Currently exhibited at Castlemaine Art Museum until 28 September 2025 is A modern turn, drawn from the collection, and comprised of works from the post World War II period, including photographic portraits of the artists.

Currently exhibited at Castlemaine Art Museum until 28 September 2025 is A modern turn, drawn from the collection, and comprised of works from the post World War II period, including photographic portraits of the artists.

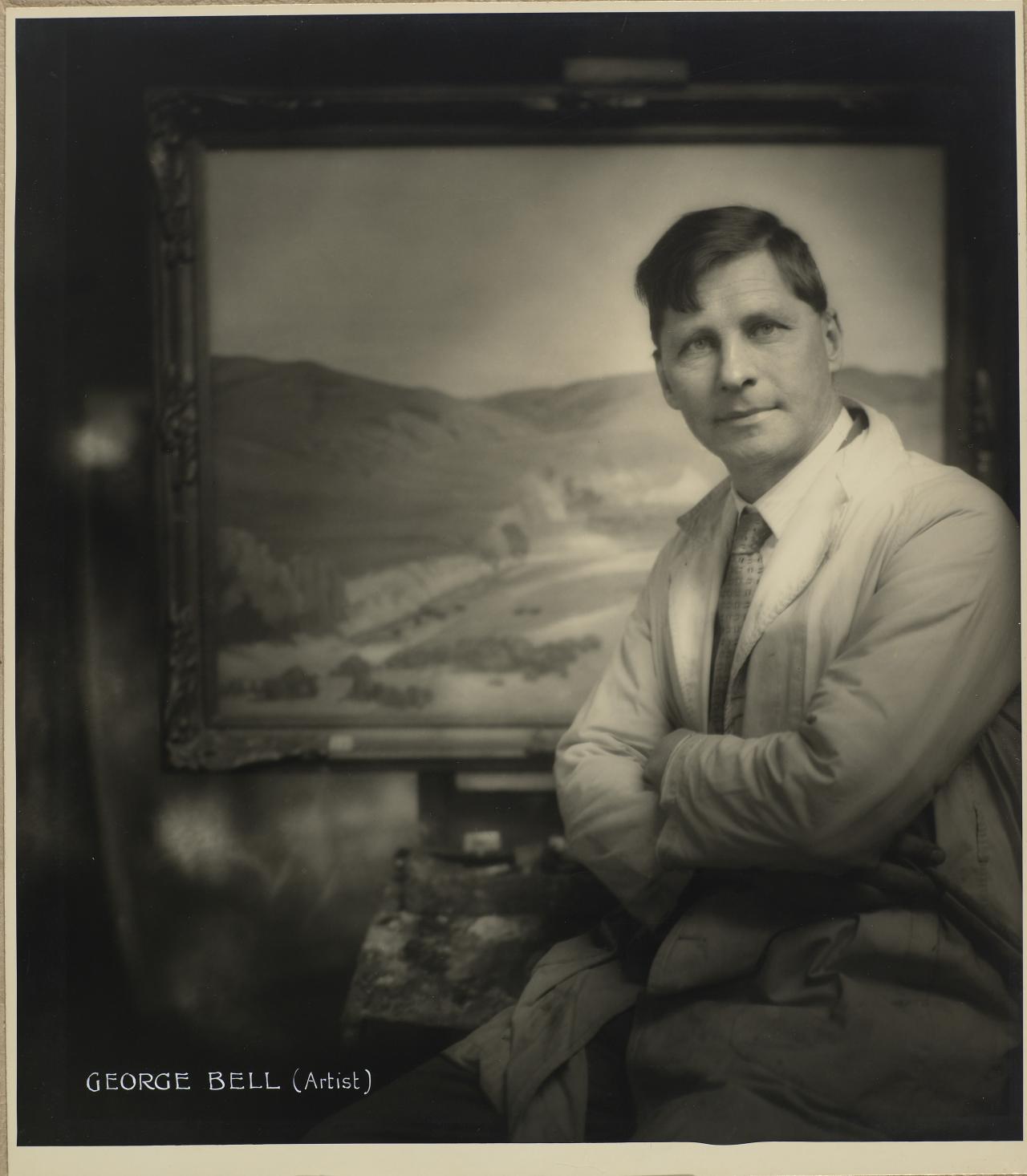

Many are connected to the Contemporary Art Society in Melbourne and to George Bell who led it, and who taught many of the exhibitors.

