What is the relevance of photography to the medium it spawned; cinema? Screenwriter Aviva Butt presents a challenge to practitioners of our medium in asserting that “cinematography is not photography.”

What is the relevance of photography to the medium it spawned; cinema? Screenwriter Aviva Butt presents a challenge to practitioners of our medium in asserting that “cinematography is not photography.”

Reviewing the early career and training of Prahran alumnus and cinematographer Gaetano “Nino” Martinetti, who has for 45 years been a highly regarded Director of Photography may help to reconcile that assertion.

During that time Martinetti has received four Australian Film Awards Nominations and several A.C.S Gold and Silver awards. His reputation grew within the industry as having a ‘painter’s eye’ and who achieved beautiful results quickly and cheaply.

In 1994 Nino won the A.F.I.(AACTA) “Best Cinematography”for the Paul Cox feature film Exile (1994). He has been the President of the Australian Cinematographers Society (State of Queensland) from 2004 to 2009 and in the State of Victoria from 1992 to 1993. Nino mentors film students at Griffith University, Bond University and New York Film Academy (Australia). In 2019 Nino Martinetti ACS was inducted in the Hall of Fame of the Australian Cinematographers Society. He remains passionate about cinematography.

Martinetti was born in Rome on 15 January 1946. There he studied Humanities, Sciences and Art at the College Santa Maria and at the Institute Manieri-Copernico Liceo Scientifico. Soon after that, he was conscripted into the Army.

In 1970 he moved from Rome to London to study English and there he developed his interest in photography. Seeking to advance his knowledge and passion of the arts and film-making, with his former wife he travelled overland from London over several months, arriving in Darwin NT in November 1973:

“I have been asked many times during interviews or by my ex-students how I became a photographer. It was in 1973, when I was in Bali on my way to Australia. I ate a mushroom omelette.”

“I was twenty-nine years old, and thought I knew very little about photography, but it had become a passion. I also didn’t know much about Australia and didn’t know many people here. At that age, I thought coming here was a big and risky investment in my future.

