follow: the only photograph reproduced in the biographical section is actually a view taken by his friend, the Reverend Calvert R. Jones. Talbot is said to have received financial support from the Royal Society in 1831 for his work in physics and mathematics. However, he never applied for or received such grants (even though he was elected to the Society in 1831). The biggest misunderstanding concerns the year 1833: “After familiarizing himself with the work of Herschel, Humphry Davy and Thomas Wedgwood, he went to Italy with a Wollaston camera and attempted to photograph Lake Como, thus becoming (with H. Bayard) the father of modern photography with the negative process.” However, there is no evidence that Talbot had done any research on photography before his trip to Italy and, on closer inspection, this statement would be even contradicted by his own statements and the words of his contemporaries. Furthermore, he never attempted to photograph Lake Como: on the contrary, it was precisely because he failed to sketch the landscape using the camera lucida that he turned to photography. Finally, it is a disservice to both Talbot and the brilliant and stubborn French inventor Hippolyte Bayard to attribute to them equally the paternity of the negative process.”

Schaaf finds that in the bibliography for that entry lacks reference to what he regards as seminal texts; Gail Buckland’s biography, Fox Talbot and The Invention of Photography (1980), as well as Hubertus von Amelunxen’s book, The Aufgehobene Zeit: The Finding of Photography by William Henry Fox Talbot (1988) and fact-checks the statement that the largest collection of Talbot’s work is in the Science Museum in London, since “it was transfer[red] ten years ago, [to] the National Museum of Photography, Film & Television in Bradford.” To be fair, that error may be due to the transcription from the version published in 1985 to the CD. But Schaaf finds that errors…

“are not isolated to the case of old photographers. Thus, Robert Adamson is said to have used the collodion process, although he died in 1848, several years before its invention. Things are not much better for his associate David Octavius Hill, whose “collections” section does not mention the essential collection of the Scottish National Portrait Gallery and that of the University of Glasgow Library (around 500 original negatives). The entry devoted to Sir John Herschel is illustrated by a cyanotype of which he is not the author, and his biographical sheet mentions that the Royal Astronomical Society of London awarded a gold medal to his father after his discovery of Uranus in 1781; However, the Astronomical Society was not founded until 1820 and did not take the title Royal until 1831. Furthermore, Herschel is wrongly credited with serving as President of the Royal Society in 1848 and as “Technical Director” of the Great Exhibition of 1851. Finally, although his stay at the Cape of Good Hope partly coincided with that of Charles Piazzi Smyth, the latter never served as his assistant there. Indeed, one searches in vain for Smyth in the alphabetical list, until one realizes that he has been inadvertently listed under the letter of his middle name, Piazzi. The entry also fails to mention the only existing biography of him: The Peripatetic Astronomer: The Life of Charles Piazzi Smyth, by Hermann and Mary Brock (1988). The impressive number of more or less benign blunders illustrates the problematic nature of the method used by the authors, essentially based on the compilation of secondary sources, and seriously calls into question the usefulness of this so-called reference work, as well as its claims to authority.

Summing up, Schaaf concedes that…

“Despite everything, one can only admire and encourage the effort made by the Auers to make the mass of information they have gathered accessible to the public. It therefore remains to be hoped that this edition of their CD-ROM will not be considered definitive, and that the authors will have enough energy to undertake a complete revision and meticulous corrections, not forgetting to solicit the expertise and opinions of external contributors. Anyone interested in research in the field of photography should feel obliged to contribute to such an undertaking, as it is true that a work of this type responds to an urgent need.”

Certainly Schaaf’s criticisms hold for the information on nineteenth-century photography, but are they really relevant, and was he the right reviewer for this work? In a minor concession he admits that:

“it is important to believe, for the most part, the information that the Auers gathered from living photographers.”

It is a pity he gives such little attention to this, the very point of the Encyclopaedia, the Auer’s gathering of information about photographers across the world born 1900 and later, and working after the 1970s, in a period in which interest in it was universal. In fact theirs is original research to record history as it was being made, discovering photographers for their publication, rather than merely repeating other sources. They might more wisely have titled their work Photographers encyclopaedia international 1900 to the present, because that is where it is more useful. For the earlier period, one is better to look to Hannavy‘s Encyclopedia of Nineteenth Century Photography (though it was published 23 years later) and in which Schaaf is acknowledged as a member of the board of advisors.