Bell initially had detested modern art when he saw it in Europe in 1904…

…but he came to understand it and promote it against the early 20th-century Australian art establishment that was dominated by traditionalists such as Max Meldrum (a proponent of tonalism whose disciples are dominant in the CAM collection), and James (‘Jimmy’) S. MacDonald, Director of the National Gallery of Victoria. MacDonald was notably critical of modern art, describing it as “the product of degenerates and perverts” in the press. His tenure at the NGV ended with his abrupt dismissal in 1941.

In contrast, George Bell (1878–1966) emerged as a leading advocate for modern art in Australia. Educated at the National Gallery School in Melbourne and further trained in Paris and London, Bell was influenced by European modernist movements. Upon returning to Melbourne in 1920, he began teaching privately and, in 1932, co-founded the Bell-Shore School with Arnold Shore, which became a hub for modernist art education in Melbourne. Bell’s pedagogical approach emphasised structured design and the imaginative reconstruction of visual experience, drawing on the theories of English modernists Roger Fry and Clive Bell.

In direct opposition to Attorney General Robert Menzies’ establishment of the Australian Academy of Art in 1937, which aimed to promote traditional art forms, Bell founded the Contemporary Art Society (CAS) to support and exhibit modernist works.

The 1939 Herald Exhibition of Exhibition of French and British Contemporary Art curated by Basil Burdett and commissioned by Sir Keith Murdoch brought over 200 works by modern European masters to the South Australian gallery 21 August 1939, then the Melbourne Town Hall from 16 October 1939, and thence to Sydney in the David Jones department store November–December (the AGNSW wouldn’t take it).

The collection included works by Cezanne, Dali, Picasso, and Modigliani. It arrived in Australia just as World War II was beginning and remained in the country until the war’s end and some say it rescued important works from the Nazi vandalism of modernist art. The exhibition is a major focus of Richard Haese’s celebrated 1982 Rebels and precursors : the revolutionary years of Australian art. The inaugural exhibition of the Contemporary Art Society opened at the National Gallery of Victoria in June 1939, just preceding the Herald Exhibition.

Throughout his career, Bell mentored a generation of Australian modernists, including Russell Drysdale, Sali Herman, and Fred Williams. His influence extended beyond his students, as he played a pivotal role in shaping national debates on art education and the role of modernism in Australian culture.

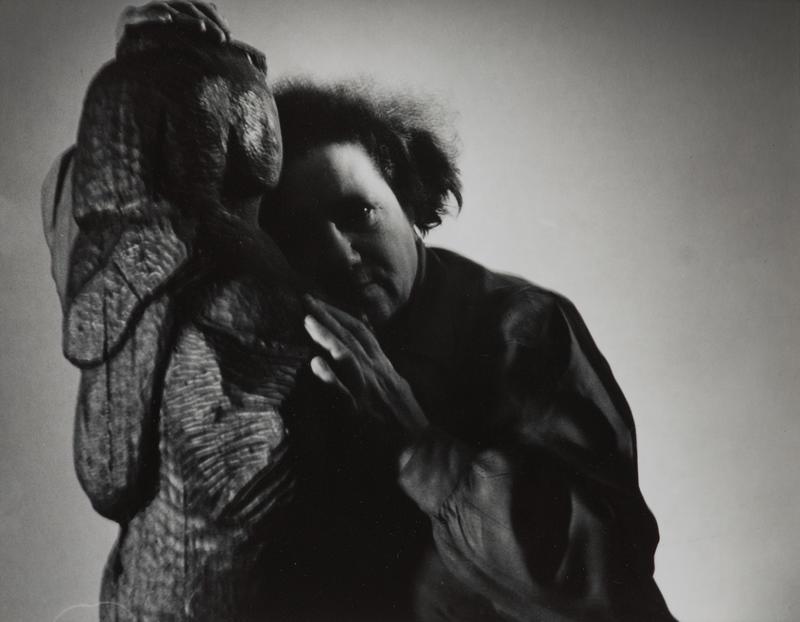

In one corner of this show are photographs, portraits of some prominent players in this modernist movement. These include prints by Wolfgang Sievers, Hugh Frankland and Richard Beck.

