Paul Lambeth’s exhibition Within Sight is currently showing at the Eureka Centre in Ballarat, 10.00am – 5.00pm daily until Sunday, 1 March 2026 (entry included in $5.00-$7.00 museum admission fee)

Paul Lambeth’s exhibition Within Sight is currently showing at the Eureka Centre in Ballarat, 10.00am – 5.00pm daily until Sunday, 1 March 2026 (entry included in $5.00-$7.00 museum admission fee)

The viewer puzzles; “Within Sight? Perhaps, but what am I looking at?” Such a vibrant variety of imagery demands examination before we can comprehend its content.

A shop assistant in his late 20s, perhaps a ‘new chum’ from Melbourne, asked what I’d been doing, and when I said I’d spent the morning walking the hills out of town, replied; “Oh, were you in nature?” I venture that this primly reverential and cringeworthy American import means that I was indeed, “out in the bush”.

‘The Bush’, as Ged Martin asserts (Australian Literary Studies, vol. 6, no. 4, 1974), is an expression coming, not as some assume, from the Dutch bosch through the Cape Boers, but carried here (and reported in 1798 records) by convicts, and poor rural or working-class settlers speaking a sub-dialect of English, or thieves’ ‘flash’ argot. Their superiors referred to ‘woods’ before gradually adopting the upstart convict term. Many places are named ‘Bush’ in England; Harlow Bush and Hawkesbury Bush in Essex, and Shepherds Bush and Bushy Park in Middlesex; mixed woodland and scrub, open country, common land, wasteland, thickets, patches and peripheries. There, ‘bush’ was a toponymic for rough ground, where a man who is poor was said to live “at Bushy Park”.

It proved an apt idiom for the British cast involuntarily into Australia. To them it was hardly picturesque; it was “bush”, rough, unformed, chaotic, trackless and dangerous. In Australian culture, in Banjo Patterson’s poetry or paintings of the Heidelberg School, the bush became revered as a national ideal; never a fixed geographical location, but a charged idea.

