The postmodern position on documentary photography challenges the traditional notion of photographic truth and objectivity, recognising that documentary images are not neutral representations of reality; they are constructed narratives shaped by the photographer’s perspective, intentions, and cultural context.

The postmodern position on documentary photography challenges the traditional notion of photographic truth and objectivity, recognising that documentary images are not neutral representations of reality; they are constructed narratives shaped by the photographer’s perspective, intentions, and cultural context.

Documentary photographers in the postmodern era understand that some level of manipulation or dramatisation is often necessary to convey meaning and create compelling accounts, even as they strive to represent real events or conditions. Strategies are applied to staging, appropriation, or digital manipulation evade or challenge viewers’ assumptions, so that the constructed nature of photographic representation is left open to multiple interpretations, not as an objective record, but to present an insight, a prompt or provocation.12

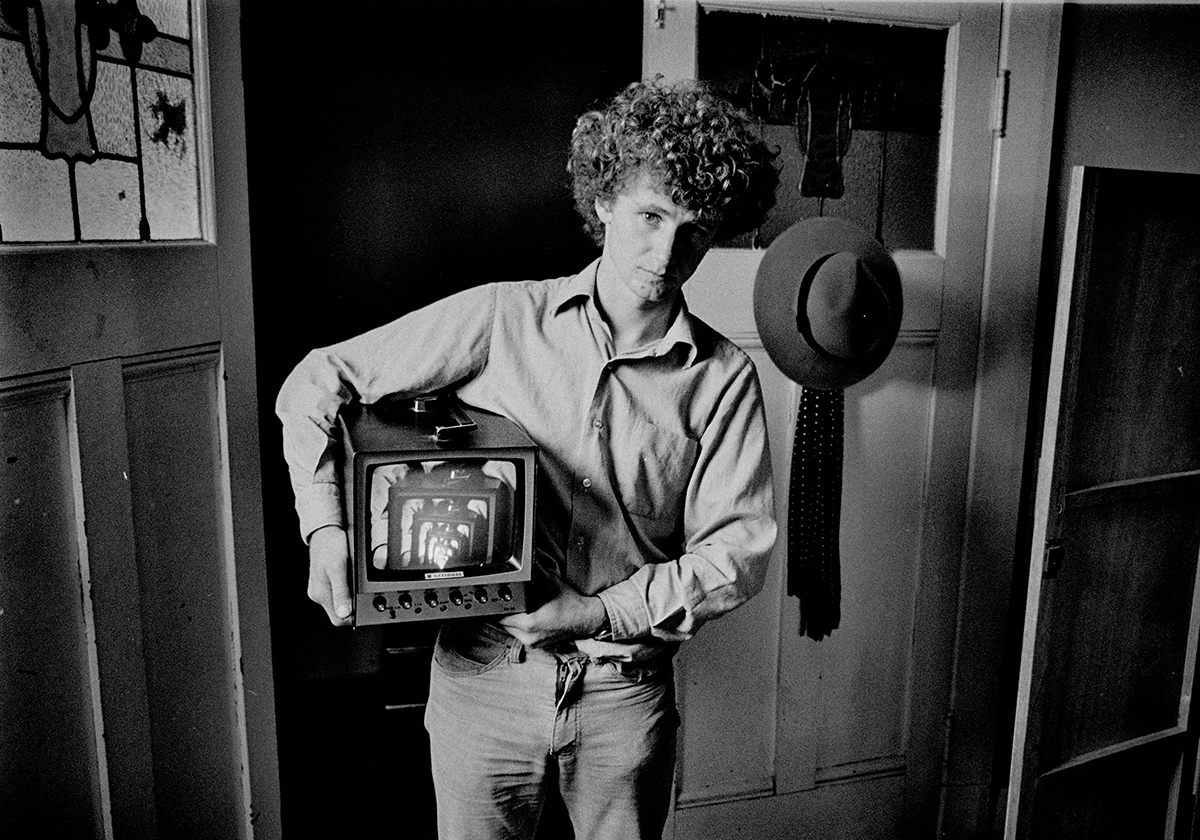

Ian Tippett was born in regional Victoria’s Ballarat in 1958. Though there were no artists or photographers in his family they enjoyed seeing European cinema at the city’s Film Society. Teaching himself the basics of photography gave Ian the ambition and means to leave school, and provincial Ballarat:

“I landed a job in the Latrobe Studios black and white lab in South Melbourne. I was reading Creative Camera magazine at the time, then found Prahran College photography through the Australian Centre for Photography publications.

