May 22: Back to beginnings; the photography of childhood.

May 22: Back to beginnings; the photography of childhood.

Today marks the death in 2013 of one of the biggest early inspirations for my passion for photography, American Wayne F. Miller (*1918, Chicago).

On our bookshelf in suburban 1950s Melbourne my father kept three books that suffered spinal damage from my attentions; The Family of Man, Ed van der Elsken‘s Love on the Left Bank, Wayne Miller’s The World is Young. The latter is the only one to survive relatively intact. In fact all three books are related, as we shall see; that is how small the photography world was in the late 1950s, and how dominant was the American influence.

Miller currently features in the exhibition Magnum Analog Recovery at LE BAL 6, Impasse de la Défense, 75018 Paris, that commenced on 29 Apr and finishes on 27 Aug 2017. This year marks 70 years since Magnum photo agency and the exhibition presents a range of the cooperative’s holdings with contemporary prints and designs for books and publications. These date from the creation of Magnum Photos (1947) till 1977. It includes Miller amongst Magnum photographers Eve Arnold, Micha Bar-Am, Bruno Barbey, Ian Berry, Werner Bischof, René Burri, Robert Capa, Cornell Capa, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Raymond Depardon, Elliott Erwitt, Leonard Freed, Paolo Fusco, Jean Gaumy, Burt Glinn, Philip Jones Griffiths, Ernst Haas, Hiroshi Hamaya, Erich Hartmann, David Hurn, Richard Kalvar, Josef Koudelka, Hiroji Kubota, Sergio Larrain, Guy Le Querrec, Erich Lessing, Herbert List, Danny Lyon, Constantine Manos, Susan Meiselas, Inge Morath, Gilles Peress, Marc Riboud, George Rodger, David (Chim) Seymour, Marilyn Silverstone, Chris Steele-Perkins, Dennis Stock, Kryn Taconis, Nicolas Tikhomiroff, and Alex Webb.

Wayne F. Miller studied basic photography at the Art Center School of Los Angeles from 1941 to 1942, before joining the United States Navy, where he was assigned to the Naval Aviation Photographic Unit directed by Edward Steichen (1879–1973), world famous by then as a remarkable photographer. With an enviable background in the earliest fashion photography for Condé Nast’s Vogue and Vanity Fair, advertising and fine art in the Pictorialist and Secessionist styles he was to be a valuable mentor and contact for Miller who said in an interview with Smithsonian magazine’s Alice Keys:

Steichen was a father figure to me. He was a fascinating teacher, never criticizing, always encouraging.

Born in Luxembourg, Steichen had migrated to the USA in 1880 as a young child. In 1905 in partnership with Alfred Stieglitz, in whose Camera Work he frequently appeared, they opened the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession, known as 291. Steichen’s instruction to Miller was:

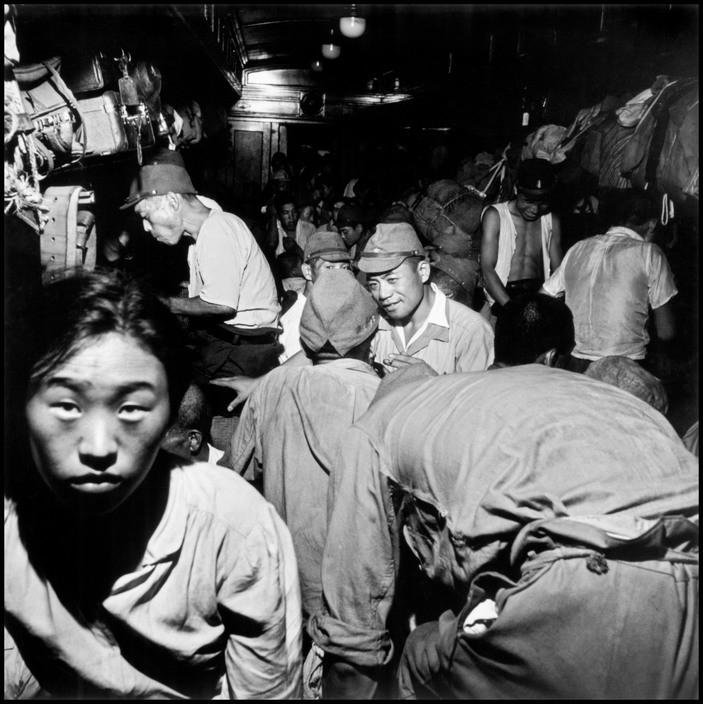

I don’t care what you do, Wayne, but bring back something that will please the brass a little bit, an aircraft carrier or somebody with all the braid; spend the rest of your time photographing the man.