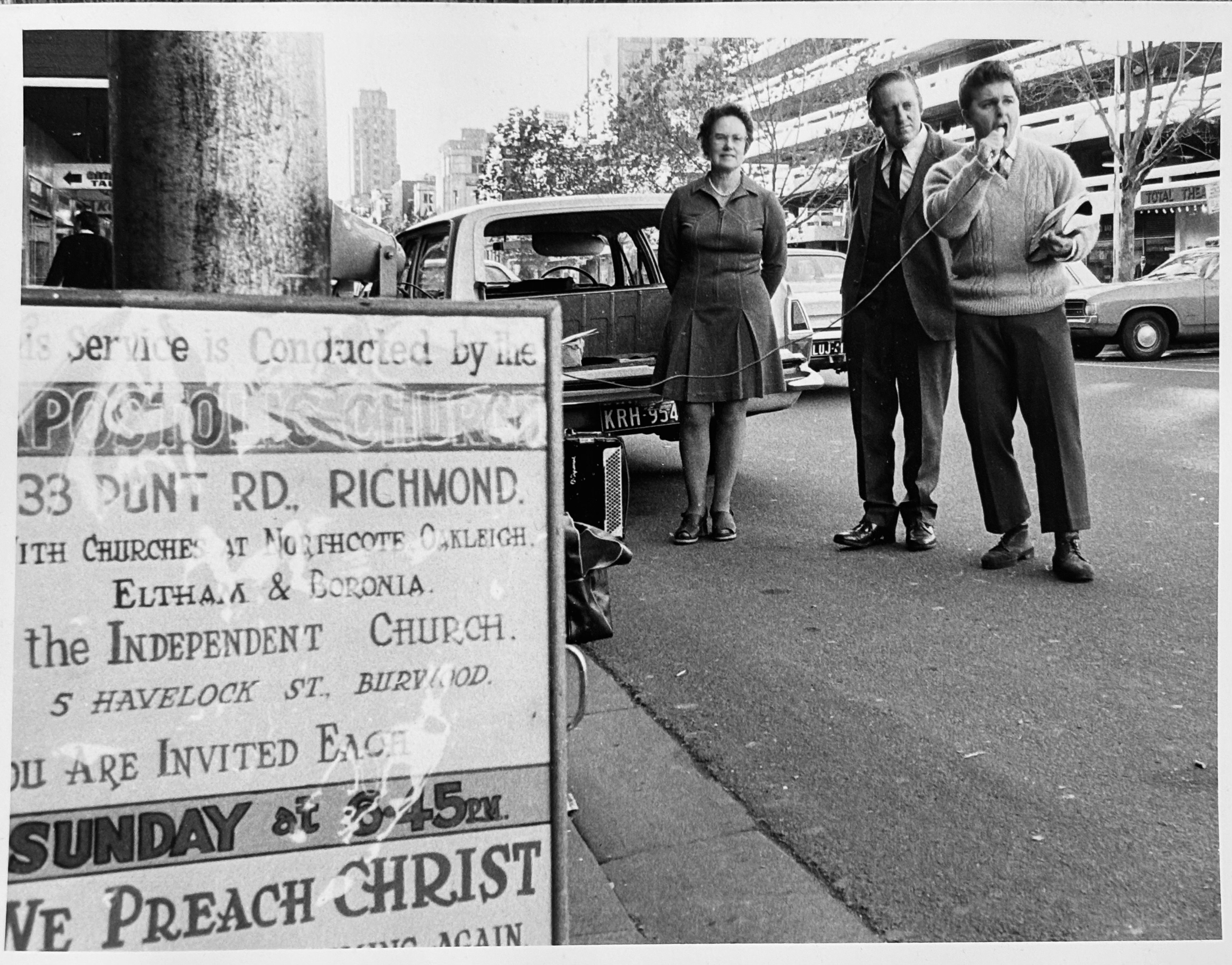

“Luckily, Tony Trengove, an Australian [interior designer] from Sydney whom I had met in London, gave me the address of his grandmother, Isa Johnstone, in Drummond Street, Carlton. She was an artist, an amazing and classy old Australian lady. Unbeknown to me, not only I was right in the hub of the art and cultural scene of Melbourne but also in an Italian suburb. Isa took me to Toto’s Pizza in Lygon Street and got me a job there as a waiter. We went to see a performance at La Mama theatre and, as an Italian, I couldn’t believe how small the theatre was. Mrs Johnstone really was the person who launched my future in Australia and I am very grateful. The early years of the seventies were the beginning of a new political and social era in Australia; the government was investing in the arts and free education and it was my good fortune to be here.

“While working at Toto’s, I met Jaems Grant who was a regular customer and a student at Prahran College of Advanced Education. We became friends and talked about our common interest in photography and alternative lifestyle.”

“Jaems kindly organised a meeting with Athol Shmith and thanks to him I was admitted in 1975 to start my Diploma of Art & Design, majoring in Photography, Film & Video. I left during the second year in 1976. Studying during the day, I was working night shift at the restaurant so saved enough money to buy a Nikon F2 with 3 lenses: 35 mm, 50mm, 135mm and a Lunasix light meter.”

