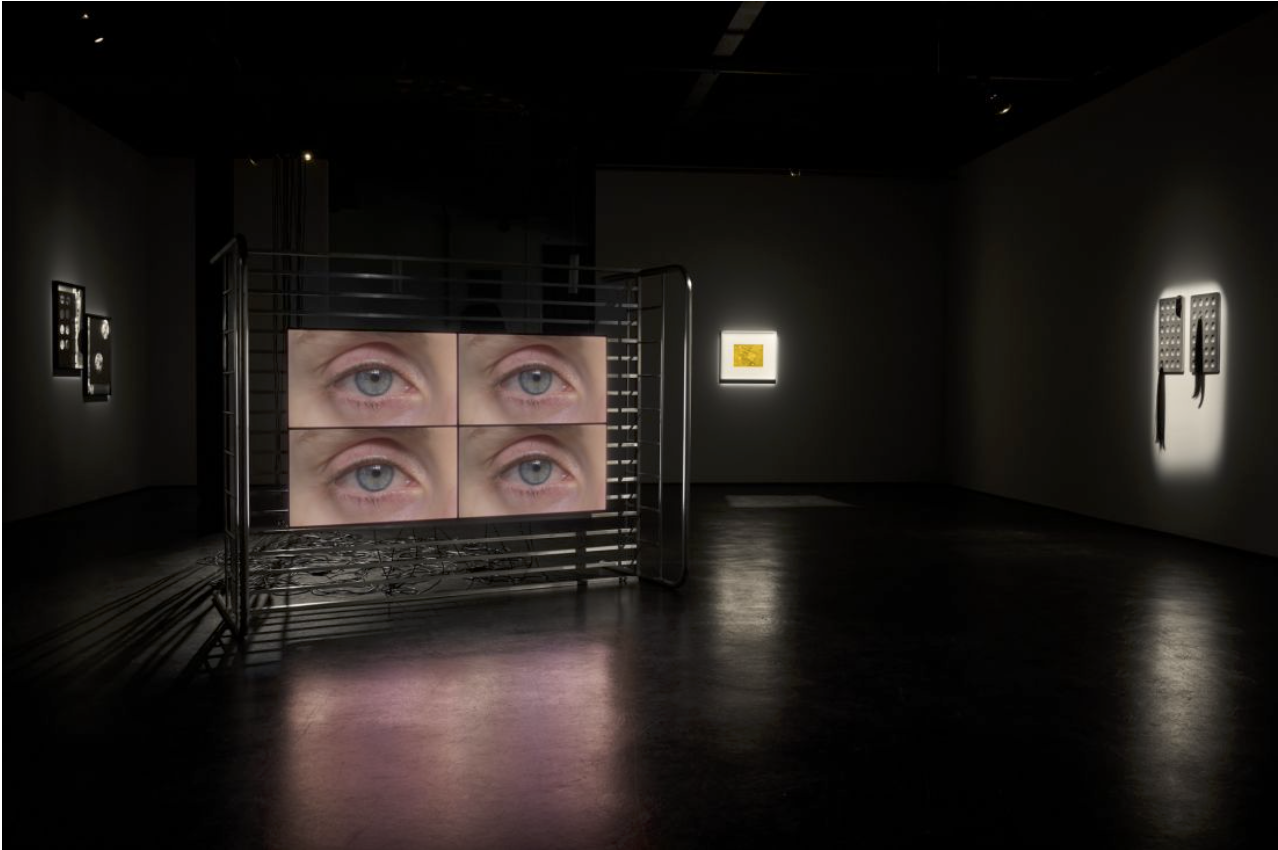

Multidisciplinary artist Christina May Carey’s Continuous Present closes today at Laila gallery, Sydney, in which the floor was dominated by a pair of restored doors, their hinge cut-outs still evident, of lovingly sanded and stained, antique teak. Surprisingly they are pierced by CNC-cut circular forms, and custom legs prop them up so that these alterations can be better seen on entering the show.

