Anyone writing about photographers craves direct communication with the subject and for that, galleries and art organisations are often the best conduit.

Anyone writing about photographers craves direct communication with the subject and for that, galleries and art organisations are often the best conduit.

Even with the personal contact, contextual information is invaluable—all the more so in the case of photographers and photography of the past.

Authoritative resources are sought, and encyclopaedias and dictionaries are always a first resort, and for Australian art, these have been rare.

So the recent announcement of the loss of funding by, and consequent relocation and winding-back, of Melbourne’s Centre for Contemporary Photography after 40 years, is disastrous news.

Still more astonishing than this downsizing of a bricks-and-mortar state institution is the news that the University of New South Wales is wanting to divest itself of responsibility for an invaluable resource for international historians of Australian art and design—including photography—one that exists in ‘virtual’ space, with only digital data to house, and a worthy project that is the work predominantly of volunteers: Design and Art Australia Online (DAAO)

Joanna Mendelssohn, the founder of this site was one of the first graduates in Fine Arts at the University of Sydney, studying under Bernard Smith and Donald Brook, and is a frequent commentator on Australian photography. She writes for The Conversation which is a leading Creative Commons online publisher of academic research in accessible form. It was initiated here in Australia in 2011 with support from University of Melbourne and since has editions in the UK (2013), the US (2014), South Africa and France (2015), Canada, Indonesia and New Zealand (2017), Spain (2018), and Brazil (2023).

Ten years ago, in April 2014, Mendelssohn wrote on The Conversation an article entitled How the internet liberated Australia’s art history. Her subject was Design and Art Australia Online (DAAO) which has transformed Australian art history by making it more accessible and inclusive.

