January 31: To delve into the meaning and intention of a photograph from a distance of nearly 150 years is an uncertain exercise.

January 31: To delve into the meaning and intention of a photograph from a distance of nearly 150 years is an uncertain exercise.

Paul Heinrich Matthias Foelsche died, after months of crippling pain, on this date in 1914 in Darwin, Australia. Born in Germany in 1831, he served in the Hussar Regiment before migrating to South Australia at age 25, where in November 1856 he became a ‘trooper’, as the mounted police in the British colony were then known.

While at Strathalbyn he joined the Masonic Lodge, soon becoming Grand Master, and his contacts through it may account for his sudden promotion by Lord Kintore, the Governor of South Australia, to Sub-Inspector in charge of the newly-formed Northern Territory Mounted Police in December 1869. He journeyed there in January 1870 on the steamship Kohinoor, to spend his remaining years in the Territory apart from brief visits to Adelaide in 1884 and China in 1897.

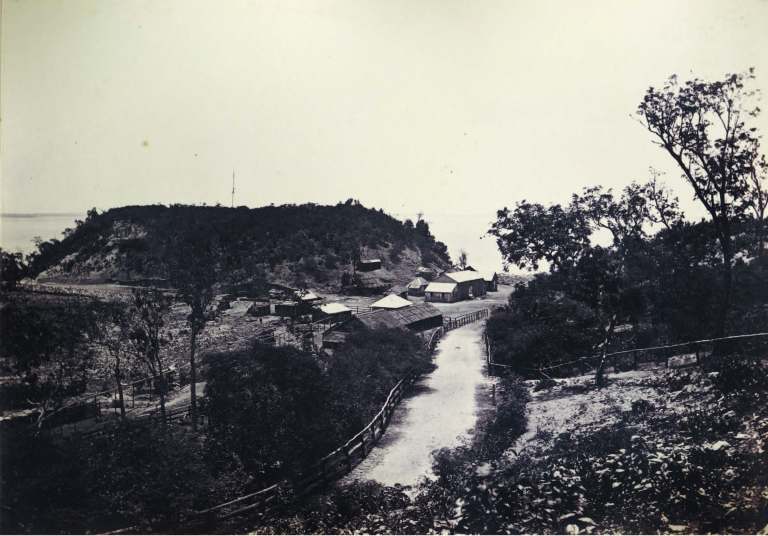

South Australia had accessioned its ‘Northern Territory’ in the 1860s to expand its pastoral holdings served by a northern port. So recently opened up, Palmerston (Darwin) had no police station and Foelsche and his six troopers had to build their own.

Captain Samuel Sweet (1825–1886), part-time commercial photographer and master of the colony’s supply ship, undertook photographic documentation as part of the 1869 survey party’s responsibilities, and it was soon realised that such pictures could be used to attract investors and migrants to the region, and thus Sweet’s views of the infrastructure and the more striking landscape features of the new colony were widely circulated in Adelaide and London.

After Sweet left the colony in 1872, Foelsche voluntarily took over his role in supplying promotional photographs. He was an enthusiastic and expert photographer and documented some of the earliest developments in the new town. They were exhibited at a succession of international exhibitions and earned him a “magnificent gold hunting watch and a signed, enlarged photograph from the Kaiser.” The image above of Mitchell Street, looking south was made to record the new cross-continent telegraph line, and also shows Foelsche’s house and shed at left. What is extraordinary about this wet-plate photograph is the rare clarity of the clouds, given the blue sensitivity of the emulsion.

He made a series of group and individual portraits of Larrakia, Woolna (Djerimanga), Iwaidja and other Aboriginal groups of the Top End. From the mid-1870s he began collecting ethnographic material, supplying International Exhibitions and the South Australian Museum, with documented artefacts.

A biography by photohistorian Robert James ‘Bob’ Noye (1932–2002) at the Australian Dictionary of Biography is glowing about Foesche’s career, and records that;

Police Commissioner George Hamilton (1812-1883) considered him one of the most capable men in the police force, and Lord Kintore, governor of South Australia, described him as intelligent and efficient.

