On 20 May I was one of the presenters at a photography forum at Castlemaine Art Museum organised by artist Jane Brown, curator Jenny Long and director Naomi Cass. My paper incorporated research I had written up in this blog. Here is a text version of the talk…

On 20 May I was one of the presenters at a photography forum at Castlemaine Art Museum organised by artist Jane Brown, curator Jenny Long and director Naomi Cass. My paper incorporated research I had written up in this blog. Here is a text version of the talk…

Come with me into the dark, and into the night. Put out your torch, and let your eyes accustom…there’s always light in the bush and besides—the beam of a torch is like a telephoto lens, the preferred optic of the timid, anti-social voyeur.

Instead, use your senses as around you and beyond the crescent moon makes lace of the trees. The clay path, rough under your feet, reflects the glow of the clouds and sparks as you kick its stones, startling unseen kangaroos which flee with a whiplash crack of their tendons. Let the grevillea, bush-peas and mint-bush guide your step as they brush your legs and release their herbal scents.

Adopt the wide-angle view of a Super-Angulon, even a Fisheye lens…one that makes a picture into which we can climb, to peer around and into its corners; an image to be in, entangled in its weft, its warped curves the very fabric, the cloak, of a reality that the great photograph wraps about us, one that takes us in, where the photographer was.

In another dark space, you’ll find Jane Brown, Harry Nankin, Ellie Young lifting the slimy, slippery print from the developer, cauterising it in acetic acid, then plunging it into the glacial depths of the fixer.

Imagine carrying out such a procedure – coating a fragile glass plate with syrupy collodion emulsion—in a blacked-out tent or wagon—then stepping into this tumult of harsh sunlight, mud and gold-crazed miners;

Both returned to Australia in 1857—French adventurer Antoine Fauchery and British geologist Richard Daintree—and formed an unlikely partnership in Collins Street, later the ‘Paris End,’ the haunt of J.W. Lindt, Nicholas Caire, Ruth Hollick, Mark Strizic, Athol Shmith, Wolfgang Sievers…think of Barry Humphries in “the Melbourne end of the Champs Élysées.” They were in Chewton, in Forest Creek, in 1858, and I believe it was Fauchery — the inspiration for Marcel in La Boheme and author of Lettres d’un miner en Australie that attracted Mirka Mora’s migration to Melbourne — who has devised this tableau.

Produced in the album Sun Pictures of Victoria in ten instalments, The Argus advertised it in 1858 as being made with “the stereomonoscope, by means of which the objects exhibited in a sun picture, of any size, assume solidity and relief to the eye of the spectator.”

That invention, only very obliquely to do with with Jane Brown’s graphoscope, was determined in 1955 by our first historian of photography Jack Cato to be the 1840 Petzval portrait lens—its extreme curvature of field produced such volumetric bokeh. Such a spirited photograph!

We are graced in Castlemaine with a newspaper that reaches right back into 1854 and in it we can discover our earliest commercial photographers Jackson and Ostler operating from a bookshop in Market Square, who guaranteed “A correct likeness, or no charge.”

While Daintree and Fauchery were photographing the retreat of the Dja Dja Wurrung to Mount Franklin, Frederick Henry Coldrey (1827-1889) and Alfred Fenton set up a collodion studio adjoining the Horse Bazaar on the Main Road, Ballarat and developed the Pannotype a “new improvement in photography,” a collodion negative print on black leather, convenient for posting, but too late given the advent of the carte de visite.

After the death in March 1859 of his first son aged 4, a robbery, floods, and the departure of Fenton from the partnership, Coldrey was declared insolvent in 1860, due to debts he could not clear through the sale of his equipment and possessions.

