This is the perfect place for rumination, and that rather than reminiscing, which, while it also entails remembering, is more effective in a direct conversational exchange, not as a remote and delayed reading of a post, to which any response requires considerable effort.

This is the perfect place for rumination, and that rather than reminiscing, which, while it also entails remembering, is more effective in a direct conversational exchange, not as a remote and delayed reading of a post, to which any response requires considerable effort.

To ruminate is to chew things over, like a ruminant (the goat is an appropriate simile since I am a Capricorn) whose digestive processes involve fermentation and re-digestion for the maximum extraction of life-giving goodness; one chews on something rather than let it chew oneself.

The rumen here is an exhibition.

While I was serving as head of the School of Visual Arts at La Trobe University in Bendigo, Crosstalk was an idea I had for promoting our regional art school on Bendigo and Mildura campuses to the rest of the University. I had found, during my attendance at monthly University Council meetings, that very few other staff were aware we existed, apart from those among our Faculty, like Theatre and Drama lecturer Meredith Rogers, whose history included formative associations with the Women’s Art Register and George Paton Gallery, or the even more readily collegial Norie Neumark, then Chair and Professor of Cinema and Media, and lately Honorary Professor at the University of Melbourne.

The meetings always took place at Bundoora and required travelling, usually by public transport to preserve our slender budget, to a campus that from my perspective was also remote—in the far northern suburbs of Melbourne, two early hours away from North Central Victoria by train and bus. Raising our particular triumphs and problems by negotiating to insert items in the agenda bought little more than a cool, polite acknowledgement, and it was more effective to try to resolve them with the Dean at our weekly faculty meetings.

How then was I to put us on the map? That was becoming more urgent as funding diminished. In richer times, previous Heads of School the printmaker Jennifer Marshall, a sterner, more effective leader than I, and her predecessor, while building funds were available, had achieved a miracle, milking some millions from the University for what was always referred to as a ‘downtown presence’, a building in the ‘arts precinct’ the Peter Elliot-designed La Trobe Arts Institute that still functions (despite the currently much diluted Visual Arts courses) opposite the Bendigo Art Gallery, albeit not in Melbourne. Nevertheless it provided us a prominent purpose-built exhibition space for our postgraduates, art staff and our associates.

The question was how to exploit that in such a way that Bundoora heavies and bean-counters would be made more aware of us, and of our value to the academic ambitions of the University? Art being about everything—any subject at all—meant that, inherent in that fact, connections were to be made with the specific interests among other disciplines of the University.

The slogan becoming then current—later peaking in 2021—’art practice as research’ needed to be given status in the institution, I felt, and wondered if that might be achieved by each member of the art school expressing how their own practice constituted research, and how it related to researchers in a corresponding field, and then making contact with such researchers in the University? Still-life paintings must surely hang on the walls of ecologists and plant biologists. Pottery? Well ceramics was an area of study for La Trobe’s Centre for Materials and Surface Science. The graphic designers and photojournalists might raise interest in their work among the academics of the Bachelor of Media and Communication that was first offered by La Trobe that year, in 2008.

It was a flop. In fact only three of the nine permanent staff members made any contact with a researcher at the flagship campus. Were the others suffering impostor syndrome? Perhaps they were just lazy…the preparation for the exhibition spanned the summer break, after all, and the exhibition coincided with the return of students in March, but there was plenty of time, and cars were available for trips to Melbourne. Perhaps I had not expressed the aim of all this clearly enough, because one went to a researcher at another university.

Today, seventeen years later, and though this end of the telescope, the politics are trifles dwarfed by a personal affirmation that stays with me. At the time, having finished my PhD four years earlier, I sought someone at the main campus who might share my interest in my subject, human visual perception as analysed by the camera serving as an analogue, interpretation or equivalent. They weren’t to be found among Health Sciences staff, but the physicists suggested I ring Psychology, and that is where I sought Professor Ross Day and found him, as I remember it, on the second floor of the Heath Sciences’ George Singer Building amongst his laboratories.

I was then 57 so to me Day appeared very old, and in fact he was eighty, but still lively, kind and approachable, a tall shambling figure still with a mop of curly hair. Still nervous, I was about to unfurl on his office floor the 3m x 1.2m black and white images that I had exhibited at Bendigo Art Gallery some years earlier, and the digital colour landscapes I was then working on, but seeing their size he suggested we move into one of his laboratories. There, he walked quietly around the prints while I explained their production.

