March 29: To picture is to conceive.

March 29: To picture is to conceive.

Today is the birthday of John Hilliard, UK conceptual photographer and filmmaker born in 1945.

His first use photography was as a student during the 1960s. As the conceptual movement gained pace, the camera was a dominant means of documenting performances and temporary and/or site-specific installations. During his studies at the St Martin’s School of Art in London he was awarded a travel scholarship to the USA in 1965, and, influenced by the landscapes of the Mid-West and the architecture of New York and Chicago, began making site-specific installations. These he documented photographically, with the photographs gradually displacing the installations as a means of presentation and forming the basis of a first solo exhibition at Camden Arts Centre, London in 1969.

Joseph Kosuth’s One and Three Chairs of 1965, however, begins to engage with the conceptual dimension of the photograph by pointing to the limits of its representation of reality. Next to the actual chair, he asks, is its account of the object any more reliable or informative than a dictionary definition.

Hilliard extended on this realisation that the camera was not simply a neutral device for recording fact. His exposure to semiotics guided his insight that the metonymic utility of the photographic image; our expectation that a photograph could stand in for the actual subject, deserved more thorough investigation. Drawing on the language and history of the medium and using the rigorous visual and intellectual inquiry that typified Conceptual Art and Minimalism in the late 1960s, he challenged the myth of photographic truth and set out to find out how photographic meaning might be manipulated. This task has sustained his work right up to the present, with a new series from 2015 exhibited at Galerie Max Hetzler, 21 November 2015 – 9 January 2016; any photographer still expanding their ideas at seventy years old is a rarity!

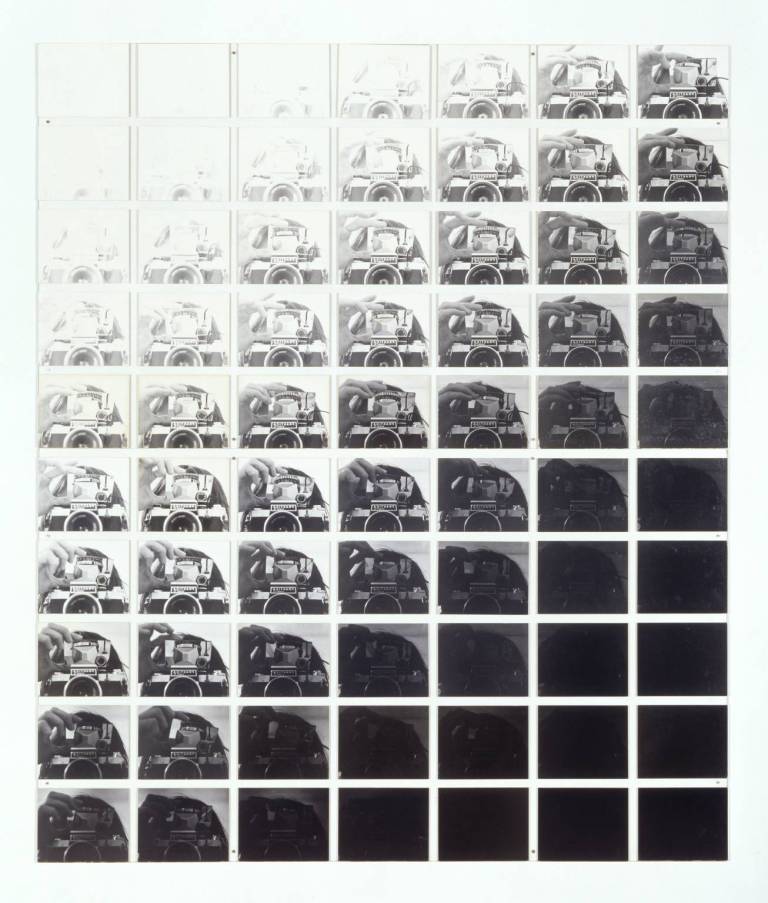

Key to most of his work are two early images. The first takes the elementary controls of the camera, and the camera itself, as its subject in a kind of self-portrait of the medium locked in a feedback loop. By holding a mirror above the camera Hilliard enables the viewer to see how each adjustment affects the exposure.