The Sievers is a rather rare venture by him into portraiture. Four of the five most important photographers working in Melbourne in the 1950s were German born—Helmut Newton (Neustädter), Henry Talbot (Tichauer), Mark Strizic and Sievers himself—émigrés shaped by fascism and war. Talbot and Newton arrived as wartime internees, with Newton later establishing a fashion-focused practice and collaborating closely with Sievers who had arrived as an emigrant in September 1938. Both adapted to commercial demands, with Sievers initially photographing anything for income, ‘portraits, even babies, even a wedding or two, and dreary, purely commercial jobs,’ before specialising in architectural and industrial commissions as postwar Melbourne boomed and opportunities for commercial photography grew. Sievers used his European heritage and experience to collaborate from the 1950s with leading architectural firms and architects of the day, including Yuncken Freeman and Bates, Smart and McCutcheon

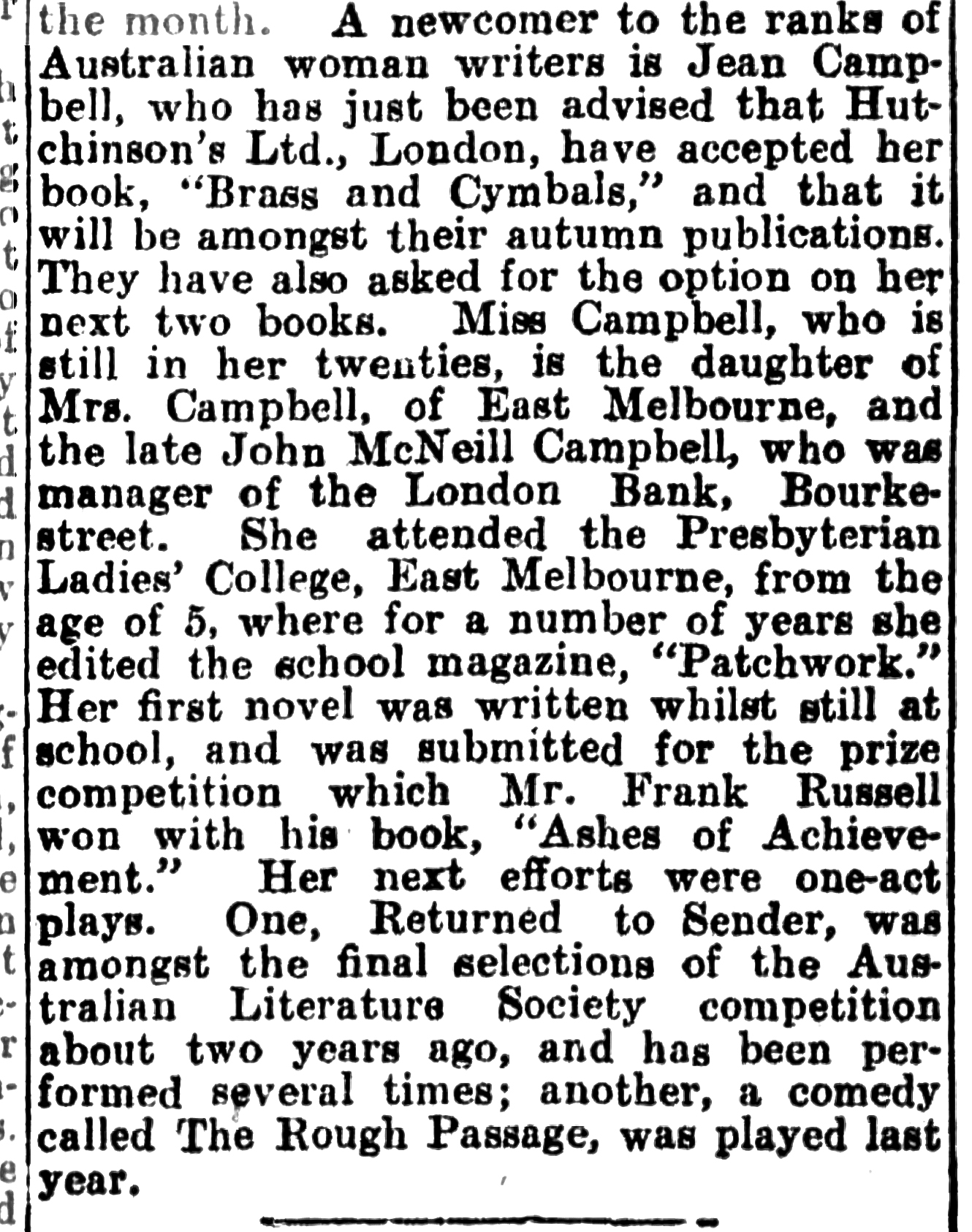

The Sievers is in fact a double portrait of actress, writer and critic Jean Campbell (1901-1984) writer of five novels for William Hutchinson, publishers, in London, which also produced fourpenny magazine style romance novels for New Century Press, Sydney; “A new title every month.” Her novels and articles for the Australian Journal were serious writing, but Bitter Honeymoon, Passion from Peking and Her Fate in the Stars were bread and butter.

