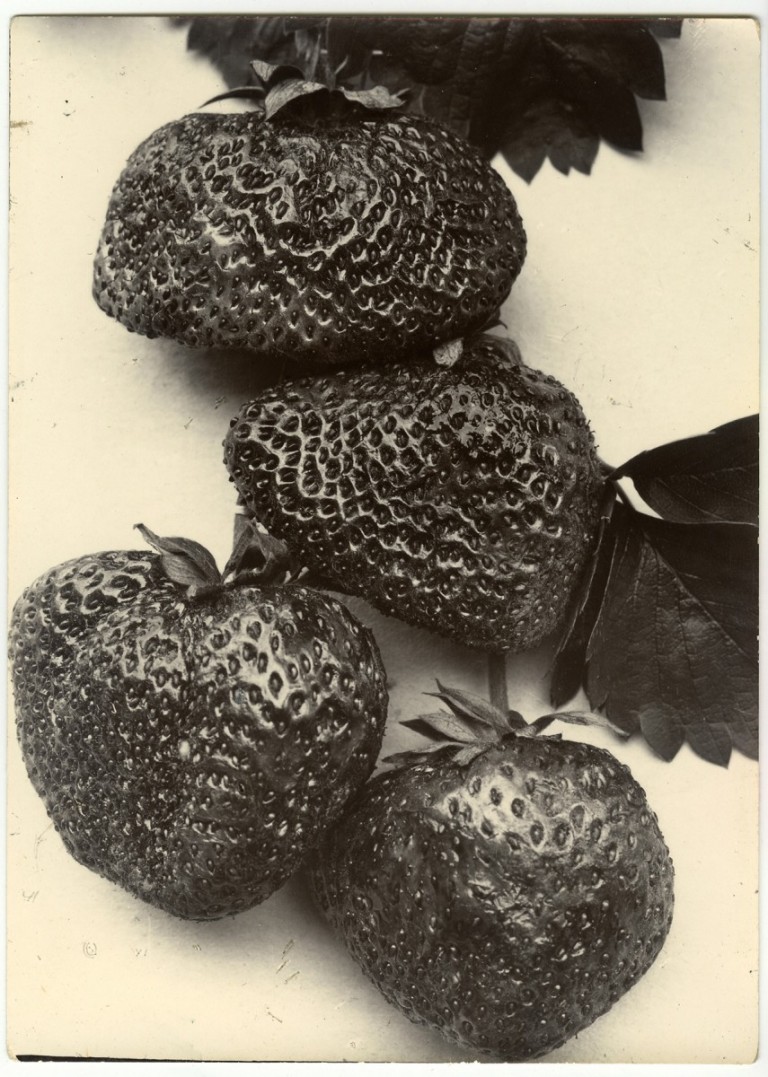

November 15: Charles Jones’ photographs of fruit and vegetables are celebratory. They fill our Spring day with joy.

November 15: Charles Jones’ photographs of fruit and vegetables are celebratory. They fill our Spring day with joy.

Here in Castlemaine, Australia, it is Spring, the weather this week ranges between dry and soaking wet, and between 10ºC and 30ºC. We’ve had the first decent rain since 2007 and in the bush the Chocolate Lillies are in such profusion as no-one can remember, we tread warily between rare orchids, lantern grasses nod their heads and the dazzling-yellow, sun-like Everlastings turn their faces toward the blazing Summer to come.

It is November 15, Autumn in the Northern Hemisphere, where on this day, Charles Jones was born in 1866 in England.

Jones’ photographs of fruit and vegetables are celebratory. They fill our Spring day with joy.

We’ve been harvesting broad beans since the end of October, but Charles Jones may not have seen his until April or early May. The title of this glorious image is Pea Quite Content. While any gardener would readily read that as the feeling of opening a pod in a crowded garden, it is actually the name of the variety of pea. This photograph comes to us from around 1900. It is beautifully and proudly printed from a glass plate negative and treated for warmth of tone with gold toner (traces of metallic gold plus silver chloride). The majority of the silver is unchanged, but the print is made more stable and permanent.