Multidisciplinary artist Christina May Carey’s Continuous Present closes today at Laila gallery, Sydney, in which the floor was dominated by a pair of restored doors, their hinge cut-outs still evident, of lovingly sanded and stained, antique teak. Surprisingly they are pierced by CNC-cut circular forms, and custom legs prop them up so that these alterations can be better seen on entering the show.

One might say, if one wanted a pair of doors like this, that their original function has been destroyed though, even originally, they would be too low to serve on a door frame and rather large for a cupboard.

For a photographer, the perforations or punctures recall those made by Roy Stryker in Farm Security Administration-commissioned negatives of which he did not approve, which destroyed, or ‘killed’, them. Viewers soon discover that holes have likewise been punched into Carey’s wall-hung works!

Christina May Carey’s practice spans photography, moving image, sound, sculpture, and installation; investigations into how time, attention, and perception are lived rather than represented. To achieve that she works through iterative processes, serial structures, and carefully staged environments that viewers may understand only through engaging with their duration, uncertainty, and sensory imbalance.

Carey evokes and invokes interior states—sleep and waking, hypnagogia, focus and drift, coherence and fracture—using repetition, looping, layering, and material restraint so that meaning emerges through cumulative manifestation rather than through linear progression.

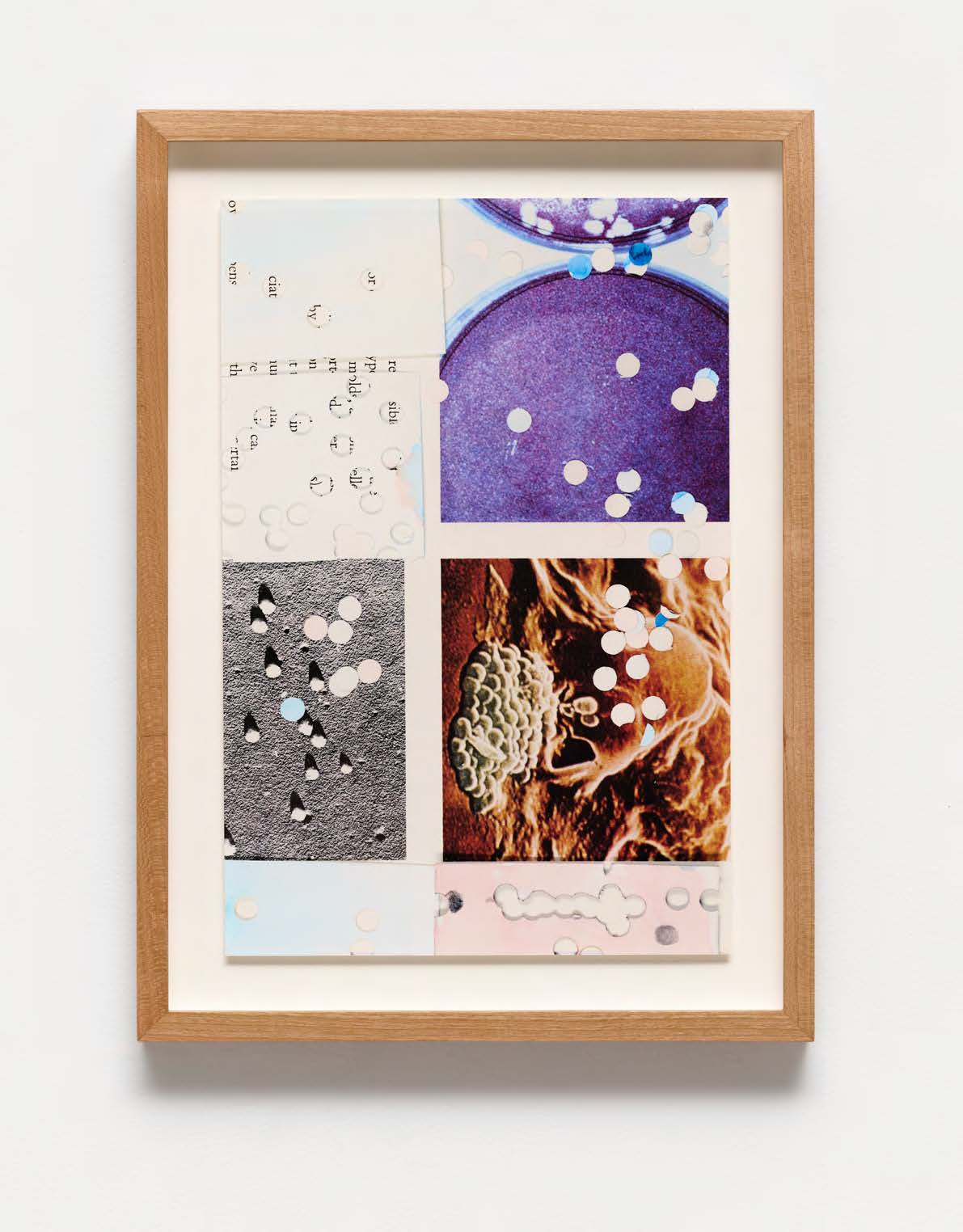

In Continuous Present (Laila, Marrickville, 5–20 December 2025), photographic and sculptural applications of repetition become both method and subject, discipline and devotion, while introducing deliberate disruptions—holes, overlaps, and doubled images—that fragment and confound stable vision, distorting it through the conceptual lenses of Blind Spots, Diplopia, and Divergences.

This gesture can be productively read alongside a longer history of photographic intervention, including Roy Stryker’s well-documented practice of punching holes through unwanted Farm Security Administration negatives during the 1930s. Stryker’s hole-punches were acts of editorial authority: irreversible interventions that effectively “killed” images by bleeding their future circulation.