Wolfgang Sievers (1956) The writer Jean Campbell, in her flat in East Melbourne, gelatin silver photograph, 24.0 × 17.8 cm, stamp on reverse WOLFGANG SIEVERS / PHOTOGRAPHY / 9 COLLINS STREET. / MELBOURNE, C.1. / CENTRAL 4023

In undertaking this portrait in 1956 (as Helen Ennis dates it in her 2011 monograph on him) Sievers has exercised the same fastidious care as he would in 1958 photographing ICI House, Melbourne’s first skyscraper and he gives Jean’s black-clothed corpus an equal gravitas.

We find Campbell curled on a cozy well-worn corduroy-covered couch in her tiny East Melbourne flat—a single bedroom, with bathroom attached, a small kitchen and sitting room, tucked behind the rather grand Georgian-style house at 17 Powlett Street—taking a pause from writing to conjure her next protagonist from stage right. Sievers has been careful to frame that posture, including her shadow from his main light (another fills from the left), and significant elements that signify her presence as of the bohemian artistic circles of her city; her burled bakelite fountain-pen, densely-filled notebook, stack of notes, the top sheet showing a sketch, and an open book for reference.

The painting slanting into the corner of his frame also looks pensive, and the parchment shade of the table-lamp under the oriental scroll perches askew like the pink hat. It is a portrait of Campbell by Lina Bryans which can now be seen in the National Gallery at Federation Square. Titled The Babe is Wise, after the title of one of her most popular books, the painting presents her as a young, fashionably dressed woman who exudes independence and self assurance from under her jauntily cocked hat. Another print of Sievers’ portrait in the National Gallery of Australia is described as “prepared for a luncheon given by Hutchinson representative George Sutton when Brass and Cymbals was published”. Hutchinsons obviously saw her as a promising author and were prepared to spend on a professional photographer to promote her image.

In 1975, Campbell was the subject of Paul Cox’s film We’re All Alone My Dear on which I, as a Prahran College student, was operator of the Bolex cine camera for scenes in the corridor of the old people’s home in which she then reluctantly resided. It was over the back fence of Cox’s house in Murray Street, Prahran and adjacent to Victoria Gardens in which we filmed a long-shot of her slowly walking with a visiting companion. We saw another side of Paul there, not the pipe-smoking philosopher, but the control-freak auteur shouting orders and organising crew and terrifying the amateur, elderly actors. Jean, an accomplished actor, took it in her stride. As the author of a number of books on Australian art, and art critic for The Advertiser and Courier-Mail at around the time of this photograph and until the year before Cox made his film, she would have sympathy for his artistic flights of passion.

Hubert (Hugh) Samuel Lazarus a.k.a. Hugh Frankland’s portrait of the sculptor Ola Cohn, while suffering camera shake, or because of it, has an expressionist quality; the vibration reinforces the staccato chisel marks in the rough-hewn timber form that Cohn embraces tenderly.

In 1950 after the failure of his second marriage Hugh had returned to Melbourne, determined to turn his hobby, photography, into a business. He set up portrait studios, first in Queens Road, South Melbourne and later in Collins Street in the city, near Sievers’ own.

In 1951 he befriended Charles and Barbara Blackman who lived then in a tin shed behind a terrace house in Powlett Street, East Melbourne. Thus, coincidentally, they were neighbours of Jean Campbell, and Ola Cohn (who was at 43 Gipps St.). Frankland photographed Barbara Blackman who was then working as a life model for artists in order to supplement the couple’s income, and he was the first to buy a Charles Blackman painting, at considerable financial sacrifice—his photography business was just then starting up and he, like the Blackmans sometimes went hungry.

Through the Charles and Barbara, Hugh met and photographed John Yule, Ola Cohn, Donald Friend, John Perceval, Arthur Boyd and Fred Williams, his payment frequently being gifts of paintings. He also purchased many of the works of these artists, for the inherent quality of the paintings rather than for any expectation of future commercial gain, since they were then unknown. The State Library of Victoria holds many Frankland negatives of works of these artists, including murals painted by Arthur Boyd in the dining room of Martin Boyd’s ‘The Grange’ at Harkaway in the foothills of the Dandenong Ranges.

In 1951 Hugh married his third wife Helen Betty Dunning, always known as Bet, and they started married life in a flat in Elwood. In addition to Hugh’s photography interests, he was the Melbourne agent of the French Ciné Pathé film company, whose films he imported into Australia, and he enjoyed making home movies himself, including a blue movie with the Blackmans titled L’Coq d’Amour. He also painted, and was a member of the Victorian Artists Society. Hugh and Bet also established a clothing manufacturing business called the Pioneer Uniform Service and they purchased in Cheltenham, meeting my father Brian in neighbouring Beaumaris who used Hugh’s photographs in Walkabout magazine which he edited. We remember he and Bet as warm friends of our family.