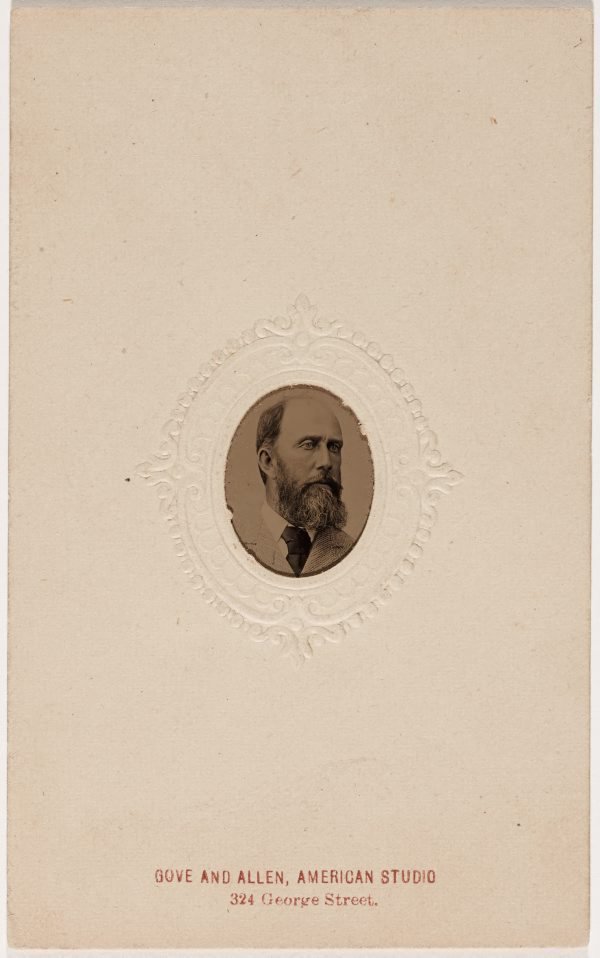

He set out as an itinerant photographer across the state from Avoca to Jerilderie until he joined Charles Wherrett here in Castlemaine as an ‘operator’ at a studio known for its ‘spirit photographs’, before in 1874 taking up management of Kerr’s Portrait Rooms a few doors away in the freshly constructed George Clark Building where he made a living from cartes-de-visite.

He set out as an itinerant photographer across the state from Avoca to Jerilderie until he joined Charles Wherrett here in Castlemaine as an ‘operator’ at a studio known for its ‘spirit photographs’, before in 1874 taking up management of Kerr’s Portrait Rooms a few doors away in the freshly constructed George Clark Building where he made a living from cartes-de-visite.

In the 1860s had come the carte de visite considered now by by researchers as an early instance of ‘social media’. Perceptively Andrew Winter wrote in 1862 that:

“The commercial value of the human face was never tested to such an extent as it is at the present moment in these handy photographs. No man, or woman either, knows but some accident may elevate them to the position of hero of the hour and send up the value their countenances to a degree they never dreamed of.”

Shortly after producing the composite of the Pioneers and Old Residents Association Coldrey complained to the October 1881 Borough Council meeting of “a photographer’s tent being erected in the Market Reserve…as an injustice to him, as he pays heavy rent and taxes which disable him from competing against person paying a small rent for a short time.”

He was facing the arrival of a franchisee W. Roy Millar who had an American GEM franchise. These tiny portrait photographs were anywhere from 2 cm to 2.5 cm wide and 3 cm high produced in a multi-lens camera with repeating back making multiple exposures on a single photographic plate. Proprietary patent cards to hold them and that would fit carte-de-visite albums were marketed for them and special ‘gem’ albums also produced. In 1873 franchises were opened in Melbourne and Ballarat. The Sandhurst (Bendigo) studio closed in 1882, but Millar was one of many ‘flying’ itinerant operators in the Western Australian goldfields 1895-1901.

He was facing the arrival of a franchisee W. Roy Millar who had an American GEM franchise. These tiny portrait photographs were anywhere from 2 cm to 2.5 cm wide and 3 cm high produced in a multi-lens camera with repeating back making multiple exposures on a single photographic plate. Proprietary patent cards to hold them and that would fit carte-de-visite albums were marketed for them and special ‘gem’ albums also produced. In 1873 franchises were opened in Melbourne and Ballarat. The Sandhurst (Bendigo) studio closed in 1882, but Millar was one of many ‘flying’ itinerant operators in the Western Australian goldfields 1895-1901.

Five days after Millar’s letter, an advertisement appeared in The Age, Melbourne:

“GEM Camera, wanted to Buy. State price, F. Coldrey, Post Office Portrait-rooms, Castlemaine”

Coldrey Street, on the corner of which the family lived, is a short lane that runs between the northern stretches of Bowden and Farnsworth streets, and is named for him.

Trained in photography by a Melbourne firm, like Coldrey and Millar, Adolphus Verey traveled Victoria as an itinerant photographer before also renting Wherret’s studio. Verey warrants 3,000 entries in the Mount Alexander Mail so clearly he made a mark on the town beside that which remains on the site of Wherrett’s studio which in 1907 he rebuilt with 2 storeys as reported on its reopening, attended by local M.L.A. Harry Lawson

The period in which he was working, at first with his brother, was as transformative as that wrought by the carte de visite. George Eastman released the Kodak in 1888, and the Brownie in 1900, industrialising, commercialising, and popularising photography. Verey, who died in the year after Eastman, profited handsomely nevertheless.

I suspect that this 1884 cabinet print of the Botanical Gardens may be the product of brother Frederick. Listing alarmingly starboard the 1884 view is photo-bombed by a man standing obstinately at centre, arms folded, and his son with his penny-farthing beside him, in the then 20-year old Gardens, first developed the year Verey was born. The 1878 imported Italian fountain can be seen (left rear). Brother Frederick retreated to the family sawmill in Daylesford in 1889.

I suspect that this 1884 cabinet print of the Botanical Gardens may be the product of brother Frederick. Listing alarmingly starboard the 1884 view is photo-bombed by a man standing obstinately at centre, arms folded, and his son with his penny-farthing beside him, in the then 20-year old Gardens, first developed the year Verey was born. The 1878 imported Italian fountain can be seen (left rear). Brother Frederick retreated to the family sawmill in Daylesford in 1889.