“In 1977, after introducing myself at Prahran, I was advised to do their preliminary year, which was based on Bauhaus methods and enabled me to generate an entrance folio for the photography department.”

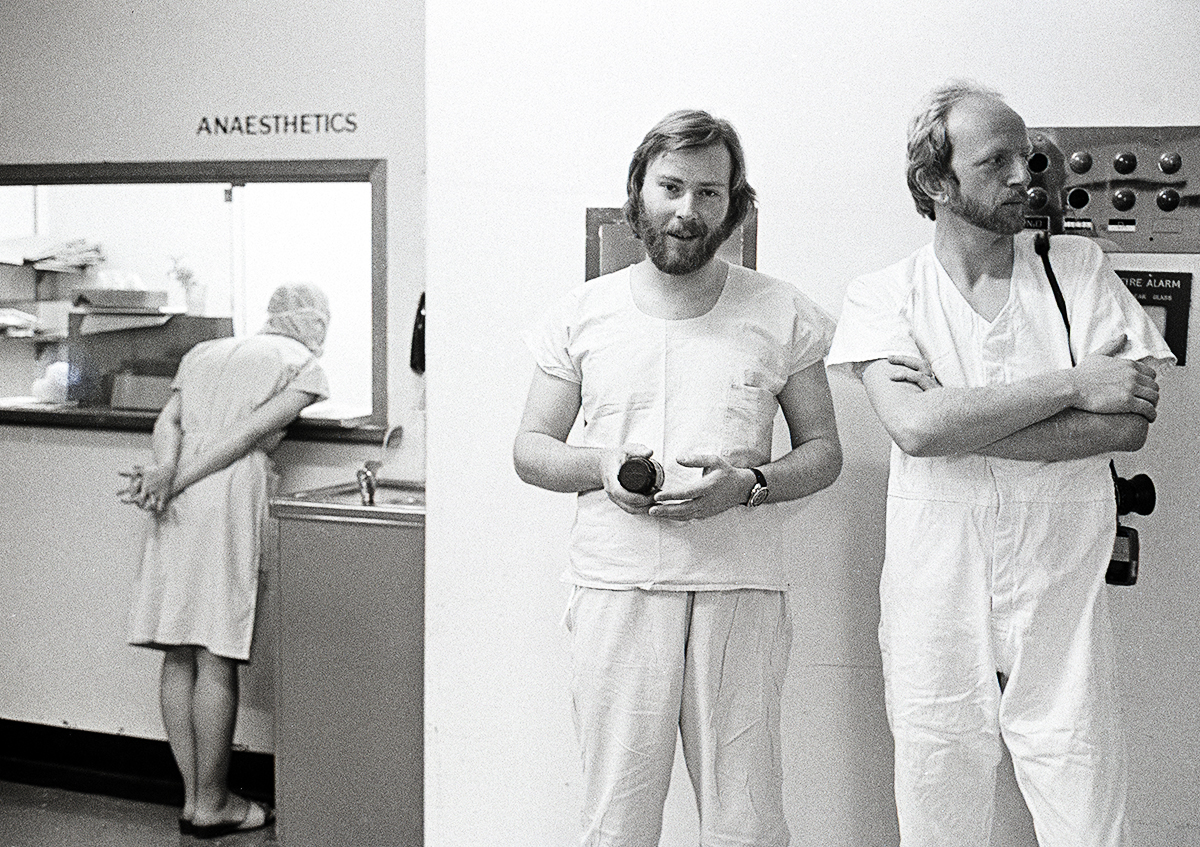

“1978 was first year, we learnt to take lots of photographs, we bulk loaded TRI-X and soaked it up. I remember the documentary assignments ranging from Moomba to a day on public transport and Royal Melbourne Hospital, where we had full access.”