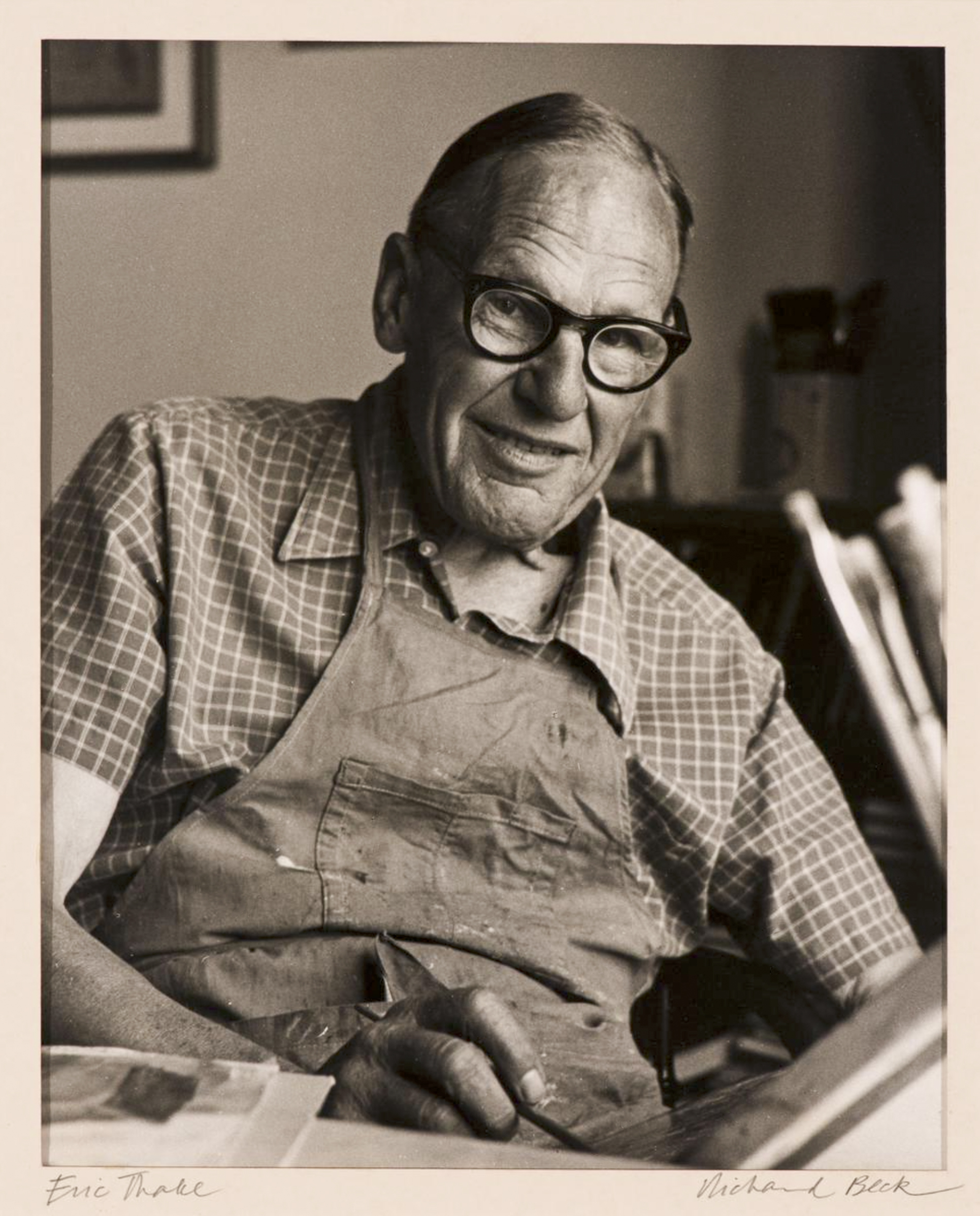

The third photographer, of two portraits of artists in A Modern Turn, is Richard Beck (1912–1985, and not b.1945 as recorded in the CAM online catalogue). Trained at the Glasgow Academy and Sevenoaks School in Kent, the Slade School of Art in London and the Blocherer School in Munich before he migrated to Australia in 1940, Beck served with the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) in WW2 and in 1943 married Joan Barbara Isaacson. After the war, Beck established Richard Beck Associates, design consultants for advertising and industry, producing packaging, corporate image design, exhibition and general advertising work – including freelance designs for several Melbourne advertising agencies including George Patterson, Patons Advertising, Castle Jackson Advertising, and Walker, Robertson, Maguire. His portraits are distinctive in their animation; Eric Thake, the printmaker only eight years older than he, and also a significant photographer, joins cheerfully in the photographic process which foregrounds his art-making.