In other words his request was that he concentrate on the ‘little man’ and his struggle within the bigger picture. It was advice by which Miller stood; he was a humanist photographer.

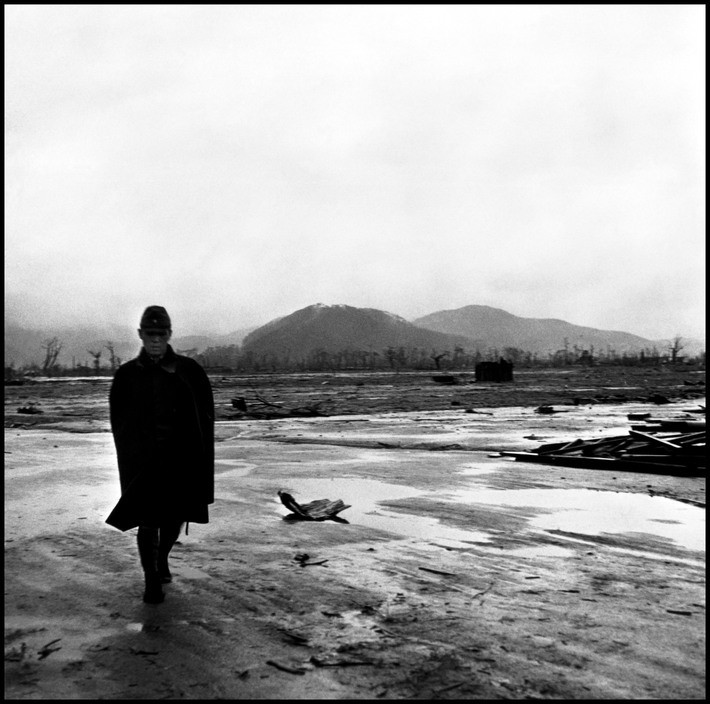

On August 6, 1945, the U.S. bomber Enola Gay had dropped a 20 megaton atomic bomb on Hiroshima’s population of about 300,000. One month later, Miller photographed the devastated city, but in the brief day he had there he spent most of the time getting up close to the victims for a series of medium format photographs.

Miller does not say what it must it have been like for these fly-covered sufferers of horrible burns to have these photographs taken, with flash, in their squalid temporary hospital, when the photographer was their victorious enemy.

After the war, while Steichen became Director of Photography at New York’s Museum of Modern Art until 1962 and Miller settled in Chicago working as a freelancer. Steichen journeyed to Europe in 1951 to collect photographs for MoMA exhibitions, Five French Photographers: Brassai; Cartier-Bresson, Doisneau, Ronis, Izis (December 1951-24 February 1952), and Post-war European Photography (27 May-2 August 1953).

It was during that visit that he met with Ed van der Elsken who with typical enthusiasm brought him piles of prints of images he had been making on the Left Bank in Paris amongst the bohemians.