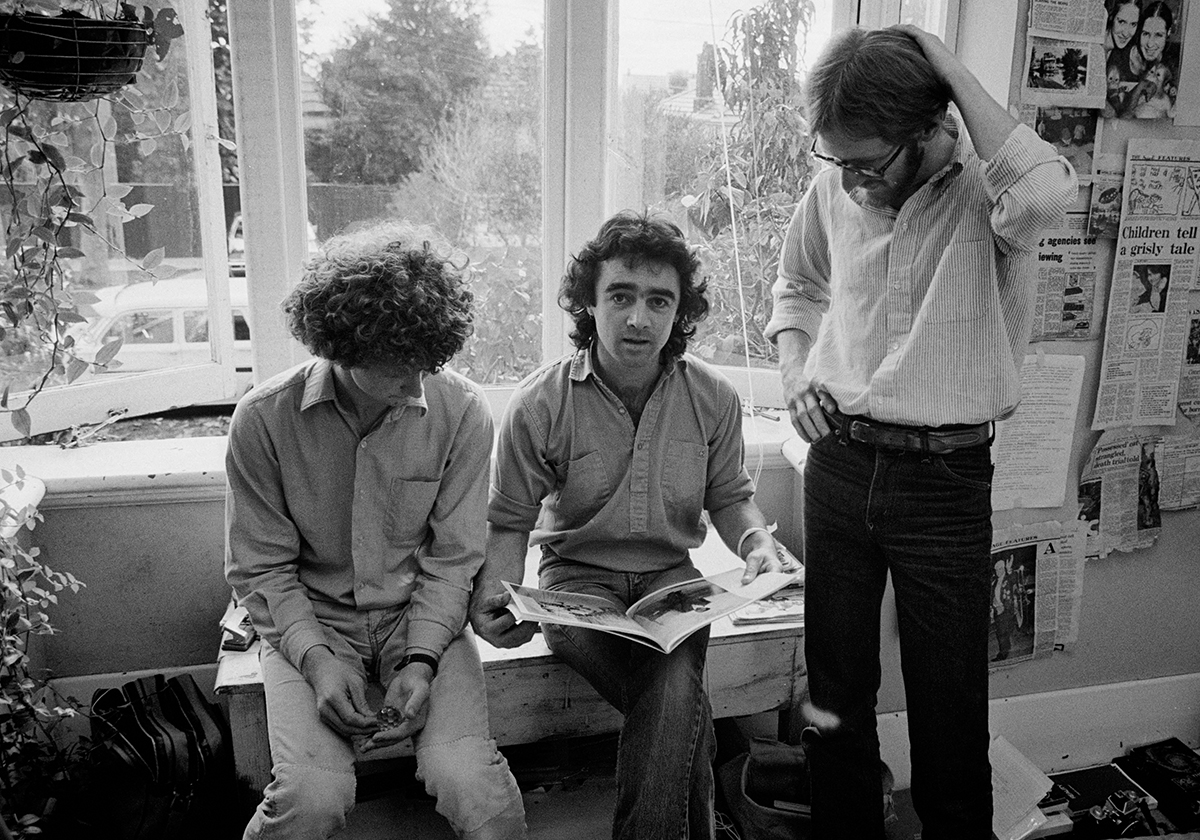

“We had strong art history lectures that gave good context for our photography. There was a focus on the surrealist qualities within straight photography as opposed to manipulated or romantic styles. The artists we admired, such as Walker Evans, Robert Frank and Diane Arbus often had political or outsider perspectives.

“My memories of the first year include positive collaborations where students helped each other without intimidation or competition. The course had little technical instruction, which made sharing knowledge within the group important. We learned to trust our own judgments over the vague assessment of assignments and portfolios.”

“In 1978, Prahran photography seemed like a relic, relegated to the basement, a large darkroom, isolated, secretive, and forgotten. The photography was rooted in technical modernism, following the Ansel Adams aesthetic and darkroom discipline.”

“This fine art approach was countered by a style of black and white documentary photography seen in Life magazine of the 1960s. We were part of a shift influenced by punk and Post Modernism, we challenged the heroics of documentary photography and followed the shift to the colour and nostalgia of Post Modernism.”