This by Robert Vere Scott made c.1905 from roughly the same angle, is a superior composition despite the challenges of the panorama format.

Gael Newton as determined that the camera used is the Kodak Panoram.

Though there is no record of it, Scott and Verey must have encountered each other, and one panorama shows the roof of the studio prior to its reconstruction. Incidentally, and of relevance to their chosen medium, the names Vere and Verey derive from verus, true, via Ver, a town in Normandy.

The rebranding of Scott’s panoramas with the Verey name raises questions because of the way that Scott’s signature, which he wrote on his negatives, is scratched out.

Panoramic views of course were nothing new and in Australia had been produced since the late 1840s— examples being by the genius polymath William Stanley Jevons and a panorama of Sydney Harbour, a camera lucida drawing by Louisa Anne Meredith.

Mach distinguishes with this diagram the difference between physiological (specifically visual) and geometrical space and the way that knowledge is constructed rather than received.

Tara Gilbee’s tin can pinhole cameras as an analogue for the human eye seems to verify that as we examine it.

Geoffrey Batchen frames photography’s origin a desire as much as technology, a deep cultural need for what was to become photography. The same might be said for the panorama; after all…we got Google Street View

Friedrich (von) Martens painted panoramas anticipate those the made on curved daguerreotype plates (n the same principle as Gilbee’s), while Henry Fox Talbot uses his calotype process to piece together this scene of activity at Reading, which when digitally joined shows, by the passage of shadows, how long the photography took.

Melvin Vaniman was an American adventurer who was was in Adelaide in 1904 and who used the formidable Kodak Cirkut for such images as his 1903 Panorama of the intersection of Collins and Queen Streets, Melbourne as did Scott for a c.1905 view of the corner of Collins and Elizabeth Street.

From 1903 to 1907 Vere Scott was based at Port Pirie but traveled the east coast to make his panoramas.

Scott’s intentions unlike Vaniman’s are not merely topographic but artistic; his two views of the Botanical Gardens appear atmospherically moonlit.

By turning the camera on its side for one Scott encourages a sense of spatial immersion carefully organised around divisions of thirds which arrest our eyes on their transit from the wind-battered trunks into the clouded reaches of the moon, the passage of the Creek into the distance, and into the depths of the water, seen probably from the bridge at the top of the Gardens; some clouds painted into the negative, like his signature.

He embraced the Pictorialist photography movement, advanced in Adelaide in these years due largely to Adelaide-born art photographer John Kauffmann (12 years Scott’s senior), who spent ten years in Europe where he experienced Pictorialist photography, bringing these ideas back to Adelaide in 1897. By 1907 Scott was regarded as Kauffman’s equal, as evidenced by their equal billing and high profile in the Christmas number of the Adelaide newspaper The Observer.

Constant Puyo also used the panoramic camera for Pictorialist effects (laundresses seem to be a theme attractive to photographers…is it all that running water in the darkroom?). He also adopted the vertical format.

Via the fascination of the Impressionists for Japanese art, and particularly with the 17th century pillar painting or Hashira-e, Pictorialists in Europe and America adopted this format for its aesthetic effect, one picked up in Art Nouveau.

Witness his ‘moonlit’ style, a nocturne like Kauffmann’s later work of that Whisterian title, in Scott’s Ben Buckler at the NGA

…actually an underexposed negative printed heavily to look nocturnal, as can be confirmed from the sharpness and lack of motion blur of water that would be impossible to achieve with the long exposures required under the light of the moon.

Castlemaine Art Museum is fortunate in possessing in the Moonlit Garden what may be a pinnacle of Scott’s more artistic work and a rare technical response to Pictorialism. It is most certainly early, before he started using the ‘Cirkut’ camera, because that could not be operated on its side to produce a tall image.

Around 1907 Vere Scott moved to Kalgoorlie and contributed imagery of the town to The Lone Hand, and E.J.Brady’s 1918 book Australia Unlimited. But he was soon travelling again, to New Zealand 1910–14, back to Brisbane in 1915, then in 1916 Scott migrated with his wife and children to California and set up a studio in San Francisco in 1918, and was producing nautical and panoramic views well into the 1930s. His WW2 draft registration card of April 1942 lists him as a Boston “scenic photographer.” He died in 1944.

My intention here has been to emphasise the nocturne in Jane Brown’s photograms and her low-key lensed imagery, and to reveal a metaphorical panorama there that extends from the work to enwrap the viewer.

Frédéric Chopin: “They are not mere nocturnal reveries… but rather the voice of the evening bell… that sings to us of restful thoughts…” (Letter to Julian Fontana, 1841)

A comprehensive and entertaining summary of an intense afternoon of talks.

The speakers were passionate and could have elaborated more on their particular expertise if time allowed.

The range of topics was extraordinary.

LikeLike