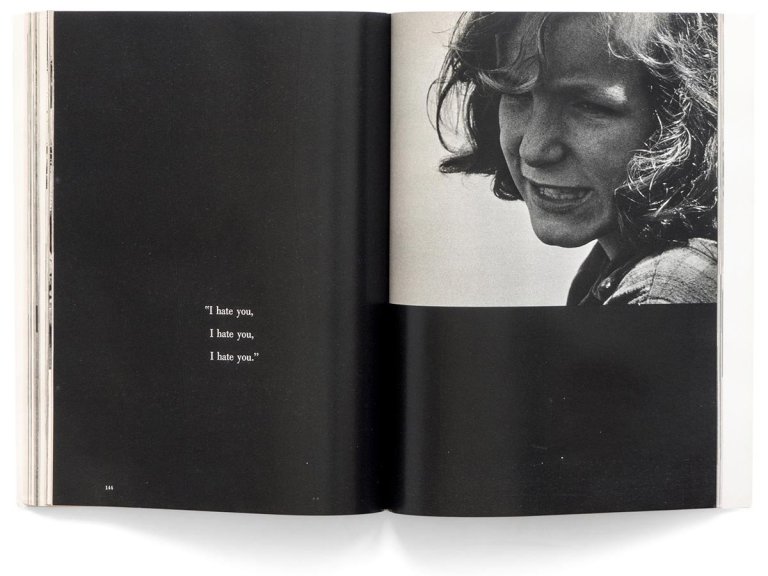

Steichen advised Van der Elsken to edit the photographs into a book. Thus was Love on the Left Bank (one of my three favourites identified at the top of this post) born in 1956. It became a classic photo-roman, the story of a young Mexican man, a stand-in for Elsken himself, and his unrequited love for Ann (in real life the Australian dancer and artist Vali Myers).

Steichen advised Van der Elsken to edit the photographs into a book. Thus was Love on the Left Bank (one of my three favourites identified at the top of this post) born in 1956. It became a classic photo-roman, the story of a young Mexican man, a stand-in for Elsken himself, and his unrequited love for Ann (in real life the Australian dancer and artist Vali Myers).

In the meantime, Miller obtained two consecutive Guggenheim Fellowships 1946-48 that enabled him to photograph The Way of Life of the Northern Negro, which was later published as Chicago’s South Side.

His idea was to unite black and white in America by showing the postwar demographic change to Chicago as thousands of blacks from the South migrated there, some of them becoming prosperous and middle class. Miller’s treatment of this story was so sympathetic and positive that Ebony Magazine (est. 1945, Chicago) set it beside Richard Wright’s bleaker essay The Shame of Chicago and also, in a first for the magazine, gave him a byline.

In 1949 Miller moved permanently to Orinda, California, and worked for LIFE until 1953. For the next two years he and his wife Joan were Edward Steichen’s assistants on the Museum of Modern Art’s historic show created by Steichen, The Family of Man, a vast exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art consisting of over 500 photos that depicted life, love and death in 68 countries. It toured the world and still reputedly holds the record for attendances of a photography exhibition. The book of the exhibition (1955), which is still in print, was the second on our bookshelf.

Steichen selected eight of Miller’s photographs for The Family of Man, one being Miller’s photo of his son, David, being delivered by his grandfather (it was later enclosed in the Voyager spacecraft launched in the late 1970s; I wonder what the aliens will make of it?).

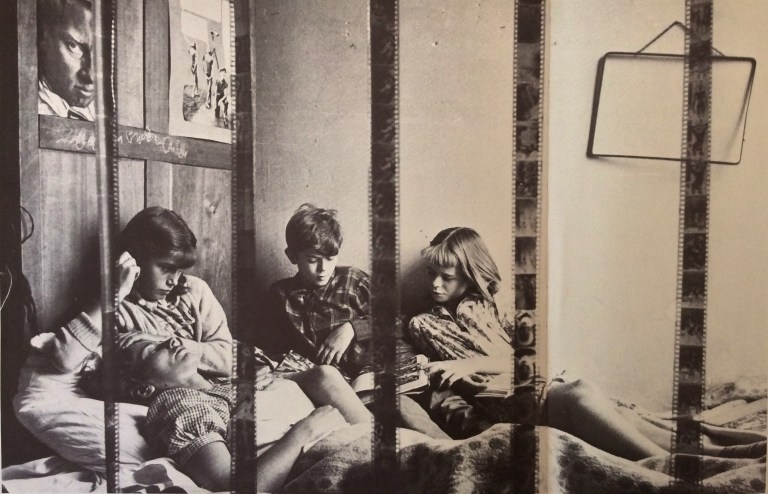

A combination of factors contributed to the last of these favourite books, The World Is Young (1958). Miller’s growing family, the influence of having edited The Family of Man from 2 million American and international images, and the humanist ethos of Steichen and his exhibition, as well as their shared desire to do something affirming of peace after the World War.