“In this period at Prahran we were given the tools for looking at photography, we learned to create conceptual models and intuitive pathways that would always stay with me.”

After Prahran Ian exhibited in a group show Matters of Personal Choice in 1984 at The Australian Centre for Photography in Sydney. Throughout his career Ian has intermittently stopped practicing in the medium and of this hiatus says:

“My return to photography was after a long time and even now I can go for long periods without taking photographs but I was always interested in what was happening. I remember seeing Bill Henson at Realities Gallery and Pinacotheca Gallery in 1986. The use of large format colour prints in galleries became a movement from this time where photography was seen in different places.”

In the interim Ian found employment in different roles not involved with photography before returning to study over 1996–98, taking a Bachelor of Design at Swinburne University. After graduating and five years of undertaking freelance commissions, he showed Day to Day in the group show Time-Movement-Space at Linden Centre for Contemporary Arts in St Kilda 29 October–23 November 2003 with Linda Van Kalleveen, Marisa Keller, Saffron Newey, Niomi Sands and Anthea Boesenberg, after which, and into the mid-teens of this century he has been showing regularly.

His Ground Level., shown in 2005 at both Conical Inc., 3 Rochester Street, Fitzroy3 and Rocketart4 galleries attracted attention: reviewer Jill Stark in The Age 25 April noted its unique perspective in capturing Melbourne streetscapes from the pavement level in eight images that truncate the lower limbs of passers-by—’the businessman’s polished shoes waiting obediently by the kerb…the raw sexuality of a young woman’s bare calves radiantly bathed in sunshine’—and present them within a darkened domain of ominous ‘territorial-looking’ pigeons. Ian is quoted on his desire…

“… to create some sort of tension…a cinematic atmosphere reminiscent of a Hitchcock film. The main thing is a tension that’s beyond the usual way of looking at things. Street photography is a…subterfuge. The camera wasn’t hidden: people just didn’t bother about it.”

Robert Cook’s review ‘Come Stay Away (This is not a love song)’ in the Australian Centre for Photography periodical Photofile (September, 2005) extends a further comparison with cinema to decipher Tippett’s Ground Level imagery. Manhattan’s hyper-urbanity in the cliché vignettes running under the opening credits of Herbert Ross’s 1987 The Secret of My Success introduce Cook’s emphasis on the complex and often disillusioning relationship between individuals and urban environments. He contrasts the vibrant, transformative nature of American cities with the more sterile administrative centres that he asserts are the Australian conurbations. To this end he enlists Tippett’s photography of Melbourne capturing the more sombre and alienating aspects of Australian urban life for comparison with the vibrant, transforming experience associated, in popular culture, with American cities.

Cook describes Tippett’s work as being “ruled by shadows,” in alignment with his stance that Australian cities lack the dazzling catalytic energy of their American counterparts. This imagery of shadows suggests a sense of emptiness and unfulfilled potential in Australian urban spaces. Where Tippett’s photographs depict people negotiating urban spaces or more specifically “standing around like dumbfucks” like “extras in a noir meets Beat Strueli deal” they portray a sense of disconnection and aimlessness; Australian cities, Cook says, fail to foster genuine community or creativity and lack the dynamic interplay between individual aspirations and urban transformation that he associates with American cities portrayed in popular culture by figures like Michael J. Fox.

Cook, writing in hitsong-lyric catchphrases, stresses the lack of authenticity and engagement in our urban environments where Tippett’s work, he says, captures the reality that “capital and the city may have merged but without an ethics and a subjectivity and a heroics.” For Tippett that statement:

… sums up the trap by which photographers are diminished by arguments over ethics. I learnt early that idea of the heroic photographer was a falsehood and the pursuit of the ‘hero image’ was not interesting to me.”