I told him how I had discovered his interest in human perception and illusions. He explained how he had developed his ideas through devising experiments that would test, for example, visual perception against the other senses, in one case placing a swinging garden seat at the centre of a room and surrounded by curtains suspended from a large rig. Swinging or spinning the curtains would induce the sense of movement in subjects; though motionless on the seat, they felt it move in the opposite direction to the trajectory of the curtains. He considered, he said, that a similar effect was occurring in my images.

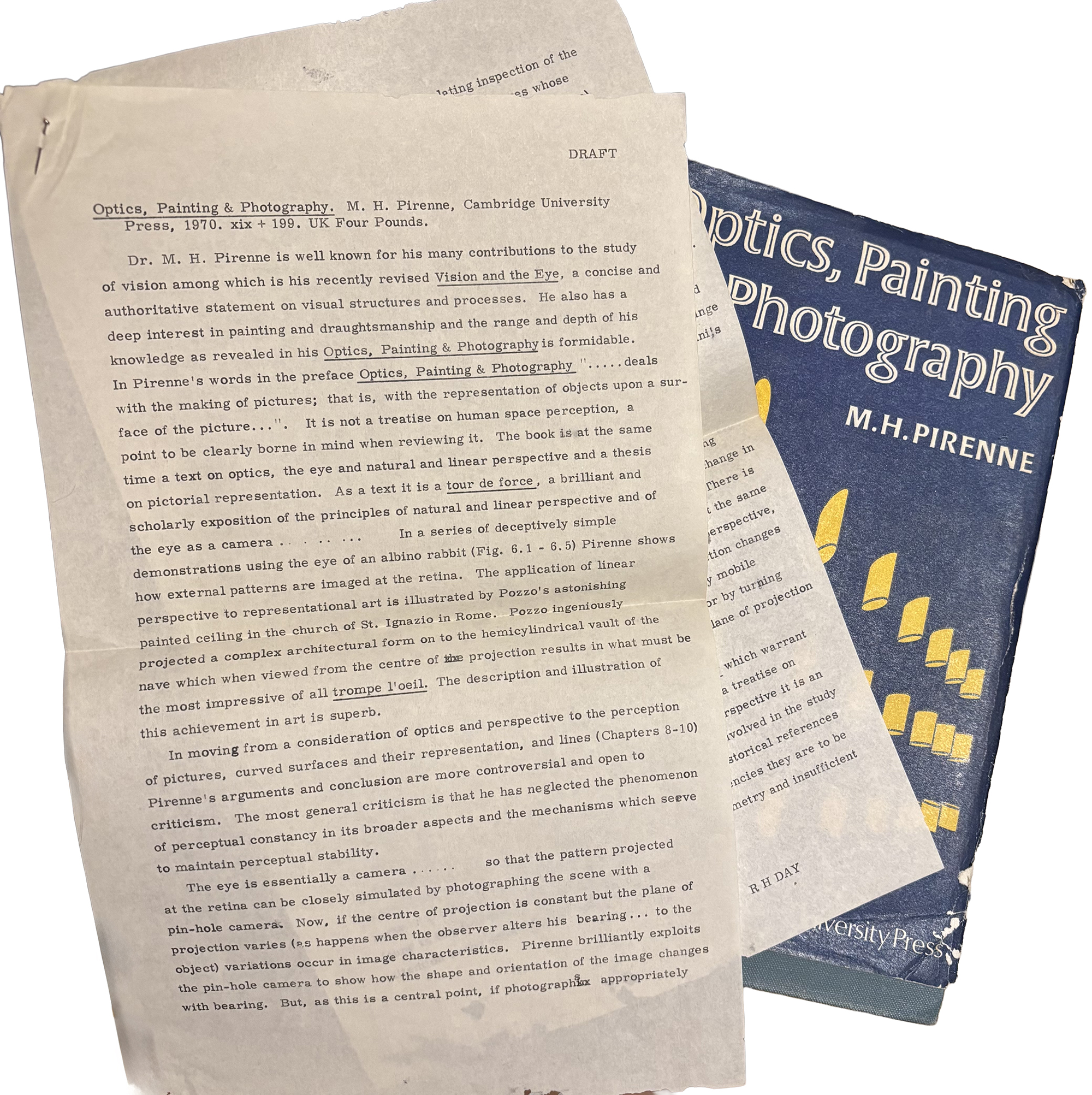

Reaching into his bookshelf he took out a volume and, giving it to me, suggested that I might be interested in the author’s use of the pinhole camera in exploring the illusion of perspective. Later, I found folded into the book typewritten copies of his review of it, the Belgian Maurice Henri Pirenne‘s Optics, Painting and Photography of 1970.