The grid, such as that used by Douglas Huebler in his 1969 Duration pieces or Bruce Nauman in Eleven Color Photographs, was a common device in art of this period. Hilliard turns it into a graph with variations of aperture and shutter speed arrayed around an ascending row of ‘correct’ exposures, but graduating toward overexposure (pure white) or underexposure in opposite directions, finishing with blank white or black at two corners

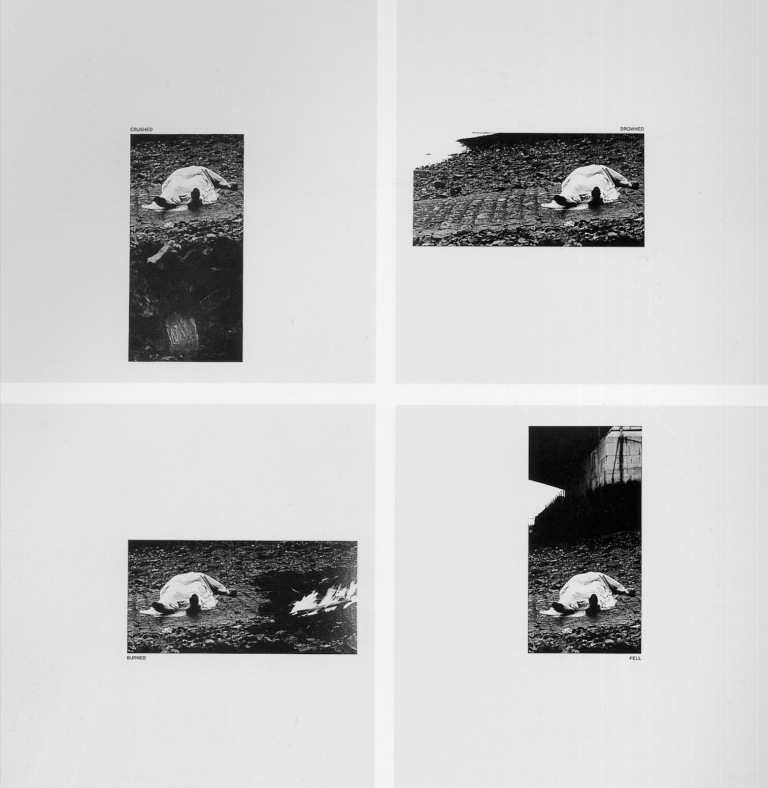

Cause of Death defies even our faith in the forensic, evidentiary use of the photograph. He presents four images with text next to each attributing a different cause to the death of the individual lying under the sheet; “Crushed”, “Drowned”, “Burned”, or “Fell”. All four prints are taken from the same negative and by cropping Hilliard modifies the context. Photographer Chris Steele-Perkins wrote that, in Cause of Death, “framing affects the way a photograph is read”, and that Hilliard provides the viewer with “elegant forensic evidence that, although the camera cannot lie, photographs tell different truths.”

Both of the above are didactic images, and in fact they are quite useful as a teaching aid in conveying how camera controls and darkroom production aid expression. This highlights the way Hilliard, like other conceptual artists, emphasises process; as repeatable exercises they satisfy scientific proof and simultaneously they deny the aesthetic preciousness of the unique art object.

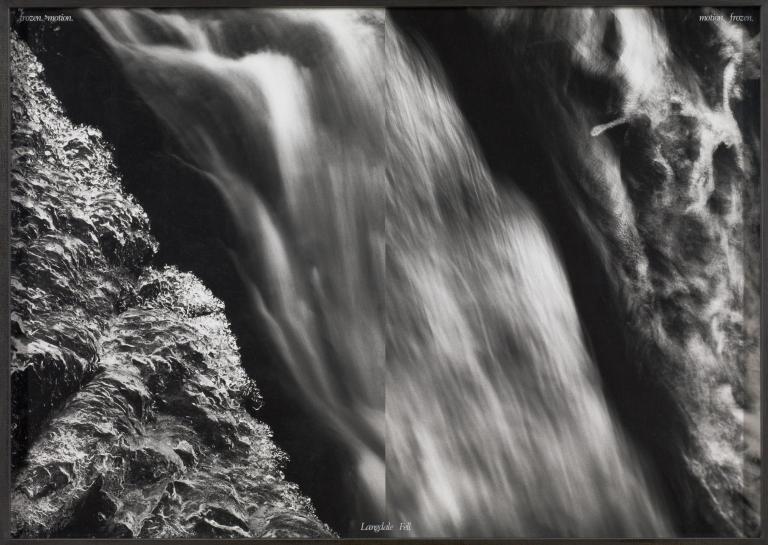

The work continues a self-referential strategy in series in which blur and focus are the variables.