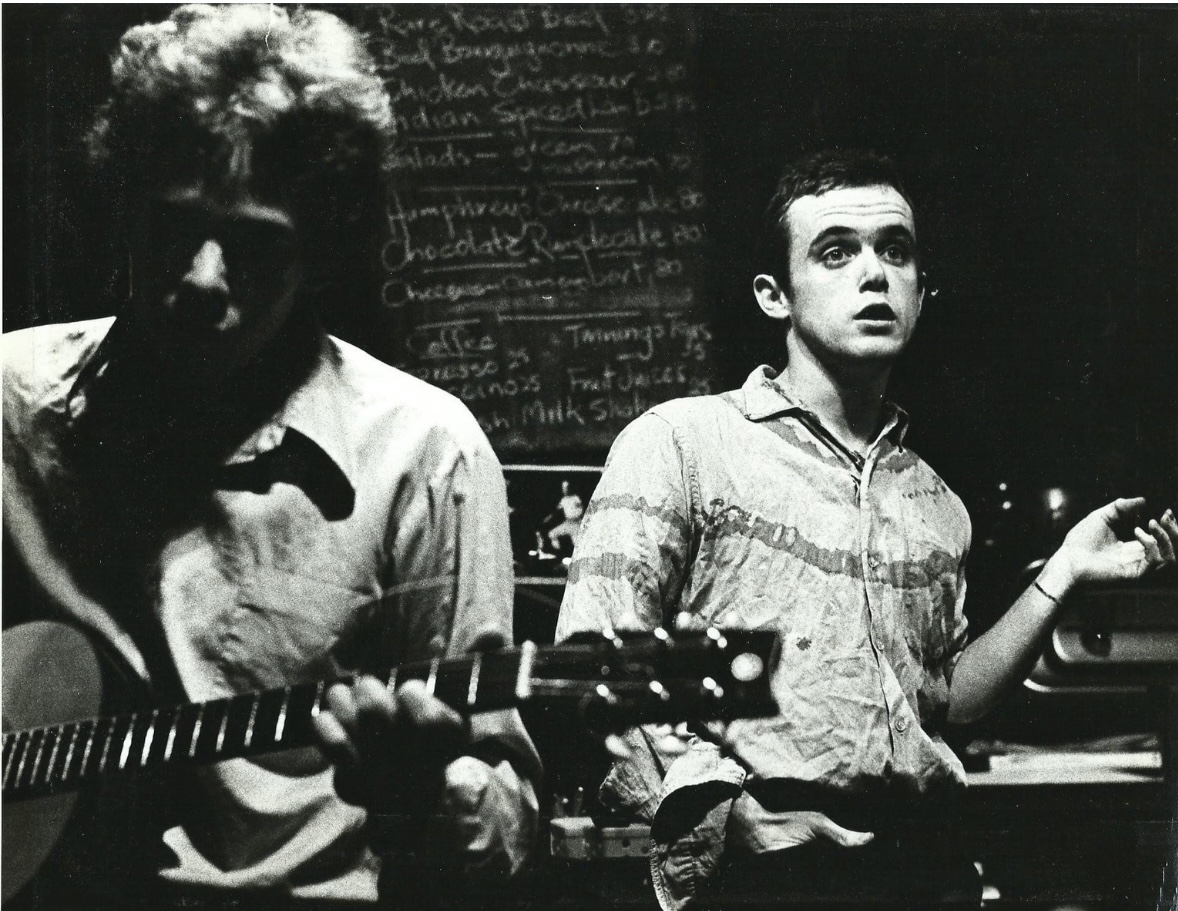

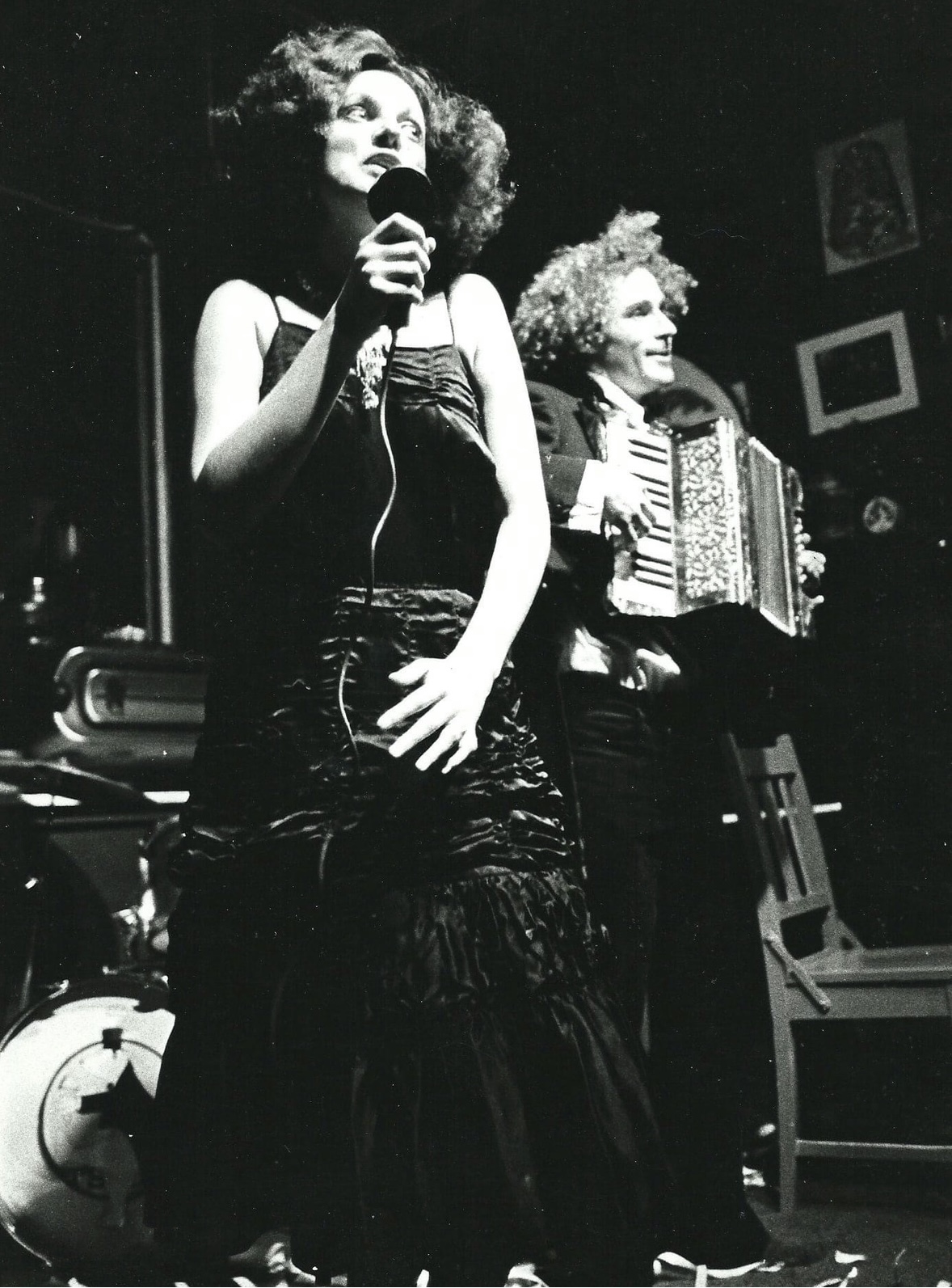

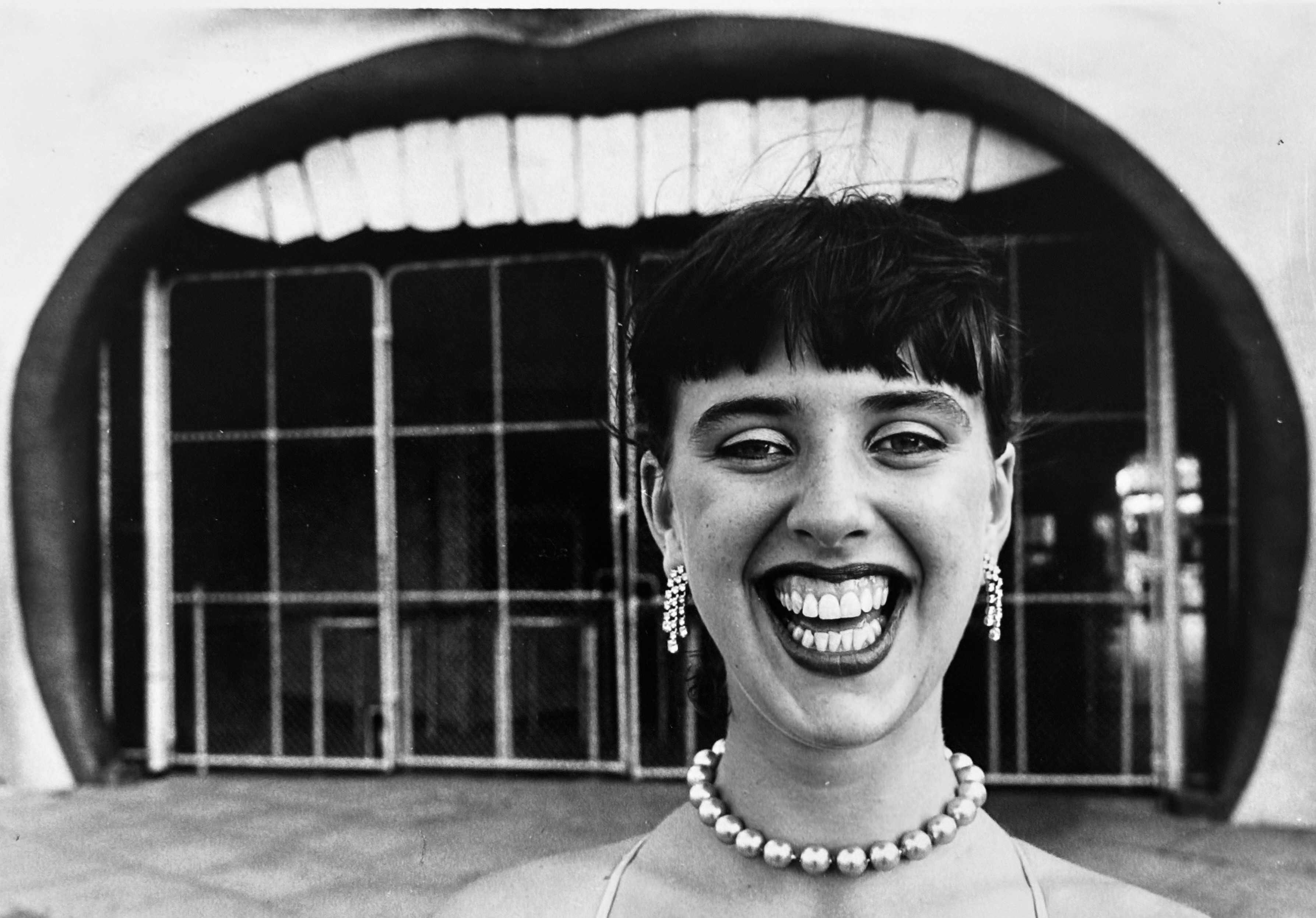

“Soon after, I met another pivotal figure in my career, John Pinder, the owner of the Flying Trapeze in Brunswick Street, Fitzroy (find attached his letter of reference) and became a regular at his Theatre Restaurant, I started taking pictures of the shows and meeting the many different, talented, friendly artists who performed there.

“One good thing led to a better thing; John Pinder introduced me to Ponch Hawkes a photographer, a legend, who is also part of my journey and to whom I am very grateful; I cannot find enough words to describe how kind and generous she was by letting me use her darkroom.”

“Shooting at night inside the Flying Trapeze with available low light was very challenging for an inexperinced photographer. The very small stage didn’t help either. I was shooting with fast lenses at f1.4 with no depth of field and low shutter speeds hand-held; I had to keep the camera very steady. Working with available light I developed my own style of exposure and composition. Later on, as a cinematographer, available light became one of my strengths.”

Of his work on Paul Cox’s Golden Braid, Donald McDonald notes that:

“There is scarcely a handful of full light exteriors in the whole piece. But Nino Martinetti’s elegant cinematography makes every beam of light into a useful statement to reflect and advance the progress of the drama.”

The Canberra Times, 20 March 1991

“I never had the time to look back, but now fifty years later and reflecting on my humble beginnings as a student photographer, I see it as an invaluable experience and I am still very proud of my early work. Prahran CAE and my teachers and mentors like John Cato, Paul Cox and Athol Shmith left an indelible mark in my heart and on my craft.”

“As a student, I was inspired by photographers such as Henri Cartier-Bresson, André Kertész and Dorothea Lange, and like them I have always composed in the camera viewfinder and printed full frame mainly 10” X 8”, or 6 ½” X 4 ½”, and never cropped, which is an excellent discipline for cinematography.”