Tippett in email to James McArdle

From 5 Apr – 15 Apr 2006 Tippett next exhibited Black Day, solo, at Seventh Gallery, 155 Gertrude Street Fitzroy (now at 213-215 Church Street, Richmond) for which Rosalind Middleton wrote the catalogue essay. She describes how Tippett takes advantage of the effects of a rainy, gloomy day on both the Melbourne cityscape and its inhabitants through his elevated camera angle and selective flash. His technique, she notes, imposes a cinematic atmosphere overlain with the tension of urban surveillance and the scrutiny of security cameras. Meanwhile his hooded and cloaked subjects, armoured against the elements, retreat into an introspective solitude, isolated from bustling surroundings. Self-awareness and withdrawal are embodied in the defensive postures people adopt in public spaces, a psychology made visible by their sheltering from inclement weather:

“Tippett is working within a form of documentary photography which invests the works with the possibility of narrative and insinuation without relinquishing the power of fact. Black Day becomes not only a record but also a construction of the rainy city.”

Middleton concludes that Tippett transforms the city into a theatre of the darker aspects of urban life that resonates with viewers by articulating shared fears and the instinct to armour oneself against the complexities of contemporary existence.

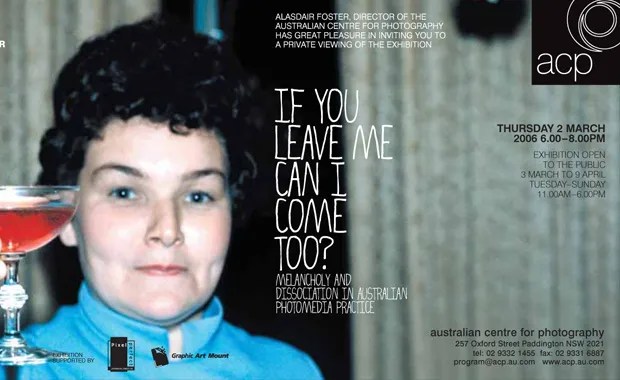

Shortly after, over 3 March – 9 April 2006, Tippett participated in a group show If you leave me, can I come too? (taking its title from the deadpan irony of a Mental as Anything break-up song) at the Australian Centre for Photography. Other works shown included Lyndal Walker’s series Stay Young, of young men in their unkempt flophouses, Greta Anderson’s Walking and Talking and Boris + Natascha’s video parodies of New Age self-help tapes. Tippett showed in the series The Last Cigarette the isolation and stubborn determination of smokers banished from their workplace to indulge their addiction in discomfort.5

Appropriate to his marooned subjects, Tippett’s The Last Cigarette series was mounted in the ACP foyer opposite Natasha Johns-Messenger’s Lost in Space. Mireille Juchau in a piece titled ‘Melancholies various’ notes that the series continues, from Ground Level, Tippett’s “interest in the rituals and details of the CBD”:

“Tippett frames his human subjects amid the monumental geometries of city buildings, savouring a drag in a high-rise foyer or reflected in windows on concrete forecourts. The smokers stand mostly alone, modern pariahs, their faces wreathed in toxic plumes. One woman has closed her eyes as she draws back—she might be in pleasure or pain— but these are rare moments of personal time stolen from corporate routines.”

However documentary photographer Robert McFarlane in his review of the show in the Sydney Morning Herald, while praising Tippett’s acute social observation and ‘strong compositions,’ makes unnecessary comparison with Trent Parke, thus seeming to miss Tippett’s use of the architectural settings—we don’t need to see a whole skyscraper to understand their “inhuman scale”.6

His series Magnolia appeared at the Queensland Centre for Photography 25 Aug – 16 Sep 2007, titled for the magnolia as a beautiful garden plant that was slightly diminished by suburbia. Images of the flowers accompanied the street photography.

Ray Cook in the QCP publication catalogue observes that:

“Every large city is comprised of two types of vistas, those that make tourist brochures and those that do not. Ian Tippett photographs Melbourne; its vast banal suburban spaces, its oblivious inhabitants often shot from the car window as he passes them. Dwarfed by suburban universalities, figures in his pictures negotiate the spaces and serve as anchors, reminding us of the fragility of human subjectivity. Economic rhetoric and a dearth of embellishment call to mind a pertinent quote from Gary Winogrand, “there is nothing as mysterious as a fact clearly described.”

Tippett’s entries were shown in Queensland’s $25,000 Josephine Ulrick & Win Schubert Photography Award, Australia’s richest, in both 2007 and 2008, and also in 2008 the State Library of Queensland exhibited his work in Memoirs, Selected Photographs from the Daryl Hewson Collection an archive that is considered to be the most comprehensive archive of photographic art in Queensland, and which contains three of Tippett’s photographs.