Charles Harry Jones was a gardener and an accomplished photographer. He made his studies of fruit as well as images of the private estate, Ote Hall in Sussex, where he worked during the 1890s until 1908.

Ote Hall is in the parish of Wivelsfield, near Burgess Hill, East Sussex and in 1573 came into the hands of the Godman family, who have owned it, with some breaks, until the present day. In 1881 it was acquired by Major-General Richard Temple Godman (1833–1912) and it was as his gardener that Jones carried out his work.

Godman was born in Park Hatch Surrey and joined the 5th Dragoon Guards and at the age of 21 went out to the Crimea where he took part in the charge of the Heavy Brigade at Balaclava (successful, unlike that of the Light Brigade) and was photographed there by Roger Fenton. Godman’s letters home throughout the war were published as A Cavalryman in the Crimea: Letters Home from the Crimea by Temple Godman (edited by Philip Warner, Windrush Press 1999). Married to Elizabeth Mary de Crespigny, he had 6 children and by 1871 he was lieutenant-colonel, eventually reaching the rank of major-general, before being appointed Colonel of his regiment on 17th Nov 1912 just before his death on 11th Dec 1912. In 1923, the house was bought by one Ernest J. Enthoven, who died in 1936, at which point his son sold the house (back) to the trustees of the Godman family.

Charles Jones’ photography was forgotten when in 1981 at an antique market in London author and photographic collector Sean Sexton purchased a trunk that contained several hundred turn-of-the-century photographs of vegetables, fruits and flowers; “With the Charles Jones photos, I knew I’d hit something really big. I was late for the market in Bermondsey [London]. I took one look and thought ‘works of art.’” The photographs were fastidiously annotated with the name of each plant followed by the initials C.J., although a few had the full name of the photographer.

Charles Jones’ photography was forgotten when in 1981 at an antique market in London author and photographic collector Sean Sexton purchased a trunk that contained several hundred turn-of-the-century photographs of vegetables, fruits and flowers; “With the Charles Jones photos, I knew I’d hit something really big. I was late for the market in Bermondsey [London]. I took one look and thought ‘works of art.’” The photographs were fastidiously annotated with the name of each plant followed by the initials C.J., although a few had the full name of the photographer.

Charles Jones’s granddaughter, Shirley Sadler, chanced to see Sexton in a televised interview. She added a little more to his personal history. She remembered her aged grandfather using some discarded glass plate negatives as cloches in his garden, so that may be what happened to his negatives, and as he left no notes, diaries, or writings she was unable to explain his reasons for making his photographs.

Besides his horticultural images, Jones did keep a photo album which Shirley Sadler passed on in 2004. It is possible that Jones didn’t compile the album himself, and it was his son, Eric Gordon Jones, who annotated it with titles and captions, though not in chronological order. Jones had photographed exciting events and discoveries, such as a local train crash, snake eggs and a vacuum cleaner, as well as the Godman family, and separately, their staff, entertaining themselves.

Ote Hall has since been renamed Great Ote Hall and is a function centre, but perhaps we can still discern in recent images of its surrounds some of the garden layout created by Jones.

While Jones’ images of plants have been compared with later works of Edward Weston and Karl Blossfeldt (some have even claimed him as a photo-modernist), his purposes were clearly different. Blossfeldt taught art and design at the Berlin Arts and Crafts School and his photographs of plants were intended for teaching resources, inspiring ironwork design especially. Weston and the f64 Group of the 1930s were purists who relished the clarity and sharpness of photography over the imitatively painterly qualities of the Pictorialists.

The sharpness and tonal qualities of Jones’ prints encourage us to regard them as fine art images, though these attributes are due to the materials and the large format camera he used, along with the way he isolates the plant subject from distracting backgrounds by inserting a white card or dark or light cloth behind them.