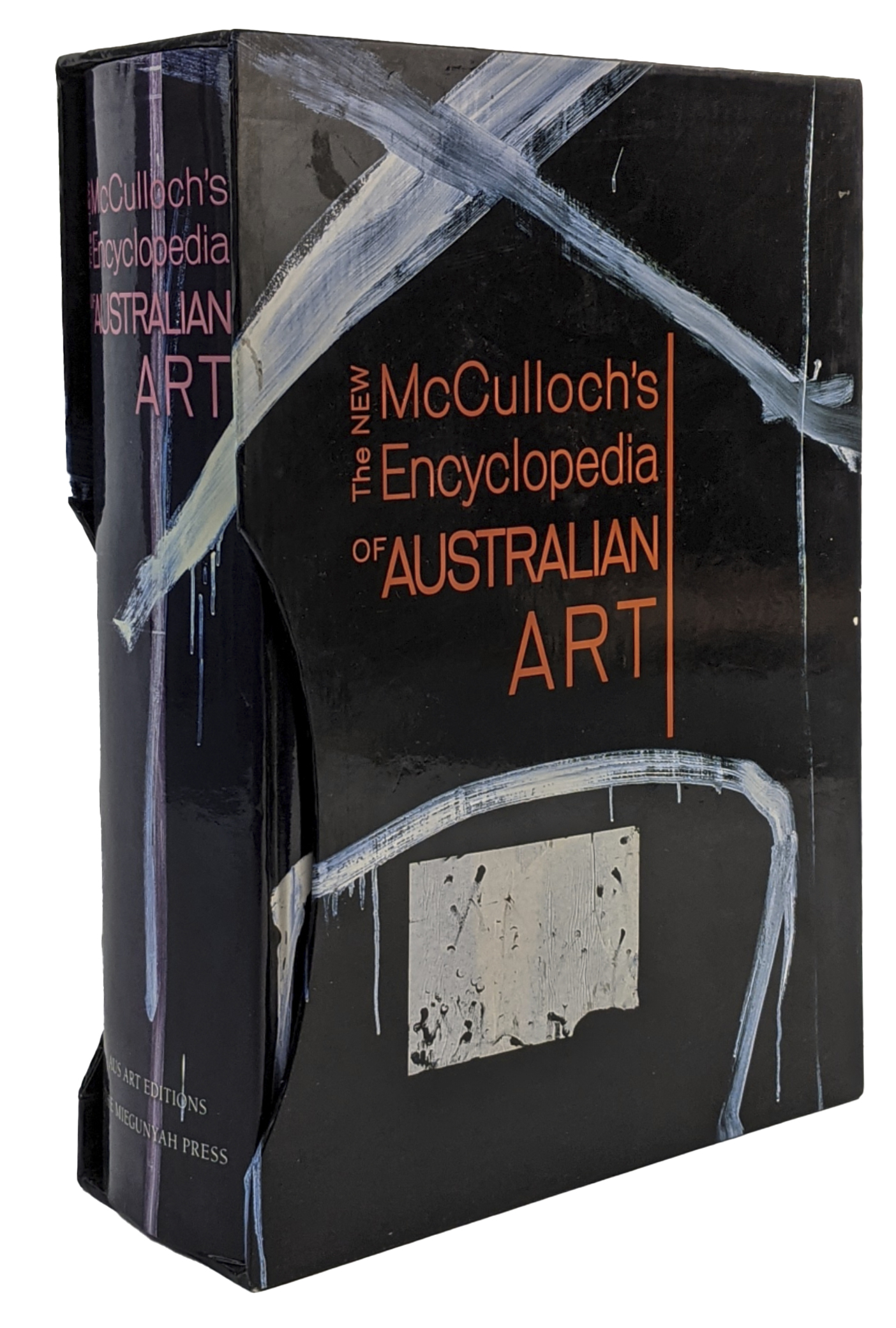

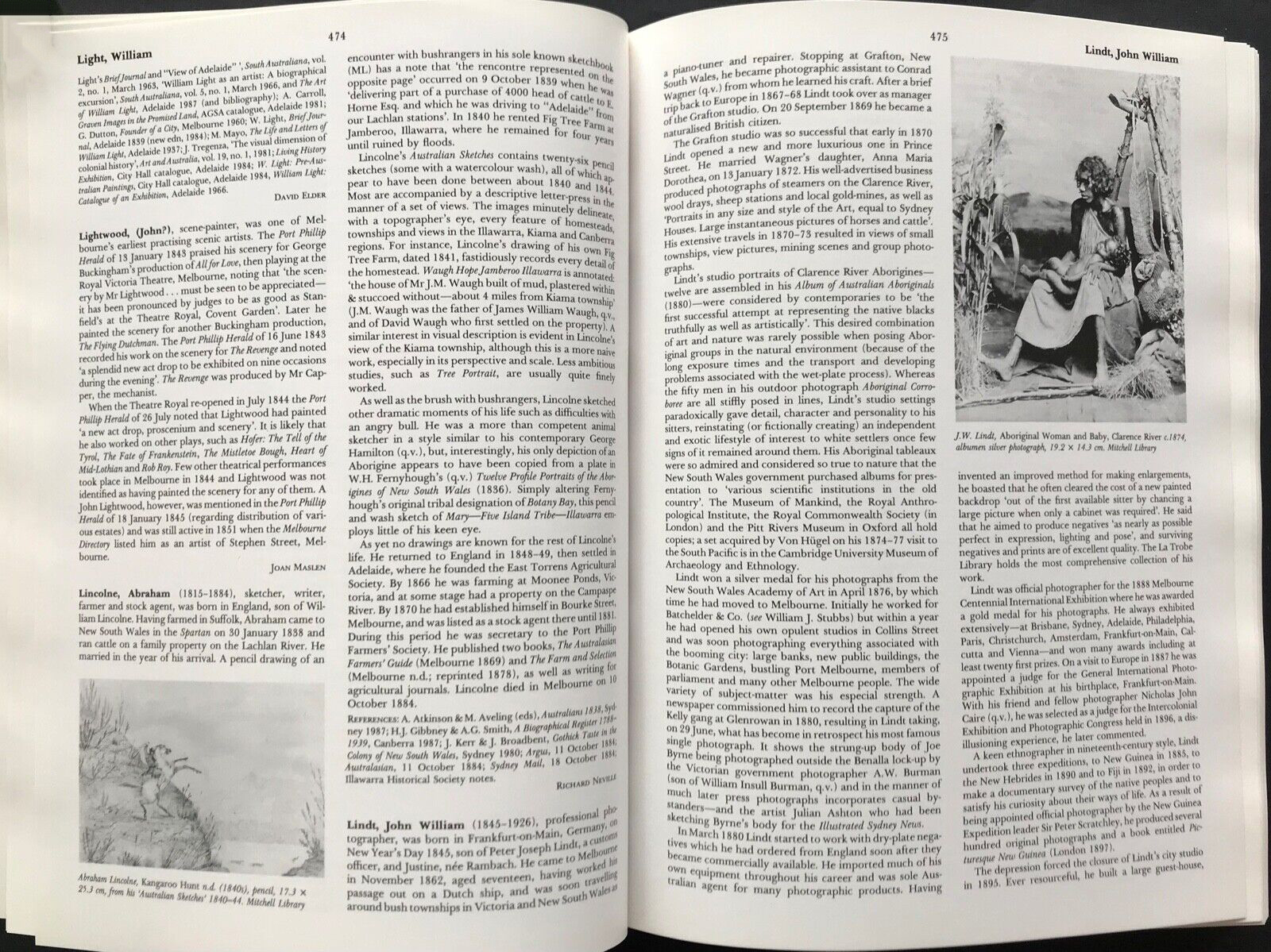

Its origin was in Joan Kerr’s work on the 1992 Dictionary of Australian Artists which with McCulloch’s Encyclopaedia of Australian Art are significant reference works in the field of Australian art history, but differ in their scope. Kerr’s Dictionary covered the colonial period up to 1870, while McCulloch’s Encyclopaedia, first published in 1968 with its latest edition being 18 years old, includes relatively contemporary artists and focuses more on fine artists and painters.

Kerr includes more photographers in a broad definition of “artist”—bringing to light many previously overlooked—with women and Aboriginal artists working in European styles. The latter are given a separate section in McCulloch’s Encyclopaedia which does not have the same explicit mission of covering marginalised artists.

The major difference is the extent of collaboration. The primary authors for the McCulloch volume, which exists only in print, were members of his family, while Kerr’s Dictionary drew on research by 190 contributors including academics, curators, amateurs, and descendants of artists, and it was then digitised, originally in the form of the Dictionary of Australian Artists Online established to bring her research and other Australian art resources online.

