All eyes are on Monash Gallery of Art and its $30,000 William and Winifred Bowness Photography Prize. But is the winner a photographer?

All eyes are on Monash Gallery of Art and its $30,000 William and Winifred Bowness Photography Prize. But is the winner a photographer?

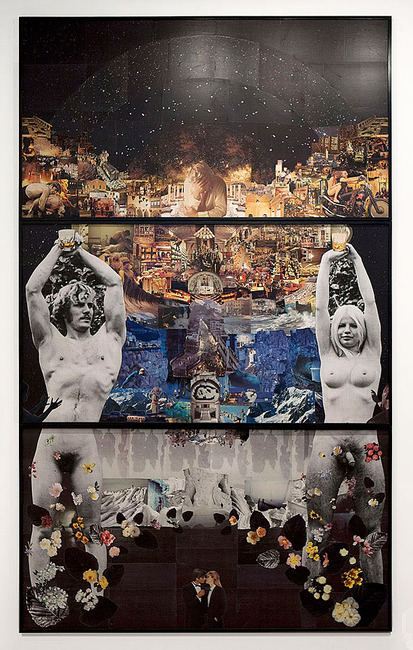

Now having run 16 years, the latest Bowness has been won by Lillian O’Neil (*1985). Judges were Del Kathryn Barton (artist), Anouska Phizacklea (Director Monash Gallery of Art) and Karen Quinlan AM (Director National Portrait Gallery, Canberra). O’Neil’s win follows Christian Thompson‘s last year also with a large collage 2.5m square, as is his entry this year, and while hers is slightly smaller at 1.8m it is typical of the scale at which she works.

Sherrie Levine (*1947) declared in the magazine Style (March 1982) that “a picture is a tissue of quotations” and British photomontagist John Goto (*1949) once remarked, “I feel there are enough photographs in the world, and I don’t particularly want to add to the mountain.” A generation later, O’Neil also doesn’t take her own pictures. She sources them from archival material in libraries and second-hand bookshops.

As a result, in her enlargements of her collages from them, they bear the texture of photomechanical reproduction; the halftone dot-screen, and also show the seams where sheets have been joined. While most are black and white, they are nevertheless not monochrome, but subtly carry tones tinted with the colour of the ink used in printing them.

Natasha Bullock in reviewing O’Neil’s earlier work in Photofile‘s 2013-14 issue, identifies a ‘retro’ feel in her Attack of the Romance(2012), and a sense of humour in its figures’ flaunting of their swapped genitals; manic, surrealist ‘exquisite corpse’ fun. That might be traced back to the artist’s involvement from age 22 in the Melbourne-based collaborative group, Safari Team. They formed whilst its three members (the others being Blaine Cooper and Jon Oldmeadow) were Fine Art undergraduates at Monash University, producing multidisciplinary work incorporating video, installation, performance, collage, drawing and sculpture. Their delightful Molto Morte (2008) was hailed as one of the highlights of the 2008 Next Wave Festival. She left them three years later, after Next Wave 2010, to make ever more ambitious montage work on her own, exhibiting it frequently.

Anna Sutton in Broadsheet, October 2013, dates the appropriated images for Attack as “from books printed in the years 1940 to 1999,” and quotes O’Neil’s rather disturbing millennial generation take on pre-internet, printed, pictures;

“All the images I collect are quickly becoming obsolete so I would like my work to act as shrines for this fading aesthetic”

Also in 2013, she was included in In the Cut – collage as idea, curated by Hannah Mathews, Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne.