In 1873 Dr. H.W. Vogel had introduced the use of sensitizers (dyes) to increase the range of colour rendered by dry plates. The sensitizing chemicals had to be applied by the photographer until the first ready-sensitized gelatine silver bromide plates were sold in 1882/83 in Britain under licence by B.J. Edwards.

Jones’ orthochromatic (‘correct’ colour) plates, also called Isochromatic, were more sensitive into the green, and in part yellow, spectrum range than the earlier dry plate emulsions, rendering these in tones like that of panchromatic emulsions, but blues were still white in prints and reds and oranges were reproduced too dark. The result is tomatoes that are almost black, and note that the tomato leaf is reproduced as quite dark. These are qualities that lend strength to his compositions. It is interesting to note the surroundings reflected in their shiny skins; the photograph was made outside under the sky and close to a large building to the right.

Jones takes pains to ‘pose’ his subjects against neutral backgrounds (card or cloth) and it is this that gives some clue as to their intended use:

Black-and-white photographs became common in seed and nursery catalogues during the 1890s, shortly after Kodak introduced the first handheld camera in 1888. Seed merchants who used photographs distinguished themselves as more ‘honest’ than merchants whose catalogues contained misleading and exaggerated engravings. Many early black-and-white catalogue photographs were unattractive, presenting faraway, blurry, or dull views of plants and gardens and half-tone screens were often coarse. Gradually, however, photographs replaced lithographs and engravings.

To have an expert gardener, such as Jones, trained in photography and ‘on the spot’ to photograph examples of prize produce fresh from the garden, or still growing in it, was clearly the ideal for the seedsman to illustrate his catalogues. Was this how he learned photography, or was it already a hobby?

The photographer for the late 1890s catalogue on the left below has inserted a white backdrop behind this specimen of flowering plant. Jones (right) does likewise, using a dark backdrop to accentuate the lighter blooms. Clearly he intended to crop out, in printing, his assistant’s elbow which appears on the left from behind the cloth.

We can find the ‘Pea Quite Content’ that Jones photographed mentioned in a 1925 catalogue:

Carters Quite Content ( MAINCROP MARROWFAT to 6 ft.). This grand Pea, which has caused such a stir in the horticultural world, is the outcome of a cross between ALDERMAN and EDWIN BECKETT. In general character resembles the former but the pods are considerably larger than either parent. In our own trials it has amply demonstrated its wonderful superiority and when exhibited in the open class at Shrewsbury it easily secured the First Prize, and was pronounced by leading exverts to be without doubt the best Pea ever seen. It is exceedingly prolific and the pods hang mostly in pairs. [‘marrowfat’ refers to a crop which produces large peas intended for drying and storing for use in soups etc.]

Carters Quite Content ( MAINCROP MARROWFAT to 6 ft.). This grand Pea, which has caused such a stir in the horticultural world, is the outcome of a cross between ALDERMAN and EDWIN BECKETT. In general character resembles the former but the pods are considerably larger than either parent. In our own trials it has amply demonstrated its wonderful superiority and when exhibited in the open class at Shrewsbury it easily secured the First Prize, and was pronounced by leading exverts to be without doubt the best Pea ever seen. It is exceedingly prolific and the pods hang mostly in pairs. [‘marrowfat’ refers to a crop which produces large peas intended for drying and storing for use in soups etc.]

Their photograph has none of the poetry of Charles Jones’ image of the same variety, but a neighbouring image from the same catalogue shows how closely his photographs match better examples of the genre:

Jones has been the subject of a book by Robert Flynn Johnson and Sean Sexton with a preface by Alice Waters, Plant Kingdoms: The Photographs of Charles Jones (Smithmark Publishers, New York, 1998), and of museum exhibitions at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, California, in 1998, at Le Musée de l’Elysée, Lausanne, Switzerland, in 1999 and the Chicago Botanical Gardens, in 1999.

Charles Jones’ vintage photographs can be found in the collections of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Achenbach Foundation for Graphic Arts, San Francisco, the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

2 thoughts on “November 15: Primavera”