Whether or not that historical reference is intentional, Carey’s punctures invert that logic. Rather than closing down an image, they open it. The hole becomes not an erasure but an aperture, giving other images, layers, or time-frames entry. In this reading, Carey’s spots are not blinded failures but reminders that vision is always partial, that repetition does not guarantee clarity, and that attention must become imagination to retrieve what escapes it.

Fragmentation is its most forceful in affect in Carey’s series of Divergences which appear on walls surrounding the sculptural work Everything’s the Same, Everything’s Different which rears up from the floor below those images—a metaphoric trapdoor into the exhibition, and its template. Examination of the text and images, seen in her pigment print copies of collages shot through the punch-holes, one finds hints of a physical threat; spots as signifying the deadly spread of viruses and cancer.

In fact, the text, and the punctured images of Divergences, do have history. They are sourced from page 581 of a nearly 45-year-old, moth-eaten Oxford University Press textbook Medicine: An Illustrated History (still on the shelves, as Trove records show, in 44 Australian state and university libraries) which surveys historical medical thought and old debates on cancer causation: the supposed embryological, microbial or viral origins, and the hypothesised conceptual progression of teratomas, microbes, Rous tumour-inducing viruses in animals, against missing evidence for human virus-caused cancers (before HPV/EBV were confirmed).

Thus the piercings become a vital punctum entirely consistent with Carey’s artistic practice concerned with latency, residual knowledge, and temporal overlaps, but read this way the holes may signify viruses; see how the blank purple Petri dish in Medicine‘s illustration of Polio virus, in Careys’ Divergences (2), is populated with her hole punchings and their ‘chads’…or think of that black spot, the melanoma…

Carey’s images are riddles—and may be riddled with cancer or invaded by viruses—but can an artwork be ‘solved’, even by knowing its ingredients?

Lucy Swan’s Same same but different, the introductory essay in the catalogue for Continuous Present is not at all about disease, but repetition, which is rarely granted the dignity of moment, but is dismissed as inertia or failure to progress:

Repetition is often understood to be something negative; sameness; the result of a lack of imagination; stagnation; of being boring; inhibited; uptight; controlled; mindless. Which of course, it can be, if we’re thinking about being repetitive. But repetition done with awareness, with presence, with intention, becomes something else. It transcends the mundane and mindless and becomes a discipline; a tool; ritual; devotion; a practise.

