The historian of photography who is also a photographer is a special case.

The historian of photography who is also a photographer is a special case.

It is rather extraordinary that three such people should have been born on this date. Gisèle Freund in 1908, Jean-Claude Gautrand in 1932, and Allan Douglass Coleman, known as A.D. Coleman in 1943.

Freund was born into a wealthy Jewish textile merchant family in the Schoneberg district of Berlin and her father, Julius Freund (1869–1941) was a collector of German paintings, drawings and prints from the 19th and 20th century whose professional interest in pattern and form no doubt inspired his acquisition of photographs by Karl Blossfeldt. Freund related in 1977 that she “was born under the now world-famous Chalkstone Rocks of Rügen by Caspar David Friedrich.” Her exposure to fine art informed her future writing.

Freund’s father bought Gisèle her first camera for her fifteenth birthday; a Voigtländer 6×9. In 1929, as a reward for completing her studies he also gave her a Leica because of her developing passion for photojournalism.

She studied sociology at the universities of Freiburg in Breisgau and then in Frankfurt, where her professors were Karl Mannheim (1893–1947), best known for his Ideology and Utopia (1929), and Norbert Elias (1897–1990), author of a major work of historical sociology, The Civilizing Process and The Civilization of manners and Dynamics of the West (1939). Elias inspired her to write her thesis on Photography in France in the nineteenth century which was to become the first on the sociology of the image. Between 1931 and 1933 she attended the Institute for Social Research led by the famous Professor Theodor W. Adorno (1903–1969) and where she befriended the philosopher Walter Benjamin (1892–1940), with whom she joined the socialist student group Rote Studentengruppe, which her photographic work reflects in documentation of the last May Day demonstration in Frankfurt am Main by students and unemployed in Germany before Hitler came to power. She recalled the event in 1985;

In 1932 I was a sociology student, but my hobby was photography. My father, in 1928, had given me a Leica camera, a make that had been on the market for only six years. I was impressed by the ease with which this little camera could be handled and the possibility of taking almost forty pictures without changing the reel (film in those days was not yet numbered). Sunday, May 1, Frankfurt am Main. The weather is splendid, not a cloud in the transparent sky, and the spring air is surprisingly mild.

In the dawn, lines of trucks transporting men and women approach the city. All of the passengers get off as soon as they arrive and line up in columns, led by people carrying placards covered with political slogans. The streets swarm with a crowd that moves toward the Roemerplatz, the large medieval square in the old city, alongside the cathedral. Soon the square is filled by a veritable human sea and the arriving columns must station themselves in the adjoining streets.

May Day is the holiday celebrating labour, but most of the faces are grim and anxious. At least a third of those assembled on this day are unemployed. In 1932 Germany had more than six million unemployed, and this, when one includes their families, represents a total of twenty million people living in poverty. It is the greatest economic and social disaster ever experienced by the Weimar Republic, which had been established only thirteen years before. The crisis had begun with the crash of the New York stock exchange in 1929. Considerable American capital was invested in Germany. Banks collapsed, thousands of businesses were ruined, and the climate became one of catastrophe.

She fled Hitler’s Germany after Benjamin, and once she had completed her studies in Paris in 1936 she photographed him, her occasional chess partner. She admired him and Benjamin wrote a positive review of her dissertation.

“I met Walter Benjamin and photographed him as I saw him,” she says of her picture of him reading in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France. It is typical of her work in showing the subject in their habitual surrounds in available light, and it appears almost arbitrary and candid. It is the first of numerous portraits of Benjamin that she made, including the now-famous colour photograph in which a fatigued Benjamin, then a little known scholar (and still misunderstood), barely manages to look into the camera with his hand to his forehead. It is an image in which one can read a deep melancholy; one of Freund’s most affecting, second only to her portrait of Virginia Woolf (1939) taken a few weeks before the novelist’s suicide.

Freund’s lover Adrienne Monnier (1892–1955), was the proprietor of La Maison des Amis des Livres bookshop. Monnier offered advice and encouragement to Sylvia Beach (1897–1962) when Beach opened an English-language bookstore called Shakespeare and Company in 1919 at 12 rue de l’Odéon across from Monier’s shop in the Latin Quarter.

Both bookstores became gathering places for French, British, and American writers, and the two became lovers for over fifteen years, until in 1936 Beach and Monnier had grown friendly with Freund.

Freund was stateless until Monnier arranged her a marriage of convenience to obtain a visa. A year later, while Beach was visiting America, Freund moved into the apartment Adrienne and Sylvia shared. On return Beach withdrew to the apartment above her shop, but friendship endured, and often Beach took her evening meal with Monnier and Freund.

Monnier published Freund’s doctoral dissertation as La photographie en France au dix-neuvieme siècle under the La Maison des Amis des Livres imprint in 1934. She also introduced Freund to important writers and artists of the era of whom she made portraits. They include giant figures; Virginia Woolf, James Joyce, Colette, André Malraux, Henri Michaux, Michel Leiris, Marguerite Yourcenar, Jean Cocteau, Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Samuel Beckett, and at the International Congress of Writers for the Defence of Culture in 1935, she photographed André Gide, Aldous Huxley and Boris Pasternak. Monnier and Freund remained lifelong companions.

It is interesting to compare her 1934 published thesis, which was condensed and revised to include new material as Part One of Photography and Society and published for the first time in English in 1974, with the history that Benjamin promulgates in his Petite histoire de la photographie published for the first time in Literarische Welt, Berlin, 1931, and to consider her Part Two against ideas in his 1936 Das Kunstwerk im Zeitalter seiner technischen Reproduzierbarkeit that considers the social effect, and changed aesthetic affect, of the new medium particularly on the value placed on the original artwork.