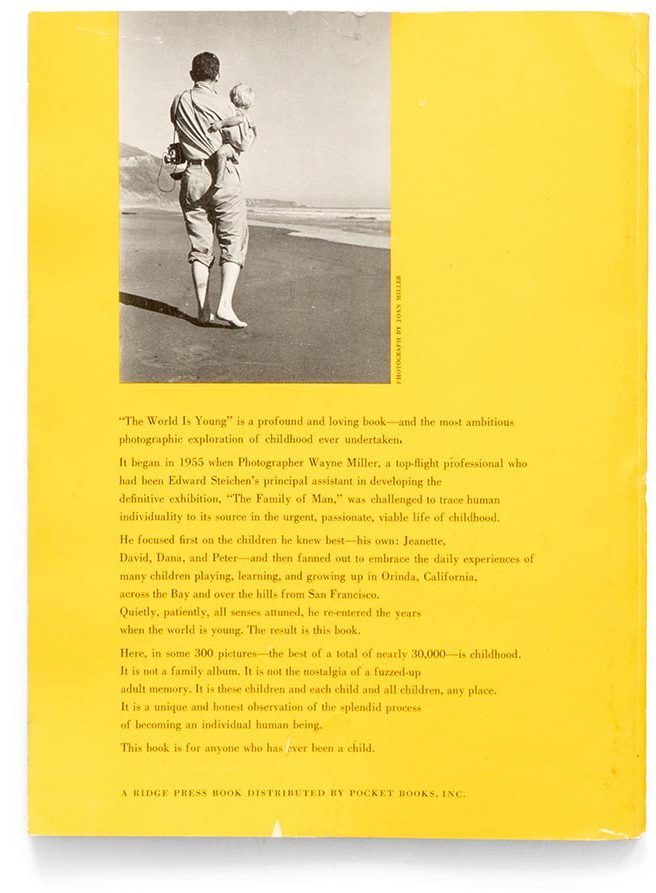

The back cover blurb elucidates the sentiments breathlessly with the rather bold claim that: “The World Is Young is a profound and loving book – and the most ambitious photographic exploration of childhood ever undertaken.”

It does however, if you ignore the hyperbole, summarise the process; that Miller had commenced on the project inspired by and straight after completing his work with Steichen on The Family of Man, in 1955; that he started by photographing his own children Jeanette, David, Dana, and Peter, and then branched out to start simultaneously photographing other children in the community “playing, learning and growing up in Orinda, California, across the Bay and over the hills from San Francisco;” and that he selected a proportion of 1 in every hundred of 30,000 images he took, for the book. The blurb also claims:

It is not a family album. It is not the nostalgia of a fuzzed-up adult memory. It is these children and each child and all children, any place.

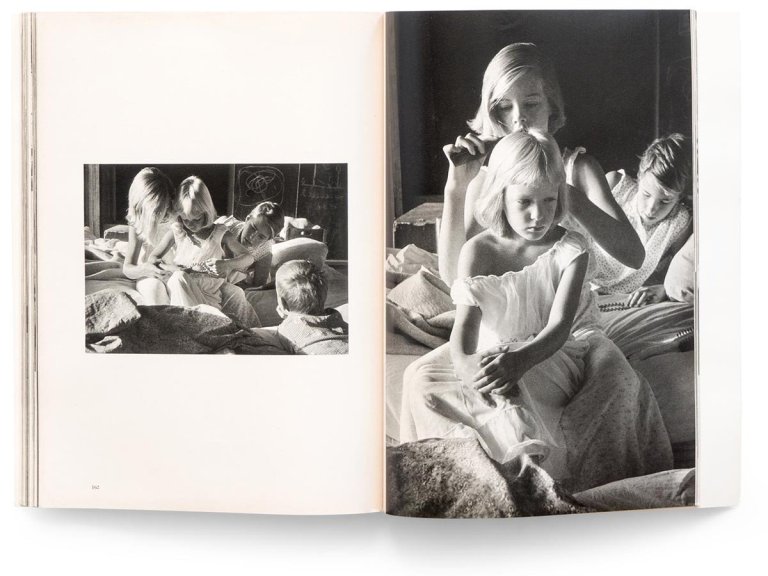

In fact nothing could be further from the truth. What we see is a very privileged childhood quite different from that of those in black families in Chicago.