Since 1962, the members of Masonic ‘Lodge Foelsche’ have conducted annual graveside services to commemorate him and as recently as 2013 he was honoured with a police Guard of Honour (above).

These tributes should be seen in the context of the November 2009 article in The Monthly, titled The Brutal Truth: What happened in the gulf country by historian Tony Roberts (*1945) who catalogues the ill-treatment and massacres inflicted on the indigenous population;

At least 600 men, women, children and babies, or about one-sixth of the population, were killed in the Gulf Country to 1910 [that is, over the entire period of Foelsche’s administration]. The death toll could easily be as high as seven or eight hundred. Yet, no one was charged with these murders. By contrast, there were 20 white deaths, and not a single white woman or child was harmed in any way.

These facts stand on one side of the ‘history wars’, an ongoing dispute over a denial by a substantial portion of Australia’s population that massacres took place, despite substantial evidence that they may have been under-estimated, and who side with conservative ex-Prime Minister John Howard who argued in a 1996 Sir Robert Menzies Lecture that the “balance sheet of Australian history” had come to be “misrepresented” by a “black armband” view of our history (read ‘political correctness’). Such views would seem to have support in the Australian Dictionary of Biography’s hagiography of Foelsche;

In pursuit of his police duties Foelsche was unrelenting and displayed exceptional energy and courage when he led the search for native murderers. His cunning stratagems invariably led to the apprehension of suspects.

But Roberts adds damning detail about Foelsche’s disproportionate response to the 30 June 1875 incident at the Roper River, when a telegraph worker from Daly Waters had been killed, and his two mates badly wounded, probably by Mangarrayi men;

Foelsche issued these cryptic, but sinister, instructions: “I cannot give you orders to shoot all natives you come across, but circumstances may occur for which I cannot provide definite instructions.” Roper River blacks had to be “punished”. Foelsche wanted to go with them, but it was a large party, he said, with “too many tale-tellers”. He boasted in a letter to a friend, John Lewis, that he had sent his second-in-command, Corporal George Montagu, down to the Roper to “have a picnic with the natives”. Even the normally enthusiastic Northern Territory Times was sickened by “the indiscriminate ‘hunting’ of the natives there”, adding “there ought to be a show of reason in the measure of vengeance dealt out to them.”

Gordon Reid (*1929) in a 1990 book taking its title from Foelsche’s euphemism “a picnic with the natives” (A Picnic with the Natives: Aboriginal-European relations in the Northern Territory to 1910), quotes from another personal letter:

Of course you have seen all about our Nigger Hunt in the papers. … I left it to Stretton, and I could not have done better than he did so I am satisfied and so is the public here.

Roberts therefore quite understandably condemned a one-sided exhibition Paul Foelsche: A Life’s Work (1831-1914) held in the Northern Territory Library, Parliament House, Darwin, from 28 January 2014 to 23 March 2014, saying;

Foelsch masterminded and orchestrated massacres of innocent Aboriginal people in the northern half of the Territory for 30 years. If he were alive today, Paul Foelsche would be prosecuted by the United Nations for crimes against humanity.

Northern Territory Attorney-General John Elferink, since sacked from his post as Corrections Minister over the mistreatment of teenage aboriginal prisoners, hastily rose to Foelsche’s defence;

What I do know is that the original police commissioner, Inspector Foelsche, for the Northern Territory of South Australia, did a lot of good in the community. I will leave the history wars for the history war buffs.

I’m interested in a particular photograph that Foelsche took in Darwin in the Northern Territory.

The State Library of South Australia which holds the negative of this image captions it;

A reconstruction by Foelsche of the shooting of escaped Chinese prisoner Ah Kim during a police attempt to capture him in May 1875. Foelsche painted the puff of smoke from the policeman’s gun onto the glass plate. The falling figure of Ah Kim is represented by a stuffed dummy. Ah Kim was one of the first Chinese to arrive in the Northern Territory in 1871. He had a market garden at Yam Creek, then worked as a jeweller. During April 1874 he was arrested for theft and imprisoned without trial for a year. He escaped from the Palmerston Gaol in April 1875. His whereabouts was tipped off to Police Inspector Foelsche, who sent two troopers to apprehend him. They ambushed him on the evening of 11 May 1875 and he was killed by a policeman’s shot when he slipped from his hiding place above his boat and fell. He was not armed and not considered a dangerous criminal, and his treament and death caused public controversy.

