December 27: For some, it’s back to work. Labour is the subject of two photographers working in quite separate styles, separated by 2,000 kilometres, and across pre-industrial and late-industrial societies.

December 27: For some, it’s back to work. Labour is the subject of two photographers working in quite separate styles, separated by 2,000 kilometres, and across pre-industrial and late-industrial societies.

Estonian Johannes Pääsuke lived a full but brief life of 25 years and died in a train accident on this date 27 December 1917 (in the Julian calendar in use until Russia changed on 14 February 1918, to the Gregorian, in which the date is 8 January 1918). Like the Swiss Jakob Tuggener, Pääsuke was a filmmaker as well as a photographer.

Tuggener, 12 years the younger (1904–1988), features in a current 3-month-long exhibition Machine Age / Maschinenzeit at the Fotostiftung Schweiz, Grüzenstr. 45, 8400 Winterthur, held appropriately in an industrial city in northern Switzerland, until 28 Jan 2018.

Characteristic photographs below by each of these photographers demonstrate the differences in their approach and subject matter. Pääsuke’s barefoot cyclist and his remarkable wooden bike are framed centrally against the flat grassy landscape of mid-southern Estonia. It is an ethnographic image in which the boy’s appearance and his artefact are posed with the intention to convey information about him and his social status, and his aspirations.

The ethnophotographic image is conventionally made by an outsider, but despite his comfortable middle-class background, Pääsuke is less objective because he is clearly sympathetic to this young compatriot and to others that he photographed in rural Estonia for the Estonian National Museum’s Department of Homeland Pictures. They employed him from 1912 after his photographs, made of his own volition over the four years previous, came to their attention. He made more than 1,300 photographs on glass plates in his national ethnographic project, and the cyclist was from one of two larger series made across much of the south of the nation during 1908–13. At the same time as the photographs, he made films with a motion picture camera he had cobbled together with second-hand parts and thus became Estonia’s first filmmaker from 1912.

