February 21: Photographs “show in concrete objects the tangible visual magic of the real world.” Milan Kundera.

February 21: Photographs “show in concrete objects the tangible visual magic of the real world.” Milan Kundera.

Ivo Přeček was a key Czech photographer of the second half of the 20th century, who died on this date in 2006. He was founding member of member of DOFO (1959-75), the now legendary group of photographers from the Olomouc and Brno region. Přeček’s experimental techniques, including the photogram and photomontage, aligned with DOFO’s main focus on abstract and absurdist photography, in sympathy with a current in Czech art of the 1960s.

Members were George Gregorek, Antonin Gribovský, Jan Hain, Jaromir Kohoutek, Rupert Flower, Slavoj Kovarik, Zdenek Matlocha, Ivo Přeček, William Reichmann, Sapara Vojtěch and Jaroslav Vavra. Theoretician of the group was Vaclav Zykmund.

To understand avant-garde Czech art during this period requires some context. Czechoslovakia then was Communist, following on the jackboot heels of occupation by the Nazis in WW2. It was a time of upheavel with purges by the Stalinists of socialists with any wartime connection with the West, veterans of the Spanish Civil War, Jews, and Slovak “bourgeois nationalists”. Show trials resulted in extremely heavy penalties, including death for some.

A period of slow de-Stalinization followed through the 60s with hopes raised by the events of the 1968 ‘Prague Spring’ under Dubček who removed censorship and made moves toward liberalisation and democratisation, prompting a reaction and effectively an invasion by other Warsaw Pact countries which met determined passive resistance.

A Soviet crackdown dashed these hopes with the removal of Dubček in 1969 and a period of ‘normalisation’ of Soviet hegemony through the 70s and 80s against which resistance, including the shocking self-immolation on 19 January 1969 of student Jan Palach in Prague’s Wenceslas Square and challenges by intellectuals and artists, proved futile. These reached a critical point in the late eighties with the ‘Velvet Revolution’ and the fall of Communist rule in 1989.

Rumours, suspiciousness, paranoia, hopelessness and a sense of disempowerment pervaded society during these upheavals under a punitive surveillance state. Art, if it intended any protest or any political meaning, had to be adaptive and subtle, and Ivo Přeček’s, like that of others in the DOFO group, needs a double reading, an awareness of subtext, with this background in mind.

His simple image of a machinist’s locker indicates the elements of a private life which, while they might be locked away with the padlock and keys, are minimal; the basic pleasures of a Sunday off, eating, drinking and parenthood are all there is outside of the hours of work and its pressure to meet production targets.

Born 12 September 1935 in Olomouc, Přeček originally worked as a lathe operator, and did not become professional photographer till 1985 but had pursued photography since 1958 before joining the DOFO group.

Factory work is his experience that intensifies the meaning of these contrasty abstractions of the poetic significance of everyday objects; welding goggles and oxy-acetylin torches on a flame-singed bench, and bottles of beer cooling in the steelworks emergency eye-wash basin next to a guide to furnace temperatures from Poldina steel.

Somewhat more personally symbolic is this 1959 shadowplay of a nude figure and bird in a cage projected onto the rear of a curtain, the earliest work of Přeček that I can locate. It was made just after he returned to Olomouc from his military service and made in a more optimistic period.

Universal symbols of the captivity of love, they also represent a political frustration which is becomes more strident, more stark in a 1973 image of a pile of rusting bird cages, reminiscent of a stark cityscape on an open plane, not unlike that surrounding Olomouc, which is located on a rise amongst flat farmland.

It is in the monotonous surrounds of Náměšť na Hané, a market town in the Olomouc Region that Přeček made some of his most intriguiing series.

In the 1970s, pure photography began gradually to dominate his work, returning him to subject matter from the workplace and the systematic photography of bales of hay, gardens, and plastic covered greenhouses and the countryside around Olomouc. This approach was described by Antonín Dufek as ‘maximum evaluation of minimalistic subject matter’.

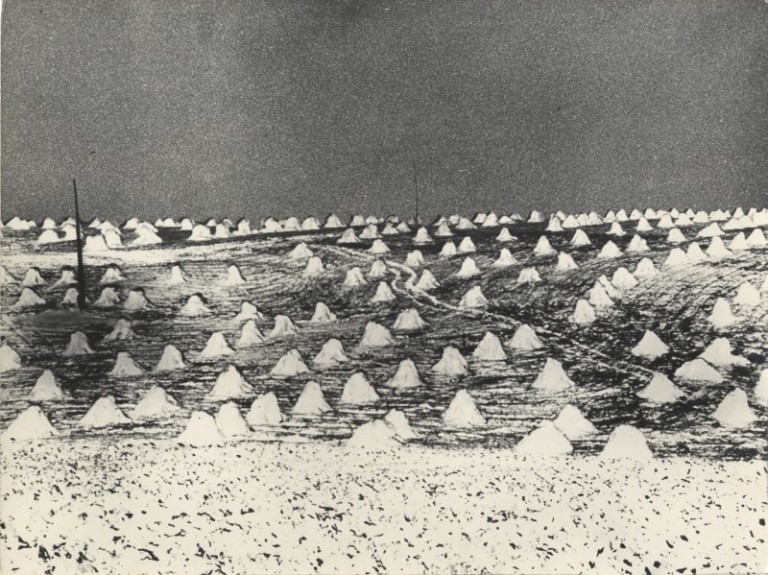

The stacks of hay bales are represented as ‘Pyramids’ in a series of that name. Seen as pyramids they may be read as monuments to the agrarian production targets and ever-increasing quotas imposed by the communist state, but for Přeček they present a formal challenge that in 1961 he approached with an experimental negative print in which one is not certain whether the scene represents a summer, or snowcovered winter, scene.

Returning to the countryside in the 1970s he finds that the mediaeval gathering of hay into stooks has been replaced by technologically more efficient machine baling, and that their geometry on a planar field starts to make sense for a topographic study.

By introducing a mirror Přeček begins to transform his subject. The small mirror reflecting the sky, placed so close to the lens that its contour fuses with the real sky, or introduces a sky scape amongst trampled and scattered bales that themselves have a cloud-like quality. Elsewhere the mirror breaks the horizontal monotony by interrupting the horizon itself.

The same analytic geometry is turned on his series ‘Humans’ with tragi-comic results.

Ivo Přeček also made three-dimensional objects and assemblages, though these seem to have been lost or are unobtainable in publications or online. However an idea of the application of his vision to sculpture can be gained from his still life photographs in which Přeček pays respect to Josef Sudek. From Sudek he learned to be receptive to simple subject matter in his nearest surroundings, with a lyrical accent and an emphasis on light, which he also often let play on semi-transparent or translucent objects, like a plastic-covered greenhouse, a window pane, wrapped bread, or by creating transparency through multiple exposure.

As writer Milan Kundera put it, the spirit of DOFO, so clearly exercised by Ivo Přeček, was “to show in concrete objects the tangible visual magic of the real world.”