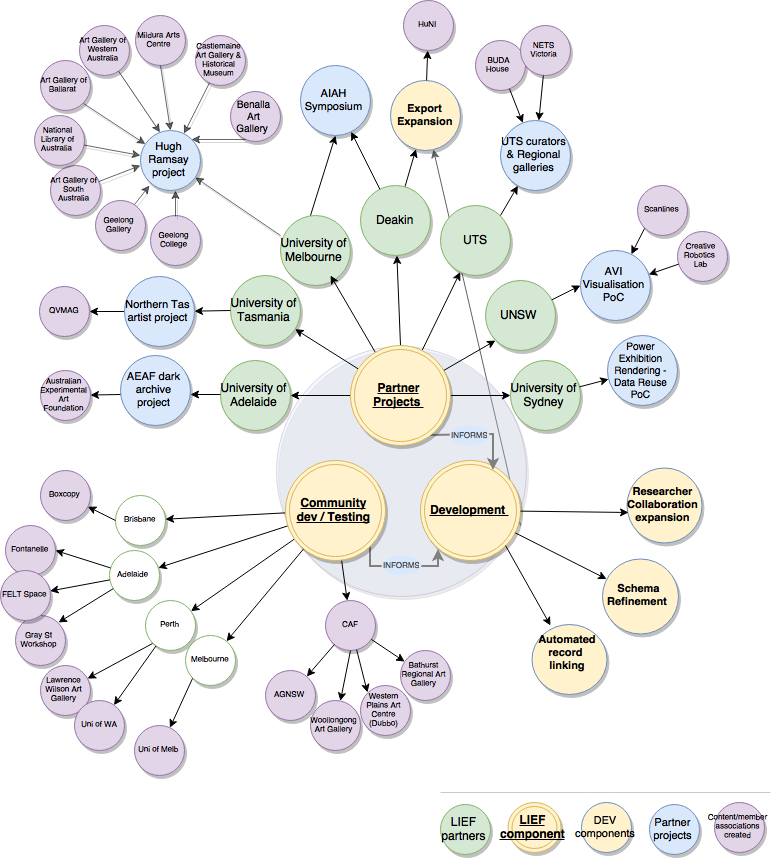

It was rebranded Design and Art Australia Online under the same acronym in 2010 to reflect its broader scope beyond just a dictionary. As an open-access source for information on Australian artists it is integrated with other related databases, using syndicated metadata, for a dynamic and evolving resource that includes both historical and contemporary art.

In this form it is a product of national collaboration involving universities, art galleries, and libraries and encourages contributions from a broad range of scholars and artists, allowing for collaborative entries and original research submissions reviewed by peers, breaking down previous barriers to research, combating patriarchism and parochialism, and encompassing Australian art inclusively. By democratising access to art history it has become an invaluable tool for researchers, students, and the public.

Mendelssohn writes in her April 2014 Conversation article that:

“In 2003, the same year she discovered that she had inoperable cancer, Kerr [who died 22 February 2004] told me that Oxford University Press was not interested in republishing the Dictionary of Australian Artists – even though it was so valuable to collectors that it was selling for up to A$900 a copy.

“The solution was obvious. I suggested that her work, including her latest invaluable research on Australia’s rich tradition of black and white illustration should have a new life online and be free from the whims of old-style publishers. She agreed, but as she knew her time was limited the execution was passed onto others.

“Andrew Wells, the visionary librarian of the University of New South Wales, took the initiative in supporting the concept with resources and contacts. Vivien Johnson, author of Aboriginal artists of the Western Desert, was asked by Kerr to take her place as the initial editor-in-chief to guide the DAAO into being.”

Design and Art Australia Online (DAAO) has emerged as a crucial digital resource for researchers and art enthusiasts, revolutionising access to Australian art history. This collaborative e-Research tool has transformed the landscape of art scholarship in Australia. Today, DAAO serves as an open-source, freely accessible scholarly database, offering biographical data on Australian artists, designers, craftspeople, and curators and its success stems from its collaborative nature; researchers can actively participate by submitting original research and collaborative entries, fostering a community-driven approach to art history documentation. For researchers, DAAO has become an indispensable tool. By digitising and centralising art history resources, it has dismantled previous barriers to research, enabling a more comprehensive understanding of Australian art.

If allowed to continue its evolution and development, with regular updates and expansions, the DAAO’s open access is a boon for researchers, students, and art enthusiasts alike, enriching our understanding of Australia’s artistic heritage and contemporary scene.

DAAO is hugely ambitious and was supported by the University of New South Wales and received funding through ARC Linkage grants in its early stages as it transformed from a standalone database to an integrated resource connected with other related databases, allowing for more dynamic content and searches.

As of 2023 the lead chief investigator was Emeritus Professor Ross Harley, while Olivia Bolton was project manager and governance is by a management committee consisting of representatives of the Universities of Sydney and New South Wales, along with chief investigators. The editorial board includes Mendelssohn and Harley, along with six others.

DAAO exemplifies how digital platforms can democratise access to art history, making it a vital resource for understanding and exploring Australia’s artistic heritage, but the site is now slow to load and sorely needs technical attention, though contributors continue to persevere, enduring log-on glitches and agonising “spinning beachball” standstills in order to upload new or improved information. Pages describing its personnel and mission have not been updated since 2014 and its blog has had no new posts added in nearly 10 years.

How can DAAO’s potentially disastrous loss be avoided?

While the site could be ported elsewhere—to the State Library as some suggest—that would require extensive, and expensive, recoding to accommodate searches via the Library system. A better solution would be to house it in the University of New South Wales library, continuing the association in a research institution context. For Universities bemoaning the idea of capping international student numbers, and even under a Labor government, being expected to be self-funding, this kind of economy seems to make sense, but it defies their own remit to support research that is specific to Australia and made available to the taxpayer.

As always, if any positive outcome is desired, solidarity and an outcry of protest are the ways to get it!