In artistic discourse, it is often tolerated only when redeemed by system, irony, or conceptual rigour. Yet across the last century, some of the most searching modern and contemporary practices (Agnes Martin, On Kawara, Hanne Darboven) have returned insistently to repetition—not as redundancy, but as a mode of attention, a structure of endurance, and a way of inhabiting time purposefully. Christina May Carey’s exhibition extends this lineage, while also troubling it. The works do not simply affirm repetition as dedication or discipline; they expose its blind spots, double visions, and points of divergence. To encounter the exhibition fully is to see through eyes that do not quite align, that hesitate, overlap, and recalibrate.

Lucy Swan draws on Simone de Beauvoir, Gilles Deleuze, Gertrude Stein, and feminist philosophies of practice, to reframe repetition as an intentional, embodied process rather than a mindless one. Repetition, she argues, becomes meaningful when approached with awareness and presence—when it is practised rather than merely tolerated. Carey’s work resonates closely with this position, while also extending and complicating it. Through visual strategies—most notably puncture, layering, and doubling— Gertrude Stein’s notion of the “continuous present,” a temporal mode in which “everything is the same, everything is different,” meaning accrues not through narrative development but through rhythmic insistence, recurrence, loops in syntax.

Here Swan steps into the exhibition herself. Hanging between Divergences (1) and a door which it matches in height is 1001 Over Simplifications, her collaboration with Carey. From the distance it might be mistaken for a piano roll, the late 19-century ‘punch-card’ for the pianola which repeats its music exactly while moving the keys uncannily, as if the Mechanical Turk operates inside.

Printed on the scrolls, in the same all-caps as the lyrics on a pianola roll, is a list of aphorisms, terse truisms, glib oversimplifications—”Not everyone sees colour in the same way’—which condense complex realities and philosophical issues into brief, catchy statements of the kind that so often adorn kitsch motivational posters—so often mere justifications in fact—that are here formatted with right and left justification so drastic as to stretch apart the words of some of these timeless phrases so that, again from a distance, the text is punctured and ruptured and like the surrounding perforated images.