In 2009 Ian showed Lightness at the Queensland Centre for Photography of which fellow alumni Peter Milne wrote in the catalogue:

“Ian Tippett advances us a little more along our spectrum. He is clearly responding to the venerable tradition of street photography and yet we are again presented with work that compels us to question the conventions it draws upon. His street photographs do not read as candid moments ‘captured’ from the spontaneous dynamics of urban life. The subjects are pointedly ignoring the camera (and by extension ignoring us). The individuals depicted are actually participating in a visual dialogue through their conscious resistance to it.”

During 5 – 27 June 2009 at Kings ARI, Melbourne Tippett joined David van Royen and Vivian Cooper Smith in We Were Young which the artists developed collaboratively in conversation, agreeing to hang three large-scale prints each, insinuating undercurrents of fear and anxiety through a juxtaposition of ordinary and imaginary, and the calm and the anxious. Tippett’s young people block the world with music from their iPod earphones, escaping into musical fantasia.

At the C3 Contemporary Art Space at the Abbottsford Convent in Melbourne Tippett was represented in the 2010 group show Golden Mountain, then after a brief hiatus showed Still Motion there in December 2012. The HD video animation projects a photographed male figure into a simulated pool of water, recalling Narcissus captivated by his reflection, frozen in the still image but given breath through the liquid motion.

Over 3 April – 8 June 2014 Monash Gallery of Art, now the Museum of Australian Photography, presented in New Photography From The Footpath the work of Melbourne based artists Glenn Sloggett and Catherine Bell with Ian Tippett to represent diverse approaches to the ubiquitous genre of street photography.

For the work acquired for the MAPh collection Tippett provides this insight:

“This street portrait is only a fleeting view where a moment in time relates to transitory ideas of self. Transition to a vivid hair colour is a semi-permanent transformation with a passing allusion to nature. The photograph holds time, but the subject slips away with the shifting of identity.”