Langdale Fell, Motion Frozen/Frozen Motion represents two views of a partially frozen waterfall discovered by the artist in the Langdale Valley, Cumbria. In order to photograph the left-hand panel, ‘frozen motion’, the camera set with a small aperture and slow shutter speed was fixed on a tripod, so that the flowing water registered as a blur, while the ice adjacent to it was clearly recorded. For the right-hand panel, Hilliard panned his hand-held camera at the speed of the flowing water. The result is that the frozen section of the waterfall registers as a blur while the moving water is arrested.

Critiquing the colour photography that was becoming predominant in magazines and advertising in the 1970s, Hilliard extended his conceptual explorations to include narrative, dramatisation and colour.

In He Sat Gazing At The Mirror of 1976, he continues the forensic theme in this scene which might be either that of a suicide or a murder, depending on one’s reading. The photographs are augmented with text with an equal ambiguity. The purple phrases might come from a tabloid newspaper or a cheap crime novel ; “He sat gazing at the mirror…Absorbing the oily red letters, his eyes slid down over the glass, paused, then flicked back to the beginning…All available evidence pointed to suicide (the second in the area that week).”

In this case a change of focus conveys the narrative; nothing else changes. It is the camera which has alerted us to the phenomenon of focus. Prior to the use of the camera obscura, there appear to be no representations of focus or soft focus in art, and very few right up until the advent of photography, probably because our eyes so quickly adjust to our attention that we do not notice it happening. The myopic or the hypermetropic were known to have faults with focus of course, but those blessed with good eyes failed to notice or account for accomodation, though it can be consciously controlled.

Other works by Hilliard of this period are narratives of faithlessness, betrayal, dishonesty, jealousy and other destructive emotions, so that his conceptualist interests might seem to serve expressionist intentions if it were not for his consistent use of them to examine the basics of photographic language, dissecting and concatenating, rejoining it, in the manner of a feminist deconstruction of a detective story.

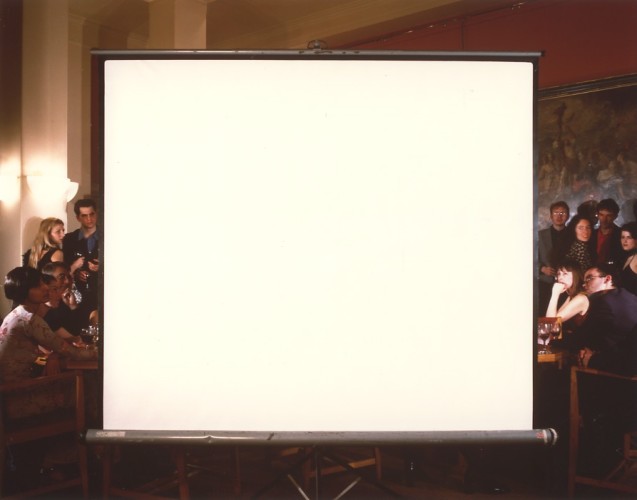

Another series blocks the view of the centre of the image with an object that is usually relevant to the narrative that we can only glimpse around its edges; these take to an extreme the suggestion often made to photography beginners who have a tendency to target their subject as if they were using a gun, to ‘use the edges of your frame’.

In 2002 Hilliard collaborated with Jemima Stehli (*1961, London) to produce This Picture. Stehli is well known for her conceptual play on self-representation and subjectification in her subject-actuated portraits of males, art-world figures, watching her take off her clothes in Strip.

Her remaking of Helmut Newton’s photographs of statuesque models, particularly his Here They Come (1981) and Self-Portrait with wife June and models (1981), using herself as the subject have all the hallmarks of homage including very exact restaging, but with quite the opposite intention and effect, though they are, in their fastidious remaking of the original, as much process pieces as any of Hilliard’s work. The collaboration was bound to be risky.

The result borrows from Hilliard’s ‘block-out’ pictures, but replaces a blank surface with one of Stehli’s own nude self-portraits in a mirror. In it she watches herself photographing herself and thus exercises complete control over her self-representation as a nude model. There is sufficient detail in the surround of This Picture to show that we are in the same studio, with Stehli, still naked, leaving by the door.

It appears that we are looking at a mirror image to which the black and white photograph has been adhered. Hilliard is occupied with making the copy, not with the camera set to one side, which is Stehli’s, but with a camera that is hidden from view behind the photograph. On its studio stand Hilliard’s camera is tilted, while in Stehli’s picture everything leans the other way. Hilliard’s concentration looks as if it is on the photograph he is copying, but as in Stehli’s Strip series, and in her version of Here They Come, a cable release snakes toward the door and may or may not terminate in Stehli’s hand.

Who has taken (in both senses) This Picture?

One thought on “March 29: Pictured”