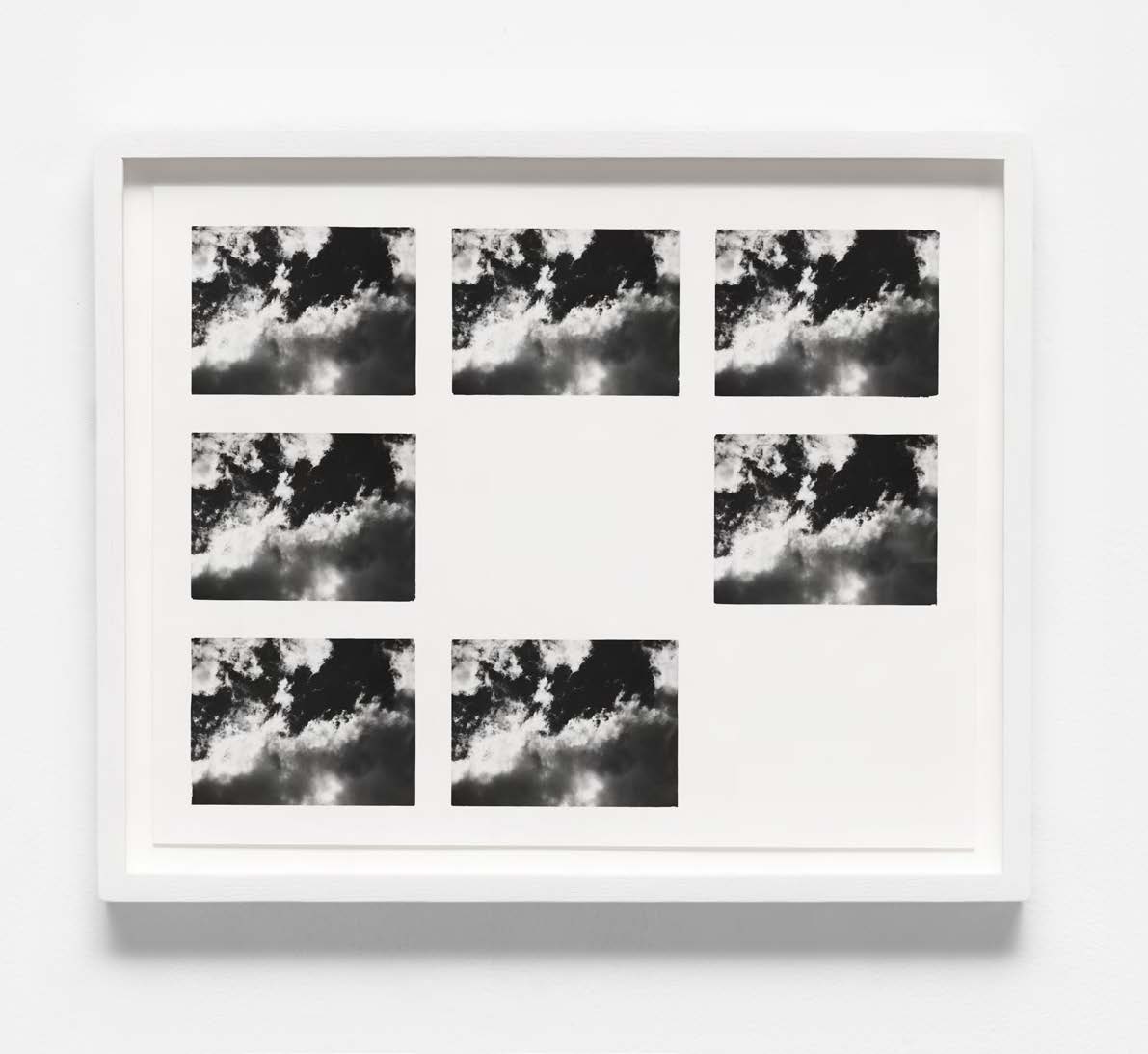

Carey’s serial photo-based works— Divergences, Blind Spots in the Linear Trajectory, and Diplopia—operate to a formal constraint in which scale, framing, exposure, and presentation remain consistent for each. Difference emerges not through a sudden revelation, but through accumulation—the viewer is compelled to linger, to compare, to notice subtle deviations that only register through sustained looking. This is repetition as duration rather than repetition as replication. Carey’s images remain equivocal. They do not confirm stability so much as register perceptual uncertainty.

Clouds can move so slowly—“everything is the same” but no, “something is different”—a motion so subtle that we must concentrate to perceive it. Here the viewer is forced into labour, to stare long and hard at the Blind Spots in the Linear Trajectory prints—each painstakingly printed in the darkroom in exact grids on one sheet—until one becomes convinced that there is no difference—but wait, do the white clouds ‘fray’ the corners here and there as the mask shifts incrementally between each exposure? Interrupting duration and our close attention, the missing frames ‘blink’.

Swan’s essay draws on Simone de Beauvoir’s distinction between immanence and transcendence to argue for the value of repetitive, maintenance-oriented labour. Historically assigned as feminine and domestic, ‘immanent’ work, habitual work, is reframed not as a dead end but as a transformation. There is no transcendence without repetition; no future without sustained attention to the present. Carey, by using analogue photographic process in Blind spots materialises this argument. The works are not singular gestures but the result of iterative labour: repeated exposures, adjustments, and reworkings. This is photography not as capture but as practice—more a meditative ‘writing’ of the images than momentous. The product of the camera becomes an object of return rather than extraction.

At the same time, Carey’s work acknowledges the strain of this commitment. The titles alone— Blind Spots, Diplopia—signal fatigue, perceptual overload, or misalignment. Repetition here is not romanticised. It is lived through. If repetition is devotion, it is also endurance; if it is grounding, it can also be destabilising. A blind spot is not an absence of vision but a structural condition of seeing—the point at which the eye cannot see itself seeing.

Silver gelatin print on fibre matte paper (multiple exposures). Hand-finished white lacquered oak frame, raised float mount, ArtGlass AR70, 33.2 × 40.8 cm. Edition of 3 + 2 AP

Silver gelatin print on fibre matte paper (multiple exposures). Hand-finished white lacquered oak frame, raised float mount, ArtGlass AR70, 33.2 × 40.8 cm. Edition of 3 + 2 AP

Diplopia, or double vision, occurs when the eyes fail to coordinate. The result is not simply blur but multiplication in which two images occupy the same perceptual field. In Carey’s Diplopia series, made again by masking multiple darkroom printings of the same image on one sheet, a profile hovers in depth, at either side of the plane of a mirror, which itself is unseen other than by inference. Randomly scattered confetti of chads from the hole-punch interrupt the neighbouring prints, some of which are exposed more heavily, with the result that our eye cannot settle, except momentarily on points of focus in the mid-tone copies, only to find them obliterated in the dark.