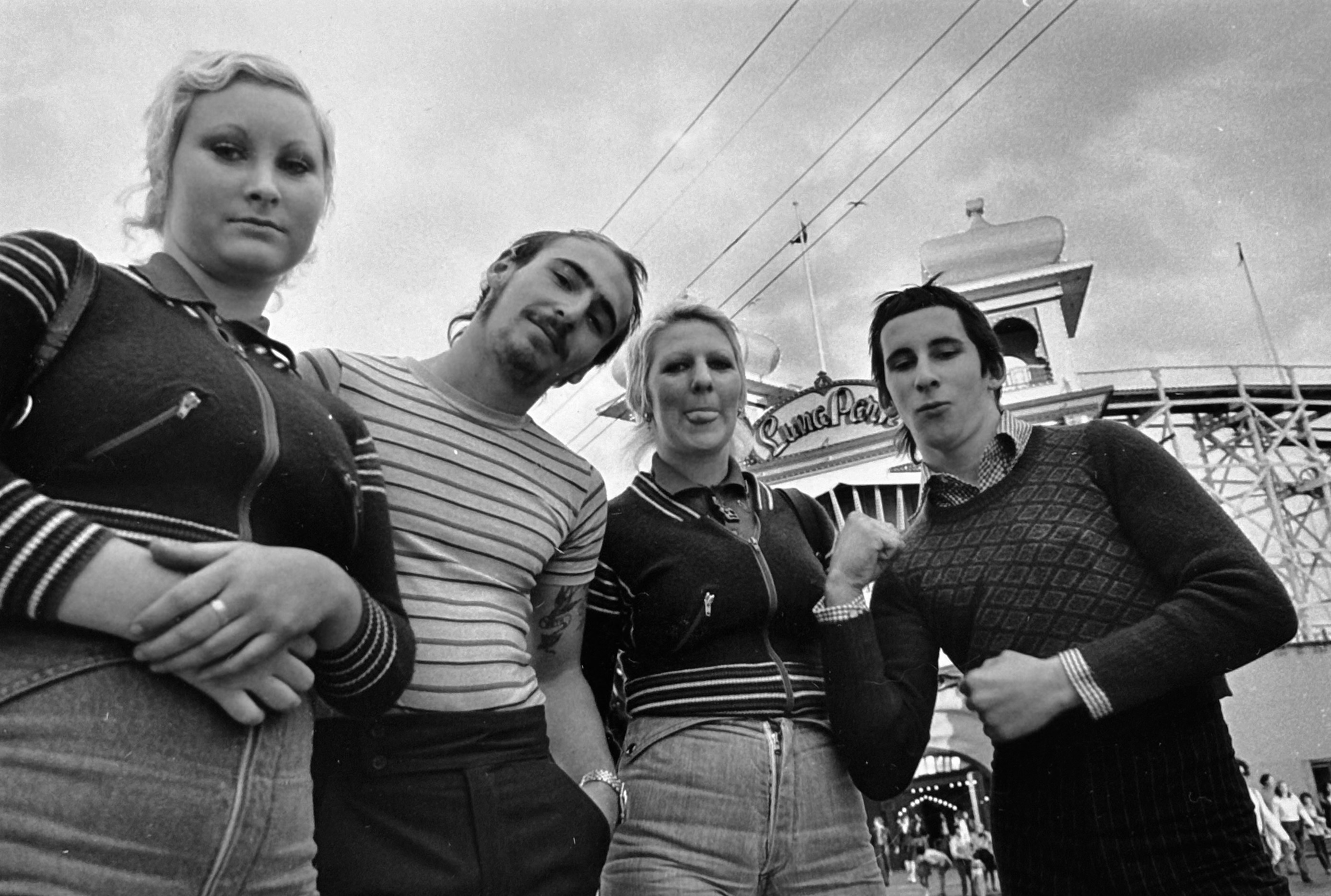

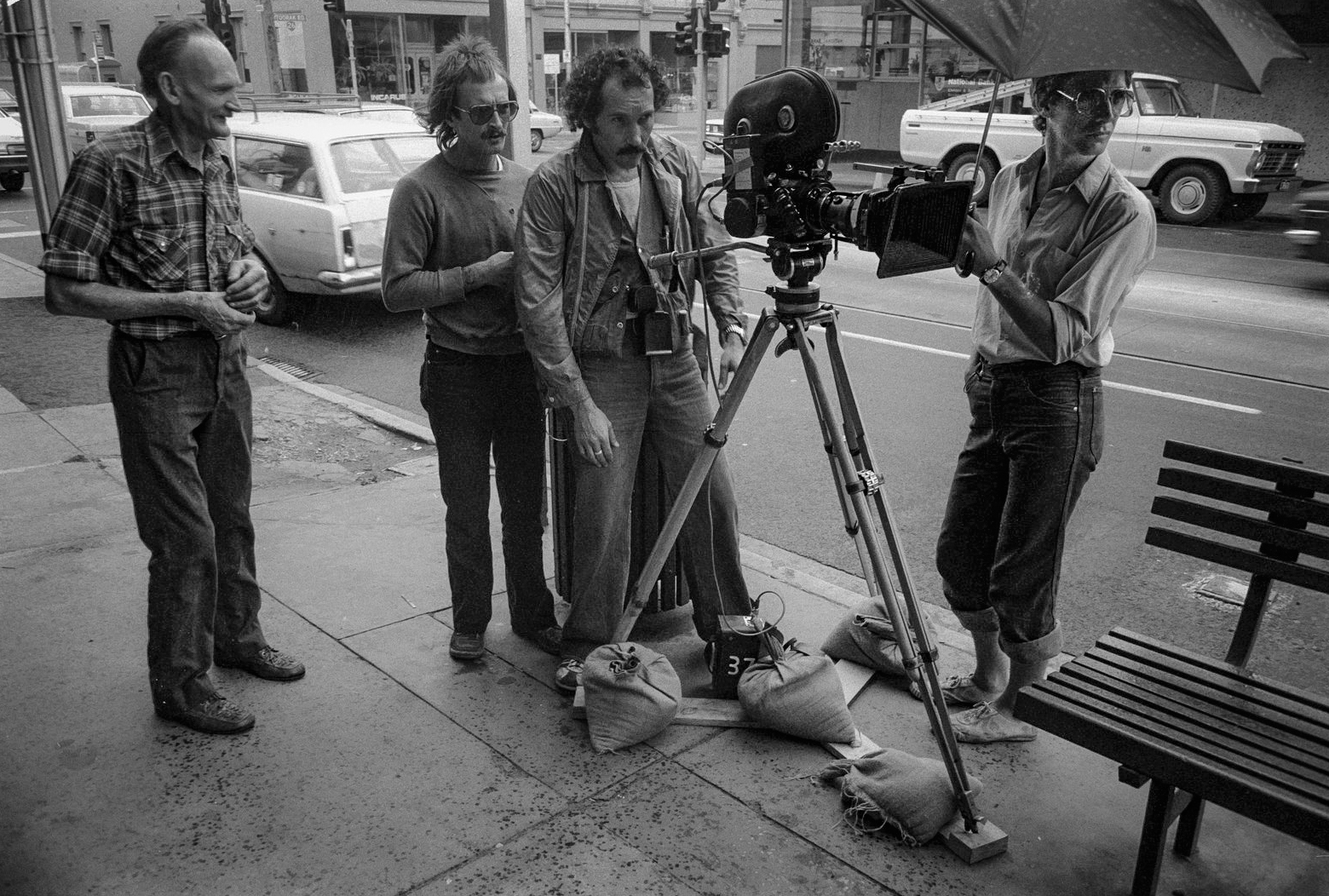

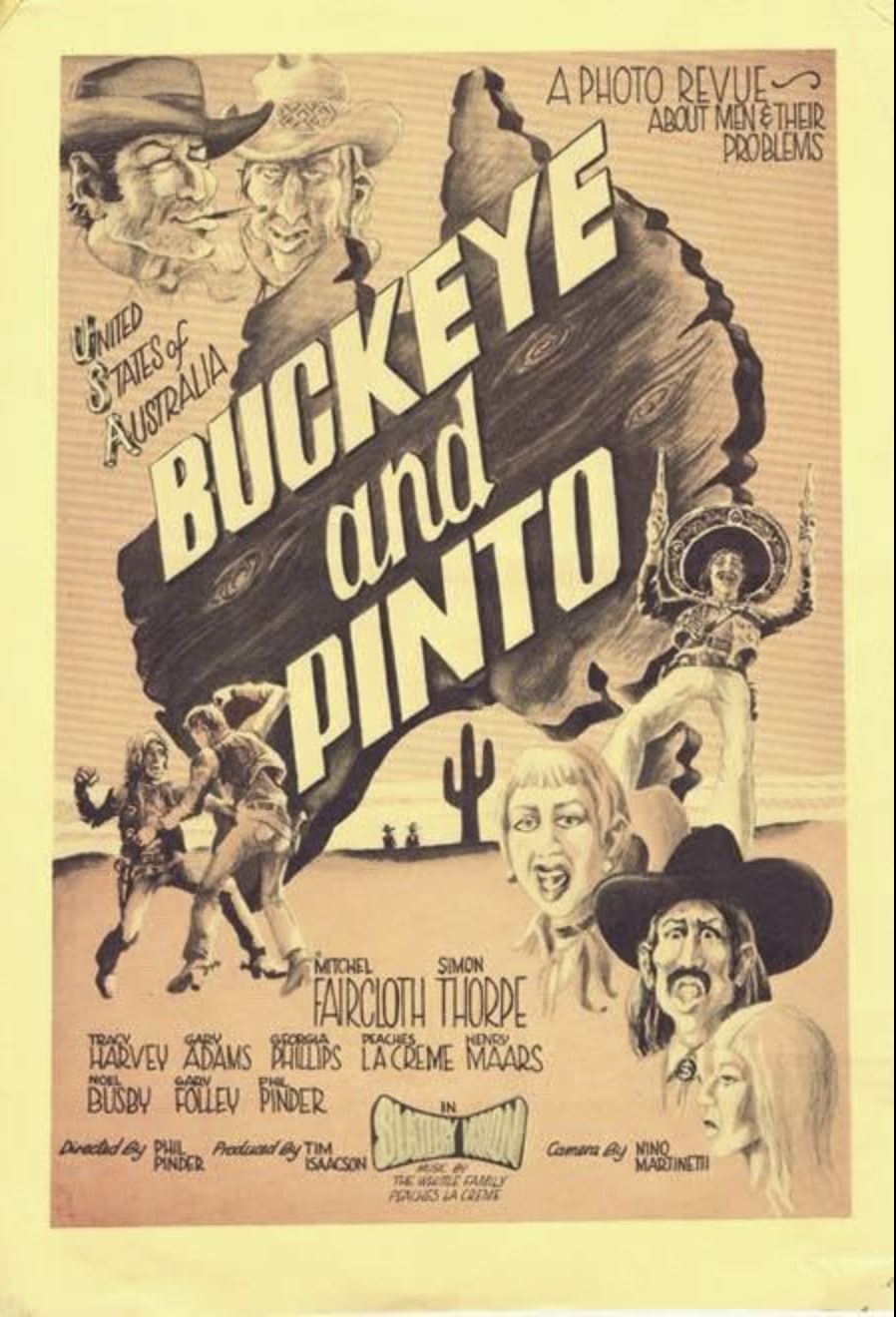

“With Phil Pinder (John’s cousin), David Shepherd, Mitchell Faircloth and Tim Isaacson we became a team with the talented Isacson as producer, and went on to make two no-budget films; Buckeye and Pinto, my first, which parodies traditional westerns with a homosexual subtext; two cowpokes ride the range in the good ole USA (United States of Australia) shooting everything that moves. Starring Mitchell Faircloth, Simon Thorpe, Gary Adams, Gary Foley, Tracy Harvey, Peaches La Creme, Henry Maas and Phil Pinder, it was nominated for AACTA Best Cinematography—my first!

“Straight after we made Terror Lostralis which was nominated for AACTA Best Direction. These were the only no-budget student films that were release in a cinema (Valhalla) which returned some money and became cult movies.”

“After these two unforgettable experiences, I started my career a Cinematographer, which is another story and not an easy feat.”

It is illuminating from a photographic point of view to read Nino’s introduction in screenwriter Aviva Butt’s book On Screenwriting and Love and Politics,1 in which she writes that

“cinematography is not photography. Rather, photography is but one craft, which the cinematographer uses in addition to other physical, organisational, managerial, interpretive, and image manipulating techniques to affect one coherent process”.