A dialogue between Freund and Benjamin clearly took place over their chessboard around the history of the medium and this point about photographic reproduction, as she writes two years before his The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction in her chapter ‘Photography as a Means of Art Reproduction’ in Photography and Society, Part One;

The debate over the artistic value of photography, dating from the invention of the camera, seems only a limited problem in comparison to the importance of photography as a means of art reproduction. Until photography entered the scene, artworks had been accessible only to an elite few. But when they could be reproduced by the millions, art became available to everyone. This change began with engraving and lithography, but only with the invention of photography did works of art lose the mystique of the unique creation.

Photography has not only altered the artist’s vision, it has changed man’s view of art. The quality of a photograph of a sculpture or a painting depends on the man behind the camera: his ability to frame, to light, and to emphasize the details of his subject can completely change its appearance. Reproductions in art books change according to the scale of the reproduction. An unusually enlarged detail distorts the overall effect of the sculpture or a painting; a miniature can seem as large as Michelangelo’s David in Florence. In his Musee imaginaire, Malraux asserts that ‘ reproduction has created fictitious works of art by systematically falsifying scale and by presenting stamps of oriental seals and coins as if they were columns, or amulets as if they were statues.’

If photography can misrepresent a work of art by distorting its dimensions, it was immensely helpful in removing art from its isolation.

In Part Two Freund extends this phenomenon of mass communication of images to the press, while Benjamin, in his eclectic manner, links to the ‘aura’ of cinema. In doing so, Freund uses examples from her own long experience of making and selling photographs which she continued to do until the 1980s, her last major assignment being the widely published and politically effective 1981 official portrait of President Francois Mitterrand.

She speaks from her experiences in picturing power;

Photography’s tremendous power of persuasion in addressing the emotions is consciously exploited by those who use it as a means of manipulation. […] the so-called liberal capitalist countries but also the dictatorships, both left- and right-wing, have exploited photography’s persuasive power. The photograph of the chief of state carried over the crowds in parades and demonstrations, or decorating state offices, is for some the symbol of the father and for others the Orwellian ‘Big Brother.’ It inspires love or hate, confidence or fear. Its intrinsic value is based on its power to arouse one’s emotion.

During World War II had she sought refuge in Argentina and contributed to the anti-Nazi efforts of France Libre, and there her host Victoria Ocampo introduced her to Borges, Maria Rosa Oliver, Bioy Casares and members of SUR. In 1943 her reports from Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego featured powerful landscapes. Back in France in 1946 she worked from 1948 for Magnum as a photojournalist.

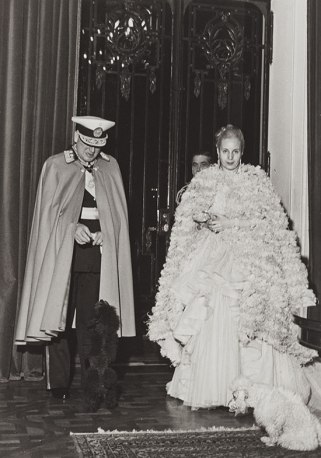

She was not afraid to be controversial; in 1950, LIFE printed her photographs of the bejewelled Evita which put her out of favour with Perón regime and forced Freund’s retreat to Uruguay, and in 1954 her socialism had her US visa cancelled during the anti-communist McCarthy witch-hunt and she was forced to leave Magnum.

So she writes with authority in Press Photography of Part Two;

The introduction of newspaper photography was a phenomenon of immense importance, one that changed the outlook of the masses. Before the first press pictures, the ordinary man could visualise only those events that took place near him, on his street or in his village. Photography opened a window, as it were. The faces of public personalities became familiar and things that happened all over the globe were his to share. As the reader’s outlook expanded, the world began to shrink.

Freund was proud of her use of colour and the 35mm camera as influential practical achievements. The days of the specialised colour camera were numbered when, driven by the demands of the motion picture industry, Agfa and Kodak brought out new multilayer colour positive film in 1938, and Agfa their chromogenic negative film in 1939 with 278 newly patented features. These films could be used in any camera, including Freund’s Leica and Rollei. Agfa issued a companion colour paper for printing from their negatives. Freund embraced the technology, her early adoption a means to distinguish her work from others at a time when she relied on the medium for a living due to her prewar separation from her family.

In her own estimation, recorded in 1977, her very straightforward portraits do not stand out as works of art but as valuable records of important people. She had read the sitters’ works and often would spend hours, even days, discussing them before photographing the writer. Freund regarded them as a means by which readers of these writers could relate to the person;

I certainly didn’t pretend to be making works of art or inventing new forms, I wanted to show what means the most to me: people, with their joys and sorrows, hopes and fears

The unretouched directness of Gisèle Freund’s imagery reflects in her writing in Photography and Society, especially the second half which, just as candidly and bluntly, dissects the structures and machinations of the news industry. If Freund’s words and ideas now seem obvious, it is a sign of her effectiveness and influence in publishing them.

A blog post, if one expects it to be read, should not exceed 2000 words, so rather than go over that limit, I shall leave discussion of Jean-Claude Gautrand and A.D. Coleman, whose writings and photography I’d like to compare, to December 19, 2018. Do join me then!

One thought on “December 19: Praxis/Thesis”