Artist’s statement, Museum of Australian Photography

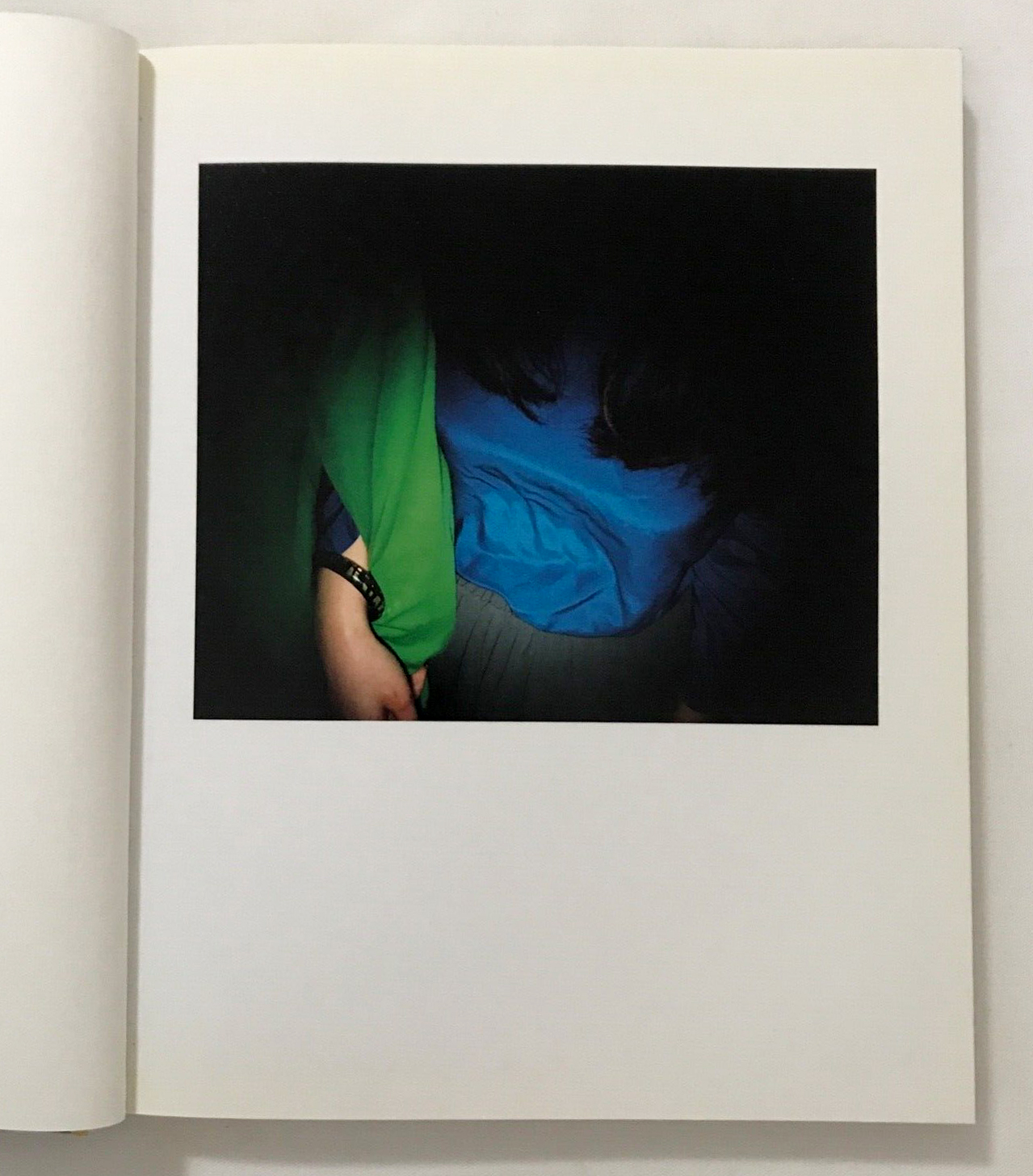

That same year Ian self-published the book I Want You Back which continues his twist on street photography, a disorienting tilt in fact and a confusing merging of media.

For this series Tippett’s photographs at an intimate distance with his camera angled down onto the bodies of young people; as if we are behind their own eyes, no faces are seen. Dressed in t-shirts or other illustrated costumes, their torsos or backs bear banner-like icons of popular culture that undulate over their anatomy and are distorted by steep perspective. The shift between intimacy and distance is purposely unresolved as the private occupies public space. Expressions of individuality join the collective realm of images.

Photo Independent art fair which ran 1–3 May 2015 in Los Angeles dedicated a section, called Photobook Independent, to photographers who work and exhibit in the book format. As Victoria Cooper and Doug Spowart record on their blog, the QCP curated a selection of 16 Australian photo publishers to present in the L.A. event. The photobooks included Tippett’s I Want You Back and publications by Ingvar Kenne, Dane Beesley, Anne Ferran, Lindsay Varvari, Rohan Hutchinson, Julie Shiels, Prudence Murphy, Christopher Young, Paul Batt, Doug Spowart, Victoria Cooper, Gemma Avery, Michelle Powell, Mathias Heng and Christopher Köller.

Jackie Higgins and Max Kozloff’s 2014 The World Atlas of Street Photography (Yale University Press) features the work as an example of:

“A younger generation of photographers from Melbourne [who] have further expanded and complicated the street milieu. Ian Tippett’s work uses a particular, fragmentary vantage point of his young protagonists as an allegory in exploring the psychology of personal space and exhibitionism among the ‘selfie generation.’ His photographs pulse with color and energy, expounding and abstracting its subjects in the one breath with high flash. His ” Want You Back” series captures an intimate view of young revellers and their dazzling T-shirt prints, fashions, and abundance of bare skin.”