Nino highlights the collaborative nature of filmmaking and the significant role that screenwriters play in shaping a film’s visual narrative. he emphasizes that while the screenplay provides a structural foundation for a film, it is not the final word but the raw material that directors and cinematographers interpret and expand upon during production. Martinetti notes how Butt’s screenplay Blue Mist, the subject of the book, transcends mere entertainment, incorporating poetic elements and addressing complex themes such as the Palestinian-Israeli conflict. Butt’s awareness of the capabilities of cinematography is noted, particularly regarding how visual effects can enhance the narrative by blurring the lines between reality and fantasy, especially given the experimental nature of Butt’s screenplay, which employs a three-fold point-of-view, requiring interpretation by cinematography.

The cinematographer, he says, acts as a translator of the screenplay, converting its written words into visual language. This process he likens to translating from one language to another:

“if you were to give the same screenplay to five different cinematographers, it is most likely that they would all come up with a different visual interpretation-relative to the cinematographer’s own nationality, cultural background and location of the shoot. As with any mode of expression, the cinematographer’s familiarity with the idiom and etymology of the vocabulary of the mother tongue affects the translation into the visual language.”

Light, Nino writes, is crucial for visual storytelling and experimentation:

…the cinematographer must understand the connection of our inner light or divine light with the physics of the visible spectrum and the branch of optics, since each frame deals with the nature of light. The spectacle may thus be regarded as experimentation in sound, color and rhythm, and from the perspective of the cinematographer, an artistic and innovative use of light.”

Nino worked on several films by his former lecturer Paul Cox: Kostas (1979) as assistant camera operator; on Lonely Hearts (1981) as focus puller; camera operator on Man of Flowers (1983), My First Wife (1984) and Cactus (1988); provided extra photography for Vincent (1987); was Director of Photography on The Gift (1988) and Golden Braid (1990); he acted the part of the cafe manager in A Woman’s Tale (1991) and was the camera operator for both that film and The Nun and the Bandit (1992); then was D.o.P. on the award-winning Exile (1994) and Molokai: The Story of ‘Father Damien’ (1999).

“In 1977 I became an Australian citizen and still very proud of it.

“As they say, you never forget your first love, I am still enjoy photography, taking beautiful pictures with my iPhone 15. I shot thousands of photos B&W and colour but unfortunately now, due to my bad filing habits and travelling, I only have some bits and pieces left and not necessarily the best examples of my work.”

Footnotes

- Butt, Aviva, and Dunedin City of Literature Collection. 2013. On Screenwriting and Love and Politics : The Screenplay Blue Mist. Houston, TX: Strategic Book Publishing and Rights Co. ↩︎