Brian McArdle wasn’t a photographer. At least, not until 1959 when he was 39.

Before and during the COVID lockdowns I catalogued my father’s 500 files of 35mm negatives and about 2,000 transparencies. They are all now safely rehoused in the State Library of Victoria. My next project, after this one on the early years of Prahran, is to address his contribution, through Walkabout magazine, to a renaissance of Australian photography, and indeed to photography as art, a subject on which, during his tenure as the magazine’s editor, he gave a public address to The Australian Journalists’ Association.

My father died in 1968 and his photographs are the only conversation I have had with him in 56 years.

The negative sleeves were packed tightly into two cardboard boxes and the yellow Kodak slide boxes were housed in the battered carcass of an ancient portable electric gramophone player. On each negative sleeve is data for film stock and developer and developer dilution and time, and this records Brian’s settling, after many experiments, on favourite recipes; Tri-X @ 650 ASA in ID11 1:1 for 11min.; FP3 @200 ASA in ID11 1:1 for 8min; Pan F 50 ASA ID11 1:1 for 6 1/2 min.

Each film is catalogued concisely and cross-referenced alphabetically, with entries a mix of his minuscule and rounded journalist’s script and my mother Marie’s no-nonsense, firm and legible nurse’s capital letters. These fragile, faded, ring-bound pages are a keyhole into my parents’ partnership. It was a hard-working, but unequal one, typical of the era, which enlarged my father’s reputation when in fact my mother’s contribution as the layout artist for Walkabout, sales clerk for Brian McArdle Photojournalist‘s business, and assistant photographer, remained uncredited, unknown to any except her children.

These photographs recreate a journey through my childhood and teens; full of adventures and encounters that revolved around my father’s career. How wonderful would it be now to share this voraciously sociable man’s love of the arts and everything Australian, and to appreciate being the butt of his wry, tricky sense of humour. On weekends our house was host to lively visitors in the arts, like photographer Robert B. Goodman who woke us all with raucous whistling (Americans!) way too early in the morning before testing his new Nikonos in the shower. [He was producing a lavish coffee table book titled The Australians (1968), which according to Gael Newton sold 200,000 copies].

We’d traverse Melbourne in our Falcon to visit Albert Tucker in Warrandyte, or Mirka Mora (…”your fahzere eesze most intelligent man I ‘ave met”) and husband Georges and their boys on the beach at Aspendale, drive to Adelaide or Canberra or Sydney where Brian would chase stories for the magazine. A roadside encounter with a koala on a fence would turn into an hour-long session posing obediently for pictures; tedious, but rewarded by the sight of ourselves printed in Walkabout. Every holiday held an ulterior motive!

To see through my father’s eye is to have his affection for me affirmed, however distant it has become through time now, and remote at the time because of his dedication to his work, and through his early death (a heart attack caused by his alcoholism) which my teenage self regarded as a ‘betrayal’. My respect for his love for this medium realises, at last, my love of him. However much estranged do parts of life become, photography has the power to restore.

Brian—James Brian De Largie McArdle—born in Hawthorn on 25 July 1920, was a journalist, following in the steps of his father James Lawrence McArdle, who worked on the Argus, The Age, and Herald in Melbourne, and the Morning Herald, and the Catholic Advocate (Brisbane). Brian attended Xavier College. His grandfather on his mothers’ side, from whom he took a middle name, in the Scottish tradition, from his mother, was Hugh De Largie, (1859–1947) Senator for Western Australia, 1901–23 in the various manifestations of the Labor Party, the National Labour Party and Nationalist Party.

Brian served from age 20 in WW2, when he was trained in central Australia and Darwin, promoted to Sergeant and paymaster, and was wounded in New Guinea.

Post-war, he lived at the family home in Elwood, and worked in the Naval Historical Research Section, Naval Intelligence Division, Victoria Barracks, Melbourne. S.C.I. to c.1948. on a section of the Official History of the Royal Australian Navy, corresponding with Billy Hughes on his dealings with the Commonwealth Shipping Line. Meanwhile he studied Arts/Law at Melbourne University under a returned serviceman scheme but did not finish, but started as a journalist on the Geelong Advertiser.

From November 1953 he replaced Bruce Grant as film critic on The Age and with his own column “Spotlight on Films” in its ‘companion’ weekly, The Leader, he personally favoured European films over Hollywood productions, as he does in the cutting I have below.

In it, he admires Roger Hubert‘s “striking, low-key photography” under Marcel Carné‘s direction, but gives short shrift, beneath the heading “Sickly Crime Film,” to Hollywood’s Six Bridges to Cross. That is how he learned photography, from looking at film, telling me that “to do something well, you need to see, and know, the difference between the great, and the worst, and so develop your discernment.”

While his family was still very young, like so many Australian’s of the era, he moved us all in March 1956 to London, away from our idylic, then still-unspoiled, bay-side Beaumaris with its sandy tracks to the beach among ti-trees, and into a flat in the far left rear corner of this forbidding Victorian pile in Kilburn, its plaster still crumbling from the shock of nearby bomb-blasts during WW2, and the lawns of this c.1906 photograph long gone to seed and surrounded by blighted box-thorn bushes.

It was from its window that, at the age of five or six, I took my first photograph, of the garage in the street below, with my father’s Agfa Silette bought for £9.18s (a value of $A534.08 today) in Newhaven after arrival in the UK by ferry from Dieppe.