Indeed, Michael Polanyi in his foreword to Optics, Painting and Photography introduces the book as an exploration of how optical and physiological principles explain both our perception of the external world and the way we understand images. He frames Pirenne’s central problem: why certain perspectival paintings, like Andrea Pozzo’s ceiling in the Church of St Ignatius in Rome, display striking distortions when viewed from oblique angles, while most images seem stable from many viewpoints.

Pirenne’s finding is that the more perfect the perspectival illusion (as in Pozzo’s case), the more it collapses under skewed viewing, whereas most paintings remain recognisably coherent because the viewer never fully forgets that the canvas is flat—what Pirenne calls a “subsidiary awareness”:

Thus we may take it that, as we walk past a picture, we are facing a row of wildly distorted aspects of it and yet we unhesitatingly see these aspects as having the same undistorted appearance. Moreover, we see that Dr Pirenne’s explanation of this remarkable integration of incompatibles implies the joint operation of two such integrations, for it assumes that we see the whole array of distorted impressions in one single undistorted way because, along with the brush-strokes of the painting, we are subsidiarily aware also of its canvas. The mutual contradiction of the several distorted aspects may be said to be integrated to one and the same undistorted sight, each distorted aspect being integrated also to the awareness of the canvas which contradicts its perspectivic appearance.

Polanyi equates such ‘subsidiary awareness’ with Gestalt integration of parts into a whole by extending on Pirenne’s argument that viewing a painting involves an imaginative integration of conflicting sensory clues: distorted retinal images are reconciled with the awareness of flatness to produce a stable perception of the picture. This process resembles other sensory integrations studied in psychology, such as adapting to inverting spectacles, and demonstrates the active role of imagination in both the creation and appreciation of art. Polanyi concludes that Pirenne’s theory reveals an essential limit to imitation: if an image were to achieve complete trompe-l’oeil realism, it would fail across different angles of view, and its artistic force would be diminished. Thus, painting is necessarily an imaginative construction, not a literal reproduction of reality, and its distinct value lies precisely in this artificial, imaginative reality rather than in illusionistic deception.

Pirenne himself had inherited an interest in art from his father, the artist Maurice (Lucien Henri Joseph Marie) Pirenne along with a fascination with the convergence of visual physiology and artistic expression. While still at school he read of Brücke‘s experiments in anatomy, optics, and physiology, and Helmholtz on the optics of painting.

Day and I, researchers in different disciplines, psychology and photography, and on disparate rungs of academic status, had connected. Though we never met again (he died in 2018), I walked away feeling my exhibition strategy was vindicated. For the exhibition catalogue he promptly sent me his reaction to my photographic explorations of a novel rendering of perspective, and a summary of his own, allied, research:

The primary aim is to pursue the discovery that an impressively strong three-dimensional effect in a two-dimensional photographic representation of natural outdoor scenes occur when two cameras are aimed at a point in a scene and when a single camera is directed from one point of the scene to another thus blurring the space between them. These novel observations have potentially important implications for basic processes in three-dimensional (3D) vision and for the development of new ways for generating 3D effects in moving and stationary representations of scenes. We emphasize that the discovery is original and potentially important in both fundamental and applied terms.

My main research interests are in human and infrahuman sensory processes and perception from both empirical and theoretical standpoints. These interests derive in large part from my view that perception offers an entrée into the development and nature of human consciousness which I consider to be the central concern of contemporary psychology. My interests encompass perception in a variety of ‘applied’ situations, for example, in aircraft control, driving and in pedestrian locomotion; I have also worked on and published widely on perception in very early infancy and in individuals with intellectual disabilities. In recent years a good deal of my research time has been concerned with perceptual illusions. — Professor Ross Day: Adjunct Professor BSc Hons (West Aust.), PhD (Bristol), Hon D.Univ, Hon DSc, Hon FAPS, FASSA, FAA

I have written Wikipedia entries as a salute to these remarkable researchers, Day and Pirenne, and I was later to meet an associate of Day, Nicholas J. Wade whose A Natural History of Vision I had consulted for my PhD beside another friend of Day, Richard Gregory, who argues in Eye and Brain: The Psychology of Seeing for our acculturation of architectural space as influencing a false sense of perspective in such illusions as the Müller-Lyer, Poggendorff and Zöllner figures.

Day countered that the whole (gestalt) figure is the primary determinant of the illusion; “you don’t change the perception of illusions very much with experience; it hardly changes them at all.”

…from such contentions, further rumination is prompted. Visual perception and its illumination of the problem of attention and consciousness is very much a matter for photography.