In 2014, O’Neil received an Australian Postgraduate Award to complete a Master of Fine Art at Sydney College of the Arts, and now a PhD, supervised by artist, Mikala Dwyer whose eorðcræft geometry O’Neil may have experienced as an organising principle in work that followed, on which Louise Martin-Chew, comments in an extended review in Vault: Australasian Art &Culture (Feb/Apr 2019);

The original materials are strenuously reinterpreted by images that appear to conjure the tenor of the changeable and fractured times in which we live, their disjunctive stimuli and disconnected realities. Motifs that recur include symmetrical and tightly constructed images using geometric shapes and planes, fractures and facets…

Martin-Chew echoes Steven Miller in his 2017 exhibition text for Escape Velocity, at The Commercial Gallery, Sydney;

O’Neil’s collages, whilst often whimsical and full of human warmth, look out upon the world, dissecting and questioning, through a distinctly 21st-century, post-9/11 prism.

Prismatic they are. In Drawing to a close we experience a compelling vortical one-point perspective, to which the title might refer, assembled from pieces of a dozen images from separate sources yet which exactly fit the orthogonal lines to create a believable scene in depth but terminate at a vanishing point in open sky within a barely-glimpsed garden.

We imagine O’Neil searching through thousands of images, remembering not only their coincident shapes but also the subtleties of viewpoint to create this snail’s-eye standpoint. You would be at great pains to rediscover these obscure documents. A fragment of a news photo, perhaps, of earthquake-fissured asphalt forms the foreground; immediately striking but in contrast to the lying male figure who is so relaxed as to permit a pair of disembodied arms (perhaps those of an anonymous chiropractor, or a modern ballet dancer) to lift his waist from the floor. A picture of an arched window reflected in a pool forms the top left to corner of the assemblage, but it had to be turned upside down to work.

We forgive the fact that window shadows on the right, which feasibly come from a casement like that opposite, run counter to the overall perspective as tiles under the man’s legs balance the movement in a chevron at the point of which lies the man’s passive hand. Even the top lighting of his nude figure is consistent between the two portions that make him up. The placement of the portal, a wormhole, that hints at an unseen universe extending above his, is perfect and matches the slant of the climbing loops to the right. Elsewhere, where not directly serving a spatial purpose, lines and planes align or meet in a countercharge of tone superimposing a set of rectangles that seem to slide across the image like a tile puzzle, a reminder of the construction process.

Some may read into O’Neil’s image reference to the ‘canons’ of art, perhaps the archetype of the Deposition, or of the entombed, supine form of Christ such as that in Hans Holbein the Younger‘s painting The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb of 1520–22, likewise depicted from an extreme viewpoint. The painstaking and necessarily intuitive and reactive process of photomontage from found materials is open-ended, however, and would seem to militate against such an express intention. The conspicuous ‘stitching’ of the image construction invites a materialist reading, though not an hermetic one. Interpretation of the product is left enigmatic, and its haptic qualities invite the viewer’s rapport with process; that is integral to its affect.

The component photographs, and their photographers’ own intentions also remain embedded. Against her sense of pre-Internet material being “now generally obsolete,” it is a relief to read O’Neil’s acknowledgment of the photographers of the images she collects, and that they are not forgotten but are “shimmering below the surface,” inspiring her work.

O’Neil lives with her partner on a rural block not far from her childhood home Torquay, on Victoria’s surf coast, where her father kept a darkroom. Since her usual sources of material such as the State Library were closed during lockdown, she has been traveling 30km to Geelong to work at Platform art space in an old courthouse opposite the Geelong Art Gallery which showed her recently commissioned mural Evening in October this year. Her recent solo exhibitions include include Artspace, Sydney, Ideas Platform (2019), Youkobo Art Space, Tokyo (2019) and Tertium Quid, The Commercial, Sydney (2018); with group exhibitions that include The Body Electric, curated by Shaun Lakin at the National Gallery of Australia (2020); and the National Photography Prize, Murray Art Museum Albury (2020). She is represented by The Commercial, Sydney from which the National Gallery of Australia and Art Gallery of New South Wales each made purchases from her 2017 exhibition.

Unbelievable!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Taken me a long time to find the time to read this properly James. It is a great piece. Thanks.

LikeLiked by 1 person