Dorothy Braund approached Bell in 1943 to study art with him but as she was still only seventeen, Bell recommended that she enrol at the National Gallery of Victoria Art School. Instead she began studies at RMIT in 1944 but found covering industrial design, lettering, clay modelling and drawing too busy, so in 1945 studied at the National Gallery School under William Dargie, Murray Griffin, and Alan Sumner. The latter taught the modernists an analytical approach she enjoyed and she won prizes for figure drawing and still-life painting. Sumner sent Braund and other students to the George Bell for extra study and he became a major influence in her work before she subsequently studied in England 1950–51, then taught art in Melbourne schools Lauriston, St Catherine’s and Rossbourne House. After meeting John Reed she joined the Contemporary Art Society in 1952, where she became a regular ‘Thursday night’ participant at George Bell Studio from 1954. She hitch-hiked in the 1950s and 60s across Europe to Italy, Pakistan, Persia, Turkey, India and Asia seeing the galleries and exploring, and in 1958 visited George Johnston and Charmian Clift and their three children on Hydra. She was a supporter of Bell’s pedagogy and taught some of his former pupils after Bell’s death in 1966. Braund, here aged about forty, ignores Beck’s camera and, perched on a sturdy studio stool in front of a paint-encrusted trolley, is preoccupied with her painting which she squints at with some bemusement. Her strikingly striped pedal-pushers rhyme visually with the interleaved forms on the canvases behind her.

Chris Beck, the last of Richard and Joan’s children, inherited his father’s interest and talent in photography. He remembers:

Chris Beck, the last of Richard and Joan’s children, inherited his father’s interest and talent in photography. He remembers:

“As a child, I would play with toy cars on the floor of my father Richard’s office, as he drew with a nibbed pen and pressed Letraset onto the page to create graphic images for advertising agencies.

“I was a lazy kid and marvelled at his ability to earn a living with the stroke of a pen—he even let me create a symbol, that he improved on, for one of his clients and bought me an ice-cream—more wonderful still was the seemingly effortless way Richard Beck created iconic images and his bold refusal to bargain when agency heads balked at his prices.”

“The Coonawarra wine label, featuring a woodcut of the winery, is still the most recognisable Australian wine label, more than 70 years after the company was forced to build the path that my father imagined for it, when visitors, perplexed, asked why they couldn’t find it on the property.”

“The curator of a 2012 exhibition of historic Olympic posters, unaware of my relationship with my dad, confided in me that his 1956 Olympic Games poster was his favourite amongst posters by David Hockney, Andy Warhol and Roy Lichenstein. That example was why I decided at an early age not to strive to be famous, but to be respected by my peers in whatever I did, just like my father, who never promoted himself, which was another trait I admired.”

After freelancing for most of his working life in England and Australia where he became a leading modern designer of the 1950s and 1960s, Richard took a job teaching graphic art at Prahran College in 1969 for which he designed its logo. After a heart attack in 1972, he left teaching to resume his graphic design career at the age of 60, but, as Chris concedes “like music and fashion, times had changed and younger designers, some whom my father taught, were in vogue.”

“He got some work but he turned to other creative ways to make a living while my mother, after raising four children during the time of one income households, took on various jobs and created a catering business to make up the difference.

“He was friends or acquaintances with many artists and struck on the idea of immortalising them in their studios with his trusty Rolleiflex and selling the images to the Victorian National Gallery for prosperity.

“His photographs of artists, including Brett Whiteley and Fred Williams, are housed in galleries and museums in Australia, while his graphic design and posters are internationally displayed, including at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

“He built a darkroom in a bedroom vacated by my older siblings and got to work. I developed an interest in photography as a teenager helping my father, sloshing the prints in and out of chemicals.

“As a 16-year-old, I had been accepted at RMIT on the strength, I found out later, of my father’s legacy. The head of the art department discovered early on that despite my heritage, apart from amusing cartoons, I had no ability with the fundamentals of drawing, painting or sculpture. Far from being demoralised I turned to photography, and Mushroom Records and independent labels gave me some work photographing bands.