What you will find wonderful about this publication is that it encapsulates that era, and also because, as we see in the case of Australian photographers, the selection is limited (e.g. only 10 Australians in the book, with a further 80 currently added on the website) and sometimes arbitrary. Being dependent on the Switzerland-based Auers’ pre-internet contacts and their considerable library, a consequence is that they gather the obscure amongst the famous…but those lesser-known are inspiring discoveries of some fascinating case studies of workers in the medium who may otherwise have slipped from attention. Some remain insignificant, or have disappeared, like Stovin Reach, but is the striving, but lesser-known, photographer in whom we so often discover inspiration, and it is in the out-of-the-way corners of this vast enterprise of photography— this medium that is about everything— that anyone who calls themselves a researcher should be looking.

In 2009, Michel and Michèle Auer-Ory set up the Fondation Auer Ory pour la Photographie in Hermance near Geneva through which they exhibited their collection of more than 10,000 photographs as well as objects related to photography in single-artist exhibitions held in their foundation, among them Berenice Abbott, Ansel Adams, Ludwig Angerer, Tevfik Ataman, Charles Hippolyte Aubry, Micha Auer, Philippe Ayral, Anna Bak, Édouard Baldus, Marc-Albert Braillard, Mauren Brodbeck, Jean-Christophe Béchet, Christian Coigny, José R. Cuervo-Arango, Serge Diakonoff, Jo Duchêne, Denis Freppel, Jean Le Gac, Werner Gadliger, Aris Georgiou, René Groebli, Philippe Gross, Bernard Guillot, Yves Humbert, Vanna Karamaounas, Peter Knapp, Roland Laboye, Joel Leick, Rudolf Lichtsteiner, Gérard Lüthi, Jacqueline Meier, Yan Morvan, Rafael Navarro, Pascal Nordmann, Françoise Núñez, Marianne Pettavel, Bernard Plossu, Philippe Pétremant, Louis Stettner, Pierre Strinati, Olivia Malena Vidal, Charles Weber, and Rene Zurcher.

They also initiated numerous off-site showings, in Saint-Gervais for example as well as at the Commun du BAC, and in 2004, the Musée d’art et d’histoire, then directed by Cäsar Menz, reserved its ground floor for them. Prior to the Fondation being opened they made loans from the collection, of works by photographers as diverse as Nadar, Weegee and 19th-century Swiss-French pioneers, were made to curators of exhibitions such as Roland Leboye for New York, Weegee the Famous at Le Pavillon Populaire, Montpellier, from 15 September 2008 (281 original large-format prints of the 1930s–1960s, including the Coney Island series (1940) and Heatspell of 23 May 1941); Michel Bépoix for Nadar: Michel and Michèle Auer collection at the Art Gallery of the General Council of Bouches-du-Rhône (2001); and for Alexandre Fiette directing the Maison Tavel in Geneva, a body of work related to French-speaking Switzerland that they had been building since the early 1960s (27 November 2019–29 March 2020).

Their foundation’s collection of photographers’ books is prodigious, with more than 20,000 titles, resulting in Michel’s presenting in a session with Gerry Badger at Vienna PhotoBook Festival in 2015, and another book photo books which displays and provides previews of their holdings.

Marine Vazzoler in Le Journal des Arts, of 24 January 2017 reported that, short of the €93,000 to cover its annual operating costs, they would have to sell some of the collection, or close unless supporters respond to their appeal. However they were able to continue exhibitions albeit less frequently. They were showing Werner Gadliger, a street photographer and portraitist of artists (including Micha, below) when Michel Auer died in October 2024 at the age of 91.

![Spy cameras Auer, Michel; Lothrop, Eaton S. (1978). L'Oeil invisible: les appareils photographiques d'espionnage [The Invisible Eye: spy cameras] (in French) (1st (French) ed.). Paris: Éditions EPA. ISBN 9782851200686](https://i0.wp.com/onthisdateinphotography.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/spy-cameras.jpg?w=332&h=442&ssl=1)

![Ciné Auer, Michel; Ory, Michèle (1979). Histoire de la caméra ciné amateur [History of the amateur movie camera] (in French). Les Editions de l'Amateur. ISBN 9782859170110](https://i0.wp.com/onthisdateinphotography.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/cine.jpg?w=428&h=442&ssl=1)