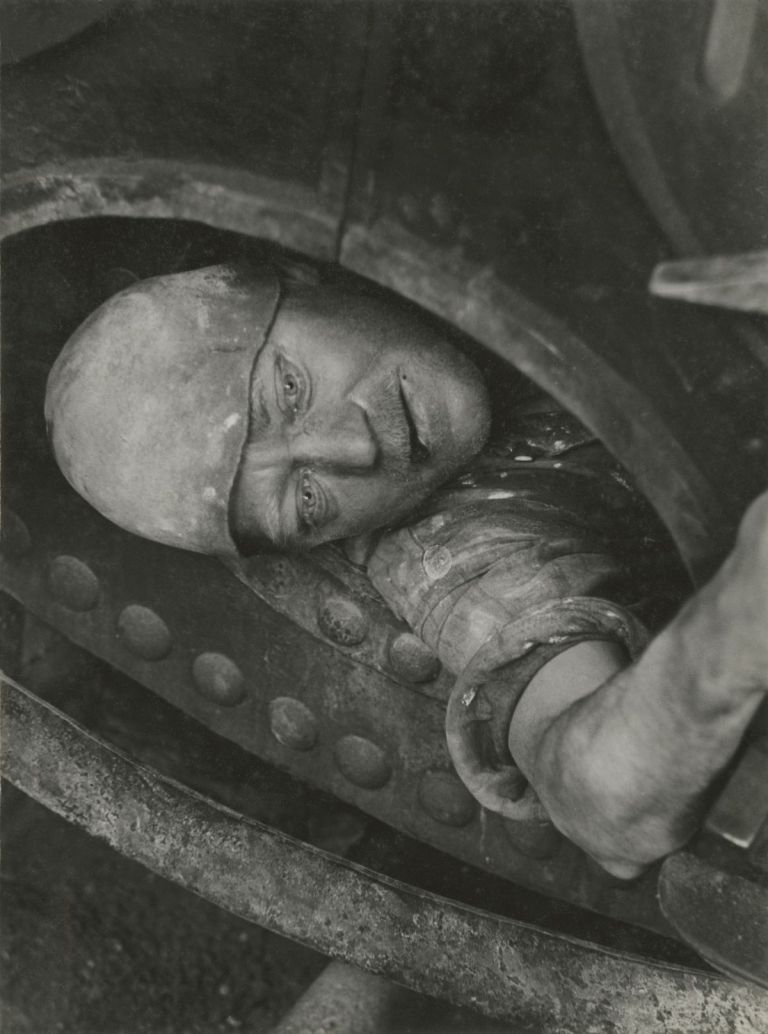

Where the Estonian peasant boy might be said to engage in a ‘cargo cult’ relation with the industrial, Tuggener presents us with the worker inside the boiler, appearing to be consumed by the machine.Significantly his photograph is from Fabrik: Ein Bildepos der Technik that he published in 1943 in the midst of WW2 and is representative of the book in representing the fusion of human and machine.

Some commentators interpret in that a positive attitude to industrial progress while others, more feasibly given its context of world conflict, decode it as being a symptom and symbol of the irrationalist and nationalist embrace of technological progress as a catalyst of emerging right-wing ideologies in Germany and ltaly, and even in turn-of-the-century Switzerland. This latter perspective is that of photo-historians Martin Gasser (*1955) and Guido Magnaguagno (*1946) who have both researched and written on Tuggener, who is becoming more widely known.

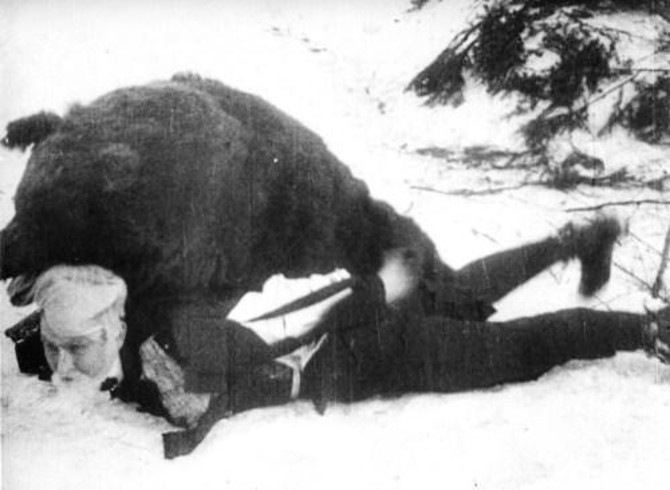

Pääsuke, on the other hand, is less well-known though he is well recognised and celebrated in his native Estonia, where he took up photography at age fifteen. An Estonian-language book Johannes Pääsuke: Mees kahe kaameraga (‘Johannes Pääsuke: Man with Two Cameras’) was published in 2003 by the Museum and a feature film on his short life, Johannes Pääsukese tegelik elu, directed by Hardi Volmer (*1957) is due to be released in 2019, but his photographs deserve better attention internationally. They, like Tuggener’s disclose a political perspective. That is evident in Pääsuke’s 1914 film Karujaht Pärnumaal (Bear Hunt in the Pärnu County), which is a satire on urban bureaucracy and rivalries between Estonian and Russian ethnic groups.

Another comparison confirms the photoethnography of Pääsuke and the Modernism of Tuggener, through the role of an anvil in each photograph. Pääsuke treats the object as an iconic but incidental sign of the subject’s profession, secondary to our sense of conversing with the blacksmith in his shop. Tuggener by contrast is captivated by the play of light and reflection on an object that bears the traces of labour and thus stands in for the human subject.

Where workers are portrayed by Tuggener the result is dynamic; the human is in action, seen in the course of hard work.

Where Pääsuke’s subjects are at work, we see them acting communally, as part of a team, just as he himself does in his partnership with his assistant, H. Volter who accompanied him to the Estonian coast, from 10 June to 29 July 1913, mostly on foot, with both toting packs and also cameras, tripods and plates.

Three hundred and seventeen photographs survive from this trip, mostly of the island communities of Saaremaa and Muhu.

In 1915, Pääsuke was conscripted, mobilized on 8 September and was in St Petersburg on 14 November. Recognized there as a photographer, he documented activities for the army both in Russia proper and in Estonia. Pääsuke died in a train accident in 1917/18 in Orsha, Belarus. It is sobering to imagine what else he may have achieved if his life were longer!