“My father died in 1985, before I vowed to use the inventiveness he had nurtured in me in the darkroom and from his favourite armchair. He would draw on a pipe as he nestled a glass of red and quietly entertained us with stories about history, artists and their art, his days as a camouflage expert in Tahiti during WW2 and the Quakers, whom he admired for their simplicity and humanity.

“He never boasted about the awards he received or the admiration of his fellow and upcoming designers (he was posthumously, the first inductee, with fellow designer Les Mason, in the AGDA Graphic Art Hall of Fame in 1992).”

“I was accepted in the photography degree at Prahran College in 1984 on the strength of a folio, that my father looked over and encouraged me to present. This time John Cato, the head of the photographic department excused himself from deliberation because he knew my father, but I scraped into the final 16 anyway.

“My father was a shy man who enjoyed solitude and despite having a good sense of humour was known for getting the joke a week later. My mother was a bright, talkative woman more interested in other people than herself. For a Prahran class I made photos of her surrounded by people and him alone on the beach, him contemplating with glass of red in hand and her happily chatting with a cup of tea and biscuit concluded with them together on a bench kissing.

“That is one of only two of my photos I framed for my wall. The other is from my next assignment, a series of people’s relationship with their dogs (I later published a likeminded book). My father was in in poor health in his 70s and our dog was 16 and they walked gingerly around the house and napped together every afternoon. But every morning they let loose on the beach and I captured them in a joyous moment.

“It was becoming clear I had no interest in the pure art of photography. I wanted to tell stories about people, life as we believe it to be or don’t. John Cato had a stern but understanding talk with me and I left Prahran College before the end of first year to pursue my calling.”