Orinda was a relatively new area of housing established in 1937 with the building of the Caldecott Tunnel east-west through the Berkeley Hills to Oakland. Miller described Orinda as “a new community without tradition.” A 1941 Streamline Moderne movie theater marked an outpost of modernity amidst new schools, new shopping centres, and new freeways. The population at the time of the book was just over 5,000 and Miller’s pictures show unmade roads and wooded blocks.

The family (three children, a fourth soon to come) was to move into a new house in the Californian modern style designed by Mario Corbett from their brick subdivision house in Chicago and, typically, into the suburbs in the rolling hills covered with oak trees east of Berkeley. Corbett’s design is a rustic version of Modern, distinctively Californian of this era, lined with unpainted redwood and with large areas and plenty of glass inviting interaction with the outside and ample play areas for the children.

This house is the backdrop for most of the pictures, and though some were shot in their pied-à-terre in New York while Wayne and Joan worked with Steichen, that is easily identifiable as a different place.

This house is the backdrop for most of the pictures, and though some were shot in their pied-à-terre in New York while Wayne and Joan worked with Steichen, that is easily identifiable as a different place.

As a child growing up in a similar family, also enjoying a new suburb being developed out of bayside ti-tree and sand dunes, I could easily empathise with the subjects of this book, despite its idiosyncratic Americanness, crew-cuts and ‘slumber parties’.

For my family however, for various reasons, the idyll was brief; so from my perspective the book is better seen as an intimate view of an era of prosperity, and now vanished near-pristine environments which an ordinary middle-class professional family could easily access, that is never to be repeated.

For my family however, for various reasons, the idyll was brief; so from my perspective the book is better seen as an intimate view of an era of prosperity, and now vanished near-pristine environments which an ordinary middle-class professional family could easily access, that is never to be repeated.

These children are now in their 60s and 70s and the world is now much more complex than an essay like Miller’s could convey. Sally Mann (born 1 May 1951, and also the child of a doctor), was a beneficiary of that period of affluence, educated at the The Putney School, an independent alternative high school in Putney, Vermont. Her own longer-term project is part of a continuum that stretches from Miller’s, and it bears a comparison that has yet to be thoroughly investigated. Again it is the work of a financially well-to-do artist and consequently presents a rare existence which may be the norm for collectors of photography, but not for the majority of the world population.

Contemporaneous with Miller’s The World Is Young, Ed van der Elsken also closely documented his adopted family, the children of Ata Kando, Tamás, Madeleine and Juliette, with whom he lived in Paris and Amsterdam. Their conditions, like those of millions in war-ravaged Europe, were much different.

This is why OnThisDateInPhotography questions the realism of the perspective of an American-centred photographic history represented by The Family of Man or The World Is Young, and looks elsewhere for an alternative, broader history, and the well-springs of the next applications of, and innovations in, the medium.

Miller’s pictures do however represent a worthy model of inconspicuous, patient, ‘fly-on-the-wall’, ‘warts-and-all’ photojournalism of everyday bourgeois life, innovative in lovingly portraying, not the agonies of war or poverty, but the family dramas and joys of existence of a particular window in time.

For me, as a young photographer, to achieve commitment, passion, technique and approach the like of Miller’s was my aspiration.

A fine celebration of Wayne Miller and his work which also influenced my approach to photography. My daughter was named after his Dana, and we met Wayne and his family in California in 1980, by which time he had moved into forestry.

Thank you,

John B Turner, Beijing

LikeLike

Thank you John, lovely to meet another admirer of Wayne Miller, and especially one who has had the privilege of meeting the man!

With Regards,

James

LikeLike