The object of my interest was the vertical text of the sign G A R A G E which I was proud to be able to read.

Brian’s own photographing accelerated. Aside from the tourist shots for which he’d purchased the camera, he took it into work and attempted to capture the busy atmosphere there in the thick of the Suez crisis, but the limitations of the Retinette fail him…

…though he captures a fine likeness of the ebullient Des Hennessy whose revival of the Port Phillip Gazette as quarterly had failed after its Autumn 1956 issue, when Fennessy left for the UK and in 1957 was working with Brian in Fleet Street, before moving on to edit the Ashanti Times in Uganda until 1960.

Several posts here over the last year have dealt with the period of the 1960s and 1970s and the reemergence/revival of photography as fine art in Australia, but playing a strong role in that impetus was the picture magazine. Brian was driving part of it.

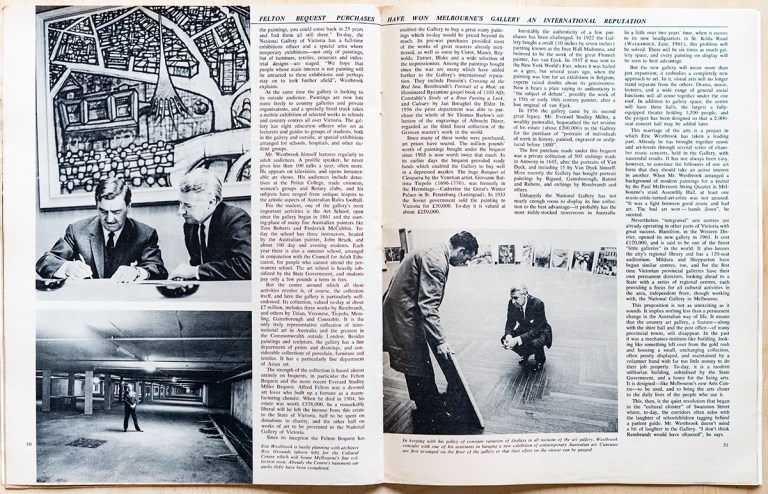

It is 1965, and Brian is getting preview of the Gallery’s new quarters for a story “Marrying Melbourne’s Arts, on the new Cultural Centre designed by architect Roy Grounds. He photographs Westbrook in his office in the 100-year old State Library. Made in lighting conditions similar to that of his Radio Australia snap, it shows clearly that his technique has been refined by his constant shooting at the rate of a roll every 3 days on average; by the rigor of shooting for the national magazine Walkabout that was, under his editorship from 1960, welcoming imagery from the best of Australia’s photojournalists; and by his familiarity with the visual narrative of good cinema.

Westbrook, who was the first Director not to have been an Australian artist, came to Australia via directorships in Yorkshire and Auckland, and he brought a less provincial, more inclusive attitude, including a commitment to the collection of photography;

“The National Gallery of Victoria is in the forefront in recognising that in whatever field photography is seen as an invaluable service to mankind, its service to art and its potential as an art form can no longer be ignored […] The camera is supreme when its analytical eye is directed like some powerful beam of light onto the strength, the frailties, the involvements of humanity as in photojournalism.” [NGV pamphlet 1967]

In April 1966 The Photographer’s Eye, compiled by John Szarkowski, Director, Department of Photography, Museum of Modern Art was brought to the National Gallery of Victoria after which it was shown as part of the 1968 Festival of Perth, then in Shepparton, Ballarat, Bendigo, Mildura, Castlemaine, Geelong, Sydney, Newcastle and Adelaide and afterwards in New Zealand in 1967, where it was as influential as The Family of Man (not shown in NZ) had been on Australian photographers.

As Director Westbrook persuaded the Trustees that a Photography Department should be established and in November 1966, Albert Brown (1931–2017), of Group M, was appointed as an honorary photographic consultant. The association with the National Gallery of Victoria proved useful for Brown who was able to obtain promises for work from the Bibliotheque Nationale, Standard Oil, University of Texas George Eastman House, the State Historical Society of Wisconsin, the Mitchell Library and the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Brown’s efforts influenced Eric’s thinking. He was well aware of their work and in November 1966, wrote thanking them for the interesting exhibition from the Gernsheim Collection.

Supported by Professor Allan Martin, Professor M. Marwick and Professor Geoffrey Blainey, Eric Westbrook was able to persuade his trustees in April 1967, to establish a Department of Photography. Soon after, prior to moving from the Swanston Street site, Albert Brown arranged for work from the Museum of Modern Art to be exhibited.

The first solo exhibition of photography, shown in 1968 just before the NGV moved from the old gallery shared with the State Library and Museum, was of portraits by Mark Strizic. One included was of the British-born director of the NGV, Eric Westbrook. Unfortunately that picture is not online.

Hi James

I hope you are well 🙂

But what is the password please!

Kindest regards,

Marcus

Art Blart ( https://artblart.com/ )

Dr Marcus Bunyan* Image Maker, independent writer, curator and researcher

MB website ( https://marcusbunyan.com/ )

Email: bunyanth@netspace.net.au ( http://netspace.net.au )

Mobile: 0425828793

LikeLike

Hi Marcus – I’ve removed the password on this post. Cheers, James

LikeLike