An account of the inquest into Ah Kim’s death appeared in Northern Territory Times and Gazette on Saturday 15 May 1875 and in it is a mysterious contradiction. One of the two troopers (who incidentally were brothers) stated that after several warnings that he would be shot if he did not surrender, Ah Kim had jumped to the ground from his improvised hammock. Frederick George Guy, the surgeon who examined the body, reported a jagged wound about one and a half inches long and one inch deep on the left cheek under the eye and the left cheek bone completely smashed, and also the lower jaw, also that either the third or fourth cervical vertebra was fractured and the carotid artery severed. When questioned by a Juror he stated that the direction of the bullet was downwards and backwards.

Scratched by Sub-Inspector Foelsche on the bottom of the glass plate (above) are the words “Capture of Ah Kim at 10.20 p.m. on May 11, 1875.”

Why then did Foelsche painstakingly reconstruct this event when amongst his photographs are no other crime scenes? He must have considered the incident dramatic enough to be re-enacted for the police archives, or for his own personal records.

Necessarily, given the wet-plate technology, the photograph was taken in broad daylight, though the actual shooting took place in darkness at 10.20 p.m. Even so, there is considerable subject movement; though where he can direct his subjects, Folesche is careful to instruct his subjects to ‘freeze’ in apparent motion, like the apparently walking man (below) whose ‘vibrating’ broom handle gives away the fact that he is standing stock still for the considerable length of the exposure required.

This restriction necessitates some retouching to the Ah Kim image to add the smoke from the trooper’s gun by lightly painting over the negative. This figure also shows blur because of the subject swaying in the course of the long pose.

Though the State Library of South Australia describes the stand-in for Ah Kim, the victim, as ‘a stuffed dummy’, close inspection shows that figure too betrays motion blur, supports itself on the left arm and appears to have human musculature; it is not likely to be a dummy.

Making a photograph with wet-plate technology of a dynamic action like this shooting is a challenge, and perhaps that is why it does not agree with the trooper brothers’ account nor with the evidence of the surgeon. Is this a pre-cinematic construction of a narrative in which all the actions take place simultaneously to fit into one image? Or had Foesche intended this reconstruction to incriminate his men, given that Ah Kim is shown here being shot in the back? Or was this an attempt to clear their names in the face of the criticism of the shooting in the press, which decried it as legalised murder, by showing, as best he could given the constraint of long exposure, that the victim was about to escape, leaping from the tree?

Ah Kim had hidden his boat behind another and disguised his sleeping place above it as a fishing net (his makeshift hammock) slung casually over a tree-trunk. The surgeon testified in response to questioning, that the escapee was shot in the face and that the bullet entered his cheek and traveled ‘downwards and backwards’ toward his neck. That is consistent with his being shot on the ground, in which case the trooper, from the position pictured, would have had to shoot through the hull of at least one boat (remember no traces of bullet marks were found other than in the body), or to have moved around the vessels to reach Ah Kim’s after he leapt or fell from the tree. Was he shot in cold blood as he lay in surrender on the ground? Was he killed as he slept in his hammock?

Even the justification for shooting Ah Kim is contradictory, as he was not about to shoot back…it was not asserted in court that his shooting was in self-defence. Some said he was at other times armed with a revolver and was aggressive to some who approached him, but the troopers testified that they could find no weapon on him. Others who removed the body claimed to have found the pistol underneath it. Significantly, Foelsche does not show Ah Kim holding a gun.

Rather than being a ‘reconstruction’ this photograph appears to be a fabrication. Note that the title Foelsche scratched into its emulsion is “Capture of Ah Kim at 10.20 p.m. on May 11, 1875″, not the “Shooting of Ah Kim”. It answers no questions, furthermore it leaves no insight into what Foelsche intended in taking it, only a lingering suspicion that it covers up important facts, that there is something sinister in his capture of images of so many gaoled and chained aboriginal prisoners.