In 1915, Pääsuke was conscripted, mobilized on 8 September and was in St Petersburg on 14 November. Recognized there as a photographer, he documented activities for the army both in Russia proper and in Estonia. Pääsuke died in a train accident in 1917/18 in Orsha, Belarus. It is sobering to imagine what else he may have achieved if his life were longer!

In 1949, the new editor of Camera magazine, Walter Laubli (1902–1991), published substantial portfolios of Jakob Tuggener and Robert Frank (1924–2009) as representatives of the ‘new photography’ of Swiss life.

After experiencing the glories of night-life at the then famous balls held by the Reimann School at which he trained in photography, from the 30s to the 50s the soirées in hotels like the Palace in St. Moritz, the Baur au Lac and the Dolder Grand Hotel & Curhaus obsessed and enchanted Tuggener, with their “alabaster light” illuminating a “fairy tale of women and flowing silk”.

His camera was his entree to this privileged universe otherwise denied to a man of his middle-class origins. These are a remarkable foil to his industrial images and it is hard to believe, though some commentators deny it, that this man who lived like a hermit for the sake of his photography would not intend at least some irony if not outright critique of the wealthy.

The October issue of Camera included a thick portfolio of Tuggener’s photographs taken at these high-class entertainments and in factories, a world more familiar to him from his early apprenticeship as a technical draftsman in Zurich, as well as a series of stills from his silent films, with an introduction by Hans Kasser (1907–1978), himself a photographer and member of the Werkbund.

The last issue of 1949 was devoted to Robert Frank, returned to his native Switzerland after two years abroad, with pages including some of his first pictures from New York. Tuggener was a role model for the younger artist, first mentioned to him by his boss and mentor, Zurich commercial photographer Michael Wolgensinger (1913–1990), who knew Frank would never fit the system. Tuggener, as a serious artist who had left the commercial world behind, was the “one Frank really did love, from among all Swiss photographers,” according to Guido Magnaguagno.

Fabrik, as a photo book, was a model for Frank’s Les Américains : The Americans published ten years later in Paris by Delpire, 1958, and it takes you on free-ranging tour through the industrial gargantua, guided by Berti, the factory errand-girl, a machine-age Iris (messenger of the gods);

While some of its images are drawn from Tuggener’s commercial work promoting contented, peaceful workers and the introduction of new, ‘clean’, technology of electronics and hydroelectric power, the meaning of Fabrik is left to the viewer to discover between its pictures, its glimpses of an overwhelming industrial whole; it is essentially filmic on a cryptic film-noir level, a revelation to Frank.

Martin Parr and Gerry Badger in their The Photobook: A History note;

…as Arnold Burgauer cogently states in his introduction [to ‘Fabrik: Ein Bildepos der Technik’], Tuggener is a Jack-of-all-trades: he exhibits the sharp eye of the hunter, the dreamy eye of the painter; he can be a realist, a formalist, romantic, theatrical, surreal. Tuggener moves effortlessly between large-format lucidity and grainy, blurred impressionism, in a book that is a decade ahead of its time.

Although Fabrik was not commercially successful, Tuggener considered the book a great artistic coup, and continued photographing labour and industry to produce two more book maquettes: Schwarzes Eisen (Black Iron, 1950) and Die Maschinenzeit (The Machine Age, 1952). Journalist Arnold Burgauer described that latter as a “brilliant and sparkling factual report on the world of the machine, its development, its potential and its limits”.

Love this posting James… never knew much about Tuggener before!

LikeLike

Thank you Marcus. Yes an extraordinary effort by a man who apparently lived like a hermit to give his all to photographing the two worlds, of privilege and labour, separate but interdependent.

LikeLiked by 1 person

James, a new posting on the Tuggener exhibition at Fotostiftung Schweiz on Art Blart at https://wp.me/pn2J2-9Qd hope you enjoy Marcus

LikeLike

Brilliant, Marcus! Thank you for more in-depth information on the man and more, and more beautifully reproduced, images to add to those I had managed to track down. Your consideration of Tuggener’s influence on fellow Swiss, Robert Frank, and the differences between them too, is excellent.

LikeLike