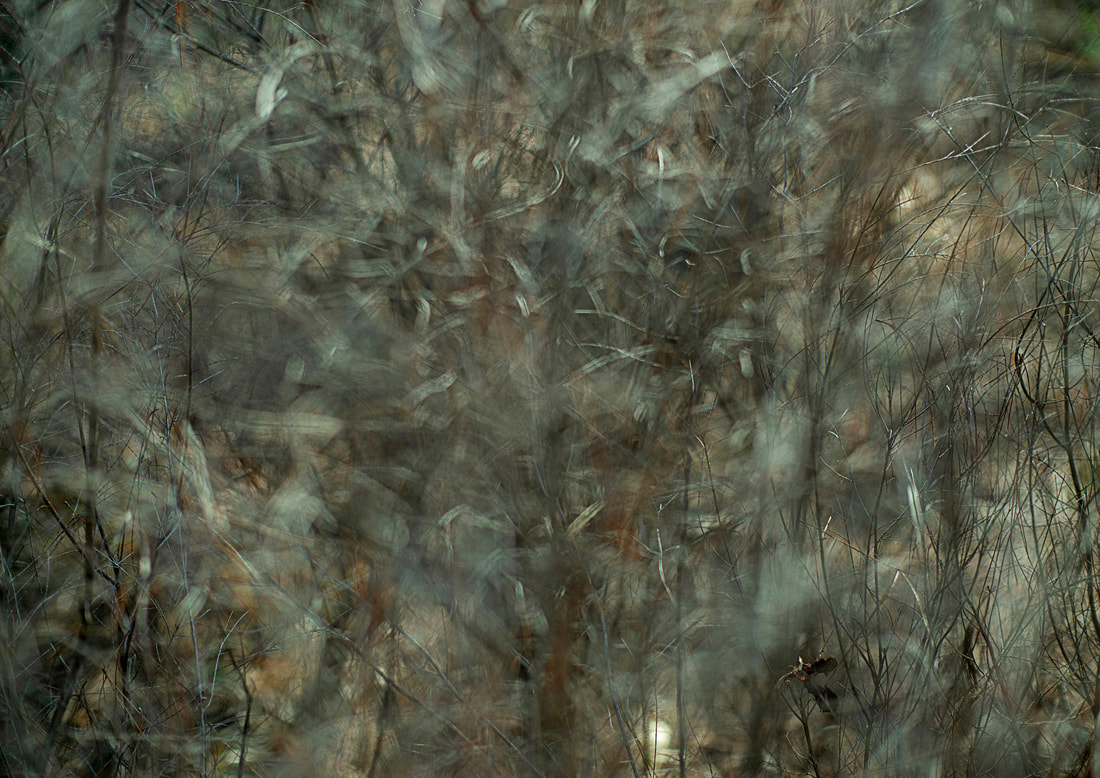

Where then is The Bush in Paul Lambeth’s images? We’re never standing back— it is right at our feet. He presents not a mythologised landscape, but a ‘sight’. These pictures develop a phenomenological engagement, through an intense sense of touch as well as of vision. Paul’s lens reaches into the depth of the tangle, the layers. One image is strikingly skeined like a Jackson Pollock, scribbled like a Cy Twombly, in an all-over composition of brittle twigs and tendrils hovering between soft grounds forward and behind. Consequently, some label his work ‘abstract’, but he insists he is not attempting ‘photographic paintings’, but making factual and descriptive imagery. He is with Maurice Merleau-Ponty (Phenomenology of Perception) in knowing that “truth does not inhabit only the inner man… man is in the world, and only in the world does he know himself,” a claim perfectly mirrored in Lambeth’s dedicated attentiveness.

Paul, in making these pictures, is indeed ‘in nature’ to the extent of reclining on its breast. A portable festival chair that he carries on his excursions supports him low to the ground. Patiently he waits, absorbed in his surroundings. At that range focal points hover in space before us, pulled toward our eye through his lens, one selected from a box of cast-offs, a 55mm f1.2 or a 135mm, and connected with extension tubes to his 2013 model 36Mpx Sony a7R digital camera, an extension of his embodied perception.

These are not experiments. Paul is a photographer of long standing, trained by John Cato and Paul Cox at Prahran College in the 1970s in a course that for graduates provided, by treating the medium as an art form, entry into any field. That included, for Paul, work in a local studio, in a cine lab, a government department, teaching at SMB in Ballarat, as Director at Arts Mildura and exhibiting along the way. Amongst his many adventures and occupations—drifting down the Murray River on a home-made raft, crewing a fishing boat off Western Australia, living on a small island in Greece, following the path of explorers Burke and Wills—Paul was a medical photographer at the Eye and Ear Hospital, imaging the passage of dyes through patients’ retinal veins.

There is an inspiration for this series. In effect, it is our human eye we see here as nature looks back at us. We are engaging with something sentient, that sees us in return, an organism not restricted to one plant form but entwined between them in an ecological whole, of which these vignettes are an impression. Merleau-Ponty writes of this mutual encroachment or interweaving of the seer and the seen, which Lambeth realises so sensitively.

That haptic sense of the eye, for which in the dark we substitute our hands, causes these natural forms to touch us, almost to brush our eyelids. Textures and protrusions then mist into un-focussed fields of soft colour stretched, melted and distorted by the lens’s shivering aberrations. Paul’s innovation of sometimes imaging through a concave shaving mirror in one instance renders sharp two arcs of soil, cracked and mossy, that bracket, above and below, a preening of fluffy white down dropped by a cockatoo, caught spider-like in spider’s webs and hovering in the breeze.

More delicate still is the calligraphic gesture of another feather poised on a glimpse of sunlit forest litter at the exact point of focus that details its intricate barbules against blurred depths. Those fishbone forms reappear as the outreaching bronze palm of dead bracken that has caught a green leaf, reflected as a visual echo in a blue ghost hovering beside. Soft and clear blend sumptuously to delight the eye, establishing a radiant interplay.

A Brobdingnagian drama was set up when an uprooted sprig of now desiccated grass, on its bare roots, was cast by fickle winds against granite boulders. Incredibly, they are actually mere pebbles.

In another image dry rustling grass strands become stretched as if reflected across the surface of water, or submerged. Likewise, a pair of clam shells float into focus within an optical gyration, before they prove to be microscopic, the lids of trapdoor spiders’ nests.

There is an organic reaction underway within sight throughout this series. Growth, evolution, and decay act out before our gaze; a fallen blue-grey eucalyptus leaf appears to vibrate and dissolve into the soil, which itself is being absorbed by the creeping magenta of a colonising plant.

This is not quietus, but quietude that Paul shares here, giving us living hope for nature…

“Rarely am I drawn to grand or dramatic scenes, I focus on understated moments and hidden detail: the way light moves, the stillness of a dry creek bed, the interplay of wind and grasses. These details often hold a quiet power, inviting a slow and attentive way of seeing.”

Beautifully written James with great sensitivity and insight … how large are the prints please? when is the exhibition on until? thank you so much! Marcus

LikeLike

Thank you Marcus, and for a chance to wish you a rewarding 2026 … Paul’s show is on till 1 March, and the prints on display are quite large, I guess 1-1.5m wide. James

LikeLiked by 1 person

Happy New Year to you James!

I hope 2026 is good for both of us 🙂

LikeLike