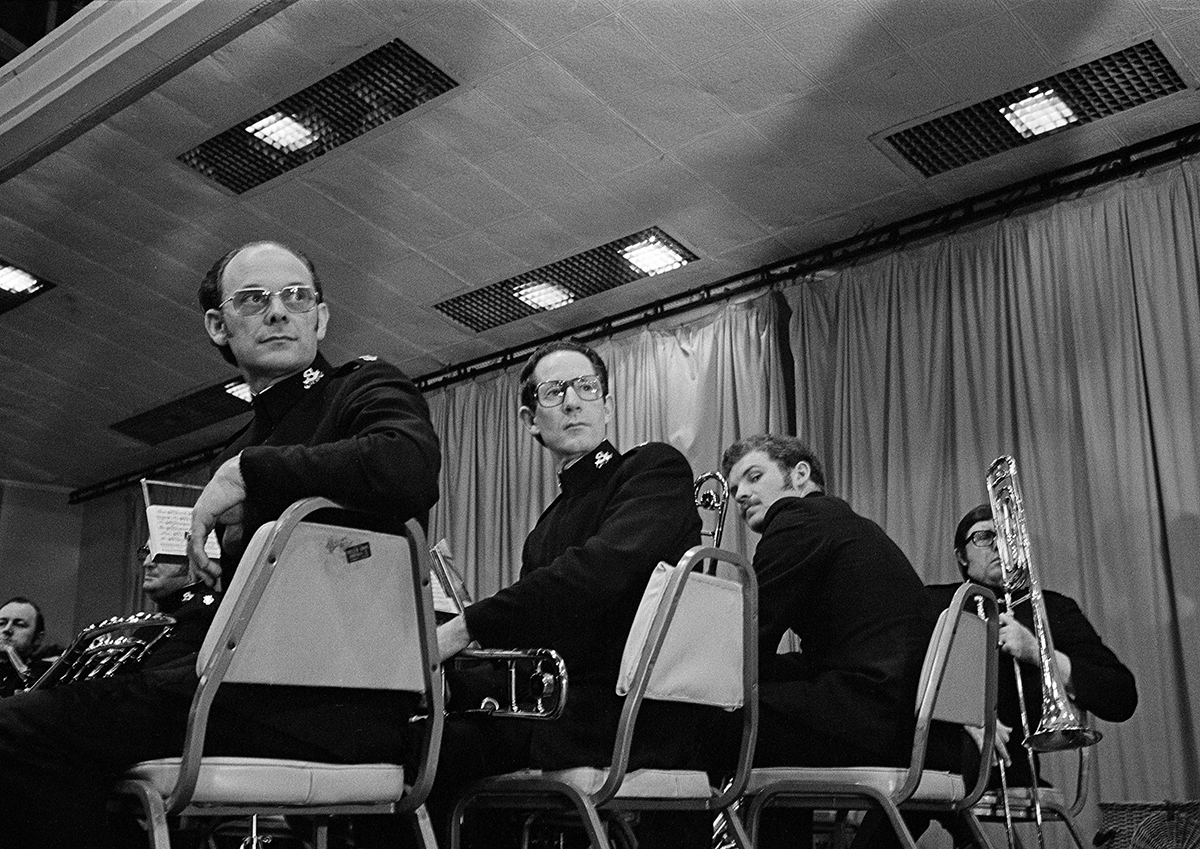

Looking back at Ian Tippett’s 1978 low-angle photograph of Salvation Army band members, it is clear how his humanist observation of the relationship of individuals with societal norms and forms, and his search for perceptive but detached angles of view, have advanced the street photograph so that it is still vibrantly relevant after the postmodern debunking of the ethics of the ‘objective’ documentary image.

Rainbow Jelly is a new project of work collected over a period of 10 years, up to 2020 which provides a glimpse of how Tippett’s ideas continue to progress:

Foootnotes

- Nichols, Bill. 1991. Representing Reality : Issues and Concepts in Documentary. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ↩︎

- Ennis, Helen. 2007. Photography and Australia. London: Reaktion Books, p.108 ↩︎

- Liz Cincotta ‘If You Do One Thing’ The Sunday Age 3 May 2005, Metro, p.6 ↩︎

- Jill Stowell ‘Feast for the eyes’ Newcastle Herald, 12 November 2005, p.14 ↩︎

- Tracey Clement ‘You’re a Loser, Baby’, Sydney Morning Herald, 17 March 2006, Metro p.23 ↩︎

- Robert McFarlane ‘Park life: poetic images from the city’s lost corner of dissent’ Sydney Morning Herald, 8 March 2006 p.16 ↩︎