This ‘twinning’ resonates with Carey’s collaborative exhibition “Gemini ” (with Aaron Christopher Rees), where repetition and cyclicality are technologically mediated to expose ecological disorientation in 24/7 capitalist time. In that context, loops and repetition function as coping mechanisms under conditions of exhaustion. Read back into Continuous Present, diplopia becomes a way of understanding repetition itself: never singular, always carrying the residue of what has come before. Repetition here is not a return to the same, but a holding together of misaligned temporalities—the present act of making and the accumulated weight of having made before. Carey’s work does not resolve this tension; it sustains it.

For Swan, this closely aligns with Deleuze’s insistence that repetition is not opposed to difference but is its condition.

The punch-card, the perforated device, in Carey’s sculptural and photographic works may be an additional register, a reference to early computation, bureaucratic systems, and mechanical memory—structures defined by repetition, encoding, and control. Carey’s work does not illustrate these systems, but it can be read as invoking their logic. The hole becomes both a unit of pattern and of permeation. By placing this aesthetic within works concerned with presence and attention, Carey introduces a tension between devotion and the system, between bodily rhythm and mechanical/electronic repetition. This dimension extends beyond the scope of Swan’s essay, which focuses primarily on embodied, feminist, and philosophical models of practice, and places Carey in dialogue with feminist and maintenance-based practices such as Mierle Laderman Ukeles’ Maintenance Art, where repetition becomes a political stance against productivity-driven models of value. But Carey’s work may suggest that repetition today is not only cyclical or devotional, but also systemic—shaped by technologies and structures that exceed individual intention.

Howardena Pindell is celebrated as an American artist of conceptual Pointillism. Experiencing as a child in segregated America, the red circle as as “a scary thing”, a mark on tableware used to serve people of colour in cafes, she exorcised her relationship with the shape by “punching holes” and ‘painting’ with the resultant chads. In Melbourne we have been inundated with dots…Yayoi Kusama’s covered even the trees on the St Kilda Road frontage of our National Gallery. But where does this Carey’s exhibition stand in relation to an Australian stream of physical interruptions to photographic reproduction and repetition? We might turn to Marcus Bunyan’s account the Museum of Australian Photography exhibition Cutting edge: 21st-century photography, held ten years ago, 26 November 2015—21 February 2016, in particular Derek Kreckler’s sculptural rendition of temporal extractions from a beach scene.

In Jo Scicluna’s more purely photographic body of work When Our Horizons Meet the circle becomes a keyhole that connects new to remembered, horizons…

…while more profound, more vertiginous, is the black-velvet-lined lacuna cut into First Nations artist James Tylor‘s landscapes—an intervention he intends as a form of censorship, like the black rectangle covering the eyes of a nude in a 1960s ‘skin mag’—only in this case it covers the greater obscenity of genocide.

Carey’s blind spots are not smooth cycles but shaped by bodies, systems, fatigue, and care. If Swan’s essay frames repetition as diligence and self-determination, Carey’s work suggests its complications. Together, they offer a refined practice that is not obsessive, sentimental, heroic nor resigned, but which bestows a fulsome attention to its ideas and making.

Christina May Carey lives and works in Naarm/Melbourne. In 2015 she undertook a Foundation year in Art and Design at Central Saint Martins, London then completed a Bachelor of Fine Art (Honours) at the Victorian College of the Arts in 2021. Carey has participated in shows at the Kings ARI, VCA Art Space, Hyacinth, George Paton Gallery and at Science Gallery Melbourne. In 2019 she was commissioned by The University of Melbourne to contribute work for the 757 Art Project, and in 2020 she was awarded the Majlis Travelling Scholarship.