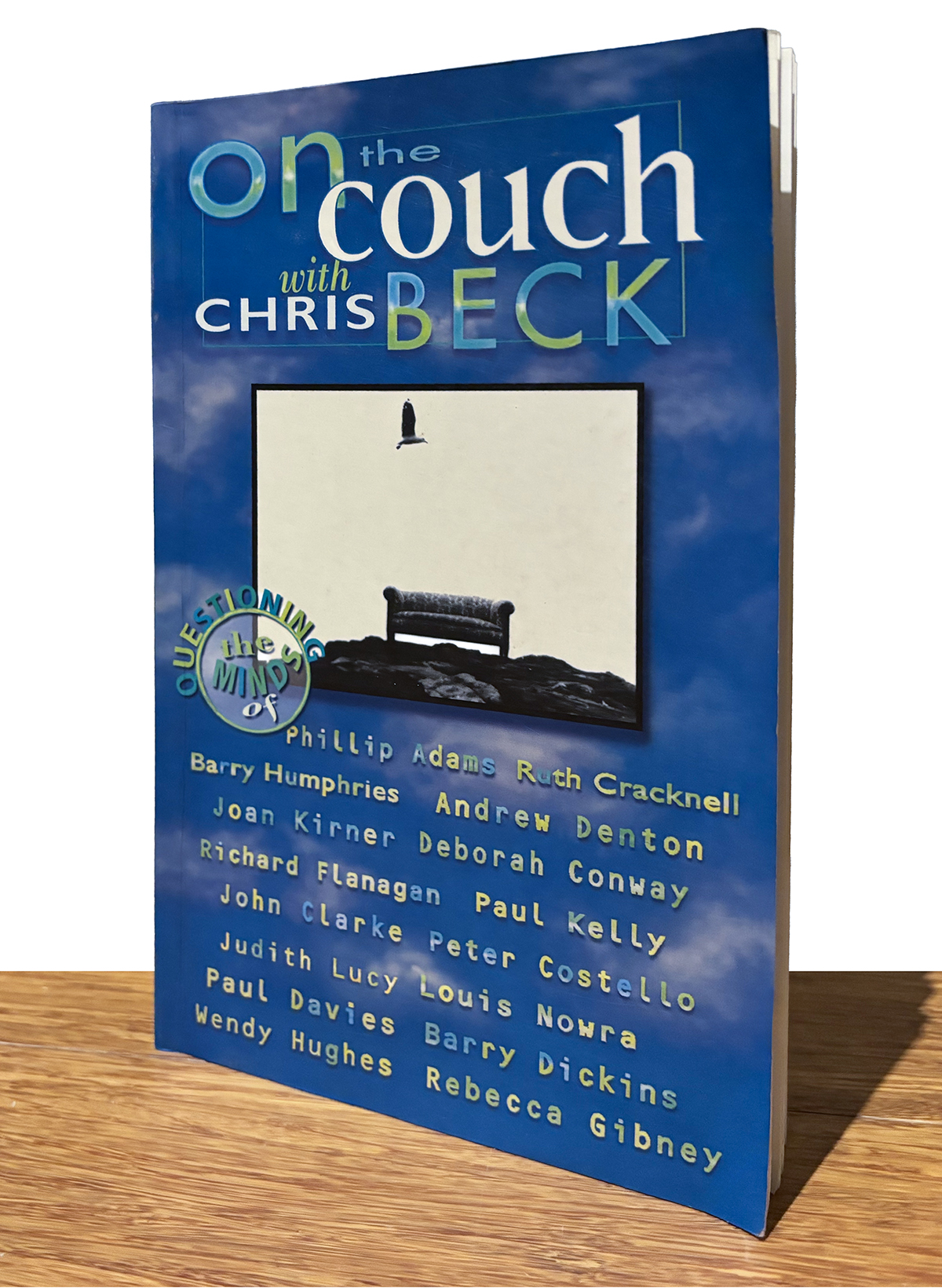

“After working with local papers and freelancing briefly in London, I landed a job at the birth of The Sunday Age in late 1989. Soon I was writing stories and taking photos. I came up with column ideas for the ‘EG’ entertainment section that led to ‘On the Couch’ for The Saturday Age, which lasted six years before I pulled the pin. I always believed my idiosyncratic approach to delving into a person’s mind was a combination of my questioning life when mentally wobbly, my mother’s seductive interest in people and my father’s creative philosophy. It wasn’t an intellectual approach but always inquiring as though the interviewee was helping me. The portrait was as important as the interview in revealing the subject.”

The series was exhibited at the Centre for Contemporary Photography, Fitzroy, in September 1994.

“A book drawn from the column was published by HarperCollins. Andrew Denton, who had told me he read ‘On the Couch’ every week from Sydney, hired me as the writer for the ABC interview series, ‘Enough Rope with Andrew Denton and Elders’ (2003-2010).”

“A book drawn from the column was published by HarperCollins. Andrew Denton, who had told me he read ‘On the Couch’ every week from Sydney, hired me as the writer for the ABC interview series, ‘Enough Rope with Andrew Denton and Elders’ (2003-2010).”

In researching Chris’s book one finds, apart from Michael Leunig’s amusing and extended foreword to the book, an uncredited 29 October 1996 review published in Tharunka student magazine, of the then New South Wales University of Technology (now UNSW). That, amongst several reviews appearing at the time, provides the most incisive insight into the approach Beck used for the interviews and photographs it contains:

“Catering to the cult of personality and introduced by Michael Leunig, this book is a surprisingly entertaining compilation of interviews with various celebrities. Chris Beck is a photographer and columnist for The Age, his softly-spoken, inquisitive interview technique a breath of fresh air from the self-gratifying intrusions most pop-culture vultures push. Instead of asking questions that concentrate on the fame and achievements of the interviewee, he uses direct and simple observations to bring-out the motives and philosophy of his subjects.

“Like a psychologist, he lets them ramble on about themselves, directing them with seemingly innocent little questions, encouraging them to open up instead of putting words into their mouth. The focus is always on what makes them tick, not what they’ve done.

“Amongst the sixty-five characters he investigates in this book are Kate Fischer, Jimeoin, Deborah Conway, Denton, Peter Costello, Poppy King, David Williamson, Ruth Cracknell, Phillip Adams, and Judith Lucy…Egotists, exhibitionists, politicians and people, their souls searched and laid bare before us in soudbite size. The responses and anecdotes he illicits [sic] are frank, honest and more amusing than the usual, Jimeoin talks about having dark thoughts about shooting Ray Martin, Phillip Adams about inserting Logies up Ray Martin’s arse, Kate Fischer says she is proud to be a dumb tit-joke. It’s incredible what prima donnas will say, given a slightly off-beat, receptive listener. Beck’s imaginative black and white portraits also accompany each interview, rounding off a book well worth buying.”

He collaborated with Leunig on another book Dogs and Lovers, published in 2000.

Chris also produced a photographic book, exhibition and images for the 2007 ABC TV series, following a choir of homeless people around Victoria and ultimately to the Sydney Opera House.

Chris writes that he “continued to work in photography, but mostly in combination with writing for publications. I am forever disappointed that my father never saw me working in the creative industries with some success. If it hadn’t been for that short time at Prahran College discovering the edifying brilliance of the great photojournalists, I doubt I would have had the privilege of discovering and retelling ideas and concepts about life through researching, talking to and photographing people from all walks of life.”

Chris Beck is currently showing with other Prahran College alumni in Beyond the Basement at MAGNET Galleries in the Docklands, Melbourne.

2 thoughts on “May 7: Modern”